The human world is fast becoming an urban world — and according to many, the faster that happens and the bigger the cities get, the better off we all will be. The old suburban model, with families enjoying their own space in detached houses, is increasingly behind us; we’re heading toward heavier reliance on public transit, greater density, and far less personal space. Global cities, even colossal ones like Mumbai and Mexico City, represent our cosmopolitan future, we’re now told; they will be nerve centers of international commerce and technological innovation just like the great metropolises of the past — only with the Internet and smart phones.

According to Columbia University’s Saskia Sassen, megacities will inevitably occupy what Vladimir Lenin called the “commanding heights” of the global economy, though instead of making things they’ll apparently be specializing in high-end “producer services” — advertising, law, accounting, and so forth — for worldwide clients. Other scholars, such as Harvard University’s Edward Glaeser, envision universities helping to power the new “skilled city,” where high wages and social amenities attract enough talent to enable even higher-cost urban meccas to compete.

The theory goes beyond established Western cities. A recent World Bank report on global megacities insists that when it comes to spurring economic growth, denser is better: “To try to spread out economic activity,” the report argues, is to snuff it. Historian Peter Hall seems to be speaking for a whole generation of urbanists when he argues that we are on the cusp of a “coming golden age” of great cities.

The only problem is, these predictions may not be accurate. Yes, the percentage of people living in cities is clearly growing. In 1975, Tokyo was the largest city in the world, with over 26 million residents, and there were only two other cities worldwide with more than 10 million residents. By 2025, the U.N. projects that there may be 27 cities of that size. The proportion of the world’s population living in cities, which has already shot up from 14 percent in 1900 to about 50 percent in 2008, could be 70 percent by 2050. But here’s what the boosters don’t tell you: It’s far less clear whether the extreme centralization and concentration advocated by these new urban utopians is inevitable — and it’s not at all clear that it’s desirable.

Not all Global Cities are created equal. We can hope the developing-world metropolises of the future will look a lot like the developed-world cities of today, just much, much larger — but that’s not likely to be the case. Today’s Third World megacities face basic challenges in feeding their people, getting them to and from work, and maintaining a minimum level of health. In some, like Mumbai, life expectancy is now at least seven years less than the country as a whole. And many of the world’s largest advanced cities are nestled in relatively declining economies — London, Los Angeles, New York, Tokyo. All suffer growing income inequality and outward migration of middle-class families. Even in the best of circumstances, the new age of the megacity might well be an era of unparalleled human congestion and gross inequality.

Perhaps we need to consider another approach. As unfashionable as it might sound, what if we thought less about the benefits of urban density and more about the many possibilities for proliferating more human-scaled urban centers; what if healthy growth turns out to be best achieved through dispersion, not concentration? Instead of overcrowded cities rimmed by hellish new slums, imagine a world filled with vibrant smaller cities, suburbs, and towns: Which do you think is likelier to produce a higher quality of life, a cleaner environment, and a lifestyle conducive to creative thinking?

So how do we get there? First, we need to dismantle some common urban legends.

Perhaps the most damaging misconception of all is the idea that concentration by its very nature creates wealth. Many writers, led by popular theorist Richard Florida, argue that centralized urban areas provide broader cultural opportunities and better access to technology, attracting more innovative, plugged-in people (Florida’s “creative class“) who will in the long term produce greater economic vibrancy. The hipper the city, the mantra goes, the richer and more successful it will be — and a number of declining American industrial hubs have tried to rebrand themselves as “creative class” hot spots accordingly.

But this argument, or at least many applications of it, gets things backward. Arts and culture generally do not fuel economic growth by themselves; rather, economic growth tends to create the preconditions for their development. Ancient Athens and Rome didn’t start out as undiscovered artist neighborhoods. They were metropolises built on imperial wealth — largely collected by force from their colonies — that funded a new class of patrons and consumers of the arts. Renaissance Florence and Amsterdam established themselves as trade centers first and only then began to nurture great artists from their own middle classes and the surrounding regions.

Even modern Los Angeles owes its initial ascendancy as much to agriculture and oil as to Hollywood. Today, its port and related industries employ far more people than the entertainment business does. (In any case, the men who built Hollywood were hardly cultured aesthetes by middle-class American standards; they were furriers, butchers, and petty traders, mostly from hardscrabble backgrounds in the czarist shtetls and back streets of America’s tough ethnic ghettos.) New York, now arguably the world’s cultural capital, was once dismissed as a boorish, money-obsessed town, much like the contemporary urban critique of Dallas, Houston, or Phoenix.

Sadly, cities desperate to reverse their slides have been quick to buy into the simplistic idea that by merely branding themselves “creative” they can renew their dying economies; think of Cleveland’s Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, Michigan’s bid to market Detroit as a “cool city,” and similar efforts in the washed-up industrial towns of the British north. Being told you live in a “European Capital of Culture,” as Liverpool was in 2008, means little when your city has no jobs and people are leaving by the busload.

Even legitimate cultural meccas aren’t insulated from economic turmoil. Berlin — beloved by writers, artists, tourists, and romantic expatriates — has cultural institutions that would put any wannabe European Capital of Culture to shame, as well as a thriving underground art and music scene. Yet for all its bohemian spirit, Berlin is also deeply in debt and suffers from unemployment far higher than Germany’s national average, with rates reaching 14 percent. A full quarter of its workers, many of them living in wretched immigrant ghettos, earn less than 900 euros a month; compare that with Frankfurt, a smaller city more known for its skyscrapers and airport terminals than for any major cultural output, but which boasts one of Germany’s lowest unemployment rates and by some estimates the highest per capita income of any European city. No wonder Berlin Mayor Klaus Wowereit once described his city as “poor but sexy.”

Culture, media, and other “creative” industries, important as they are for a city’s continued prosperity, simply do not spark an economy on their own. It turns out to be the comparatively boring, old-fashioned industries, such as trade in goods, manufacturing, energy, and agriculture, that drive the world’s fastest-rising cities. In the 1960s and 1970s, the industrial capitals of Seoul and Tokyo developed their economies far faster than Cairo and Jakarta, which never created advanced industrial bases. China’s great coastal urban centers, notably Guangzhou, Shanghai, and Shenzhen, are replicating this pattern with big business in steel, textiles, garments, and electronics, and the country’s vast interior is now poised to repeat it once again. Fossil fuels — not art galleries — have powered the growth of several of the world’s fastest-rising urban areas, including Abu Dhabi, Houston, Moscow, and Perth.

It’s only after urban centers achieve economic success that they tend to look toward the higher-end amenities the creative-classers love. When Abu Dhabi decided to import its fancy Guggenheim and Louvre satellite museums, it was already, according to Fortune magazine, the world’s richest city. Beijing, Houston, Shanghai, and Singapore are opening or expanding schools for the arts, museums, and gallery districts. But they paid for them the old-fashioned way.

Nor is the much-vaunted “urban core” the only game in town. Innovators of all kinds seek to avoid the high property prices, overcrowding, and often harsh anti-business climates of the city center. Britain’s recent strides in technology and design-led manufacturing have been concentrated not in London, but along the outer reaches of the Thames Valley and the areas around Cambridge. It’s the same story in continental Europe, from the exurban Grand-Couronne outside of Paris to the “edge cities” that have sprung up around Amsterdam and Rotterdam. In India, the bulk of new tech companies cluster in campus-like developments around — but not necessarily in — Bangalore, Hyderabad, and New Delhi. And let’s not forget that Silicon Valley, the granddaddy of global tech centers and still home to the world’s largest concentration of high-tech workers, remains essentially a vast suburb. Apple, Google, and Intel don’t seem to mind. Those relative few who choose to live in San Francisco can always take the company-provided bus.

In fact, the suburbs are not as terrible as urban boosters frequently insist.

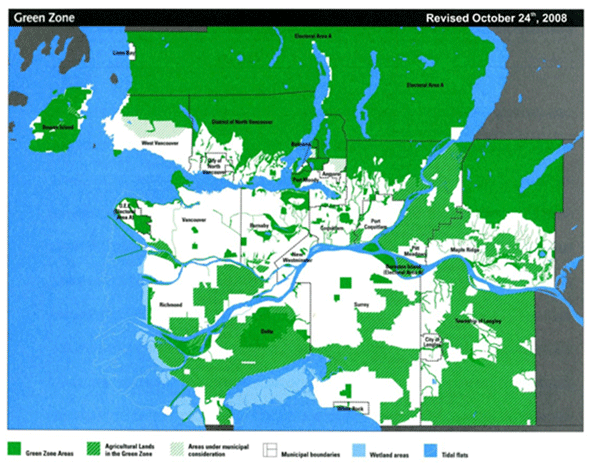

Consider the environment. We tend to associate suburbia with carbon dioxide-producing sprawl and urban areas with sustainability and green living. But though it’s true that urban residents use less gas to get to work than their suburban or rural counterparts, when it comes to overall energy use the picture gets more complicated. Studies in Australia and Spain have found that when you factor in apartment common areas, second residences, consumption, and air travel, urban residents can easily use more energy than their less densely packed neighbors. Moreover, studies around the world — from Beijing and Rome to London and Vancouver — have found that packed concentrations of concrete, asphalt, steel, and glass produce what are known as “heat islands,” generating 6 to 10 degrees Celsius more heat than surrounding areas and extending as far as twice a city’s political boundaries.

When it comes to inequality, cities might even be the problem. In the West, the largest cities today also tend to suffer the most extreme polarization of incomes. In 1980, Manhattan ranked 17th among U.S. counties for income disparity; by 2007 it was first, with the top fifth of wage earners earning 52 times what the bottom fifth earned. In Toronto between 1970 and 2001, according to one recent study, middle-income neighborhoods shrank by half, dropping from two-thirds of the city to one-third, while poor districts more than doubled to 40 percent. By 2020, middle-class neighborhoods could fall to about 10 percent.

Cities often offer a raw deal for the working class, which ends up squeezed by a lethal combination of chronically high housing costs and chronically low opportunity in economies dominated by finance and other elite industries. Once the cost of living is factored in, more than half the children in inner London live in poverty, the highest level in Britain, according to a Greater London Authority study. More than 1 million Londoners were on public support in 2002, in a city of roughly 8 million.

The disparities are even starker in Asia. Shenzhen and Hong Kong, for instance, have among the most skewed income distributions in the region. A relatively small number of skilled professionals and investors are doing very well, yet millions are migrating to urban slums in places like Mumbai not because they’ve all suddenly become “knowledge workers,” but because of the changing economics of farming. And by the way, Mumbai’s slums are still expanding as a proportion of the city’s overall population — even as India’s nationwide poverty rate has fallen from one in three Indians to one in five over the last two decades. Forty years ago, slum dwellers accounted for one in six Mumbaikars. Now they are a majority.

To their credit, talented new urbanists have had moderate success in turning smaller cities like Chattanooga and Hamburg into marginally more pleasant places to live. But grandiose theorists, with their focus on footloose elites and telecommuting technogeniuses, have no practical answers for the real problems that plague places like Mumbai, let alone Cairo, Jakarta, Manila, Nairobi, or any other 21st-century megacity: rampant crime, crushing poverty, choking pollution. It’s time for a completely different approach, one that abandons the long-held assumption that scale and growth go hand in hand.

Throughout the long history of urban development, the size of a city roughly correlated with its wealth, standard of living, and political strength. The greatest and most powerful cities were almost always the largest in population: Babylon, Rome, Alexandria, Baghdad, Delhi, London, or New York.

But bigger might no longer mean better. The most advantaged city of the future could well turn out to be a much smaller one. Cities today are expanding at an unparalleled rate when it comes to size, but wealth, power, and general well-being lag behind. With the exception of Los Angeles, New York, and Tokyo, most cities of 10 million or more are relatively poor, with a low standard of living and little strategic influence. The cities that do have influence, modern infrastructure, and relatively high per capita income, by contrast, are often wealthy small cities like Abu Dhabi or hard-charging up-and-comers such as Singapore. Their efficient, agile economies can outpace lumbering megacities financially, while also maintaining a high quality of life. With almost 5 million residents, for example, Singapore isn’t at the top of the list in terms of population. But its GDP is much higher than that of larger cities like Cairo, Lagos, and Manila. Singapore boasts a per capita income of almost $50,000, one of the highest in the world, roughly the same as America’s or Norway’s. With one of the world’s three largest ports, a zippy and safe subway system, and an impressive skyline, Singapore is easily the cleanest, most efficient big city in all of Asia. Other smaller-scaled cities like Austin, Monterrey, and Tel Aviv have enjoyed similar success.

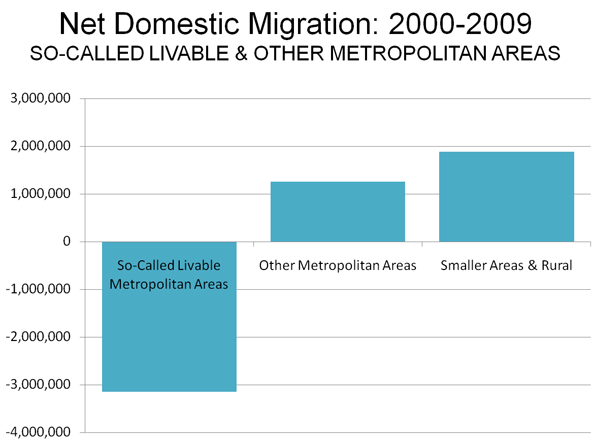

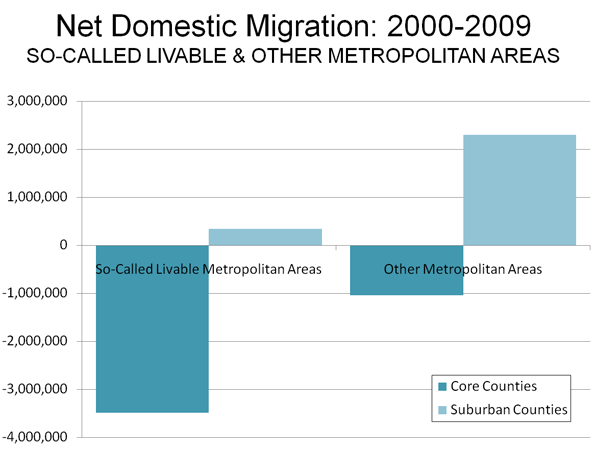

It turns out that the rise of the megacity is by no means inevitable — and it might not even be happening. Shlomo Angel, an adjunct professor at New York University’s Wagner School, has demonstrated that as the world’s urban population exploded from 1960 to 2000, the percentage living in the 100 largest megacities actually declined from nearly 30 percent to closer to 25 percent. Even the widely cited 2009 World Bank report on megacities, a staunchly pro-urban document, acknowledges that as societies become wealthier, they inevitably begin to deconcentrate, with the middle classes moving to the periphery. Urban population densities have been on the decline since the 19th century, Angel notes, as people have sought out cheaper and more appealing homes beyond city limits. In fact, despite all the “back to the city” hype of the past decade, more than 80 percent of new metropolitan growth in the United States since 2000 has been in suburbs.

And that’s not such a bad thing. Ultimately, dispersion — both city to suburb and megacity to small city — holds out some intriguing solutions to current urban problems. The idea took hold during the initial golden age of industrial growth — the English 19th century — when suburban “garden cities” were established around London’s borders. The great early 20th-century visionary Ebenezer Howard saw this as a means to create a “new civilization” superior to the crowded, dirty, and congested cities of his day. It was an ideal that attracted a wide range of thinkers, including Friedrich Engels and H.G. Wells.

More recently, a network of smaller cities in the Netherlands has helped create a smartly distributed national economy. Amsterdam, for example, has low-density areas between its core and its corporate centers. It has kept the great Dutch city both livable and competitive. American urbanists are trying to bring the same thinking to the United States. Delore Zimmerman, of the North Dakota-based Praxis Strategy Group, has helped foster high-tech-oriented development in small towns and cities from the Red River Valley in North Dakota and Minnesota to the Wenatchee region in Washington State. The outcome has been promising: Both areas are reviving from periods of economic and demographic decline.

But the dispersion model holds out even more hope for the developing world, where an alternative to megacities is an even more urgent necessity. Ashok R. Datar, chairman of the Mumbai Environmental Social Network and a longtime advisor to the Ambani corporate group, suggests that slowing migration to urban slums represents the most practical strategy for relieving Mumbai’s relentless poverty. His plan is similar to Zimmerman’s: By bolstering local industries, you can stanch the flow of job seekers to major city centers, maintaining a greater balance between rural areas and cities and avoiding the severe overcrowding that plagues Mumbai right now.

Between the 19th century, when Charles Dickens described London as a “sooty spectre” that haunted and deformed its inhabitants, and the present, something has been lost from our discussion of cities: the human element. The goal of urban planners should not be to fulfill their own grandiose visions of megacities on a hill, but to meet the needs of the people living in them, particularly those people suffering from overcrowding, environmental misery, and social inequality. When it comes to exporting our notions to the rest of the globe, we must be aware of our own susceptibility to fashionable theories in urban design — because while the West may be able to live with its mistakes, the developing world doesn’t enjoy that luxury.

This article originally appeared at Foreign Policy

Joel Kotkin is executive editor of NewGeography.com and is a distinguished presidential fellow in urban futures at Chapman University. He is author of The City: A Global History . His newest book is The Next Hundred Million: America in 2050

. His newest book is The Next Hundred Million: America in 2050 , released in February, 2010.

, released in February, 2010.

Photo: Mugley

In fact, much has changed. Religion in America is alive and well, but it’s different. Although Christian churches continue to dominate the religious landscape in the United States, there are new religious neighbors. Cultures and religious traditions that once existed “somewhere over there”, have moved beyond the large cities of the U.S. into the suburbs and exurbs, places where evangelical mega-churches have flourished for decades.

In fact, much has changed. Religion in America is alive and well, but it’s different. Although Christian churches continue to dominate the religious landscape in the United States, there are new religious neighbors. Cultures and religious traditions that once existed “somewhere over there”, have moved beyond the large cities of the U.S. into the suburbs and exurbs, places where evangelical mega-churches have flourished for decades.