Portland Metro’s president, David Bragdon, recently resigned to take a position with New York’s Bloomberg administration. Bragdon was nearing the end of his second elected term and ineligible for another term. Metro is the three county (Clackamas, Multnomah and Washington counties) planning agency that oversees Portland’s land use planning and transportation policies, among the most stringent and pro-transit in the nation.

Metro’s jurisdiction includes most of the bi-state (Washington and Oregon) Portland area metropolitan area, which also includes the core municipality of Portland and the core Multnomah County.

Local television station KGW (Channel 8) featured Bragdon in its Straight Talk program before he left Portland. Some of his comments may have been surprising, such as his strong criticism of the two state (Washington and Oregon) planning effort to replace the aging Interstate Bridge (I-5) and even more so, his comments on job creation in Portland. He noted “alarming trends below the surface,” including the failure to create jobs in the core of Portland “for a long time.”

Bragdon was on to something. Metro’s three county area suffers growing competitive difficulties, even in contrast to the larger metropolitan area (which includes Clark and Skamania counties in Washington, along with Yamhill and Columbia counties in Oregon). This is despite the fact that one of the most important objectives of Metro’s land use and transportation policies is to strengthen the urban core and to discourage suburbanization (a phenomenon urban planning theologians call “sprawl”).

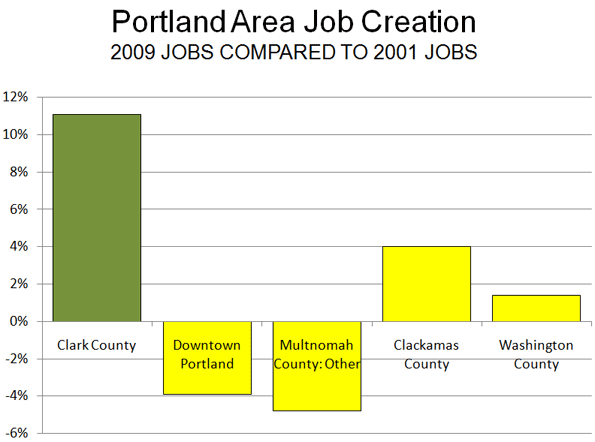

Anemic Job Creation: Jobs have simply not been created in Portland’s core. Since 2001, downtown employment has declined by 3,000 jobs, according to the Portland Business Alliance. In Multnomah County, Portland’s urban core and close-by surrounding communities, 20,000 jobs were lost between 2001 and 2009. Even during the prosperous years of 2000 to 2006, Multnomah County lost jobs. Suburban Washington and Clackamas counties gained jobs, but their contribution fell 12,000 jobs short of making up for Multnomah County’s loss. The real story has been Clark County (the county seat is Vancouver), across the I-5 Interstate Bridge in neighboring Washington and outside Metro’s jurisdiction. Clark County generated 13,000 net new jobs between 2001 and 2009 (Figure 1).

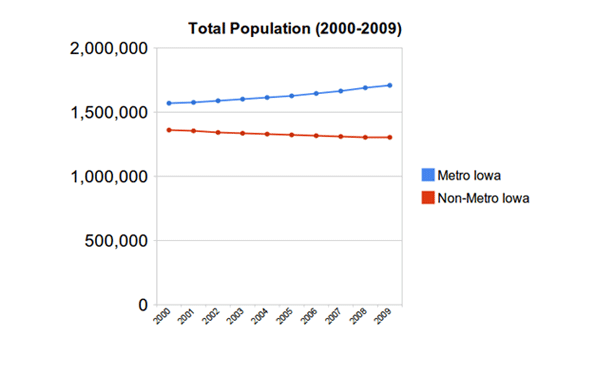

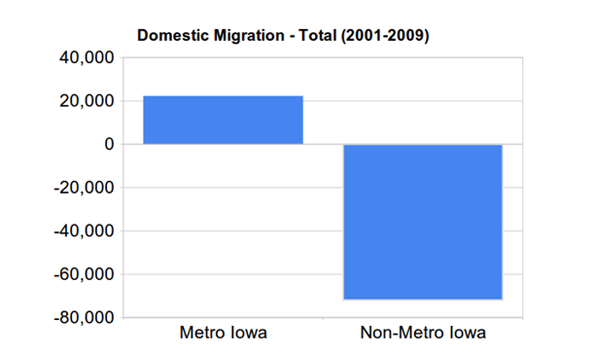

Domestic Migration: Not only are companies not creating jobs in the three county area, but people are choosing to locate in other parts of the metropolitan area.

Between 2000 and 2009, the three counties – roughly 75% of the region’s total population in 2000 – attracted just one-half of net domestic migration into the metropolitan area. Washington’s suburban Clark County, across the Interstate Bridge, added a net 48,000 by domestic migration and has accounted for 40% of the metropolitan area’s figure all by itself.

Core Multnomah County, which had nearly double Clark County’s 2000 population, added only 4,000 net domestic migrants, at a rate less than 1/20th that of Clark County. Suburban Clackamas and Washington counties did better, but between them achieved barely one-half of the Clark County rate.

Exurban Columbia and Yamhill counties, outside the jurisdiction of Metro but inside the metropolitan area, added nearly 13,000 domestic migrants, more than three times that of Multnomah County, despite their combined population less than one-fifth that of Multnomah’s in 2000.

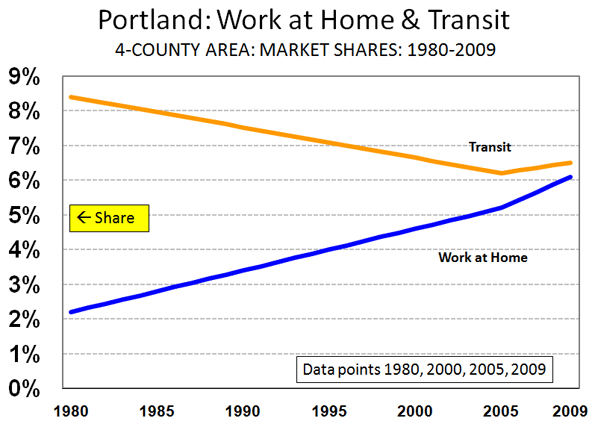

Effects of Pro-Transit Policies: Portland’s unintended decentralization has even damaged the much promoted, and subsidized, public transit agencies. Despite Portland’s pro-transit policies, the three county transit work trip market share fell from 9.7% in 1980, before the first light rail line was opened, to 7.4% in 2000, after two light rail lines had opened. Two more light rail lines and 9 years later, (2009) the three county transit work trip market share had fallen to 7.4%, despite the boost of higher gasoline prices. The three county transit work trip market share loss from 9.7% in 1980 to 7.4% in 2009 calculates to a near one-quarter market share loss. By contrast, Seattle’s three county metropolitan area, without light rail until 2009, experienced a 5% increase in transit work trip market share from 1980 to 2009 (8.3% to 8.7%).

While taxpayer funded transit was attracting less than its share of new commuters out of cars, one mode –unsupported by public funds – was doing very well. Between 1980 and 2009, working at home rose from 2.2% of employment to 6.2%. in the four county area (including Clark County). Thus, nearly as many people worked at home as rode transit to work in 2009 (Note). Already, working at home accounts for a larger share of employment than transit in the larger 7 county metropolitan area. All of this is despite Portland’s having spent an extra $5 billion on transit in the last 25 years on light rail expansions and more bus service. (Figure 2).

Why is the Three County Area Doing Less Well? Why have Portland’s policies that are designed to help the core failed to draw jobs and people? People who move to the Portland area from other parts of the nation are probably drawn by the lower house prices in Clark County, where less stringent land use regulation has kept houses more affordable. New housing in Clark County is also built on average sized lots, rather than the much smaller lots that have been required by Metro’s land use policies. House prices are also lower in the exurban counties outside Metro’s jurisdiction.

As Metro has forced urban densities up in the three county area and failed to provide sufficient new roadway capacity, traffic congestion has become much worse. A long segment of Interstate 5 in north Portland seems in a perpetual peak hour gridlock unusual for a medium sized metropolitan area, which is obvious from Google traffic maps that show average conditions by time and day of week. Even more unusual is the gridlock on a long stretch of the US-26 Sunset Highway that serves the suburban Silicon Forest of Washington County. A long overdue expansion will soon provide some relief on US-26. However transportation officials seem in no hurry to provide the additional capacity necessary to reduce both greenhouse gas emissions and excessive travel delays on Interstate 5 in north Portland. People who move to Clark or the exurban counties can avoid these bottlenecks by working closer to home or even in the periphery of the three county area.

Portland has important competitive advantages, such as a temperate climate and marvelous scenery. It also helps to be close to hyper- uncompetitive California, which keeps exporting households to neighboring states. But a higher cost of living driven by policies that have kept prices 40% higher than before the housing bubble (adjusted for household incomes), and increasing traffic congestion make Portland’s three county area less competitive and nearby alternatives more attractive.

This is not surprising. More intense regulation deters business attraction and expansion. An economic study by Raven Saks of the Federal Reserve Board concluded that … metropolitan areas with stringent development regulations generate less employment growth. At least part of the reason the Metro region’s diminished competitiveness lies with a failed strategy that appears to be having the exact opposite effect to what has been advertised – and widely celebrated – among planners from coast to coast.

Note: 1980 three county data not available on-line.

Wendell Cox is a Visiting Professor, Conservatoire National des Arts et Metiers, Paris and the author of “War on the Dream: How Anti-Sprawl Policy Threatens the Quality of Life”

Photograph: South Waterfront Condominiums, Portland. Photo by author