For decades, those who know best have been chronicling the death of the suburbs. In every new announcement of demographic data, they find evidence that people are “moving back” to the core cities, even though they never moved away. The coverage of the latest Bureau of the Census city population estimates set a new standard. “Cities Grow at Suburb’s Expense During Recession” was the headline in The Wall Street Journal. The New York Daily News headlined “Census Shows Cities are Growing More Quickly than Suburbs.”

Robert E. Lang, co-director of Washington’s Metropolitan Institute at Virginia Tech noted that inner suburbs that have developed transit systems grew more last year and that others will begin to grow faster in the future. Lang specifically cites the Washington, DC suburbs of Alexandria and Arlington. William Frey of the Brookings Institution told Time magazine that the cities are “a lot better” able to withstand the “ups and downs” in the economy.

This is something for which no evidence was reported, but it was the “inside-the-beltway” (Washington) spin that Time and other media have been eager to adopt. Even the latest government numbers still showed the suburbs with a growth rate more than 20 percent above that of the core cities.

Premature Death Syndrome?

Despite the spin, an analysis of the 51 metropolitan areas with more than 1,000,000 population indicates that the nation’s suburbs are in no danger of being displaced as growth leaders by the central city. To start with, suburbs represent nearly 75 percent of the nation’s major metropolitan population. Further, the overwhelming evidence is that people continue to move out of the core cities in far larger numbers than they are moving in (net domestic migration).

In 2008, the core cities accounted for 23 percent of growth in the largest metropolitan areas. This is up from the decade annual average of 16 percent (Note 1). But this improvement is not the result of more people moving to the core cities but a huge decline in domestic migration, which has driven suburban growth for decades. Thus, the story in the latest census estimates is not that the cities are growing faster. It is rather that people are generally staying put amidst the steepest economic decline since the Great Depression. Stunted hopes, not a sudden enthusiasm for urban living, have driven the relative change.

| Table 1 |

| Metropolitan Area, Suburban and Core City Population: 2000-2008 |

| Metropolitan Areas Over 1,000,000 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

Metropolitan Area |

Suburbs |

Core City |

| Metropolitan Area |

2000 |

2008 |

Change |

2000 |

2008 |

Change |

2000 |

2008 |

Change |

Share of Growth |

| Atlanta |

4,282 |

5,376 |

1,094 |

3,861 |

4,838 |

977 |

421 |

538 |

117 |

11% |

| Austin |

1,266 |

1,653 |

387 |

602 |

895 |

293 |

664 |

758 |

94 |

24% |

| Baltimore |

2,557 |

2,667 |

110 |

1,909 |

2,030 |

122 |

649 |

637 |

(12) |

-11% |

| Birmingham |

1,053 |

1,118 |

64 |

811 |

889 |

77 |

242 |

229 |

(13) |

-21% |

| Boston |

4,402 |

4,523 |

121 |

3,813 |

3,914 |

101 |

589 |

609 |

20 |

16% |

| Buffalo |

1,169 |

1,124 |

(45) |

877 |

853 |

(24) |

292 |

271 |

(21) |

|

| Charlotte |

1,340 |

1,702 |

362 |

770 |

1,014 |

244 |

570 |

687 |

117 |

32% |

| Chicago |

9,118 |

9,570 |

452 |

6,222 |

6,717 |

494 |

2,896 |

2,853 |

(43) |

-9% |

| Cincinnati |

2,015 |

2,155 |

141 |

1,683 |

1,822 |

138 |

331 |

333 |

2 |

1% |

| Cleveland |

2,148 |

2,088 |

(60) |

1,671 |

1,655 |

(17) |

477 |

434 |

(43) |

|

| Columbus |

1,620 |

1,773 |

154 |

904 |

1,018 |

114 |

716 |

755 |

39 |

26% |

| Dallas-Fort Worth |

5,196 |

6,300 |

1,104 |

4,006 |

5,020 |

1,014 |

1,190 |

1,280 |

89 |

8% |

| Denver |

2,194 |

2,507 |

313 |

1,638 |

1,908 |

270 |

556 |

599 |

43 |

14% |

| Detroit |

4,458 |

4,425 |

(32) |

3,512 |

3,513 |

1 |

945 |

912 |

(33) |

|

| Hartford |

1,151 |

1,191 |

40 |

1,027 |

1,066 |

40 |

124 |

124 |

(0) |

0% |

| Houston |

4,740 |

5,728 |

989 |

2,761 |

3,486 |

725 |

1,978 |

2,242 |

264 |

27% |

| Indianapolis |

1,531 |

1,715 |

184 |

749 |

917 |

168 |

782 |

798 |

16 |

9% |

| Jacksonville |

1,126 |

1,313 |

187 |

390 |

505 |

116 |

737 |

808 |

71 |

38% |

| Kansas City |

1,843 |

2,002 |

159 |

1,442 |

1,563 |

122 |

401 |

439 |

38 |

24% |

| Las Vegas |

1,393 |

1,866 |

473 |

909 |

1,307 |

399 |

484 |

558 |

74 |

16% |

| Los Angeles |

12,401 |

12,873 |

472 |

8,697 |

9,039 |

342 |

3,704 |

3,834 |

130 |

28% |

| Louisville |

1,165 |

1,245 |

80 |

613 |

687 |

74 |

552 |

557 |

6 |

7% |

| Memphis |

1,208 |

1,224 |

16 |

518 |

554 |

36 |

690 |

670 |

(20) |

-130% |

| Miami |

5,027 |

5,415 |

388 |

4,663 |

5,002 |

338 |

363 |

413 |

50 |

13% |

| Milwaukee |

1,502 |

1,549 |

47 |

905 |

945 |

40 |

597 |

604 |

8 |

16% |

| Minneapolis-St. Paul |

2,982 |

3,230 |

248 |

2,599 |

2,847 |

248 |

383 |

383 |

0 |

0% |

| Nashville |

1,318 |

1,551 |

233 |

772 |

954 |

183 |

546 |

596 |

51 |

22% |

| New Orleans |

1,316 |

1,134 |

(182) |

832 |

822 |

(10) |

484 |

312 |

(172) |

|

| New York |

18,353 |

19,007 |

653 |

10,338 |

10,643 |

305 |

8,016 |

8,364 |

348 |

53% |

| Oklahoma City |

1,098 |

1,206 |

108 |

590 |

654 |

64 |

508 |

552 |

44 |

41% |

| Orlando |

1,657 |

2,055 |

398 |

1,464 |

1,824 |

360 |

193 |

231 |

37 |

9% |

| Philadelphia |

5,693 |

5,838 |

146 |

4,179 |

4,391 |

212 |

1,514 |

1,447 |

(66) |

-46% |

| Phoenix |

3,279 |

4,282 |

1,003 |

1,952 |

2,714 |

762 |

1,326 |

1,568 |

242 |

24% |

| Pittsburgh |

2,429 |

2,351 |

(78) |

2,095 |

2,041 |

(54) |

334 |

310 |

(24) |

|

| Portland |

1,936 |

2,207 |

271 |

1,406 |

1,650 |

244 |

530 |

558 |

28 |

10% |

| Providence |

1,587 |

1,597 |

10 |

1,413 |

1,425 |

12 |

174 |

172 |

(2) |

-23% |

| Raleigh |

804 |

1,089 |

284 |

514 |

696 |

182 |

290 |

393 |

102 |

36% |

| Richmond |

1,100 |

1,226 |

126 |

902 |

1,024 |

121 |

198 |

202 |

4 |

3% |

| Rochester |

1,042 |

1,034 |

(8) |

822 |

827 |

5 |

219 |

207 |

(13) |

|

| Riverside-San Bernardino |

3,278 |

4,116 |

838 |

3,020 |

3,821 |

800 |

258 |

295 |

38 |

4% |

| Sacramento |

1,809 |

2,110 |

301 |

1,399 |

1,646 |

247 |

409 |

464 |

55 |

18% |

| St. Louis |

2,724 |

2,841 |

116 |

2,378 |

2,486 |

109 |

347 |

354 |

7 |

6% |

| Salt Lake City |

973 |

1,116 |

143 |

791 |

934 |

143 |

182 |

182 |

(0) |

0% |

| San Antonio |

1,719 |

2,031 |

312 |

555 |

680 |

125 |

1,164 |

1,351 |

187 |

60% |

| San Diego |

2,825 |

3,001 |

176 |

1,597 |

1,722 |

124 |

1,228 |

1,279 |

51 |

29% |

| San Francisco |

4,137 |

4,275 |

137 |

3,360 |

3,466 |

106 |

778 |

809 |

31 |

23% |

| San Jose |

1,740 |

1,819 |

79 |

841 |

871 |

29 |

899 |

948 |

50 |

63% |

| Seattle |

3,052 |

3,345 |

292 |

2,489 |

2,746 |

258 |

564 |

599 |

35 |

12% |

| Tampa-St. Petersburg |

2,404 |

2,734 |

329 |

2,100 |

2,393 |

293 |

304 |

341 |

37 |

11% |

| Tucson |

849 |

1,012 |

163 |

359 |

470 |

111 |

489 |

542 |

52 |

32% |

| Virginia Beach |

1,580 |

1,658 |

78 |

1,346 |

1,424 |

78 |

234 |

234 |

(0) |

0% |

| Washington |

4,821 |

5,358 |

537 |

4,249 |

4,766 |

517 |

572 |

592 |

20 |

4% |

| Total |

152,409 |

166,323 |

13,914 |

109,318 |

121,097 |

11,778 |

43,090 |

45,226 |

2,136 |

15% |

| Population in 000s |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| City share column blank where both metropolitan area & city lost population |

|

|

|

|

|

| Metropolitan areas are named after their largest city or cities. The first city listed is the core city, except in Virginia Beach where the core city is Norfolk. |

| Italization indicates that core city was largely built out in 1960 and has annexed little or no territory. |

| Calculated from US Bureau of the Census data for county based metropolitan areas |

|

On close examination, the recent better relative performance of the cities stemmed from three factors, none of which involved people moving to them from the suburbs or anywhere else in the nation.

(1) Decline in Domestic Migration

Suburban growth has declined because the economic downturn has reduced the number of residents moving from one part of the country to another (domestic migrants). In 2008, net domestic migration fell to 30 percent below the decade average. The suburbs and exurbs were the largest gainers from domestic migration in past and have thus declined the most. This is not surprising, given the fact that a major part of subprime mortgage crisis that precipitated the Panic of 2008 (or the Great Recession) was the granting of mortgages to under-qualified households who stretched their financial resources to move to places where housing was the least expensive. Many of these households defaulted on their mortgages, were forced out of their houses and moved away.

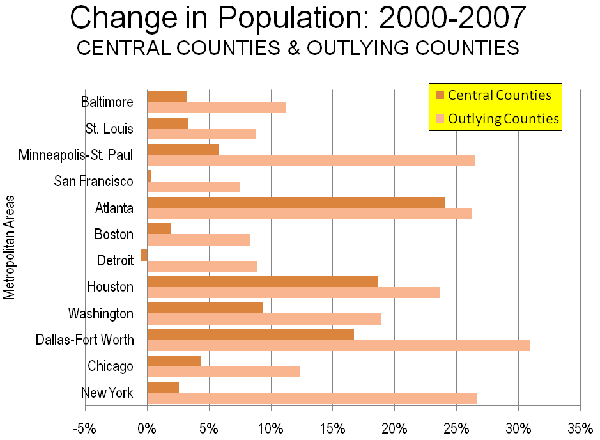

Nonetheless, as a new Bureau of the Census report indicated, in each of 12 large metropolitan areas analyzed the percentage growth in the exurbs was greater than in the core city. So even in the worst of times, the basic claim by the “inside-the-beltway” analysts and the media were totally off-base.

The slowdown in net domestic migration also has pushed up city population growth. Fewer people moved away from the core cities than in the past. This, however, is different from people moving into the cities from the suburbs.

It seems likely that stronger domestic migration gains will be restored to the suburbs when the economy improves. In the meantime, the growth rates of both the core cities and the suburbs have converged toward the natural rate of growth (births minus deaths).

(2) Net International Migration

County level data indicates that net international migration was only 9 percent below the decade average in 2008. The core cities have routinely attracted more international migrants than the suburbs. This, combined with a decline in domestic migration among metropolitan areas with more than 1,000,000 population helped to improve the growth rate of the core counties relative to the suburbs.

(3) Not Adding Up: City Estimates

Putting it frankly, the births minus deaths, plus domestic migration and international migration fall far short of the increases being reported in the core cities. This can be shown by examining the only core cities for which full “component of population change” data is available (natural increase, net domestic migration and net international migration). The Bureau of the Census does not release component data at any level of government below counties or their equivalents. In five cases, cities are fully consolidated with counties.

The consolidated city-counties are New York (an amalgamation of five counties, or boroughs), Philadelphia, San Francisco, Baltimore and Washington (DC). Some places referred to as consolidated city-county governments are not genuine amalgamations, because some separate cities remain, such as in Miami, Jacksonville, Louisville and Indianapolis. An examination of the components of population in the five genuinely consolidated city-county jurisdictions reveals huge unallocated discrepancies (the Bureau of the Census term is “residuals”).

Combining the births, deaths, net domestic migration and net international migration all of the five cities produces a population loss. The difference is the unallocated residual, which is huge in four of the five city-counties and a number of others and is small in most places that are not core cities.

This unexplained “residual” is largely the result of the Bureau of the Census population “challenge” program. Four of the five consolidated cities have mounted successful challenges to their estimates and have thus added significantly to their populations. In San Francisco and Washington, the challenges added more population than the 2000-2007 gain (2008 challenges are yet to be filed). In New York, the challenges amounted to 80 percent of the 2000-2007 growth (Table 2).

| Table 2 |

| Unallocated Residuals & Estimates Challenges : 2000-2007 |

| Fully Consolidated City-County Jurisdictions |

|

|

|

|

| |

Change in Population: 2000-2007 |

Unallocated Residual: 2000-2007 |

Successful Census Challenges: 2000-2007 |

|

|

|

|

| With Successful Challenges |

|

|

|

| Baltmore |

(8,400) |

34,700 |

56,400 |

| New York |

294,500 |

325,000 |

236,100 |

| San Francisco |

21,700 |

37,400 |

34,200 |

| Washington |

16,100 |

19,900 |

31,500 |

| Subtotal |

323,900 |

417,000 |

358,200 |

|

|

|

|

| No Successful Challenges |

|

|

|

| Philadelphia |

(65,200) |

(6,800) |

0 |

|

|

|

|

| Unallocated Residual: Population Change not accounted for in births, deaths, international migration or domestic migration |

| Calculated from US Bureau of the Census data. |

|

This is just the beginning of the story. More than one-half of the core city growth in the decade has been attributable to similar challenges. In contrast, only three percent of suburban population growth has been attributable to challenges. It does seem curious that the Bureau of the Census that has produced such erroneous estimates in places like New York (230,000), Atlanta’s Fulton County (110,000) and St. Louis (40,000), missed not a soul Los Angeles, Chicago, Cleveland, Phoenix and a host of other core cities and thousands of counties. The next census (2010) may be a good gauge of the challenge program’s accuracy, although it is not beyond imagining that anti-suburban elements may seek to politicize the results.

Inner Suburbs

Further, the theory of inner suburban growth is left wanting, even in the Washington area. Despite their transit improvements, between 2000 and 2008, Arlington and Alexandria lost 45,000 domestic migrants, both losing in every year except 2008 (in both cases, additions due to challenges were greater than the 2000-2007 population increase). Washington’s other inner suburbs, Fairfax County, Montgomery County and Prince Georges County are served by the same transit system (largely paid for by the taxpayers around the country), yet between them have lost another 240,000 domestic migrants between 2000 and 2008. On the other hand, the second ring suburbs have gained 112,000 migrants and the exurbs have gained 104,000 (See Figure). During the last year, the inner suburbs grew at approximately one-third the rate of the outer suburbs. And despite the subprime induced distress in the exurbs, the inner suburbs could achieve no better a rate. Analysts may trade anecdotes at coffee houses about people moving to the city or the inner suburbs from the exurbs or beyond. However, the Bureau of the Census data is clear. For every anecdote that that moves in, more than one moves out.

The Numbers Tell it All

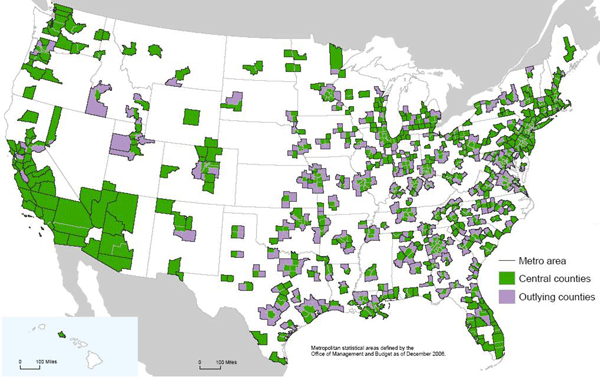

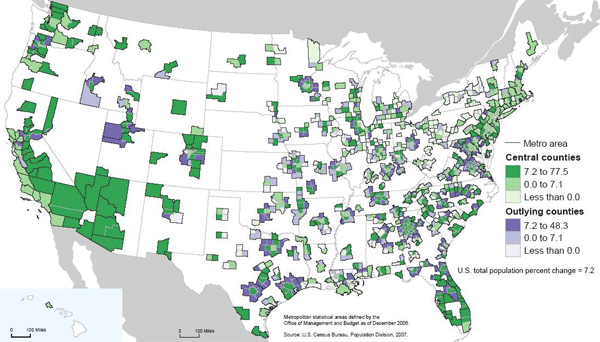

When the 2008 county and metropolitan area population estimates were published a few months ago, we showed that the central counties (Note 2) continue to lose residents at a rapid rate. Among the metropolitan areas with more than 1,000,000 population, central counties lost 4.6 million domestic migrants, while suburban counties gained 2.0 million domestic migrants between 2000 and 2008. Over the past year, the core counties lost a net 314,000 domestic migrants while the suburbs gained 197,000 (Table 3).

| Table 3 |

| Domestic Migration: Core and Suburban Counties: 2000-2008 |

| Metropolitan Areas over 1,000,000 Population |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

Latest Year: 2007-2008 |

Decade: 2000-2008 |

| Metropolitan Area |

Suburban |

Core |

Total |

Suburban |

Core |

Total |

| Atlanta |

32,925 |

10,126 |

43,051 |

395,836 |

(1,749) |

394,087 |

| Austin |

24,216 |

10,825 |

35,041 |

156,890 |

41,142 |

198,032 |

| Baltimore |

(6,000) |

(6,352) |

(12,352) |

32,952 |

(67,923) |

(34,971) |

| Birmingham |

5,658 |

(2,356) |

3,302 |

48,700 |

(25,755) |

22,945 |

| Boston |

(2,889) |

(5,372) |

(8,261) |

(154,086) |

(99,006) |

(253,092) |

| Buffalo |

(358) |

(4,127) |

(4,485) |

(5,933) |

(48,232) |

(54,165) |

| Charlotte |

21,327 |

13,060 |

34,387 |

125,223 |

93,513 |

218,736 |

| Chicago |

921 |

(43,031) |

(42,110) |

160,765 |

(667,507) |

(506,742) |

| Cincinnati |

3,803 |

(7,372) |

(3,569) |

65,905 |

(85,538) |

(19,633) |

| Cleveland |

861 |

(15,757) |

(14,896) |

14,726 |

(141,445) |

(126,719) |

| Columbus |

3,325 |

(826) |

2,499 |

64,211 |

(40,624) |

23,587 |

| Dallas-Fort Worth |

62,022 |

(18,847) |

43,175 |

514,011 |

(254,016) |

259,995 |

| Denver |

13,940 |

3,932 |

17,872 |

86,262 |

(50,881) |

35,381 |

| Detroit |

(17,020) |

(45,140) |

(62,160) |

(53,478) |

(273,695) |

(327,173) |

| Hartford |

379 |

(4,065) |

(3,686) |

10,789 |

(21,639) |

(10,850) |

| Houston |

38,559 |

(1,835) |

36,724 |

279,389 |

(89,222) |

190,167 |

| Indianapolis |

11,747 |

(5,040) |

6,707 |

113,378 |

(51,262) |

62,116 |

| Jacksonville |

8,723 |

(3,955) |

4,768 |

101,954 |

20,185 |

122,139 |

| Kansas City |

4,908 |

(3,495) |

1,413 |

57,007 |

(34,481) |

22,526 |

| Las Vegas (*) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Los Angeles |

(12,033) |

(103,004) |

(115,037) |

(232,281) |

(1,006,985) |

(1,239,266) |

| Louisville |

4,281 |

818 |

5,099 |

38,420 |

(9,798) |

28,622 |

| Memphis |

5,986 |

(10,533) |

(4,547) |

49,979 |

(52,412) |

(2,433) |

| Miami |

(18,598) |

(28,399) |

(46,997) |

31,551 |

(252,098) |

(220,547) |

| Milwaukee |

939 |

(7,382) |

(6,443) |

13,987 |

(86,392) |

(72,405) |

| Minneapolis-St. Paul |

1,179 |

(4,619) |

(3,440) |

61,162 |

(86,920) |

(25,758) |

| Nashville |

17,172 |

(547) |

16,625 |

128,921 |

(19,094) |

109,827 |

| New Orleans |

(2,520) |

22,856 |

20,336 |

(72,561) |

(233,021) |

(305,582) |

| New York |

(68,081) |

(76,018) |

(144,099) |

(672,435) |

(1,118,025) |

(1,790,460) |

| Oklahoma City |

5,707 |

(226) |

5,481 |

42,399 |

(10,302) |

32,097 |

| Orlando |

10,495 |

(7,342) |

3,153 |

174,428 |

55,611 |

230,039 |

| Philadelphia |

(9,639) |

(12,209) |

(21,848) |

36,553 |

(144,849) |

(108,296) |

| Phoenix |

22,614 |

28,463 |

51,077 |

117,550 |

411,697 |

529,247 |

| Pittsburgh |

1,169 |

(3,601) |

(2,432) |

5,221 |

(60,564) |

(55,343) |

| Portland |

10,641 |

7,355 |

17,996 |

106,163 |

(4,247) |

101,916 |

| Providence |

(3,983) |

(6,643) |

(10,626) |

(13,399) |

(34,136) |

(47,535) |

| Raleigh |

6,030 |

23,238 |

29,268 |

35,263 |

132,769 |

168,032 |

| Richmond |

5,625 |

937 |

6,562 |

76,608 |

(4,095) |

72,513 |

| Riverside-San Bernardino (*) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Rochester |

(425) |

(3,325) |

(3,750) |

(7,121) |

(36,181) |

(43,302) |

| Sacramento |

8,255 |

(3,731) |

4,524 |

97,304 |

34,798 |

132,102 |

| St. Louis |

561 |

(6,253) |

(5,692) |

17,988 |

(57,090) |

(39,102) |

| Salt Lake City |

1,407 |

(1,164) |

243 |

10,191 |

(41,646) |

(31,455) |

| San Antonio |

10,850 |

11,941 |

22,791 |

69,824 |

84,409 |

154,233 |

| San Diego (*) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| San Francisco |

4,092 |

1,414 |

5,506 |

(269,093) |

(80,543) |

(349,636) |

| San Jose |

(528) |

(2,097) |

(2,625) |

(6,119) |

(221,378) |

(227,497) |

| Seattle |

7,894 |

3,975 |

11,869 |

61,244 |

(38,132) |

23,112 |

| Tampa-St. Petersburg |

8,610 |

(2,100) |

6,510 |

169,346 |

91,106 |

260,452 |

| Tucson (*) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Virginia Beach |

(11,093) |

(4,430) |

(15,523) |

7,486 |

(15,941) |

(8,455) |

| Washington |

(16,637) |

(1,622) |

(18,259) |

(77,894) |

(43,457) |

(121,351) |

| Total |

197,017 |

(313,875) |

(116,858) |

2,015,186 |

(4,645,051) |

(2,629,865) |

| * Indicates no suburban county(ies) |

| Calculated from US Bureau of the Census data for county based metropolitan areas |

There is a simple test that the reporters and the analysts can apply. When the cores experience net domestic migration gains and the suburbs experience net domestic migration losses, only then can it be claimed that people are moving to the cores are gaining at the expense of the suburbs. The reality is that between 2000 and 2008, there was not a single instance out of the 51 metropolitan areas with more than 1,000,000 population where there was suburban net out-migration and core county net in-migration. There was one case in 2008, but it was an anomaly. The suburbs of New Orleans lost a modest number of domestic migrants, while the city gained strongly. This occurred because people moved back to the city in large numbers, after more than half left due to Hurricane Katrina.

Spin can change perceptions, but not reality. People are not moving from the suburbs to the core cities. The reverse continues to be true, even in the worst of times.

Note 1: Excludes New Orleans due to significant population variations from Hurricane Katrina.

Note 2: Counties are the smallest jurisdiction for which the Bureau of the Census publishes migration data.

Reference: Demographia 2000-2008 Metropolitan Area Population & Migration: http://www.demographia.com/db-metmic2004.pdf

Wendell Cox is a Visiting Professor, Conservatoire National des Arts et Metiers, Paris. He was born in Los Angeles and was appointed to three terms on the Los Angeles County Transportation Commission by Mayor Tom Bradley. He is the author of “War on the Dream: How Anti-Sprawl Policy Threatens the Quality of Life. ”

”