Central Buenos Aires is undoubtedly one of the world’s great tourist destinations. Days could be spent walking among its narrow streets admiring the plentiful art noveau, art-deco, beaux-arts and other architectural styles. The triumphal Avenida 9 de Julio is one of the world’s widest boulevards with two interior roadways of up to seven lanes and two service roads of two lanes, with a Washington Monument type obelisk at Avenida Corrientes (Top photo). Avenida 9 de Julio is bordered by buildings that are both ordinary and impressive, such as the Colon Opera House.

There is also an attractive area of redevelopment adjacent to the core in the former dock area, Puerto Madero. The old port buildings have been converted to commercial uses, especially restaurants. A number of high-rise condominium buildings have been constructed beyond the old port basins. Government buildings more than match the commercial architecture, with the National Congress and the Casa Rosada, or “Pink House,” with its balconies from which President Peron and his wife Eva used to address the public (Photo 2). Not more than two weeks ago, former President Nestor Kirchner lay in state to be visited by in an emotional outpouring by hundreds of thousands of Argentineans. The city of Buenos Aires also has a distinctive legislative building (Photo 3).

These older romantic styles make Buenos Aires a wonderful walking environment. Most were erected in the first three decades of the 20th century. This was Buenos Aires at its zenith. Then, Buenos Aires was capital of one of the world’s acknowledged economic powers. Argentina generally ranked around10th in gross domestic product (GDP) per capita during that period (Note 1). Thus, today, the tourist can enjoy the product of that prosperous time.

Economic Stagnation: More recent years have not been good to the Buenos Aires area and Argentina. The nation has seen decades of ups and downs – but mostly downs. The nation has been buffeted between constitutional governments and military dictatorships. Too often, even the constitutional governments have placed too little emphasis on creating wealth and too much on redistributing it. A failed currency policy in the 1990s destroyed the savings of millions. All of this has led to Argentina’s migration from the top 10 economies to near the bottom of the top 100, now ranked at 82nd in the world in GDP per capita. No top ten nation from early in the 20th century has fallen so far. New Zealand managed to drop from 1st in the world in 1920 to 51st now, but still has a GDP per capita double that of Argentina.

Argentina suffered the largest sovereign debt default in world history, at $100 billion in 2002. The nation’s former colonial master, Spain, trailed Argentina in GDP per capita throughout the 20th century to the 1980s, yet is now more than twice as prosperous (Figure 1)

This economic decline is not so evident in the autonomous city of Buenos Aires, which is also called Capital Federal, analogous to the District of Columbia (DC) in the United States. This is the Buenos Aires of tourists, an area only slightly larger than Washington, DC, but with five times the population. The municipality of Buenos Aires is by far the most affluent urbanization in the nation. Even so, there are informal settlements within the city, such as Villa 31. Overall, approximately three percent of the city’s population is in these kinds of informal settlements.

BA3-bencich

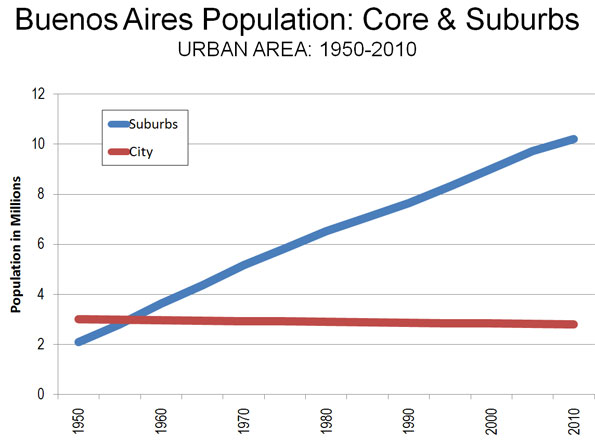

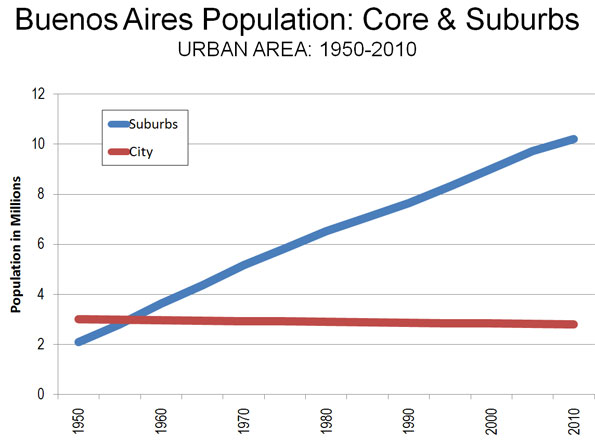

Population and Distribution: According to the last census (2001), the city of Buenos Aires had fewer people than in 1947, having fallen from 3.0 million residents to 2.8 million. The city is also very dense, at 35,600 persons per square mile (13,700 per square kilometer), which is about one-half the density of Manhattan or the ville de Paris and double the density of the city of San Francisco.

Population and Distribution: According to the last census (2001), the city of Buenos Aires had fewer people than in 1947, having fallen from 3.0 million residents to 2.8 million. The city is also very dense, at 35,600 persons per square mile (13,700 per square kilometer), which is about one-half the density of Manhattan or the ville de Paris and double the density of the city of San Francisco.

Most of the population lives in peripheral areas. This dominant suburban growth pattern is typical of world urbanization, as can be seen in such high-income nation capitals as London, Washington, Brussels, Copenhagen has been in the suburbs. Indeed, all growth in Paris has been in the suburbs since 1881. Like the ville de Paris, the city of Buenos Aires now accounts for less than 25 percent of its metropolitan area population (Figure 2).

Overall, the urban area (area of continuous development) has nearly 13 million people and covers more than 1,000 square miles (2,600 square kilometers) for a population density of 12,100 per square mile (4,700 per square kilometer). This is 70 percent more dense than Los Angeles and one-third more than Paris but less than one-eighth that of Dhaka (Bangladesh).

Suburban Buenos Aires: The suburbs of Buenos Aires differ from those in high-income national capitals. Generally, the suburbs are far poorer than the city and reflect the more recently less affluent Argentina that has emerged in recent decades just as the central area testified to the nation’s former relative wealth. All of suburban Buenos Aires is in the adjacent Buenos Aires province, which has the largest population in the nation.

Some of the suburbs are affluent, especially to the northwest, where suburban municipalities like Pilar and Tigre contain housing that could easily fit in upper middle income suburbs of the United States or Europe. However, even in these areas, there are close-by developments of low-quality and even informal housing, mostly housing domestic employees to the higher income population.

The suburban poverty is far more pervasive to the southwest and the southeast. Many neighborhoods look similar to modest suburbs in Mexico City, though without the pervasive informal settlements. More people live in informal settlements in the suburbs than in the city, with estimates putting the number at above 500,000.

The suburban poverty is far more pervasive to the southwest and the southeast. Many neighborhoods look similar to modest suburbs in Mexico City, though without the pervasive informal settlements. More people live in informal settlements in the suburbs than in the city, with estimates putting the number at above 500,000.

More than the Core: Any thought, however, of Buenos Aires being a “compact city” is dispelled by the vast sea of lights visible on an evening flight out of Ezeiza International Airport. The urbanization stretches 30 to 40 miles in all possible directions, to the northwest, southwest and southeast (with the Rio de la Plata being to the northeast).

However, probably no urban area illustrates the general rule that urban cores tend to be substantially different from their suburbs. Not only is suburban Buenos Aires far less dense, but it is far less affluent. Any who visits the city alone will have missed more than three-quarters of the reality.

————

Note: GDP per Capita data based upon Angus Maddison’s work for the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development.

Photos (by the author):

Top: Avenida 9 de Julio

2: Casa Rosada

3: City of Buenos Aires Legislative & Office Buildings

4: Bencich Building

5: Casa Borolo

————

Wendell Cox is a Visiting Professor, Conservatoire National des Arts et Metiers, Paris and the author of “War on the Dream: How Anti-Sprawl Policy Threatens the Quality of Life ”

”

Population and Distribution: According to the last census (2001), the city of Buenos Aires had fewer people than in 1947,

Population and Distribution: According to the last census (2001), the city of Buenos Aires had fewer people than in 1947,

The suburban poverty is far more pervasive to the southwest and the southeast. Many neighborhoods look similar to modest suburbs in Mexico City, though without the pervasive informal settlements. More people live in informal settlements in the suburbs than in the city, with estimates putting the number at above 500,000.

The suburban poverty is far more pervasive to the southwest and the southeast. Many neighborhoods look similar to modest suburbs in Mexico City, though without the pervasive informal settlements. More people live in informal settlements in the suburbs than in the city, with estimates putting the number at above 500,000.

Locating new satellite towns far enough to make commuting infeasible will be a real problem for Beijing. There just is not enough territory in the provincial level municipality. That means the new towns would have to be in the province Hebei, which along with the province level municipality of Tianjin surrounds Beijing.

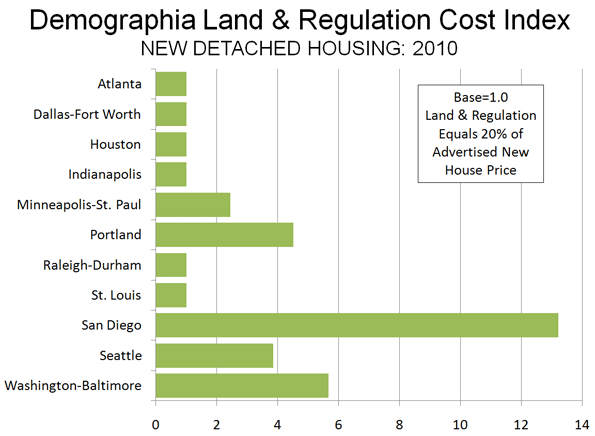

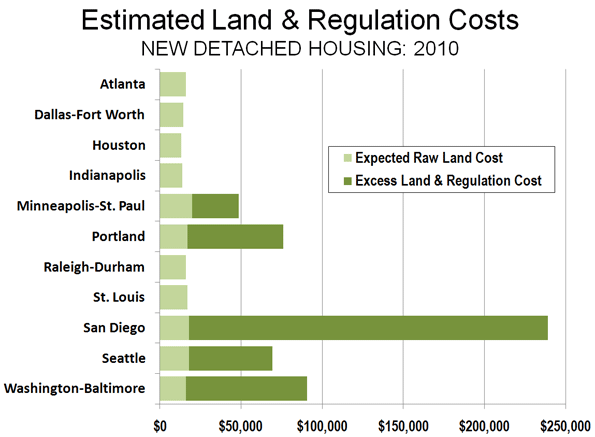

Locating new satellite towns far enough to make commuting infeasible will be a real problem for Beijing. There just is not enough territory in the provincial level municipality. That means the new towns would have to be in the province Hebei, which along with the province level municipality of Tianjin surrounds Beijing. Recently (February), I examined tax assessment records for all parcels in Portland’s Washington County that abut the urban growth boundary to see if value differences exist. The properties had to be 5 or more acres and be undeveloped. Research was conducted based upon Internet information in February 2010. Property along 25 miles of the urban growth boundary from Cedar Hills to Hillsboro to southwest Beaverton was included in the analysis.

Recently (February), I examined tax assessment records for all parcels in Portland’s Washington County that abut the urban growth boundary to see if value differences exist. The properties had to be 5 or more acres and be undeveloped. Research was conducted based upon Internet information in February 2010. Property along 25 miles of the urban growth boundary from Cedar Hills to Hillsboro to southwest Beaverton was included in the analysis.