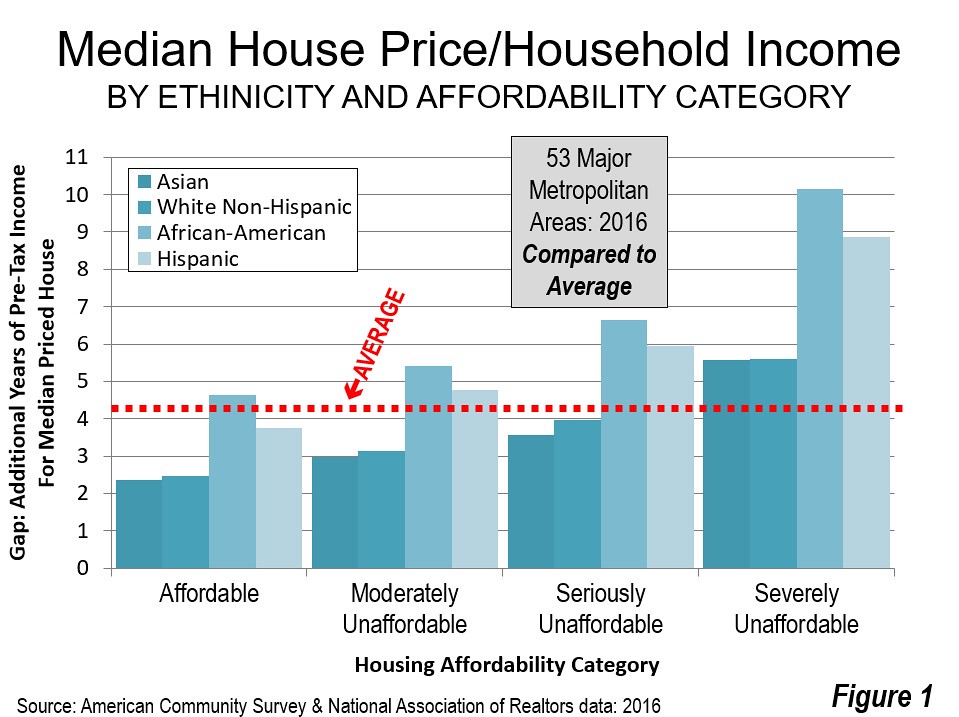

America’s most highly regulated housing markets are also reliably the most progressive in their political attitudes. Yet in terms of gaining an opportunity to own a house, the price impacts of the tough regulation mean profound inequality for the most disadvantaged large ethnicities, African-Americans and Hispanics.

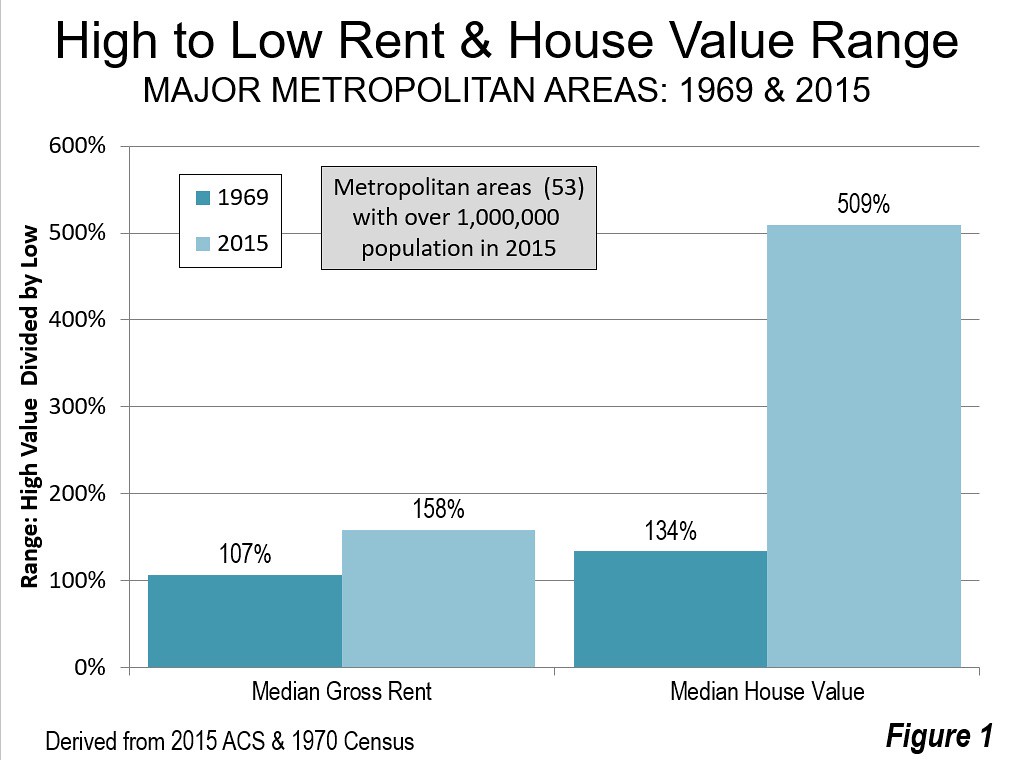

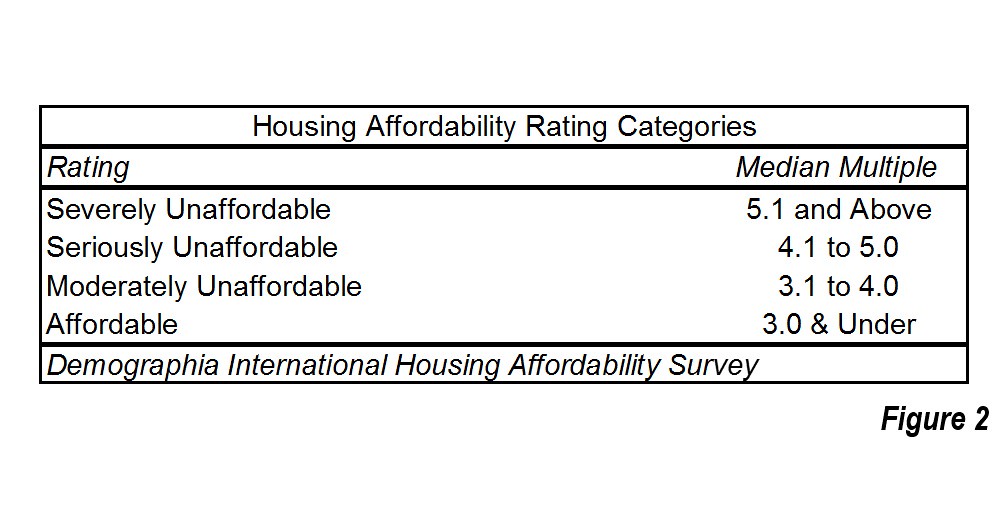

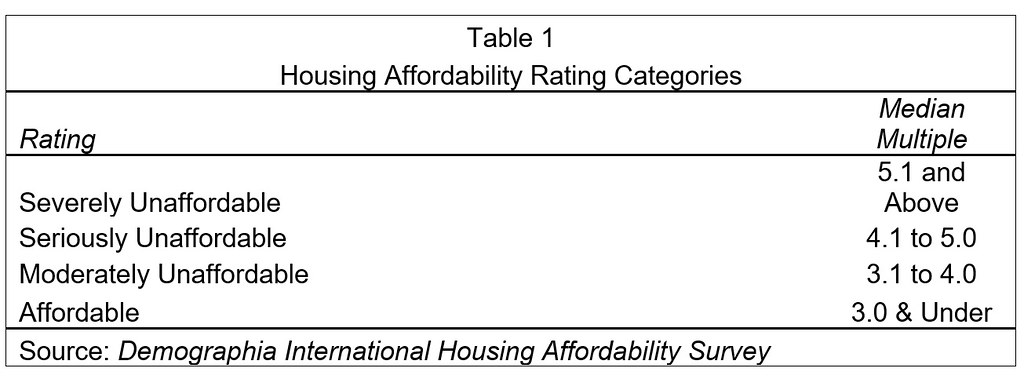

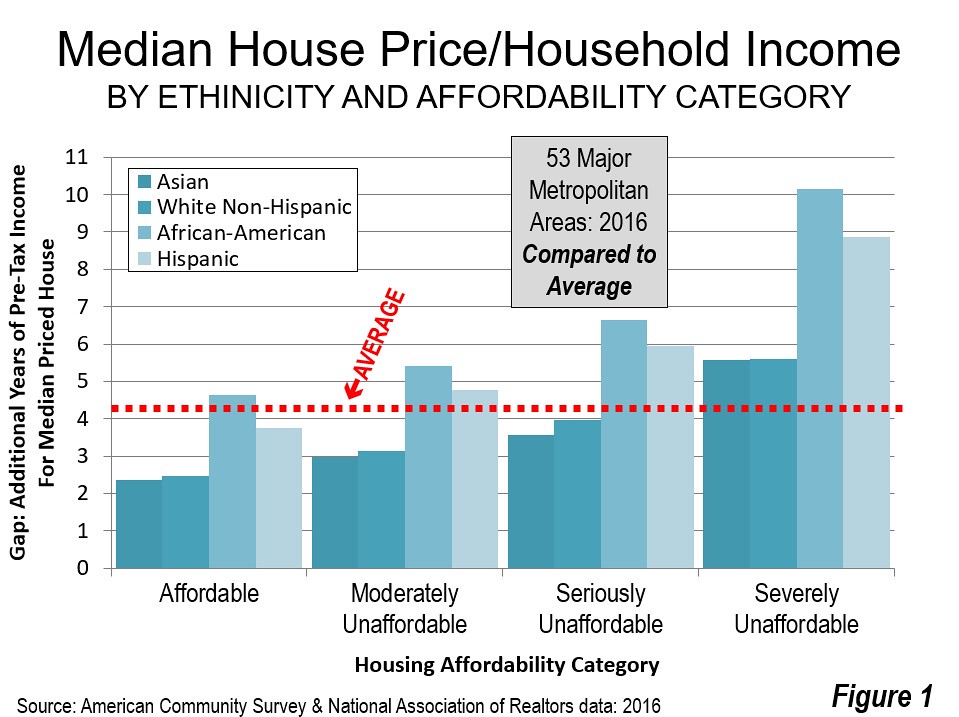

Based on the housing affordability categories used in the Demographia International Housing Affordability Survey for 2016 (Table 1), housing inequality by ethnicity is the worst among the metropolitan areas rated “severely unaffordable.” In these 11 major metropolitan area markets, the most highly regulated, median multiples (median house price divided by median household income) exceed 5.0. For African-Americans, the median priced house is 10.2 times median incomes. This is 3.7 more years of additional income than the overall average in these severely unaffordable markets, where median house prices are 6.5 times median household incomes. It is only marginally better for Hispanics, with the median price house at 8.9 times median household incomes, 2.4 years more than the average in these markets (Figure 1).

The comparisons with the 13 affordable markets (median multiples of 3.0 and less) is even more stark. For African-American households things are much better than in the more progressive and most expensive metropolitan areas. The median house prices is equal to 4.6 years of median income, 5.5 years less than in the severely affordable markets. Moreover, for African-Americans, housing affordability is only marginally worse than the national average in the affordable market.

Things are even better for Hispanics, who would find the median house price 3.8 times median incomes, 5.1 years less than in the severely affordable markets. This is better than the national average housing affordability.

Among the four markets rated “seriously unaffordable,” (median multiple from 4.1 to 5.0) the inequality is slightly less, with African-Americans finding median house prices equal to 2.2 years of additional income compared to average. The disadvantage for Hispanics is 1.5 years.

In contrast, inequality is significantly reduced in the less costly “moderately unaffordable” markets (median multiple of 3.1 to 4.0) and the “affordable” markets (median multiple of 3.0 and less).

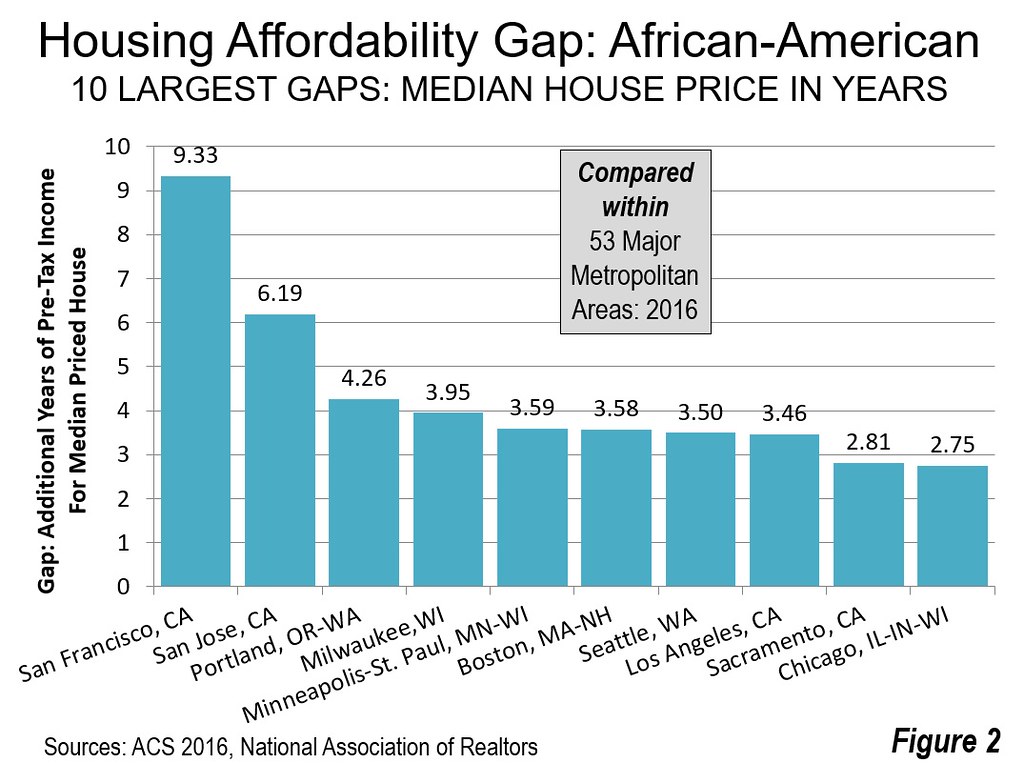

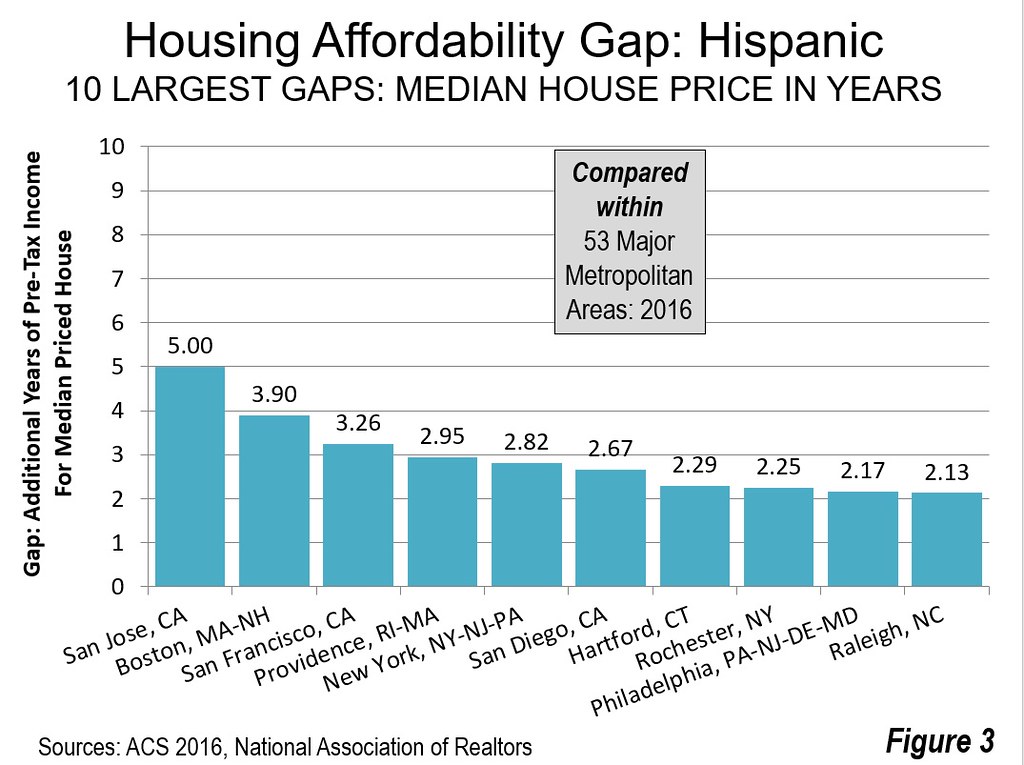

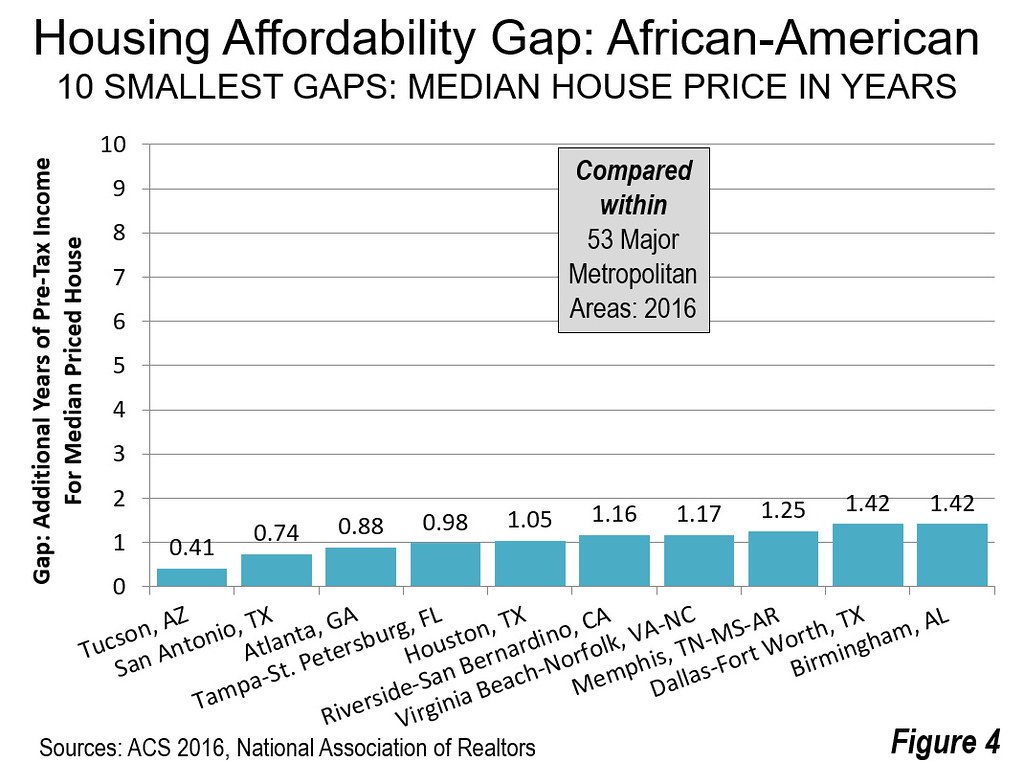

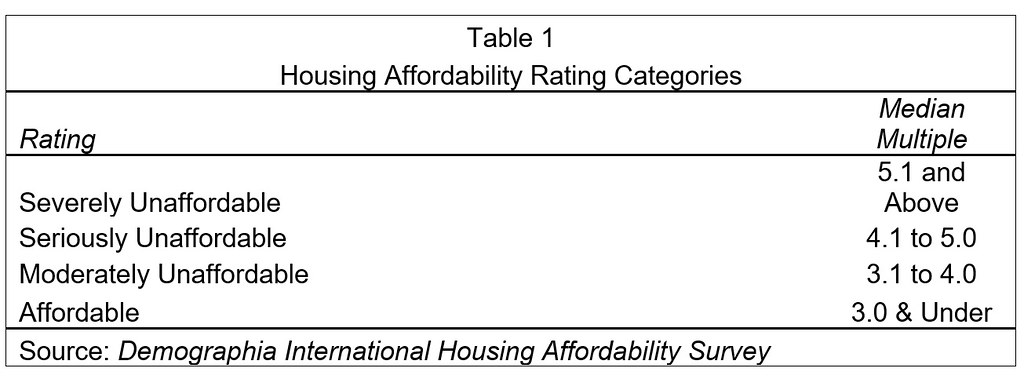

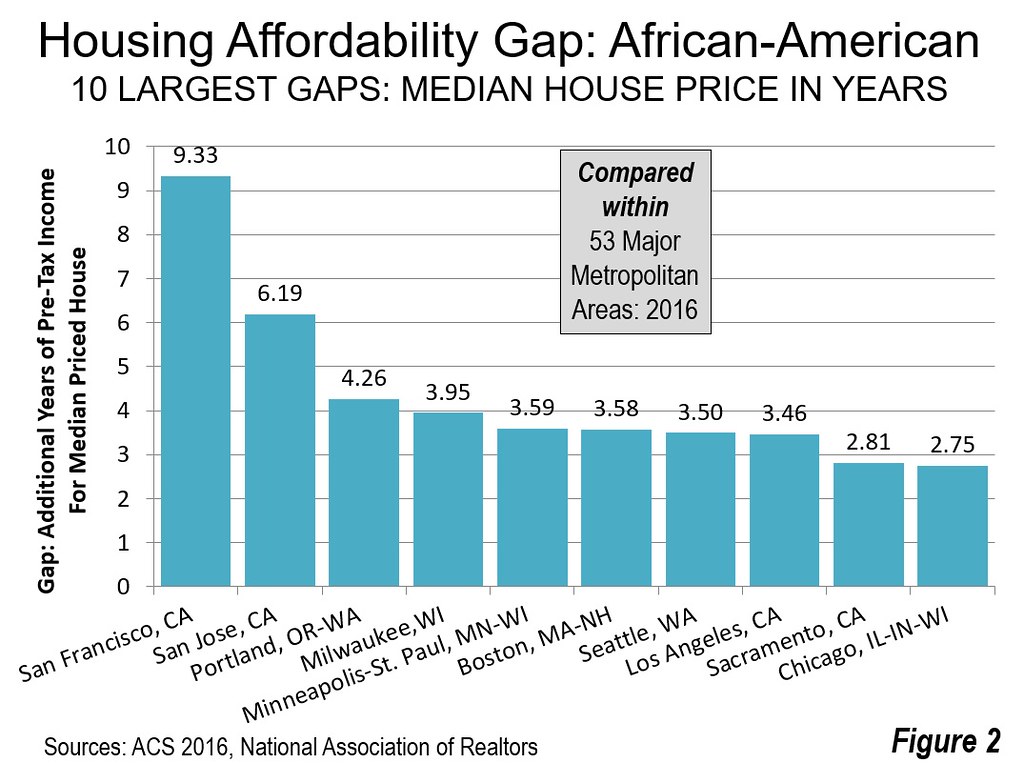

The discussion below describes the 10 largest and smallest housing affordability gaps for African-American and Hispanic households relative to the average household, within the particular metropolitan markets. The gaps within ethnicities compared to the affordable markets would be even more. The four charts all have the same scale (a top housing affordability gap of 10 years) for easy comparison.

able 2 illustrates housing affordability gaps by major metropolitan areas. There are also housing affordability ranking gap tables by African-American households (Table 3) and Hispanic households (Table 4).

Largest Housing Affordability Gaps: African American

African-Americans have the largest housing affordability inequality gap. And these gaps are most evident in some of the nation’s most progressive cities. The largest gap is in San Francisco, where the median income African-American household faces median house prices that are 9.3 years of income more than the average. In nearby San Jose ranks the second worst, where the gap is 6.2 years. Overall, the San Francisco Bay Area suffers by far the area of least housing affordability for African-Americans compared to the average household.

Portland, long the darling of the international urban planning community, ranks third worst, where the median income African-American household to purchase the median priced house. Milwaukee and Minneapolis – St. Paul ranked fourth and fifth worst followed by Boston, Seattle, Los Angeles, Sacramento and Chicago (Figure 2).

Largest Housing Affordability Gaps: Hispanics

Two of the three worst positions are occupied by the two metropolitan areas in the San Francisco Bay Area. The worst housing affordability gap for Hispanics is in San Jose, a more than one-quarter Hispanic metropolitan area where the median income Hispanic household would require 5.0 years of additional income to pay for the median priced house compared to the average. Boston ranks second worst at 3.9. San Francisco third worst at 3.3 years. Providence and New York rank fourth and fifth worst. The second five worst housing inequality for Hispanics is in San Diego, Hartford, Rochester, Philadelphia and Raleigh (Figure 3).

The San Francisco Bay Area: “Inequality City”

Perhaps no part of the country is more renowned for its progressive politics and politicians than the San Francisco Bay Area. Yet, in housing equality, the Bay Area is anything but progressive. If the African-American and Hispanic housing inequality measures are averaged, disadvantaged minorities face house prices that average approximately 6.25 years more years of median income in San Francisco and 5.60 more years of median income in San Jose.

Moreover, no one should imagine that recent state law authorizing a $4 billion “affordable housing” bond election will have any significant impact. According to the Sacramento Bee, voter approval would lead to 70,000 new housing units annually, when the need for low and very low income households is 1.5 million. The bond issue would do virtually nothing for the many middle-income households who are struggling to pay the insanely high housing costs California’s regulatory nightmare has developed.

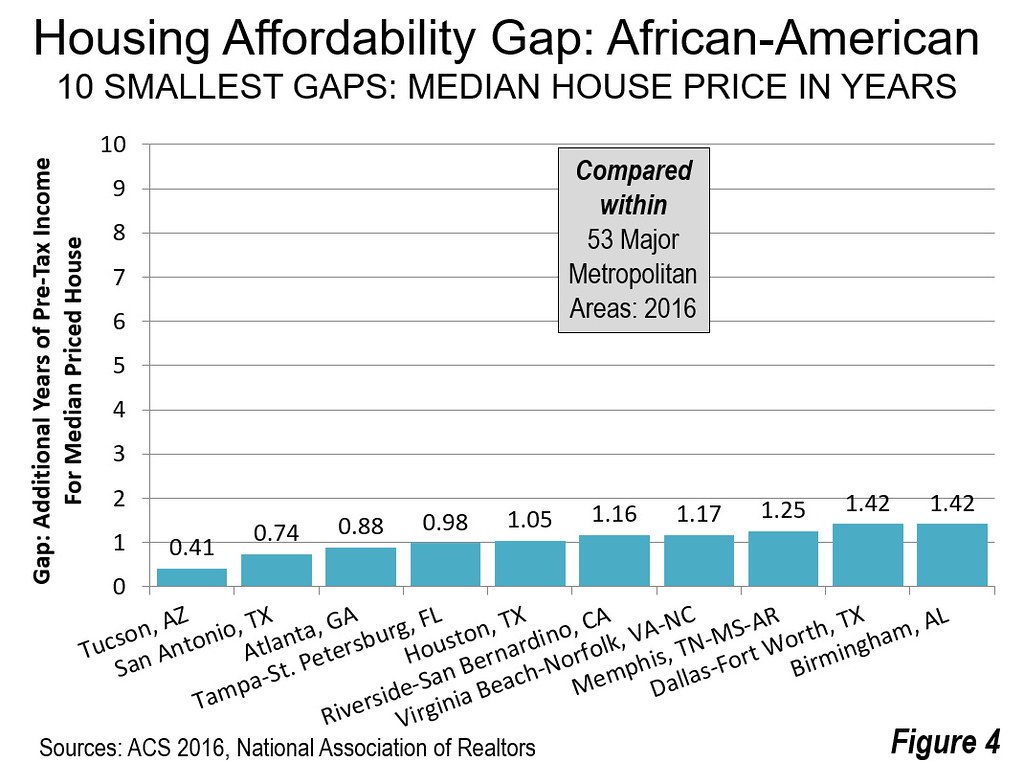

Smallest Housing Affordability Gaps: African-American

Tucson has the smallest housing affordability gap for African-Americans. In Tucson, the median income African-American household would pay approximately 0.4 years (four months) more in income for the median priced house than the average household. In San Antonio, Atlanta and Tampa – St. Petersburg, the housing affordability gaps are under 1.0. Houston, Riverside – San Bernardino, Virginia Beach – Norfolk, Memphis, Dallas – Fort Worth and Birmingham round out the second five. It may be surprising that eight of the metropolitan areas with the smallest housing affordability gaps for African-Americans are in the South and perhaps most surprisingly of all that one of the best, at number 10, is Birmingham. (Figure 4).

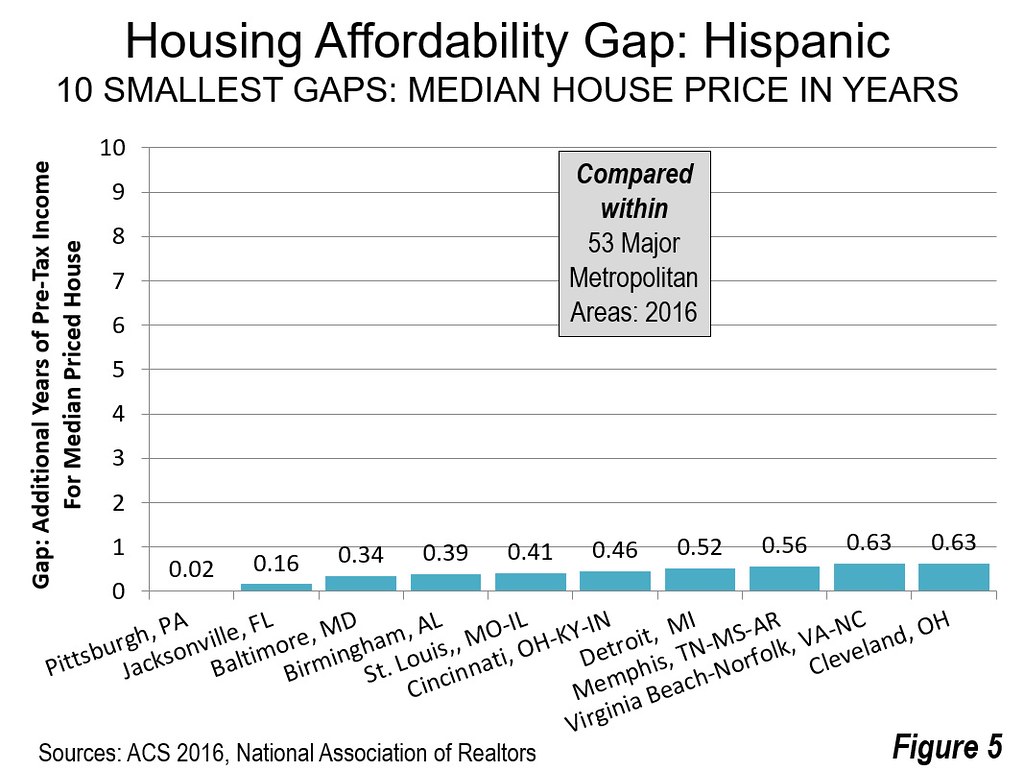

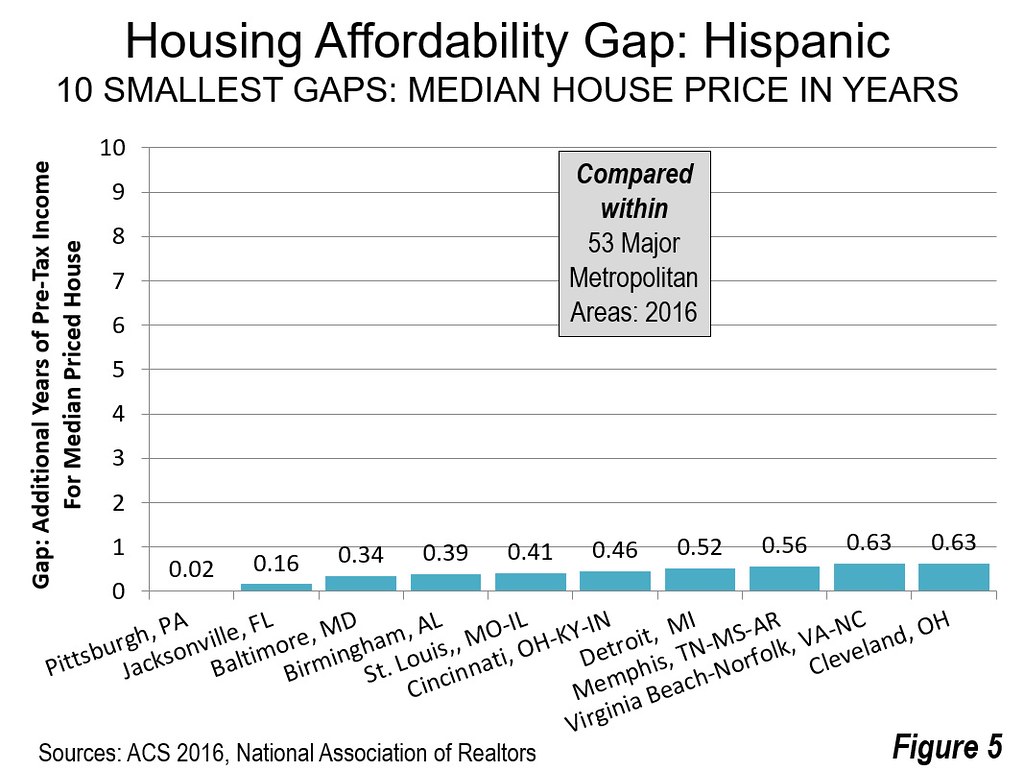

Smallest Housing Affordability Gaps: Hispanic

Among Hispanic households, the smallest housing affordability gap is in Pittsburgh, where the median priced house would require less than 10 days more in median income for a Hispanic household compared the overall average. In Jacksonville the housing affordability gap for Hispanics would be less than two months. In Baltimore, Birmingham, St. Louis and Cincinnati, the median house price is the equivalent of less than six months of median income for an Hispanic household. Detroit, Memphis, Virginia Beach – Norfolk and Cleveland round out the ten smallest housing affordability gaps for Hispanics (Figure 5).

Housing Affordability is the Best for Asians

Recent American Community Survey data indicated that Asians have median household incomes a quarter above those of White Non-– Hispanics. This advantage is also illustrated in the housing affordability data. Asians have better housing affordability than White Non-– Hispanics in 37 of the 53 major metropolitan areas (over 1 million population).

The Importance of Housing Opportunity

Housing opportunity is important. African-Americans and Hispanics already face challenges given their generally lower incomes. However, by no serious political philosophy, progressive or otherwise, should any ethnicity find themselves even further disadvantaged by political barriers, such as have been created by over-zealous land and housing regulators.

Wendell Cox is principal of Demographia, an international public policy and demographics firm. He is a Senior Fellow of the Center for Opportunity Urbanism (US), Senior Fellow for Housing Affordability and Municipal Policy for the Frontier Centre for Public Policy (Canada), and a member of the Board of Advisors of the Center for Demographics and Policy at Chapman University (California). He is co-author of the “Demographia International Housing Affordability Survey” and author of “Demographia World Urban Areas” and “War on the Dream: How Anti-Sprawl Policy Threatens the Quality of Life.” He was appointed to three terms on the Los Angeles County Transportation Commission, where he served with the leading city and county leadership as the only non-elected member. He served as a visiting professor at the Conservatoire National des Arts et Metiers, a national university in Paris.

| Table 2 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Housing Affordability Gap by Ethnicity: 2016 |

| 53 Major Metropolitan Areas (Over 1,000,000 Population) |

| Median Multiple (Median house price divided by median household income) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| MSA |

Median Multiple: All Households |

Median Multiple: African-American |

African American Housing Affordability Gap in Years |

Ranked Most to Least Equal: African-American |

Median Multiple:

Hispanic |

Hispanic Housing Affordability Gap in Years |

Ranked Most to Least Equal: Hispanic |

Exhibit: Median Multiple: Asian |

Exhibit: Median Multiple: White Non-Hispanic |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Atlanta, GA |

2.95 |

3.83 |

0.88 |

3 |

3.65 |

0.70 |

13 |

2.30 |

2.45 |

| Austin, TX |

4.00 |

5.69 |

1.69 |

19 |

5.04 |

1.04 |

24 |

3.23 |

3.52 |

| Baltimore, MD |

3.29 |

4.75 |

1.46 |

12 |

3.64 |

0.34 |

3 |

2.60 |

2.83 |

| Birmingham, AL |

3.57 |

4.99 |

1.42 |

10 |

3.96 |

0.39 |

4 |

2.95 |

3.02 |

| Boston, MA-NH |

5.11 |

8.69 |

3.58 |

47 |

9.02 |

3.90 |

52 |

4.67 |

4.62 |

| Buffalo, NY |

2.48 |

4.79 |

2.32 |

38 |

4.58 |

2.10 |

43 |

2.90 |

2.20 |

| Charlotte, NC-SC |

3.47 |

4.95 |

1.47 |

13 |

4.77 |

1.30 |

32 |

2.31 |

3.08 |

| Chicago, IL-IN-WI |

3.56 |

6.30 |

2.75 |

43 |

4.45 |

0.90 |

20 |

2.69 |

2.94 |

| Cincinnati, OH-KY-IN |

2.53 |

4.70 |

2.17 |

35 |

2.99 |

0.46 |

6 |

1.75 |

2.33 |

| Cleveland, OH |

2.54 |

4.50 |

1.96 |

27 |

3.17 |

0.63 |

10 |

1.49 |

2.16 |

| Columbus, OH |

2.91 |

4.78 |

1.87 |

24 |

4.10 |

1.19 |

30 |

2.50 |

2.68 |

| Dallas-Fort Worth, TX |

3.56 |

4.98 |

1.42 |

9 |

4.70 |

1.14 |

26 |

2.55 |

2.87 |

| Denver, CO |

5.34 |

7.64 |

2.29 |

37 |

7.40 |

2.05 |

42 |

5.33 |

4.76 |

| Detroit, MI |

4.01 |

6.71 |

2.70 |

41 |

4.53 |

0.52 |

7 |

2.56 |

3.48 |

| Grand Rapids, MI |

2.68 |

4.66 |

1.98 |

28 |

3.85 |

1.16 |

28 |

2.95 |

2.53 |

| Hartford, CT |

3.18 |

4.88 |

1.70 |

20 |

5.48 |

2.29 |

47 |

2.78 |

2.82 |

| Houston, TX |

3.52 |

4.57 |

1.05 |

5 |

4.68 |

1.15 |

27 |

2.54 |

2.65 |

| Indianapolis. IN |

2.82 |

4.89 |

2.07 |

31 |

4.45 |

1.63 |

38 |

2.48 |

2.50 |

| Jacksonville, FL |

3.71 |

5.15 |

1.43 |

11 |

3.88 |

0.16 |

2 |

3.32 |

3.38 |

| Kansas City, MO-KS |

2.95 |

4.96 |

2.00 |

30 |

3.97 |

1.02 |

23 |

2.64 |

2.68 |

| Las Vegas, NV |

4.37 |

6.36 |

1.98 |

29 |

5.19 |

0.82 |

16 |

3.63 |

3.85 |

| Los Angeles, CA |

7.69 |

11.15 |

3.46 |

45 |

9.74 |

2.05 |

41 |

6.68 |

6.03 |

| Louisville, KY-IN |

2.99 |

4.90 |

1.91 |

25 |

3.92 |

0.93 |

21 |

2.48 |

2.71 |

| Memphis, TN-MS-AR |

3.12 |

4.37 |

1.25 |

8 |

3.68 |

0.56 |

8 |

2.13 |

2.29 |

| Miami, FL |

5.94 |

7.58 |

1.64 |

17 |

6.64 |

0.70 |

12 |

4.39 |

4.68 |

| Milwaukee,WI |

3.93 |

7.88 |

3.95 |

49 |

5.79 |

1.86 |

40 |

2.78 |

3.33 |

| Minneapolis-St. Paul, MN-WI |

3.24 |

6.83 |

3.59 |

48 |

4.64 |

1.40 |

34 |

3.25 |

3.01 |

| Nashville, TN |

3.74 |

5.43 |

1.69 |

18 |

5.04 |

1.30 |

33 |

3.12 |

3.43 |

| New Orleans. LA |

3.85 |

6.42 |

2.57 |

40 |

5.02 |

1.17 |

29 |

4.01 |

2.93 |

| New York, NY-NJ-PA |

5.40 |

7.85 |

2.45 |

39 |

8.22 |

2.82 |

49 |

4.68 |

4.25 |

| Oklahoma City, OK |

2.74 |

4.81 |

2.07 |

32 |

3.62 |

0.88 |

19 |

2.52 |

2.45 |

| Orlando, FL |

4.28 |

6.00 |

1.72 |

22 |

5.21 |

0.94 |

22 |

2.93 |

3.60 |

| Philadelphia, PA-NJ-DE-MD |

3.42 |

5.69 |

2.28 |

36 |

5.59 |

2.17 |

45 |

3.02 |

2.82 |

| Phoenix, AZ |

4.01 |

5.54 |

1.53 |

14 |

5.07 |

1.06 |

25 |

3.17 |

3.62 |

| Pittsburgh, PA |

2.68 |

4.61 |

1.93 |

26 |

2.70 |

0.02 |

1 |

1.97 |

2.54 |

| Portland, OR-WA |

5.11 |

9.38 |

4.26 |

50 |

6.69 |

1.57 |

37 |

4.44 |

4.89 |

| Providence, RI-MA |

4.26 |

6.38 |

2.12 |

34 |

7.21 |

2.95 |

50 |

3.09 |

3.95 |

| Raleigh, NC |

3.46 |

5.01 |

1.56 |

15 |

5.59 |

2.13 |

44 |

2.47 |

3.12 |

| Richmond, VA |

3.74 |

5.44 |

1.70 |

21 |

4.61 |

0.87 |

18 |

2.75 |

3.14 |

| Riverside-San Bernardino, CA |

5.38 |

6.55 |

1.16 |

6 |

6.04 |

0.66 |

11 |

4.04 |

4.85 |

| Rochester, NY |

2.42 |

4.52 |

2.10 |

33 |

4.67 |

2.25 |

46 |

2.26 |

2.21 |

| Sacramento, CA |

5.00 |

7.81 |

2.81 |

44 |

6.21 |

1.21 |

31 |

4.63 |

4.46 |

| St. Louis,, MO-IL |

2.74 |

4.46 |

1.72 |

23 |

3.15 |

0.41 |

5 |

2.41 |

2.45 |

| Salt Lake City, UT |

4.00 |

|

No data |

|

5.49 |

1.49 |

36 |

3.70 |

3.77 |

| San Antonio, TX |

3.69 |

4.43 |

0.74 |

2 |

4.41 |

0.72 |

15 |

2.89 |

2.86 |

| San Diego, CA |

7.98 |

10.72 |

2.74 |

42 |

10.65 |

2.67 |

48 |

6.88 |

6.94 |

| San Francisco-Oakland, CA |

8.67 |

18.01 |

9.33 |

52 |

11.93 |

3.26 |

51 |

7.96 |

7.29 |

| San Jose, CA |

9.09 |

15.28 |

6.19 |

51 |

14.08 |

5.00 |

53 |

7.80 |

8.24 |

| Seattle, WA |

5.27 |

8.77 |

3.50 |

46 |

7.02 |

1.74 |

39 |

4.55 |

5.00 |

| Tampa-St. Petersburg, FL |

3.87 |

4.86 |

0.98 |

4 |

4.74 |

0.87 |

17 |

2.85 |

3.65 |

| Tucson, AZ |

4.00 |

4.41 |

0.41 |

1 |

4.71 |

0.71 |

14 |

4.17 |

3.54 |

| Virginia Beach-Norfolk, VA-NC |

3.48 |

4.65 |

1.17 |

7 |

4.11 |

0.63 |

9 |

2.94 |

3.00 |

| Washington, DC-VA-MD-WV |

4.08 |

5.64 |

1.57 |

16 |

5.54 |

1.46 |

35 |

3.76 |

3.38 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Overall median multiple from Demographia International Housing Affordability Survey: Updated with revised income data from 2016 ACS. |

| Median multiple: Median house price divided by median household income |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Table 3 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| African-American Housing Affordability Gap Ranked: Most to Least Equal |

| 53 Major Metropolitan Areas (Over 1,000,000 Population) |

| Median Multiple (Median house price divided by median household income) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| MSA |

Median Multiple: All Households |

Median Multiple: African-American |

African American Housing Affordability Gap in Years |

Ranked Most to Least Equal: African-American |

Median Multiple:

Hispanic |

Hispanic Housing Affordability Gap in Years |

Ranked Most to Least Equal: Hispanic |

Exhibit: Median Multiple: Asian |

Exhibit: Median Multiple: White Non-Hispanic |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Tucson, AZ |

4.00 |

4.41 |

0.41 |

1 |

4.71 |

0.71 |

14 |

4.17 |

3.54 |

| San Antonio, TX |

3.69 |

4.43 |

0.74 |

2 |

4.41 |

0.72 |

15 |

2.89 |

2.86 |

| Atlanta, GA |

2.95 |

3.83 |

0.88 |

3 |

3.65 |

0.70 |

13 |

2.30 |

2.45 |

| Tampa-St. Petersburg, FL |

3.87 |

4.86 |

0.98 |

4 |

4.74 |

0.87 |

17 |

2.85 |

3.65 |

| Houston, TX |

3.52 |

4.57 |

1.05 |

5 |

4.68 |

1.15 |

27 |

2.54 |

2.65 |

| Riverside-San Bernardino, CA |

5.38 |

6.55 |

1.16 |

6 |

6.04 |

0.66 |

11 |

4.04 |

4.85 |

| Virginia Beach-Norfolk, VA-NC |

3.48 |

4.65 |

1.17 |

7 |

4.11 |

0.63 |

9 |

2.94 |

3.00 |

| Memphis, TN-MS-AR |

3.12 |

4.37 |

1.25 |

8 |

3.68 |

0.56 |

8 |

2.13 |

2.29 |

| Dallas-Fort Worth, TX |

3.56 |

4.98 |

1.42 |

9 |

4.70 |

1.14 |

26 |

2.55 |

2.87 |

| Birmingham, AL |

3.57 |

4.99 |

1.42 |

10 |

3.96 |

0.39 |

4 |

2.95 |

3.02 |

| Jacksonville, FL |

3.71 |

5.15 |

1.43 |

11 |

3.88 |

0.16 |

2 |

3.32 |

3.38 |

| Baltimore, MD |

3.29 |

4.75 |

1.46 |

12 |

3.64 |

0.34 |

3 |

2.60 |

2.83 |

| Charlotte, NC-SC |

3.47 |

4.95 |

1.47 |

13 |

4.77 |

1.30 |

32 |

2.31 |

3.08 |

| Phoenix, AZ |

4.01 |

5.54 |

1.53 |

14 |

5.07 |

1.06 |

25 |

3.17 |

3.62 |

| Raleigh, NC |

3.46 |

5.01 |

1.56 |

15 |

5.59 |

2.13 |

44 |

2.47 |

3.12 |

| Washington, DC-VA-MD-WV |

4.08 |

5.64 |

1.57 |

16 |

5.54 |

1.46 |

35 |

3.76 |

3.38 |

| Miami, FL |

5.94 |

7.58 |

1.64 |

17 |

6.64 |

0.70 |

12 |

4.39 |

4.68 |

| Nashville, TN |

3.74 |

5.43 |

1.69 |

18 |

5.04 |

1.30 |

33 |

3.12 |

3.43 |

| Austin, TX |

4.00 |

5.69 |

1.69 |

19 |

5.04 |

1.04 |

24 |

3.23 |

3.52 |

| Hartford, CT |

3.18 |

4.88 |

1.70 |

20 |

5.48 |

2.29 |

47 |

2.78 |

2.82 |

| Richmond, VA |

3.74 |

5.44 |

1.70 |

21 |

4.61 |

0.87 |

18 |

2.75 |

3.14 |

| Orlando, FL |

4.28 |

6.00 |

1.72 |

22 |

5.21 |

0.94 |

22 |

2.93 |

3.60 |

| St. Louis,, MO-IL |

2.74 |

4.46 |

1.72 |

23 |

3.15 |

0.41 |

5 |

2.41 |

2.45 |

| Columbus, OH |

2.91 |

4.78 |

1.87 |

24 |

4.10 |

1.19 |

30 |

2.50 |

2.68 |

| Louisville, KY-IN |

2.99 |

4.90 |

1.91 |

25 |

3.92 |

0.93 |

21 |

2.48 |

2.71 |

| Pittsburgh, PA |

2.68 |

4.61 |

1.93 |

26 |

2.70 |

0.02 |

1 |

1.97 |

2.54 |

| Cleveland, OH |

2.54 |

4.50 |

1.96 |

27 |

3.17 |

0.63 |

10 |

1.49 |

2.16 |

| Grand Rapids, MI |

2.68 |

4.66 |

1.98 |

28 |

3.85 |

1.16 |

28 |

2.95 |

2.53 |

| Las Vegas, NV |

4.37 |

6.36 |

1.98 |

29 |

5.19 |

0.82 |

16 |

3.63 |

3.85 |

| Kansas City, MO-KS |

2.95 |

4.96 |

2.00 |

30 |

3.97 |

1.02 |

23 |

2.64 |

2.68 |

| Indianapolis. IN |

2.82 |

4.89 |

2.07 |

31 |

4.45 |

1.63 |

38 |

2.48 |

2.50 |

| Oklahoma City, OK |

2.74 |

4.81 |

2.07 |

32 |

3.62 |

0.88 |

19 |

2.52 |

2.45 |

| Rochester, NY |

2.42 |

4.52 |

2.10 |

33 |

4.67 |

2.25 |

46 |

2.26 |

2.21 |

| Providence, RI-MA |

4.26 |

6.38 |

2.12 |

34 |

7.21 |

2.95 |

50 |

3.09 |

3.95 |

| Cincinnati, OH-KY-IN |

2.53 |

4.70 |

2.17 |

35 |

2.99 |

0.46 |

6 |

1.75 |

2.33 |

| Philadelphia, PA-NJ-DE-MD |

3.42 |

5.69 |

2.28 |

36 |

5.59 |

2.17 |

45 |

3.02 |

2.82 |

| Denver, CO |

5.34 |

7.64 |

2.29 |

37 |

7.40 |

2.05 |

42 |

5.33 |

4.76 |

| Buffalo, NY |

2.48 |

4.79 |

2.32 |

38 |

4.58 |

2.10 |

43 |

2.90 |

2.20 |

| New York, NY-NJ-PA |

5.40 |

7.85 |

2.45 |

39 |

8.22 |

2.82 |

49 |

4.68 |

4.25 |

| New Orleans. LA |

3.85 |

6.42 |

2.57 |

40 |

5.02 |

1.17 |

29 |

4.01 |

2.93 |

| Detroit, MI |

4.01 |

6.71 |

2.70 |

41 |

4.53 |

0.52 |

7 |

2.56 |

3.48 |

| San Diego, CA |

7.98 |

10.72 |

2.74 |

42 |

10.65 |

2.67 |

48 |

6.88 |

6.94 |

| Chicago, IL-IN-WI |

3.56 |

6.30 |

2.75 |

43 |

4.45 |

0.90 |

20 |

2.69 |

2.94 |

| Sacramento, CA |

5.00 |

7.81 |

2.81 |

44 |

6.21 |

1.21 |

31 |

4.63 |

4.46 |

| Los Angeles, CA |

7.69 |

11.15 |

3.46 |

45 |

9.74 |

2.05 |

41 |

6.68 |

6.03 |

| Seattle, WA |

5.27 |

8.77 |

3.50 |

46 |

7.02 |

1.74 |

39 |

4.55 |

5.00 |

| Boston, MA-NH |

5.11 |

8.69 |

3.58 |

47 |

9.02 |

3.90 |

52 |

4.67 |

4.62 |

| Minneapolis-St. Paul, MN-WI |

3.24 |

6.83 |

3.59 |

48 |

4.64 |

1.40 |

34 |

3.25 |

3.01 |

| Milwaukee,WI |

3.93 |

7.88 |

3.95 |

49 |

5.79 |

1.86 |

40 |

2.78 |

3.33 |

| Portland, OR-WA |

5.11 |

9.38 |

4.26 |

50 |

6.69 |

1.57 |

37 |

4.44 |

4.89 |

| San Jose, CA |

9.09 |

15.28 |

6.19 |

51 |

14.08 |

5.00 |

53 |

7.80 |

8.24 |

| San Francisco-Oakland, CA |

8.67 |

18.01 |

9.33 |

52 |

11.93 |

3.26 |

51 |

7.96 |

7.29 |

| Salt Lake City, UT |

4.00 |

|

No data |

|

5.49 |

1.49 |

36 |

3.70 |

3.77 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Overall median multiple from Demographia International Housing Affordability Survey: Updated with revised income data from 2016 ACS. |

| Median multiple: Median house price divided by median household income |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Table 4 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Hispanic Housing Affordability Gap Ranked: Most to Least Equal |

| 53 Major Metropolitan Areas (Over 1,000,000 Population) |

| Median Multiple (Median house price divided by median household income) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| MSA |

Median Multiple: All Households |

Median Multiple: African-American |

African American Housing Affordability Gap in Years |

Ranked Most to Least Equal: African-American |

Median Multiple:

Hispanic |

Hispanic Housing Affordability Gap in Years |

Ranked Most to Least Equal: Hispanic |

Exhibit: Median Multiple: Asian |

Exhibit: Median Multiple: White Non-Hispanic |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Pittsburgh, PA |

2.68 |

4.61 |

1.93 |

26 |

2.70 |

0.02 |

1 |

1.97 |

2.54 |

| Jacksonville, FL |

3.71 |

5.15 |

1.43 |

11 |

3.88 |

0.16 |

2 |

3.32 |

3.38 |

| Baltimore, MD |

3.29 |

4.75 |

1.46 |

12 |

3.64 |

0.34 |

3 |

2.60 |

2.83 |

| Birmingham, AL |

3.57 |

4.99 |

1.42 |

10 |

3.96 |

0.39 |

4 |

2.95 |

3.02 |

| St. Louis,, MO-IL |

2.74 |

4.46 |

1.72 |

23 |

3.15 |

0.41 |

5 |

2.41 |

2.45 |

| Cincinnati, OH-KY-IN |

2.53 |

4.70 |

2.17 |

35 |

2.99 |

0.46 |

6 |

1.75 |

2.33 |

| Detroit, MI |

4.01 |

6.71 |

2.70 |

41 |

4.53 |

0.52 |

7 |

2.56 |

3.48 |

| Memphis, TN-MS-AR |

3.12 |

4.37 |

1.25 |

8 |

3.68 |

0.56 |

8 |

2.13 |

2.29 |

| Virginia Beach-Norfolk, VA-NC |

3.48 |

4.65 |

1.17 |

7 |

4.11 |

0.63 |

9 |

2.94 |

3.00 |

| Cleveland, OH |

2.54 |

4.50 |

1.96 |

27 |

3.17 |

0.63 |

10 |

1.49 |

2.16 |

| Riverside-San Bernardino, CA |

5.38 |

6.55 |

1.16 |

6 |

6.04 |

0.66 |

11 |

4.04 |

4.85 |

| Miami, FL |

5.94 |

7.58 |

1.64 |

17 |

6.64 |

0.70 |

12 |

4.39 |

4.68 |

| Atlanta, GA |

2.95 |

3.83 |

0.88 |

3 |

3.65 |

0.70 |

13 |

2.30 |

2.45 |

| Tucson, AZ |

4.00 |

4.41 |

0.41 |

1 |

4.71 |

0.71 |

14 |

4.17 |

3.54 |

| San Antonio, TX |

3.69 |

4.43 |

0.74 |

2 |

4.41 |

0.72 |

15 |

2.89 |

2.86 |

| Las Vegas, NV |

4.37 |

6.36 |

1.98 |

29 |

5.19 |

0.82 |

16 |

3.63 |

3.85 |

| Tampa-St. Petersburg, FL |

3.87 |

4.86 |

0.98 |

4 |

4.74 |

0.87 |

17 |

2.85 |

3.65 |

| Richmond, VA |

3.74 |

5.44 |

1.70 |

21 |

4.61 |

0.87 |

18 |

2.75 |

3.14 |

| Oklahoma City, OK |

2.74 |

4.81 |

2.07 |

32 |

3.62 |

0.88 |

19 |

2.52 |

2.45 |

| Chicago, IL-IN-WI |

3.56 |

6.30 |

2.75 |

43 |

4.45 |

0.90 |

20 |

2.69 |

2.94 |

| Louisville, KY-IN |

2.99 |

4.90 |

1.91 |

25 |

3.92 |

0.93 |

21 |

2.48 |

2.71 |

| Orlando, FL |

4.28 |

6.00 |

1.72 |

22 |

5.21 |

0.94 |

22 |

2.93 |

3.60 |

| Kansas City, MO-KS |

2.95 |

4.96 |

2.00 |

30 |

3.97 |

1.02 |

23 |

2.64 |

2.68 |

| Austin, TX |

4.00 |

5.69 |

1.69 |

19 |

5.04 |

1.04 |

24 |

3.23 |

3.52 |

| Phoenix, AZ |

4.01 |

5.54 |

1.53 |

14 |

5.07 |

1.06 |

25 |

3.17 |

3.62 |

| Dallas-Fort Worth, TX |

3.56 |

4.98 |

1.42 |

9 |

4.70 |

1.14 |

26 |

2.55 |

2.87 |

| Houston, TX |

3.52 |

4.57 |

1.05 |

5 |

4.68 |

1.15 |

27 |

2.54 |

2.65 |

| Grand Rapids, MI |

2.68 |

4.66 |

1.98 |

28 |

3.85 |

1.16 |

28 |

2.95 |

2.53 |

| New Orleans. LA |

3.85 |

6.42 |

2.57 |

40 |

5.02 |

1.17 |

29 |

4.01 |

2.93 |

| Columbus, OH |

2.91 |

4.78 |

1.87 |

24 |

4.10 |

1.19 |

30 |

2.50 |

2.68 |

| Sacramento, CA |

5.00 |

7.81 |

2.81 |

44 |

6.21 |

1.21 |

31 |

4.63 |

4.46 |

| Charlotte, NC-SC |

3.47 |

4.95 |

1.47 |

13 |

4.77 |

1.30 |

32 |

2.31 |

3.08 |

| Nashville, TN |

3.74 |

5.43 |

1.69 |

18 |

5.04 |

1.30 |

33 |

3.12 |

3.43 |

| Minneapolis-St. Paul, MN-WI |

3.24 |

6.83 |

3.59 |

48 |

4.64 |

1.40 |

34 |

3.25 |

3.01 |

| Washington, DC-VA-MD-WV |

4.08 |

5.64 |

1.57 |

16 |

5.54 |

1.46 |

35 |

3.76 |

3.38 |

| Salt Lake City, UT |

4.00 |

|

No data |

|

5.49 |

1.49 |

36 |

3.70 |

3.77 |

| Portland, OR-WA |

5.11 |

9.38 |

4.26 |

50 |

6.69 |

1.57 |

37 |

4.44 |

4.89 |

| Indianapolis. IN |

2.82 |

4.89 |

2.07 |

31 |

4.45 |

1.63 |

38 |

2.48 |

2.50 |

| Seattle, WA |

5.27 |

8.77 |

3.50 |

46 |

7.02 |

1.74 |

39 |

4.55 |

5.00 |

| Milwaukee,WI |

3.93 |

7.88 |

3.95 |

49 |

5.79 |

1.86 |

40 |

2.78 |

3.33 |

| Los Angeles, CA |

7.69 |

11.15 |

3.46 |

45 |

9.74 |

2.05 |

41 |

6.68 |

6.03 |

| Denver, CO |

5.34 |

7.64 |

2.29 |

37 |

7.40 |

2.05 |

42 |

5.33 |

4.76 |

| Buffalo, NY |

2.48 |

4.79 |

2.32 |

38 |

4.58 |

2.10 |

43 |

2.90 |

2.20 |

| Raleigh, NC |

3.46 |

5.01 |

1.56 |

15 |

5.59 |

2.13 |

44 |

2.47 |

3.12 |

| Philadelphia, PA-NJ-DE-MD |

3.42 |

5.69 |

2.28 |

36 |

5.59 |

2.17 |

45 |

3.02 |

2.82 |

| Rochester, NY |

2.42 |

4.52 |

2.10 |

33 |

4.67 |

2.25 |

46 |

2.26 |

2.21 |

| Hartford, CT |

3.18 |

4.88 |

1.70 |

20 |

5.48 |

2.29 |

47 |

2.78 |

2.82 |

| San Diego, CA |

7.98 |

10.72 |

2.74 |

42 |

10.65 |

2.67 |

48 |

6.88 |

6.94 |

| New York, NY-NJ-PA |

5.40 |

7.85 |

2.45 |

39 |

8.22 |

2.82 |

49 |

4.68 |

4.25 |

| Providence, RI-MA |

4.26 |

6.38 |

2.12 |

34 |

7.21 |

2.95 |

50 |

3.09 |

3.95 |

| San Francisco-Oakland, CA |

8.67 |

18.01 |

9.33 |

52 |

11.93 |

3.26 |

51 |

7.96 |

7.29 |

| Boston, MA-NH |

5.11 |

8.69 |

3.58 |

47 |

9.02 |

3.90 |

52 |

4.67 |

4.62 |

| San Jose, CA |

9.09 |

15.28 |

6.19 |

51 |

14.08 |

5.00 |

53 |

7.80 |

8.24 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Overall median multiple from Demographia International Housing Affordability Survey: Updated with revised income data from 2016 ACS. |

| Median multiple: Median house price divided by median household income |

Photograph: San Francisco Bay Area: Where metropolitan housing opportunity is most unequal

https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/archive/d/dc/200609291846…