We are supposedly living in an age of austerity, but many federal programs are leading many states into overspending and potential fiscal insolvency. Transit spending is a case in point, as is indicated by the proposed Orlando Sunrail commuter rail project.

How Washington Induces Higher State and Local Spending: For decades, the federal government has encouraged state and local governments to build expensive projects, as is the case in Orlando. Under the Federal Transit Administration (FTA) "New Starts" program, state and local governments can obtain federal funding for such projects, contingent on their taxpayers providing "matching funding." This can be in the form of higher taxes, budget increases or in unplanned subsequent expenditures that are higher than projected. The responsibility for cost overruns and operating subsidies belong exclusively to state or local taxpayers.

Inaccurate Cost Forecasts: This can prove very expensive. European researchers Bent Flyvbjerg, Nils Bruzelius and Werner Rottengather (Megaprojects and Risk: An Anatomy of Ambition) and others have shown that new rail projects routinely cost more than planned (Note 1).

Flyvbjerg et al found that the average rail project cost 45 more than projected and that 80 percent cost overruns were not unusual. Cost overruns were found to occur in 9 of 10 projects. Moreover, they found that despite increased attention to these cost blow-outs, final costs continue to be far above the projections presented to public officials and the taxpayers at approval time. Further, they found that ridership and passenger fares also often fell short of projections, increasing the need for operating subsidies.

Moreover, urban rail systems are of questionable value. Transport economist Clifford Winston of the Brookings Institution has noted that "the cost of building rail systems are notorious for exceeding expectations, while ridership levels tend to be much lower than anticipated" and that "continuing capital investments are swelling the deficit."

Federal policies, however, often force state and local taxpayers to guarantee the accuracy of notoriously inaccurate cost projections. The standard FTA "full funding agreement," a prerequisite for federal funding, requires state or local taxpayers to pay for any cost overruns. Further, if the projects are not completed, state and local taxpayers are required to pay back the federal grants (more on Florida’s experience with that later).

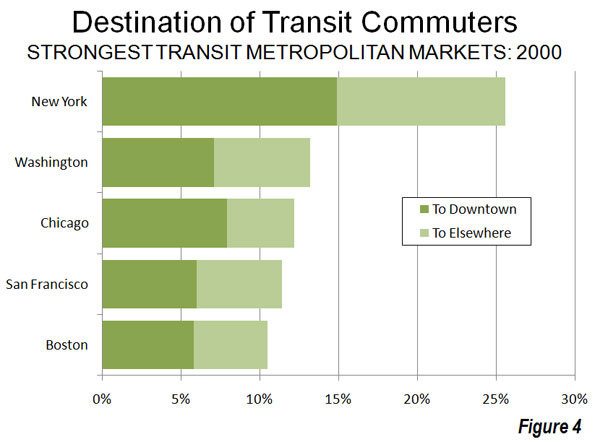

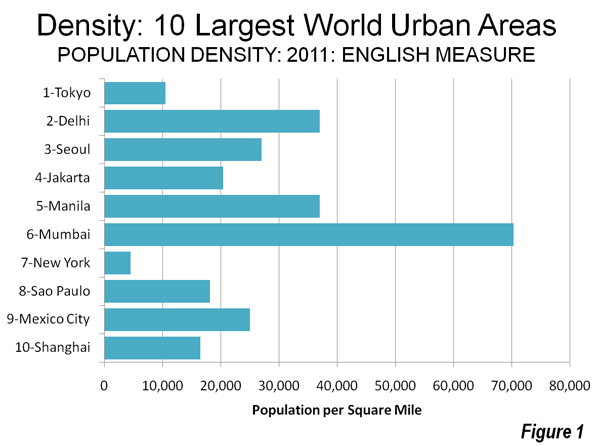

Sunrail: The "Sunrail" commuter rail project is planned to parallel Interstate 4 in the Orlando metropolitan area. From the perspective of Florida taxpayers, the tragedy is that the project has proceeded so far. Project forecasts say that in 2030, Sunrail will add only 1,850 new round trip riders daily to Orlando’s already sparse transit ridership (barely half a percent of travel). Even if all Sunrail trips were for employment, it would not even be a "drop in the bucket" in a metropolitan area likely to add more than 400,000 jobs by 2030. Further, despite inferences to the contrary, this will have less than negligible impact on traffic congestion. It is likely that traffic on Interstate 4 will increase by at least 100,000 cars daily by 2030 (Note 3), many times the cars that Sunrail could possibly remove, even under its probably exaggerated ridership projections.

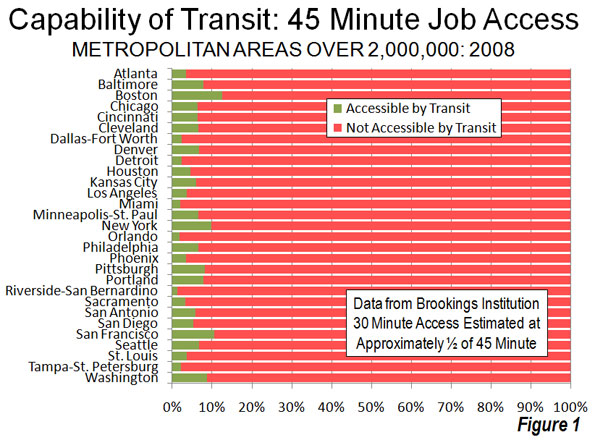

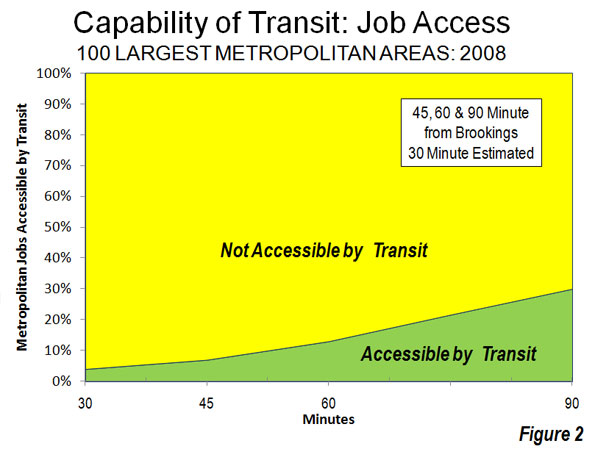

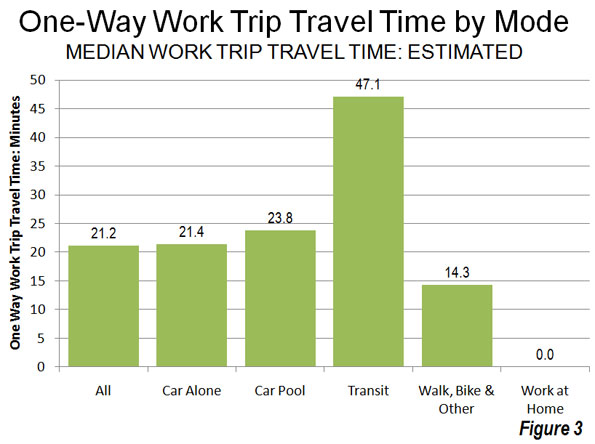

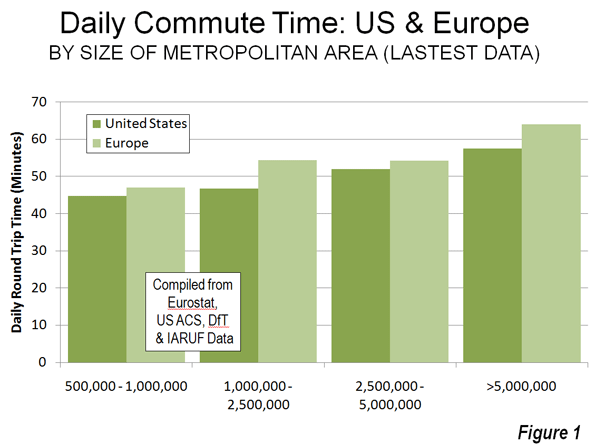

Sunrail also will do little to increase job access to jobs in a metropolitan area where less than two percent of employment can be reached by the average commuter in 45 minutes using transit, according to Brookings Institution research. By contrast, at least more than 80 percent of jobs in the Orlando metropolitan area are reached in 45 minutes by car, and more than 55 percent in 30 minutes. Despite the high costs of all this and Sunrail’s negligible effect on regional mobility, politics may preclude cancellation of the project.

Sunrail’s first phase is projected to cost $350 million (after a half-billion dollar right-of-way purchase). The Federal Transit Administration intends to pay a maximum of $175 million for the project. State taxpayers (through the Florida Department of Transportation) will be required to match that funding with another $175 million, though that amount could grow.

Florida Taxpayers Already Burnt Once: In addition in paying for likely Sunrail cost overruns, Florida taxpayers would be obligated to fund service levels that satisfy the Federal Transit Administration. Otherwise the federal government can demand that taxpayers send the money back. This is no idle threat. When the Miami commuter rail system (Tri-Rail) provided service levels deemed insufficient, FTA demanded a return of $250 million in federal grants. This repayment was averted only by a state bailout that provided up to $15 million in annual subsidies to increase the service levels (Note 2).

Essentially then, to obtain federal funding for Sunrail, Florida taxpayers must write a blank check out to a rail construction industry that has repeatedly demonstrated an inability to build rail projects for promised amounts.

Negotiating a Way Out? Florida taxpayers, however, may have some options to avoid writing the blank check. In March, the US Department of Transportation (USDOT) desperately sought to find governments in Florida willing to provide a blank check to fund the now cancelled Tampa to Orlando high-speed rail line, with costs that were so low that they had "big cost overruns" written all over them.

In a February 27 letter USDOT told local officials the federal grant repayment provisions were negotiable. Based upon this policy latitude available to USDOT, Florida officials could seek less unreasonable terms with USDOT. For example, a revision might be negotiated to limit Florida’s cost overrun liability to amounts resulting from state actions. Further, Florida should seek agreement that it does not have to operate service levels that are greater than required by demand or can be afforded. This would prevent a repeat of the unhappy Tri-Rail experience.

Provisions such as these would provide important protections to Florida taxpayers, who could otherwise be forced to pay hundreds of millions in cost overruns and higher operating subsidies and potentially higher taxes.

Lessons for Taxpayers: Projects like Orlando’s Sunrail provide important lessons for the nation. The stimulus, now winding down, boosted questionable spending policies well outside the Beltway. Washington needs to stop writing blank checks on taxpayer accounts. It’s time for the feds to stop inducing state and local governments to mimic its fiscal irresponsibility.

—–

Notes

1. Flyvbjerg is a professor at Oxford University in the United Kingdom. Bruzelius is an associate professor at the University of Stockholm. Rothengatter is head of the Institute of Economic Policy and Research at the University of Karlsruhe in Germany and has served as president of the World Conference on Transport Research Society (WCTRS), which is perhaps the largest and most prestigious international association of transport academics and professionals.

2. The Florida Department of Transportation has made agreements local governments to participate in funding of Sunrail cost overruns. However, in the event that local governments are unable to pay their share, it may be expected that the state will pay, as it did in bailing out Miami’s Tri-Rail (discussed above).

3. Assumes that automobile traffic would grow at the projected population growth rate (based upon University of Florida population projections).

—–

Wendell Cox is a Visiting Professor, Conservatoire National des Arts et Metiers, Paris and the author of “War on the Dream: How Anti-Sprawl Policy Threatens the Quality of Life”

Photo: Downtown Orlando (by author)