Much has been written about how suburbs have taken people away from the city and that now suburbanites need to return back to where they came. But in reality most suburbs of large cities have grown not from the migration of local city-dwellers but from migration from small towns and the countryside.

It is true that suburban areas have been growing strongly, while core cities have tended to grow much more slowly or even to decline. The predominance of suburban growth is not just an American phenomenon, but is fairly universal in the high income world).

This is true in both auto-oriented and transit oriented environments. Suburbs have accounted for more than 90 percent of growth in Japan’s metropolitan areas with more than 1,000,000 residents, both those with high transit market shares and those with high auto market shares, The same is true in Canada, Australia and New Zealand.

In Western Europe, where vaunted transit systems carry a far smaller share of travel than cars, all growth and then some has been in the suburbs, as overall core city populations have declined. Indeed, the same trend is well underway in middle and lower income world urban areas. In such places as Mexico City, Sao Paulo, Buenos Aires, Manila, Shanghai, Kolkata, and Jakarta, nearly all population growth has occurred in the suburbs, rather than the core cities.

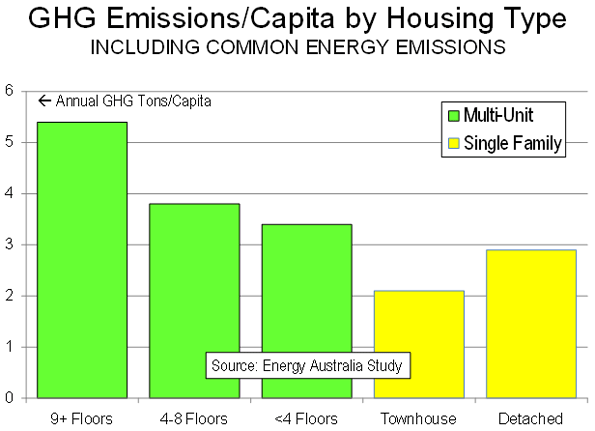

As the world faces a more expensive energy future and as efforts are intensified to reduce greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, it is sometimes suggested that people need to “move back” to the cities. This is a dubious and needless strategy, which reveals a fundamental misunderstanding of the dynamics of metropolitan growth.

Most suburban growth is not the result of declining core city populations, but is rather a consequence of people moving from rural areas and small towns to the major metropolitan areas. It is the appeal of large metropolitan places that drives suburban growth.

Larger metropolitan areas have more lucrative employment opportunities and generally have higher incomes than smaller metropolitan areas. This is particularly the case in developing countries. As a result, the big urban areas attract people seeking to escape what are often the stagnant or even declining economies in smaller areas.

There are, of course, significant individual exceptions. Virtually all of the first world core cities that have achieved a population of more than 400,000 – if they have not expanded their boundaries and did not have substantial empty land for development – experienced losses to 2000. Yet even in most of these cases, the majority of suburban growth was from outside the metropolitan areas, rather than from the core cities. For example:

- St. Louis is a champion among the ranks of population losers, having lost the greatest percentage of its population of any large municipality in the world, (dropping from nearly 860,000 in 1950 to 350,000 in 2000). Indeed, it may be fair to say that St. Louis has lost more of its population than any city since the Romans sacked Carthage. Yet, even in St. Louis, 60 percent of suburban growth was from outside the metropolitan area, rather than from the city.

- Few core cities have lost the nearly 1,000,000 residents that have fled Detroit since 1950. Yet, even in Detroit, 65 percent of suburban growth was from outside the metropolitan area, rather than from the city.

- The city of Chicago lost 725,000 residents between 1950 and 2000, yet 82 percent of the suburban growth was from outside the metropolitan area.

The city of Philadelphia lost 550,000 residents between 1950 and 2000, yet 76 percent of the suburban growth was from outside the metropolitan area (See lead picture of Philadelpia downtown).

The city of Philadelphia lost 550,000 residents between 1950 and 2000, yet 76 percent of the suburban growth was from outside the metropolitan area (See lead picture of Philadelpia downtown).- The central city of Paris lost approximately one-quarter of its population from 1965 to 2000 (675,000), while the suburbs gained nearly 3,850,000 residents. More than 80 percent of suburban Paris growth came from outside the region.

The central city of Lisbon experienced a 30 percent population decline from 1965 to 2000. Yet suburban Lisbon’s growth was 80 percent from outside.

The central city of Lisbon experienced a 30 percent population decline from 1965 to 2000. Yet suburban Lisbon’s growth was 80 percent from outside.

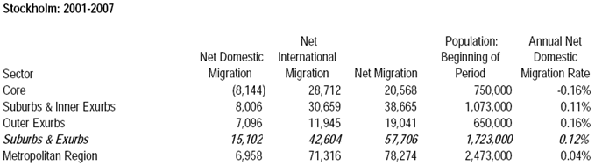

- Stockholm was another losing core city, yet more than 90 percent of the suburban growth came from smaller towns and cities.

- Despite Zurich’s nearly one-quarter population loss 83 percent of the suburban gains derived from outside the region.

The core city of Tokyo (which really doesn’t exist except as 23 separate subdivisions or kus of a city abolished during World War II) lost more than 700,000 residents from 1965 to 2000. Tokyo’s suburbs, however, attracted more than 90 percent of their growth from region.

The core city of Tokyo (which really doesn’t exist except as 23 separate subdivisions or kus of a city abolished during World War II) lost more than 700,000 residents from 1965 to 2000. Tokyo’s suburbs, however, attracted more than 90 percent of their growth from region.

In some metropolitan areas, smaller towns and rural areas contributed less to suburban growth. In Amsterdam, 50 percent of the suburban growth was from outside the metropolitan area. In Copenhagen, the number was 40 percent of the suburban growth while in Birmingham (UK) only 30 percent of the suburban gain was from outside.

In a few cases, both the core city losses were greater than the suburban gains, such as in Pittsburgh, Liverpool and Manchester. In these cases, it is fair to attribute all of the suburban gains to core city losses.

Unlike the cases above, however, most core cities gained population. This includes all in Canada, Australia and New Zealand and many in the United States. As a result, none of the suburban growth in the corresponding metropolitan areas can be attributed to an exodus from the city, because there, on balance, was no exodus.

Suburbanization is often characterized as reducing densities, but in fact it has done just the opposite. Most suburbanites come from smaller places; they may prefer suburbs because they are less dense, safer, or simply more manageable than the core cities. But they are also, almost invariably, more dense than where they lived before. Suburbanization is thus a densifying dynamic, albeit one that is less dramatic than preferred by many planners and architects.

In this sense, suburbs have to be seen not as the enemies of the city, as just a modern expression of urbanization. They are neither the enemies of the city, nor are their residents likely to move “back” there. You cannot move back to someplace you did not come from.

Wendell Cox is a Visiting Professor, Conservatoire National des Arts et Metiers, Paris. He was born in Los Angeles and was appointed to three terms on the Los Angeles County Transportation Commission by Mayor Tom Bradley. He is the author of “War on the Dream: How Anti-Sprawl Policy Threatens the Quality of Life.”

Forcing Density: Urban consolidation is destroying not only housing affordability, but also the character of Sydney itself. Sydney is an urban area of low density suburbs. It is also an urban area of high rise living. These two housing forms have combined with one of the world’s most attractive geographical settings to create an attractive and livable urban area.

Forcing Density: Urban consolidation is destroying not only housing affordability, but also the character of Sydney itself. Sydney is an urban area of low density suburbs. It is also an urban area of high rise living. These two housing forms have combined with one of the world’s most attractive geographical settings to create an attractive and livable urban area.