Few books in recent memory have started from as optimistic or solid a foundation as Reinventing the Automobile: Personal Urban Mobility for the 21st Century. Reinventing the Automobile conveys a strong message that improved personal mobility is necessary and desirable:

“Have we reached the point where we now must seriously consider trading off the personal mobility and economic prosperity enabled by automobile transportation to mitigate its negative side effects? Or, can we take advantage of converging 21st century technologies and fresh design approaches to diminish those side effects sufficiently while preserving and enhancing our freedom to move about and interact? This book concludes the latter.”

The authors include William J. Mitchell, Professor of Architecture, and Media Arts and Sciences at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology directs the Smart Cities research group at the MIT Media Lab, Christopher Boroni-Bird, Director of Advance technology Vehicle Concepts at General Motors and Lawrence D. Burns, who consults on transportation, energy and communications systems and technology. The book is published by the MIT Press.

Getting Urban Economics Right

The authors start with getting the urban economics right. They recognize that the “freedom and prosperity benefits” of the automobile “have been substantial.” They note that the automobile industry “set the stage for the growth of the middle class,” something that has been labeled the “democratization of prosperity.” The authors say that the car “enabled modern suburbia” and “powered a century of economic prosperity.” This refreshing treatment is consistent with the overwhelming economic evidence that links personal mobility with prosperity, such as by Remy Prud’homme and Chang-Wong Lee, David Hartgen and M. Gregory Fields and others. It is also at considerable odds with the widely accepted, somewhat nostalgic planning orthodoxy that rejects private automotive transport as “unsustainable”, unaesthetic and anti-social. This ideology embraces the illusion that forcing people to travel longer, with less personal flexibility somehow will improve the economy and raise the standard of living.

The Future of the Automobile?

The authors envision a automobile characterized by a new “DNA.” It starts with smaller cars, fueled by electricity and hydrogen (fuel cell technology). It also begins with an understanding that the cars used in many mundane urban operations today – for example getting to the market or pick up the kids at school – are over-engineered. They are far larger than is needed for most trips, their capacity for speed exceeds urban requirements and their range between refueling is also more than needed.

The authors would re-engineer urban vehicle to the needs of metropolitan dwellers, an “ultra-small vehicle” (USV). The designs proposed include far lighter cars that can be easily “folded” up to minimize parking space requirements. Cars would be connected to one another by wireless technology, all but eliminating the possibility of collisions. The cars would be small enough that they could be assigned special dedicated lanes on current freeways and streets. Travel would be less congested because the dedicated lanes would have a far higher vehicle capacity, while the interconnectedness would allow cars to safely operate closer to one another.

The combination of electricity, hydrogen, wireless technology and the USV would bring additional benefits. This would permit improved vehicle routing, as drivers would be advised take alternate less congested routes. This would also, in time, lead to self-drive cars, about which Randal O’Toole has recently written, made possible by the use of wireless technology and that dedicated lanes would make possible.

Empowering Transit Riders through Car Sharing

Car sharing is an important part of this future, for dwellers of dense urban cores, according to Reinventing the Automobile. The author’s note that car sharing can solve the “first mile-last mile” problem making it possible for transit users to speed up their trips by not having to walk long distances to and from transit stops. Indeed, car sharing programs are set to be adopted in urban cores with some of the world’s best transit systems, such as Paris, and London. Privately operated car sharing systems have been established in a number of US metropolitan areas, such as Atlanta, Denver and San Francisco.

Progress with Conventional Strategies

The longer term vision of the MIT Press authors may take a while to unfold, but we can already see potential for progress. Just this week, “super-car” developer Gordon Murray announced development of an urban car (the T25), smaller than the “Smart,” which would achieve nearly 60 miles per gallon, with plans for marketing within two years. Volkswagen has developed a “1-litre” car, which would achieve 235 miles per gallon on diesel fuel. All of this makes the 51 mile per gallon Toyota Prius seem gluttonous by comparison

These developments and the Reinventing the Automobile vision show that it is unnecessary to tell people in America (or Europe or the developiung world) that they must give up their automobiles. That is good news. The social engineering approaches requiring people to move from the suburbs to dense urban cores and travel by slower, less frequent transit are incapable of achieving serious environmental gains (see below) and can not seriously be considered progress or desirable by most people in advanced countries.

The Superiority of Technology

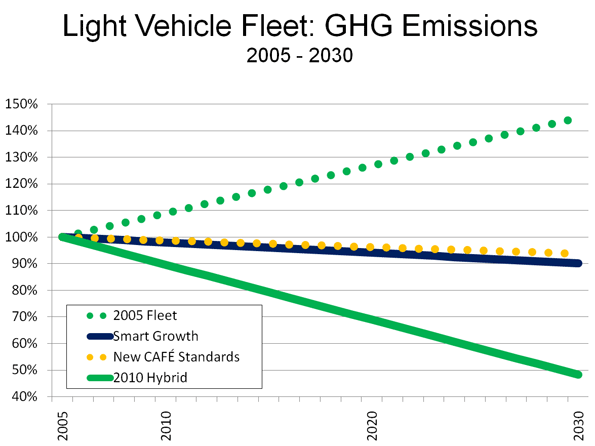

This is illustrated by recent developments in automobile technology and research (Figure).

- Before the adoption of the new 2020 and 2016 new car fuel economy standards, the US light vehicle fleet was on track to increase its greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions nearly 50% from 2005 to 2030 (the green dotted line in the figure).

- As a result of the new fuel economy standards, Department of Energy projections indicate that greenhouse gas emissions from light vehicles will be one-third less by 2030 compared to the 2005 fleet (the yellow dotted line), and this is at the standard projected driving increase rates that could well be high.

- The smart growth strategies of land rationing, densification and discouraging driving would produce, at best, a marginal reduction in GHG emissions, using the mid-point of the recent proponent research (Moving Cooler), indicated by the solid blue line. Actually, this overstates the impact of smart growth, since it discounts the substantial GHG emissions gains that result from higher fuel consumption in more congested traffic produced by densification.

- The potential for technological advance is illustrated by the green solid line, which estimates the GHG emissions from light vehicles in 2030 if the average fuel economy were equal to today’s best hybrid technology.

Overall auto-centered technology-based strategies – such as the improved fuel economy standards and the hybrid fuel economy – would each produce about 15 times as much benefit as the smart growth strategies proposed by such studies as Moving Cooler. This approach would not only be far more productive in terms of environmental improvement but would not require interfering with people’s lives in ways that would require longer trips times, less convenience, seriously retarded job access and, inevitably, fewer jobs and lower levels of economic growth.

Technology: The Only Way

It would be a mistake – and likely political folly – to force a re-engineering our way of life in order to enact strategies with dubious environmental benefits. In the final analysis, personal mobility must be retained and expanded, because there is no alternative that is acceptable to people, whatever system of government they happen to live under. Reinventing the Automobile paints the most optimistic picture to date and, if given due serious treatment, could prove a debate changer.

Photograph: Manila suburbs

Wendell Cox is a Visiting Professor, Conservatoire National des Arts et Metiers, Paris. He was born in Los Angeles and was appointed to three terms on the Los Angeles County Transportation Commission by Mayor Tom Bradley. He is the author of “War on the Dream: How Anti-Sprawl Policy Threatens the Quality of Life.”

“High Rise or House with Yard” stands alone in claiming that New York City is less costly than its suburbs. The most recent (and authoritative) ACCRA cost of living index for Brooklyn is a

“High Rise or House with Yard” stands alone in claiming that New York City is less costly than its suburbs. The most recent (and authoritative) ACCRA cost of living index for Brooklyn is a  Yet Houston scored better than any metropolitan area on the list except for much smaller Stockholm. As late as 1985, Houston

Yet Houston scored better than any metropolitan area on the list except for much smaller Stockholm. As late as 1985, Houston  Biased High Speed Rail Projections: Given the overwhelming history of upwardly biased ridership and revenue projections in major transport projects, it seems far more likely that reducing the margins of error would produce projections with much smaller ridership numbers and major financial losses. Major research by Oxford University professor Bent Flyvbjerg, Nils Bruzelius (a Swedish transport consultant) and Werner Rottenberg (University of Karlsruhe and former president of the World Conference on Transport Research) covering 80 years of infrastructure projects found routine over-estimation of ridership and revenue (

Biased High Speed Rail Projections: Given the overwhelming history of upwardly biased ridership and revenue projections in major transport projects, it seems far more likely that reducing the margins of error would produce projections with much smaller ridership numbers and major financial losses. Major research by Oxford University professor Bent Flyvbjerg, Nils Bruzelius (a Swedish transport consultant) and Werner Rottenberg (University of Karlsruhe and former president of the World Conference on Transport Research) covering 80 years of infrastructure projects found routine over-estimation of ridership and revenue ( Combined, the fastest growing suburbs and exurbs with more than 25,000 population grew more than 3.5 million, while the municipalities outside the major metropolitan areas grew 1.5 million, for a combined growth of more than 5.0 million. The smaller high growth municipalities (under 25,000), nearly 1,200 of them, both major metropolitan and outside, grew another 2.5 million.

Combined, the fastest growing suburbs and exurbs with more than 25,000 population grew more than 3.5 million, while the municipalities outside the major metropolitan areas grew 1.5 million, for a combined growth of more than 5.0 million. The smaller high growth municipalities (under 25,000), nearly 1,200 of them, both major metropolitan and outside, grew another 2.5 million. Now, a number of interior urban areas are now within a day’s truck drive of the East Coast ports and those that are not are within two days. According to

Now, a number of interior urban areas are now within a day’s truck drive of the East Coast ports and those that are not are within two days. According to