The idea of “smart growth” should be like mom and apple pie. But take a closer look and you find, for the most part, that smart growth policies often have unintended consequences that are anything but smart.

If housing is unaffordable, the cost of living is high and people are leaving, it probably means that a state rates higher in smart growth policies. That’s the story from an analysis of the new Smart Growth America state ratings on transportation policies the organization believes would reduce greenhouse gas emissions. The new ratings are based upon strategies recommended in Moving Cooler, a smart growth oriented report authored by Cambridge Systematics in 2009 (Note 1).

The new Smart Growth America ratings and the Moving Cooler strategies relied, in large measure, on strategies that would force higher population densities, virtually stop development on and beyond the urban fringe, and seek to, in the immortal words of Transportation Secretary Ray Lahood, “coerce” people out of cars.

Yet when the new ratings are arrayed alongside measures of the quality of life, such as housing affordability and the cost of living, smart growth shows its less attractive side. You can see this, for example, in patterns of domestic migration states with the highest Smart Growth America scores also suffer the highest net domestic out-migration. .

Quality of Life Indicators: The following analysis compares the Smart Growth America ratings of the states with quality of life indicators, which include lower house prices, a lower cost of living and a greater net domestic migration (Note 2).

- Housing Affordability: Housing affordability is measured using a median value multiple (Note 3), which is the median house value by the median household income (from the 2009 American Community Survey). Economic research generally indicates that smart growth land use policies lead to higher house prices and lower levels of housing affordability. A lower housing affordability score means that housing is more affordable, and is an indication of a better quality of life. Generally, the median value multiple was 3.0 or below until the housing bubble and remains at that level in some states.

- Cost of Living: The overall cost of living was examined using regional price parities developed by the Bureau of Economic Analysis (US Department of Commerce) in the form of “regional price parities.” Regional price parities are the domestic equivalent of “purchasing power parities,” which are used to adjust personal income and gross domestic product data between nations. A lower score means that the cost of living is lower and is an indication of a better quality of life.

- Net Domestic Migration: Net domestic migration rates are for the period of 2000 to 2009 and based upon Bureau of the Census data and is calculated as a percentage of the 2000 population. A higher score means that more people are moving in than moving out. A state with a higher score is more attractive to movers than states with lower scores, which is also an indication of a better quality of life.

The Top (Mostly Bottom) Ten

Generally, the states with the highest Smart Growth America ratings perform the worst by these quality of life indicators.

California is first in Smart Growth America score, at 82 (out of a possible 100). Yet, California ranks 49th in housing affordability, 48th in cost of living and 45th in net domestic migration, having lost 4.4 percent of its population (1.5 million) to other states since 2009. California’s average rank among the quality of life indicators is 47, essentially a mirror image of its Smart Growth America rating. Only New York has a worse average ranking (49th).

Maryland is second in Smart Growth America score, at 77. However, Maryland ranks 42nd in housing affordability, 41st in the cost of living and 36th in net domestic migration, having lost 1.8 percent of its residents (nearly 100,000) to other states since 2000. Maryland’s average rank is 40th on the quality of life indicators.

New Jersey ranks third, with a Smart Growth America score of 75. New Jersey ranks 45th in housing affordability, 47th in the cost of living and 47th in domestic migration, having lost 4.5 percent of its population (450,000) to other states during the decade. Among the top ten, only California has a worse average ranking than New Jersey’s, at 46th on the quality of life indicators.

Connecticut ranks fourth, with a Smart Growth America score of 70. Connecticut ranks 40th in housing affordability, 46th in cost of living and 40th in domestic migration, having lost 2.8 percent (nearly 100,000) of its population. Connecticut’s average rank is 42th in the quality of life indicators.

Washington is fifth in Smart Growth America score, at 68. Washington ranks 44th in housing affordability and 40th in cost of living. Washington ranked much higher, however, in domestic migration at 14th, with a gain of 4.0 percent (240,000). Washington, like other western states, has been the recipient of strong migration from even more expensive coastal California. Washington’s average rank is 33rd in the quality of life indicators.

Oregon ranks sixth, with a Smart Growth America score of 65. The state ranks 47th in housing affordability (trailing Hawaii, California and New York), but has a higher average cost of living ranking (31st) and in domestic migration, principally because it, like Washington is a favored destination by people fleeing California.

Seventh ranked Massachusetts (64) scores much more consistently in the quality of life indicators, at 46th in housing affordability, 45th in the cost of living, 44th in net domestic migration and 45th overall.

Neighboring Rhode Island (61) ranks eighth and is also a consistent performer, ranking 43rd in housing affordability and net domestic migration, 44th in the cost of living and 43rd overall.

Delaware and Minnesota share 9th place with a Smart Growth America score of 59. Delaware’s average ranking is 28th, and Minnesota’s average ranking is 29th. Delaware’s ranking, near the top of the bottom 25 is driven by a high net domestic migration rate. Minnesota scores similarly in all quality of life indicators.

Two states scoring the worst in the quality of life indicators were notably absent in the Top (Mostly Bottom) Ten. New York’s average rank was 49, compared to its Smart Growth America rank of 21. Hawaii’s average quality of life indicator rank was 46 and its Smart Growth America rank was 15. Some of the worst housing affordability and highest costs of living drove their low quality of life scores.

States with Higher Quality of life Indicators

The five states with the lowest Smart Growth America scores are Nebraska, North Dakota, West Virginia, Mississippi and Arkansas. These states surely qualify as “flyover” country, being well removed from the more elite coasts. Yet, each of these states scores considerably better than Smart Growth America’s top ten states, with some of the nation’s best housing affordability and lowest costs of living. Slightly more people moved out of these states than moved in. However, bottom ranked Arkansas (Smart Growth America score of 2) attracted 75,000 net domestic residents, almost 1.6 million more than Smart Growth America’s top ranked California and 170,000 more than second ranked Maryland.

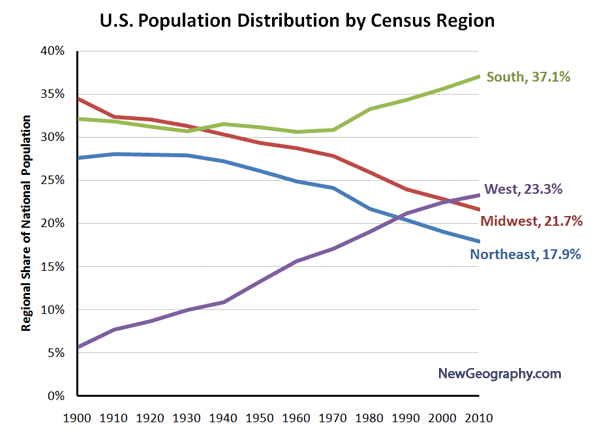

Texas (15th), North Carolina (16th) and Georgia (17th) were among the higher scoring large states in the quality of life indicators. The high Texas ranking resulted from higher rankings in housing affordability and net domestic migration. Georgia and North Carolina had among the highest rankings in net domestic migration.

Statistical Analyses

For fun, I did a quick statistical analysis, which indicated that inferior housing affordability and a higher cost of living are associated with a higher Smart Growth America score, at a 99 percent level of confidence (Note 4).

This relationship is evident in Table 1, which is a summary by Smart Growth America scores. Housing affordability and the cost of living all improve as the Smart Growth America score declines. At this level, a similar relationship is evident in the net domestic migration rate, with the exception of states with a Smart Growth America score of under 20. The states with the highest Smart Growth America ratings (60 and over) lost 2.5 million domestic migrants, while the states with scores from 40 to 60 lost 500,000. States with Smart Growth America ratings under 40 gained 2.5 million domestic migrants, more people than live in all of the nation’s municipalities except for New York, Los Angeles and Chicago. Table 2 provides detailed data for all states.

| Table 1 |

|

|

|

|

| Quality of Life Indicator Summary by Smart Growth Score |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Smart Growth America Score |

Housing Affordability

|

Cost of Living

|

Net Domestic Migration Rate

|

Net Domestic Migration

|

| 60 & Over |

5.1

|

114.5

|

-1.7%

|

(2,035,132)

|

| 40 to 60 |

4.3

|

102.2

|

1.8%

|

(501,121)

|

| 20 to 40 |

3.3

|

87.7

|

2.2%

|

2,576,584

|

| Under 20 |

2.6

|

79.2

|

-0.5%

|

(517)

|

| Table 2 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Smart Growth America Transportation Ratings & Quality of Life Indicator Summary by State |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Smart Growth America Rating

|

Quality of Life Indicators

|

| State |

Housing Affordability

|

Cost of Living

|

Net Domestic Migration Rate

|

Average Rank

|

|

Value

|

Rank

|

Value

|

Rank

|

Value

|

Rank

|

Value

|

Rank

|

| California |

82

|

1

|

6.5

|

49

|

129.1

|

48

|

-4.4%

|

45

|

47

|

| Maryland |

77

|

2

|

4.6

|

42

|

106.5

|

41

|

-1.8%

|

36

|

40

|

| New Jersey |

75

|

3

|

5.1

|

45

|

125.6

|

47

|

-5.4%

|

47

|

46

|

| Connecticut |

70

|

4

|

4.3

|

40

|

121.6

|

46

|

-2.8%

|

40

|

42

|

| Washington |

68

|

5

|

5.1

|

44

|

102.9

|

40

|

4.0%

|

14

|

33

|

| Oregon |

65

|

6

|

5.3

|

47

|

95.4

|

31

|

5.2%

|

9

|

29

|

| Massachusetts |

64

|

7

|

5.3

|

46

|

120.8

|

45

|

-4.3%

|

44

|

45

|

| Rhode Island |

61

|

8

|

4.9

|

43

|

113.7

|

44

|

-4.3%

|

43

|

43

|

| Delaware |

59

|

9

|

4.4

|

41

|

97.7

|

34

|

5.8%

|

8

|

28

|

| Minnesota |

59

|

9

|

3.6

|

26

|

92.6

|

28

|

-0.9%

|

32

|

29

|

| Vermont |

57

|

11

|

4.2

|

37

|

99.5

|

36

|

-0.2%

|

29

|

34

|

| Illinois |

53

|

12

|

3.7

|

28

|

99.2

|

35

|

-4.9%

|

46

|

36

|

| Virginia |

51

|

13

|

4.3

|

38

|

102.1

|

39

|

2.3%

|

19

|

32

|

| Wisconsin |

51

|

13

|

3.4

|

21

|

91.5

|

24

|

-0.2%

|

28

|

24

|

| Hawaii |

50

|

15

|

8.1

|

50

|

133.4

|

50

|

-2.4%

|

38

|

46

|

| Pennsylvania |

50

|

15

|

3.3

|

20

|

94.2

|

29

|

-0.3%

|

30

|

26

|

| Arizona |

45

|

17

|

3.9

|

30

|

94.4

|

30

|

13.5%

|

2

|

21

|

| Florida |

45

|

17

|

4.1

|

34

|

99.9

|

37

|

7.2%

|

6

|

26

|

| Michigan |

45

|

17

|

2.9

|

12

|

92.5

|

27

|

-5.4%

|

48

|

29

|

| Nevada |

42

|

20

|

3.9

|

32

|

100.4

|

38

|

17.9%

|

1

|

24

|

| New York |

41

|

21

|

5.6

|

48

|

131.8

|

49

|

-8.7%

|

50

|

49

|

| New Mexico |

37

|

22

|

3.7

|

27

|

83.5

|

14

|

1.4%

|

23

|

21

|

| Colorado |

36

|

23

|

4.3

|

39

|

97.1

|

32

|

4.7%

|

10

|

27

|

| Utah |

36

|

23

|

4.1

|

33

|

86.5

|

19

|

2.4%

|

18

|

23

|

| Kentucky |

35

|

25

|

2.9

|

13

|

80.8

|

4

|

2.0%

|

21

|

13

|

| Tennessee |

35

|

25

|

3.3

|

19

|

84.7

|

18

|

4.6%

|

12

|

16

|

| Alaska |

34

|

27

|

3.5

|

23

|

106.7

|

42

|

-1.2%

|

33

|

33

|

| Maine |

33

|

28

|

3.9

|

31

|

92.2

|

26

|

2.3%

|

20

|

26

|

| South Carolina |

33

|

28

|

3.2

|

18

|

83.2

|

13

|

7.6%

|

5

|

12

|

| New Hampshire |

32

|

30

|

4.1

|

35

|

113

|

43

|

2.6%

|

17

|

32

|

| Georgia |

31

|

31

|

3.4

|

22

|

87.9

|

23

|

6.7%

|

7

|

17

|

| Kansas |

31

|

31

|

2.6

|

7

|

83.6

|

16

|

-2.5%

|

39

|

21

|

| Idaho |

30

|

33

|

3.8

|

29

|

82.7

|

10

|

8.5%

|

3

|

14

|

| Iowa |

28

|

34

|

2.5

|

3

|

82.9

|

11

|

-1.7%

|

35

|

16

|

| Ohio |

28

|

34

|

3.0

|

15

|

87.2

|

21

|

-3.2%

|

42

|

26

|

| Texas |

27

|

36

|

2.6

|

6

|

91.7

|

25

|

4.0%

|

15

|

15

|

| North Carolina |

26

|

37

|

3.6

|

25

|

86.9

|

20

|

8.2%

|

4

|

16

|

| Missouri |

25

|

38

|

3.1

|

16

|

81.3

|

7

|

0.7%

|

27

|

17

|

| Oklahoma |

24

|

39

|

2.6

|

4

|

81.6

|

8

|

1.2%

|

24

|

12

|

| Alabama |

23

|

40

|

3.0

|

14

|

80.8

|

4

|

2.0%

|

22

|

13

|

| Louisiana |

23

|

40

|

3.2

|

17

|

83.6

|

16

|

-7.0%

|

49

|

27

|

| Montana |

23

|

40

|

4.2

|

36

|

83.1

|

12

|

4.4%

|

13

|

20

|

| South Dakota |

23

|

40

|

2.8

|

11

|

82.3

|

9

|

1.0%

|

26

|

15

|

| Wyoming |

21

|

44

|

3.5

|

24

|

97.4

|

33

|

4.6%

|

11

|

23

|

| Indiana |

20

|

45

|

2.7

|

9

|

83.5

|

14

|

-0.4%

|

31

|

18

|

| Nebraska |

18

|

46

|

2.6

|

5

|

87.3

|

22

|

-2.3%

|

37

|

21

|

| North Dakota |

18

|

46

|

2.4

|

1

|

79.5

|

3

|

-2.8%

|

41

|

15

|

| West Virginia |

13

|

48

|

2.5

|

2

|

70.3

|

1

|

1.0%

|

25

|

9

|

| Mississippi |

12

|

49

|

2.7

|

8

|

80.8

|

4

|

-1.3%

|

34

|

15

|

| Arkansas |

2

|

50

|

2.7

|

10

|

78.2

|

2

|

2.8%

|

16

|

9

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Housing Affordability: Median House Value/Median Household Income, 2009 |

|

| Cost of Living: Regional Price Parities, 2006 |

|

|

|

|

|

| Net Domestic Migration: 2000-2009 Migration/2000 Population |

|

|

|

——————-

Note 1: Moving Cooler has been criticized by Alan Pisarksi (ULI Moving Cooler Report: Exaggerations and Misconceptions) and this author (Reducing Vehicle Miles Traveled Produces Meager Greenhouse Gas Emissions Returns) in previous newgeography.com articles.

Note 2: There are additional quality of life indicators, such as shorter work trip travel times, less intense traffic congestion, less intense air pollution, more living space, etc.

Note 3: This measure is based upon median house value, which is the only data available at the state level. The median value multiple is different from the Median Multiple (median house price divided by median household income), which is widely used in metropolitan area analysis (such as in the Demographia International Housing Affordability Survey).

Note 4: Details of the regression analysis: The dependent variable was the Smart Growth America score. The independent variables were the cost of living indicator and the domestic migration rate. The coefficient of determination (R2) was 0.55. (The positive relationship to the cost of living was strong, with a probability of only 1 in 10,000 that the result could have occurred by chance. The indicated association with the net migration rate was weak; the chance association cannot be ruled out).

Wendell Cox is a Visiting Professor, Conservatoire National des Arts et Metiers, Paris and the author of “War on the Dream: How Anti-Sprawl Policy Threatens the Quality of Life ”

”

A survey of 120,000 temporary migrant workers in urban areas working by the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences research center found that only 25 percent would be interested in trading their rural residency permits for urban residency permits. The survey covered working age adults in 106 prefectures with large urban areas.

A survey of 120,000 temporary migrant workers in urban areas working by the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences research center found that only 25 percent would be interested in trading their rural residency permits for urban residency permits. The survey covered working age adults in 106 prefectures with large urban areas.