Access for residents to employment is critical to boosting city productivity. This has been demonstrated by researchers such as Remy Prud’homme and Chang-Woon Lee of the University of Paris, David Hartgen and M. Gregory Fields of the University of North Carolina, Charlotte. Generally, city productivity (economic growth and job creation) can be expected to improve more where employment access is better . Access is measured in the number of jobs that can be reached by the average employee in a certain period of time, like 30 minutes.

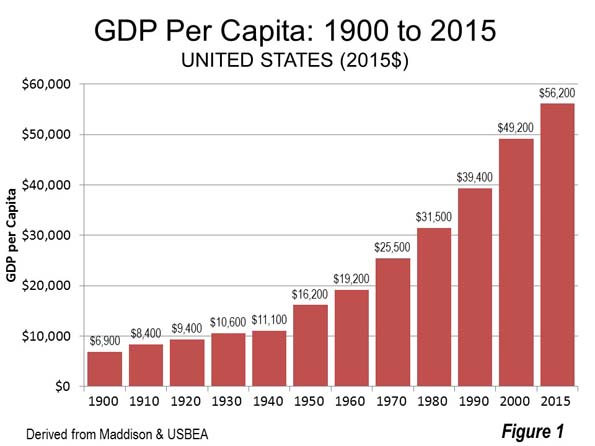

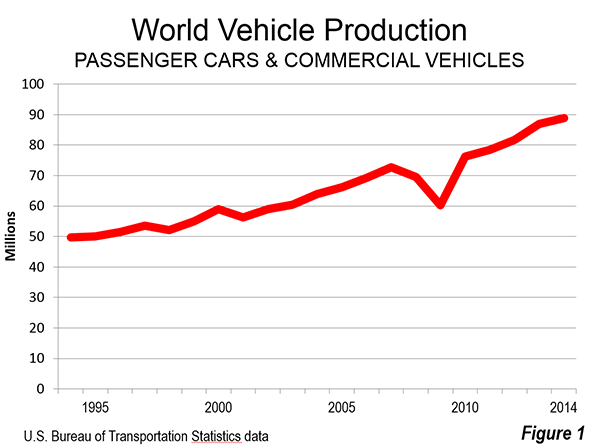

Generally, US cities have seen strong productivity gains as they have become more accessible. In 1900, before the broad adoption of the automobile, US gross domestic product (GDP) per capita was $6,900 (2015 dollars). By 1930, when there were 90 percent as many motor vehicles as households in the nation, GDP per capita rose to $10,600. Now, even factoring in the economic reverses of the last decade, GDP per capita is more than five times that amount (Figure 1).

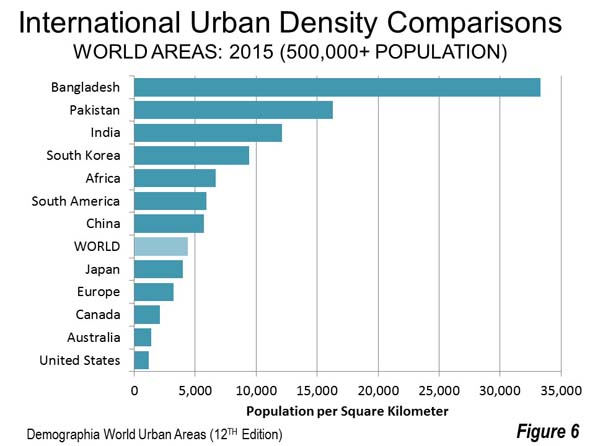

Further, American metropolitan areas tend to have shorter work trip travel times and less traffic congestion than their counterparts elsewhere. Much of this is due to their more decentralized employment bases than elsewhere in the world, where decentralization has increased at a slower rate.

Public officials and planners now have been given an important new tool for assessing access and improving metropolitan transportation. Researchers at the University of Minnesota Accessibility Laboratory have been studying accessibility in US employment markets (metropolitan areas) in the most detailed terms yet. The first report, in 2013, was authored by Professor David Levinson (on autos) and since that time Andrew Owen and Brendan Murphy have collaborated with Levinson in reports on autos, transit and walking. These modal reports measures access by the number of jobs that can be reached in a metropolitan area by the average employee in 10 minute intervals (from 10 to 60 minutes).

This article summarizes access in the 30 and 60 minute travel times in 49 metropolitan areas (Note 1). The 30 minute trip is used because it is close to the average one-way work trip travel time in the United States (26.4 minutes in 2015). The 60 minute trip is used is the longest commute considered. This “one hour economic circle” has also been adopted in Chinese cities, such as Chongqing for urban area planning, as recommended by former World Bank principal planner Alain Bertaud.

Access by Automobile

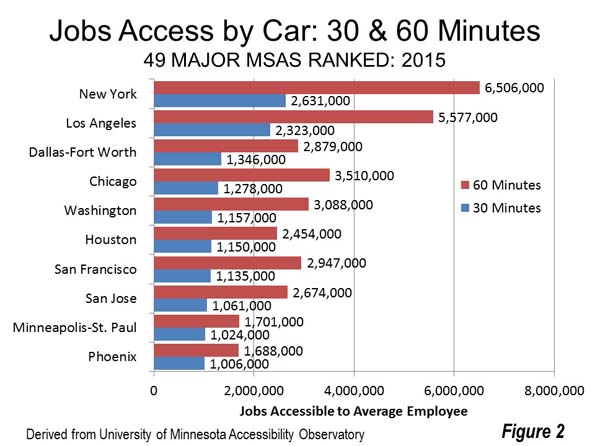

As one would expect, more jobs can be accessed in the larger metropolitan areas. New York leads, with 2.6 million jobs accessible to the average employee within 30 minutes by auto. New York is closely followed by Los Angeles, only 12 percent lower at 2.3 million. With a population 35 percent below that of New York, and with the worst traffic congestion in the United States, this is a surprising result. The greater dispersion of jobs in Los Angeles certainly helps. In third position, Dallas-Fort Worth surprisingly edges out much larger Chicago, in fourth position. This undoubtedly is the result of DFW’s superior freeway system, which along with its arterial system has resulted in the best traffic congestion in the world for any metropolitan area over 5 million population. Washington (Note 2) and Houston rank fifth and sixth.

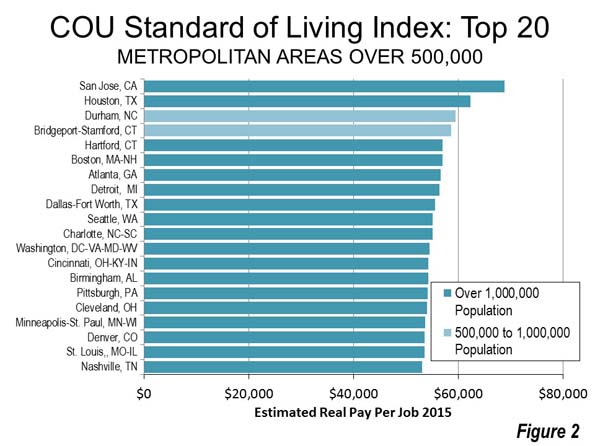

Employment access by autos in 60 minutes is the highest in New York, and Los Angeles, with Chicago third (ahead of Dallas-Fort Worth), probably due to its larger overall labor market (42 percent more jobs than Dallas-Fort Worth). Washington, San Francisco and Dallas-Fort Worth have around 3,000,000 auto accessible jobs (Figure 2).

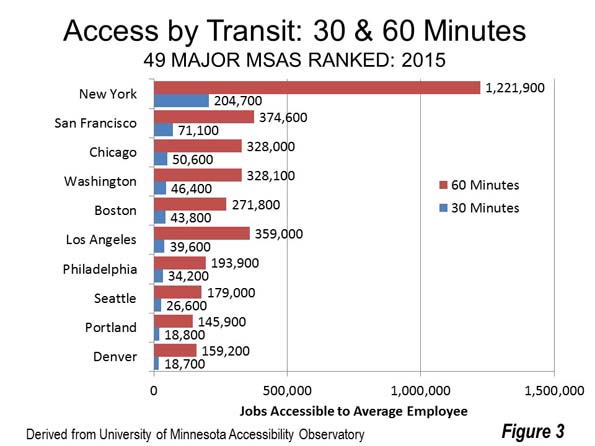

Access by Transit

Transit access is dominated by New York’s 200,000 jobs within 30 minutes access by transit. This is nearly three times that of second place San Francisco. The top five include three of the other metropolitan areas with the largest central business district (CBD or downtown) areas, Chicago, Washington and Boston, while Philadelphia, with the sixth largest CBD ranks seventh. Los Angeles ranks sixth. Seattle, Portland and Denver round out the top ten, well above their 15th, 24th and 21st population ranks. These high rankings may be a measure of their transit system quality, though access by transit is a mere fraction of their auto access.

New York leads in 60 minute transit access, at more than 1.2 million, followed by Los Angeles, San Francisco, Washington and Chicago (Figure 3).

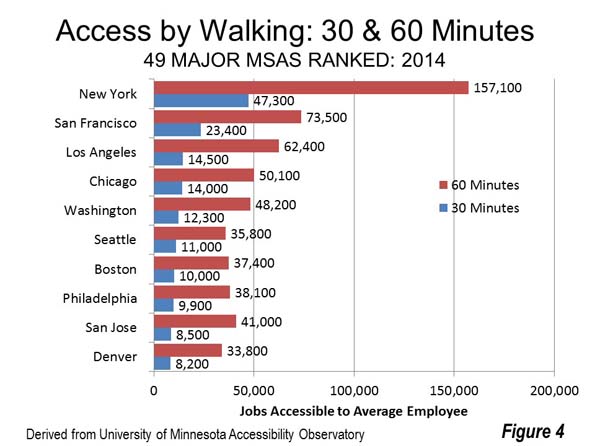

Access by Walking

New York also leads in 30 minute walk access, more than doubling that of second place San Francisco, at 47,300, followed by Los Angeles, Chicago and Washington. New York also leads in 60 minute walking access, at 157,100, followed, again, by San Francisco, Los Angeles, Chicago and Washington (Figure 4).

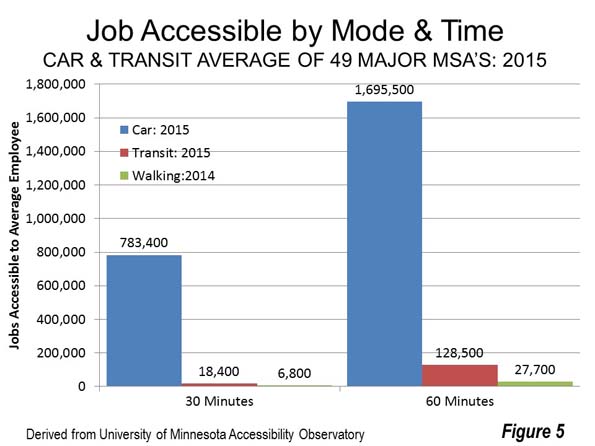

Modal Comparisons

The job accessibility differences between autos and transit are significant. On average among the 49 metropolitan areas, 30 minute access by car is 783,000 jobs, compared to only 18,000 for transit and 7,000 by walking. At 60 minutes, autos reach nearly 1.7 million jobs, compared to fewer than 130,000 for transit and 28,000 by walking. Thus, at 30 minutes, the accessible auto market is 43 times that of transit and 115 times that of walking (Figure 5).

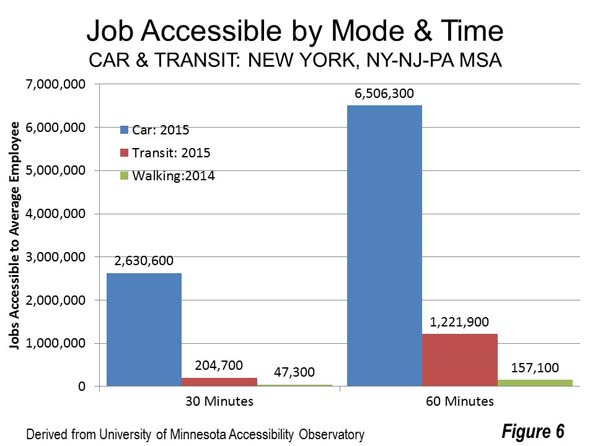

The ultimate transit city in the United States is New York. There, the average employee can reach 2.6 million jobs by auto in 30 minutes, compared to 205,000 for transit and 157,000 by walking. Auto access in 30 minutes is 13 times that of transit and 56 times that of walking (Figure 6).

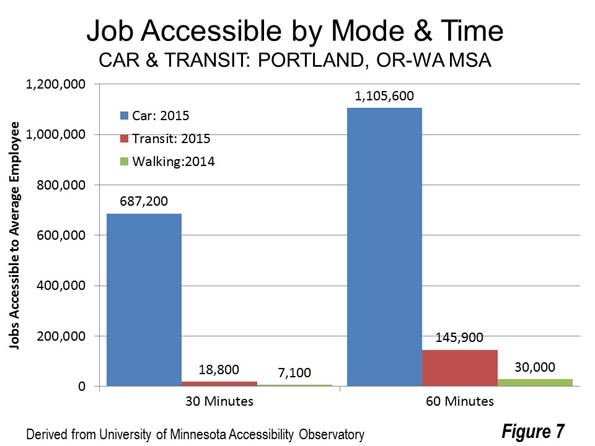

Portland is a metropolitan area often cited for its urban transport policies, especially its extensive light rail system. Further Portland has a comparatively strong, traditional central business district (downtown) and has implemented policies intended to reduce car use and encourage transit and walking as well as increase urban densities. The average Portlander can reach 687,000 jobs in 30 minutes by car, 19,000 by transit and only 7,000 by walking. That’s only slightly better than the national average, with autos providing 37 times the access of transit and 97 times that of walking (Figure 7).

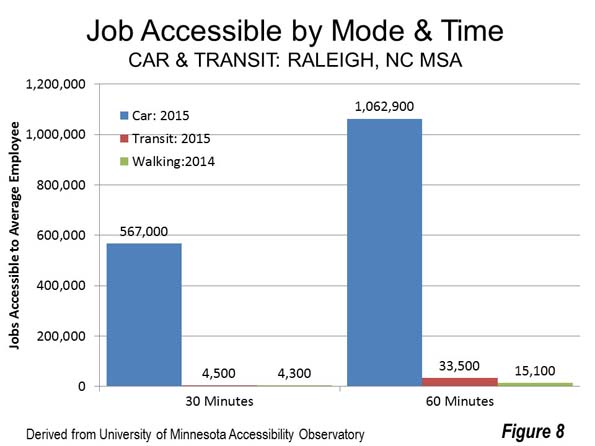

Raleigh (Note 2) is certainly not a new city, but its explosive growth has given the metropolitan area a post-World War II urban form, with comparatively low density (one-half that of Portland) and very low transit ridership. The average employee in Raleigh can reach 567,000 jobs by car in 30 minutes, compared to 4,500 by transit and 4,300 by walking. Raleigh’s auto access is 125 times that of transit and 132 times that of walking, both higher than the national average (Figure 8).

Extending Auto Mobility to All

It is clear from the data that access to an auto provides unique advantages in comparison to transit or walking. Professor Robert Gordon, in his seminal The Rise and Fall of American Growth says that" "Much of the enthusiastic transition away from urban mass transit to automobiles reflected the inherent flexibility of the internal combustion engine—it could take you directly from your origin point to your destination with no need to walk to a streetcar stop, board a streetcar, often change to another streetcar line (which required more waiting), and then walk to your final destination."

It might be asked, “how can it be that this is so in view of the many billions spent on new urban rail lines?” The answer is that transit cannot be competitive with the automobile in the modern urban area. Professor Jean-Claude Ziv and I concluded that it could take all of an urban area’s gross domestic product each year to build and operate such a system.

At the same time, transit moves a large share commuters to the largest central business districts in the transit legacy cities. This is an important niche market, but not a large percentage overall.

With the practical impossibility of replicating auto mobility for people who cannot afford cars, new thinking is needed. One approach could be auto ownership programs, according to Evelyn Bloomenberg and Margy Waller in a 2003 Brookings Institution paper. This could require shifting transit funding priorities toward employment access and the longer term economic growth that would produce.

Note 1: The latest reports cover 50 metropolitan areas. This article deals with 49, because no transit data was provided for Memphis.

Note 2: Some metropolitan areas are virtually adjacent to others. This can increase the jobs accessible because there is significant employment outside the metropolitan area, in an adjacent metropolitan area. Examples are San Francisco and San Jose, Washington and Baltimore, and Raleigh and Durham.

Photo: Suburban Employment Center: Chicago (by author)

Wendell Cox is principal of Demographia, an international public policy and demographics firm. He is a Senior Fellow of the Center for Opportunity Urbanism (US), Senior Fellow for Housing Affordability and Municipal Policy for the Frontier Centre for Public Policy (Canada), and a member of the Board of Advisors of the Center for Demographics and Policy at Chapman University (California). He is co-author of the "Demographia International Housing Affordability Survey" and author of "Demographia World Urban Areas" and "War on the Dream: How Anti-Sprawl Policy Threatens the Quality of Life." He was appointed to three terms on the Los Angeles County Transportation Commission, where he served with the leading city and county leadership as the only non-elected member. He served as a visiting professor at the Conservatoire National des Arts et Metiers, a national university in Paris.

Photo: Zhou En Lai’s Buick, Zhou En Lai Museum, Nanjing

Photo: Zhou En Lai’s Buick, Zhou En Lai Museum, Nanjing Photo: G4 Expressway between Zhengzhou, Henan and Wuhan, Hubei

Photo: G4 Expressway between Zhengzhou, Henan and Wuhan, Hubei

Photo: Ford F-150 (2017 model)

Photo: Ford F-150 (2017 model)