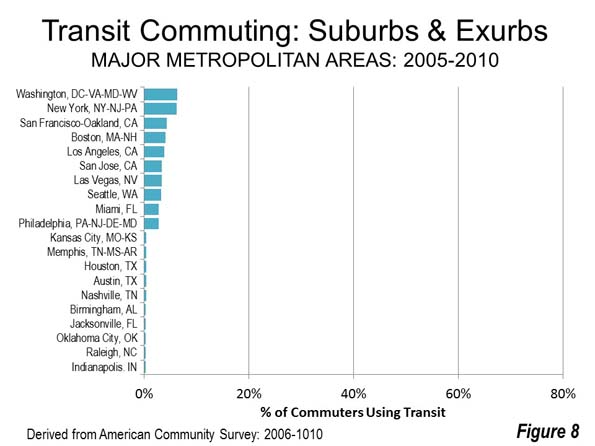

In its decades of unprecedented population growth, California was a land of superlatives. Regrettably, the superlatives have changed from mostly positive to largely negative. For example, the latest Census Bureau Supplemental Poverty Estimates, indicated that California continues to have the highest poverty rate of any state, after adjustment for housing costs (Figure 1). Not even Mississippi can compete with that, sitting 3.6 percentage points lower. California metropolitan areas undoubtedly resemble this shameful performance, though the Census Bureau does not provide data below the state level.

It should not be surprising that this backdrop is accompanied by some of the highest rates of housing overcrowding in the nation, according to the latest American Community Survey data (2015). Overcrowding is estimated by the number of people living in a dwelling unit per room. That raises the critical question of what is a room? The American Community Survey gives the following instruction on how to count rooms:

"When counting the number of rooms in a home for the American Community Survey (ACS), please count rooms separated by built-in archways or walls that extend out at least 6 inches and go from floor to ceiling. Include only whole rooms used for living purposes, such as living rooms, dining rooms, kitchens, bedrooms, finished recreation rooms, family rooms, enclosed porches suitable for year-round use, etc.

DO NOT count bathrooms, kitchenettes, strip or pullman kitchens, utility rooms, foyers, halls, open porches, balconies, unfinished attics, unfinished basements, or other unfinished space used for storage."

Overcrowding is generally defined as a household having more than one person (of any age) per room in a dwelling unit. Severe overcrowding is more than 1.5 persons per room. A household is the people living in a housing unit, whether a detached house, an apartment, a mobile home or other.

Degrees of Overcrowding

California generally leads in both overcrowding and severe overcrowding. The state’s share of overcrowded households in the nation is 27 percent, while the state has 30 percent of severely overcrowded households, almost 3 times its 11 percent share of households.

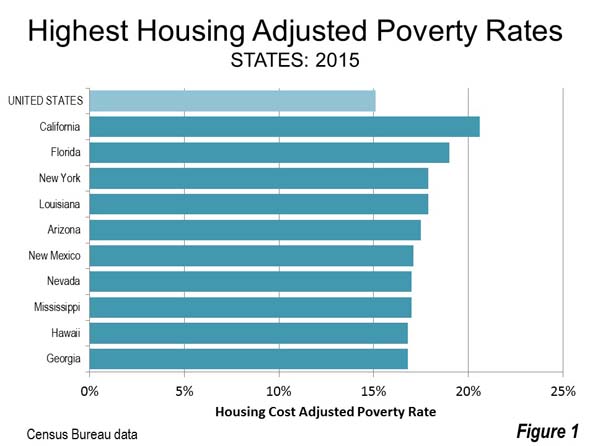

Only Hawaii has a higher severe overcrowding rate than California, at 3.8 percent of households California’s severe overcrowding rate is 2.9 percent. By contrast, average for the United States is a much lower 1.1 percent. Alaska has the third most severe overcrowding rate, at 2.3 percent, while New York has the fourth most severe overcrowding, at 2.1 percent. Arizona ranks fifth at 1.5 percent (Figure 2).

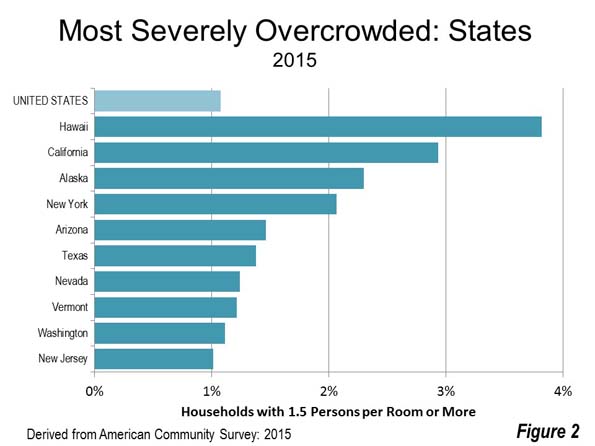

The situation is similar with respect to basic overcrowding, more than one person per room. Hawaii also leads in this category at 9.7 percent, followed by California at 8.4 percent. The national overcrowding rate is 3.4 percent. Again, Alaska ranks third at 6.1 percent, followed by New York and 5.4 percent and Texas at 4.9 percent (Figure 3).

Metropolitan Areas

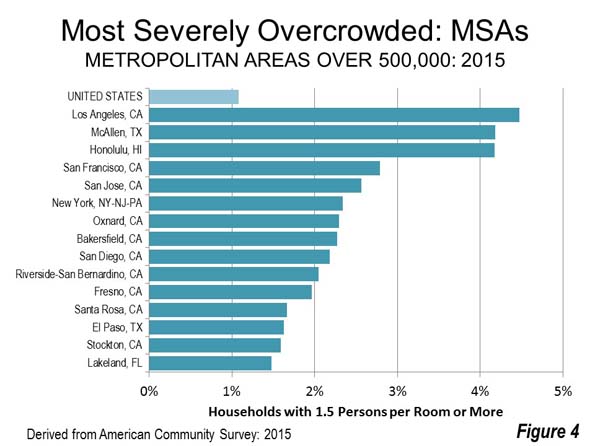

California metropolitan areas dominate in terms n both of the highest severe overcrowding rates and the highest overcrowding rates, to a far greater extent than one would expect from a highly developed, still affluent state.

California is home to 12 of the 106 metropolitan areas with more than 500,000 population (as of 2015). 10 of the 15 most severely overcrowded metropolitan areas are in California. My birthplace of Los Angeles has the worst rate in the United States, with 4.5 percent of its households in living in severely overcrowded conditions. This is more than four times the national rate of 1.1 percent. McAllen, Texas, in the Rio Grande Valley, is the second most severely overcrowded (4.2 percent), leading the third ranked Honolulu (4.2 percent) in the second digit.

Two of California’s and the nation’s most wealthy metropolitan areas are among the most severely overcrowded (more than 1.5 persons per room), both in the San Francisco Bay Area. These include San Francisco itself (#4) and San Jose (#5). New York is the sixth most severely overcrowded.

Other California metropolitan areas among the most severely overcrowded are Oxnard (#7), in the Los Angeles area, Bakersfield (#8) and Fresno (#11) in the San Joaquin Valley, San Diego (#9), Riverside San Bernardino (#10) in the Los Angeles area as well as Santa Rosa (#12) and Stockton (#14) in the San Francisco Bay Area (Figure 4).

Only two of California’s metropolitan areas with more than 500,000 residents do not rank in the most severely overcrowded metropolitan areas, Sacramento and Modesto.

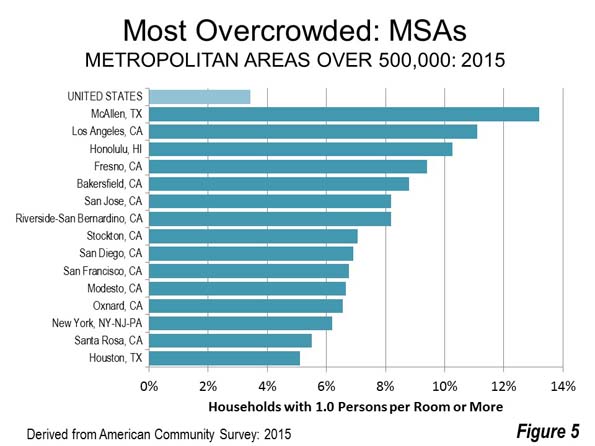

California’s dominance in basic overcrowding (over one person per room) is more complete, with 11 of its 12 largest metropolitan areas represented in the most overcrowded 15. Only Sacramento was exempted.

The same three metropolitan areas lead the pack, though in a somewhat different order. McAllen has an overcrowding rate of 13.2 percent, nearly 4 times the national rate of 3.4 percent. Los Angeles is the second most overcrowded, at 11.1 percent, while Honolulu repeats its third ranking at 10.3 percent.

The next at nine most overcrowded metropolitan areas are all in California, including Fresno (#4), Bakersfield (#5), San Jose (#6), Riverside-San Bernardino (#7), Stockton (#8), San Diego (#9),

San Francisco (#10), Modesto (#11), in the San Joaquin Valley and Oxnard (#12). Santa Rosa has the 14th largest overcrowding rate (Figure 5).

Contributing Factors

Two characteristics stand out with respect to the states and metropolitan areas most overcrowded, high international immigration rates and high housing costs. High housing costs were cited as a factor in California’s high overcrowding rates by the state Legislative Analyst. High housing costs are also a problem in Hawaii and New York, which are among the 10 most crowded states in both categories as are there largest metropolitan areas. In addition, states that are magnets for international immigration are also represented among the most overcrowded, such as California, New York, Arizona, New Mexico and Nevada.

Overcrowding has important social consequences, especially for children. For example, Claudia D. Solari at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill and Robert D. Mare of UCLA found in research focused on the city of Los Angeles that overcrowded housing significantly harms children, regardless of socioeconomic characteristics, negatively impacting school achievement, behavior and physical health. They conclude that these factors can persist throughout life, affecting their future socioeconomic status and adult well-being.”

California, with its progressive ideals, needs to match its performance with its rhetoric. The state’s working class is clearly being hemmed in, and face a future that is hardly that promised by its political class.

Wendell Cox is principal of Demographia, an international public policy and demographics firm. He is a Senior Fellow of the Center for Opportunity Urbanism (US), Senior Fellow for Housing Affordability and Municipal Policy for the Frontier Centre for Public Policy (Canada), and a member of the Board of Advisors of the Center for Demographics and Policy at Chapman University (California). He is co-author of the “Demographia International Housing Affordability Survey” and author of “Demographia World Urban Areas” and “War on the Dream: How Anti-Sprawl Policy Threatens the Quality of Life.” He was appointed to three terms on the Los Angeles County Transportation Commission, where he served with the leading city and county leadership as the only non-elected member. He served as a visiting professor at the Conservatoire National des Arts et Metiers, a national university in Paris.

Photo: Downtown Los Angeles toward the Hollywood Hills and the San Fernando Valley (by author)