The week opened with an important report on metropolitan demographics by the Brookings Institution, only to be followed by the Census Bureau’s annual report on migration, which contained a different message than the Brookings report. We offer yet a third analysis, since both the Brookings and the Census Bureau reports classify up to one-sixth of suburban population as not being in the suburbs.

Brookings: The new Brookings State of Metropolitan America report examined trends in the 100 largest metropolitan areas using Census Bureau data between 2000 and 2008 (the census and the American Community Survey). Brookings highlighted findings that some “primary cities” were experiencing an increase in white population, while the rest of the metropolitan area (which it called suburbs) was becoming more diverse. Not uncharacteristically, the core city oriented press took the bait and embellished a bit on the findings. MSNBC characterized the report as indicating that “many younger, educated whites move to cities for jobs and shorter commutes.” Brookings, which largely shares and encourages the urbanist media spin, calls this movement of young, educated whites from suburbs to the cities “bright flight.”

Brookings also expanded is previous finding that the majority of people in poverty live in suburbs to note that a majority of Hispanic and African-Americans now live in the suburbs. This is really not all that surprising, since suburban areas continue to grow faster and comprise the overwhelming share of metropolitan population.

Census Bureau: Just a day or two later, the Census Bureau published its annual analysis of migration in the nation. The basis of this report is the Current Population Survey, which like the American Community Survey is conducted by the Census Bureau. The Census Bureau report received considerably less press attention than the Brookings report, perhaps it would be hard to characterize any of its findings as being consistent with the favored “death of the suburbs” line. The previous annual editions back to the beginning of the decade indicate little difference from the 2008-2009 migration trends in the current report.

The Census Bureau analysis indicates that, almost regardless of the category, many more people are moving from “principal cities” to what it refers to as “suburbs.”

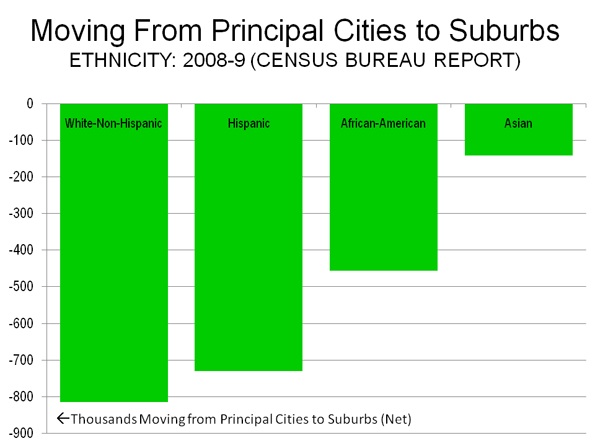

- Every ethnic group is moving to the suburbs in greater numbers than to principal cities. Three times as many Hispanics are moving from principal cities to the suburbs as from the suburbs to principal cities. The same is true for twice as many African-Americans and Asians. Whites are moving to the suburbs at 1.5 times the rate of their moving to principal cities (Figure 1).

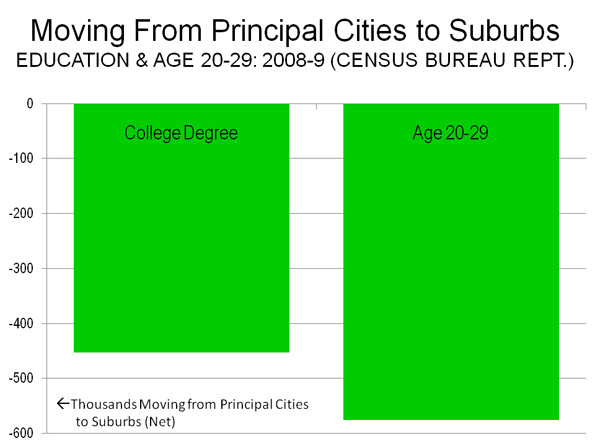

- Every age group but one is moving to the suburbs at substantially above the rate of movement to the principal cities. There is strong movement among people aged from 20 to 25 to the suburbs rather than the principal cities (Figure 2). The one exception was that among people over 85 years of age, not exactly the epitome of the “bright flight” cited by Brookings and the media.

- The overwhelming migration from principal cities to the suburbs, rather than from suburbs to principal cities was characteristic across all income categories.

- There is, in reality, little “bright flight” to report. Among people with college and graduate degrees, nearly twice as many moved from principal cities to suburbs as moved from suburbs to principal cities (Figure 2). While the Census report does not provide mobility information on educational attainment by age, there was strong movement of young adults to the suburbs (noted above).

The trends in the Census report are consistent with the domestic migration trends that we have previously reported.

What is a Suburb? There are significant problems with definition of the term “suburb in each of the reports.

The Office of Management and Budget (OMB), which establishes metropolitan area criteria switched to the “principal city” terminology for the 2000 census, partly to make it clear that principal cities were not inner cities or central cities. The criteria designates as principal cities, the largest in each metropolitan area, any city over 250,000 and any city with more than 50,000 population in which total employment exceeds the workforce.

Among the 52 major metropolitan areas (those with more than 1,000,000 population), OMB designates 230 principal cities. The Census Bureau report calls everything outside a principal city a suburb. In fact, most of the principal cities are themselves suburbs, developed since World War II as urban areas and expanded outward from their cores.

For example, principal city Schaumburg, Illinois is located well outside the core city of Chicago and contains a large suburban employment center (“edge city”). Bellevue, the large suburban employment center in the Seattle area is a principal city and not called a suburb by the Census Bureau. Cerritos, California is one of the 25 principal cities of the Los Angeles metropolitan area. Cerritos used to be called Dairy Valley, since it consisted largely of dairy farms until the middle 1950s.

The Brookings report, in recognition of this problem, calls its non-suburbs primary cities and limits them to no more than three for any metropolitan area. Still, many suburbs are designated as primary cities and not counted in the suburban data, such as Mesa, Arizona (Phoenix), Arlington, Texas (Dallas-Fort Worth), and Cary, North Carolina (Raleigh).

Suburban versus core analysis needs to be considerably more precise to be meaningful. It would be best to define the characteristics of the core and analyze metropolitan areas at the census tract level, rather than at the city level. However, the data at the city level is far more accessible and is thus predominantly used.

What is a Core City? Even so, it is important to recognize that there are substantial differences among core cities (which are, broadly speaking, the only parts of urban areas that are not suburbs). Core cities may be divided into three broad categories:

Pre-World War II Core Cities: These are core cities that have essentially the same boundaries as in 1950. There are 21 Pre-World War II Core Cities in the major metropolitan areas (See Table 2 below). These were largely built before the automobile became dominant, and once were predominately walking and transit cities. New York, Chicago, Boston, Philadelphia and San Francisco are probably the best examples.

Pre-World War II Core Cities with Suburbs: Many pre-World War II core cities either included wide swaths of vacant developable land in 1950 or annexed substantial amounts of vacant or suburban land after 1950. These cities have cores that are similar to the Pre-World War II Core Cities, but also include suburbs that are little different than the inner suburbs outside the city. For example, in 1950, Los Angeles contained substantial amounts of non-urban land in the San Fernando Valley, which was eventually covered with suburban development. Other cities, such as Milwaukee, Portland, Seattle, Austin and Houston annexed considerable suburban land after 1950. These annexations did not always result in increased population. For example, Salt Lake City doubled its land area between 1950 and 2000, yet retained essentially the same population. Milwaukee nearly doubled its land area, yet lost 40,000 residents.

Suburban Core Cities: A number of core cities developed predominantly after World War II and as a result, have little, if any pre-World War II core. The largest of these is Phoenix, which recently passed Philadelphia to become the nation’s 6th largest city. San Jose, Charlotte, Orlando and Las Vegas are also examples of Suburban Core Cities.

Another Perspective: The following analysis (expanded version available here) is offered to indicate general trends in suburbs when non-suburban areas are defined to exclude demonstrably suburban areas. (This may sound circular, but both Brookings and the Census Bureau define some suburban areas as non-suburban.)

| Table 1 | |||||

| Population Trends: Metropolitan Areas Over 1,000,000: 2000-2008 by Geography | |||||

|

2000

|

2008

|

Change

|

%

|

||

| Metropolitan Areas | 152,382,483 | 166,564,617 | 14,182,134 | 9.3% | |

| Core Cities | 43,818,674 | 45,922,606 | 2,103,932 | 4.8% | |

| Pre-WW2 Core Cities | 20,172,850 | 20,219,342 | 46,492 | 0.2% | |

| Pre-WW2 Core Cities with Suburbs | 18,472,298 | 19,723,295 | 1,250,997 | 6.8% | |

| Suburban Core Cities (Post WW2) | 5,173,526 | 5,979,969 | 806,443 | 15.6% | |

| Suburbs | 108,563,809 | 120,642,011 | 12,078,202 | 11.1% | |

| Suburbs Classified by OMB as Principal Cities | 17,968,287 | 19,334,689 | 1,366,402 | 7.6% | |

| Suburbs Not Classified as Principal Cities | 90,595,522 | 101,307,322 | 10,711,800 | 11.8% | |

| Calculated from US Bureau of the Census Data | |||||

| For classification of core cities, see Table 3 | |||||

| 2008 Population of "Suburbs Classified as Principal Cities" is slightly understated because there are no late official estimates for 7 "census designated places." (which are not cities): 2000 estimates used. | |||||

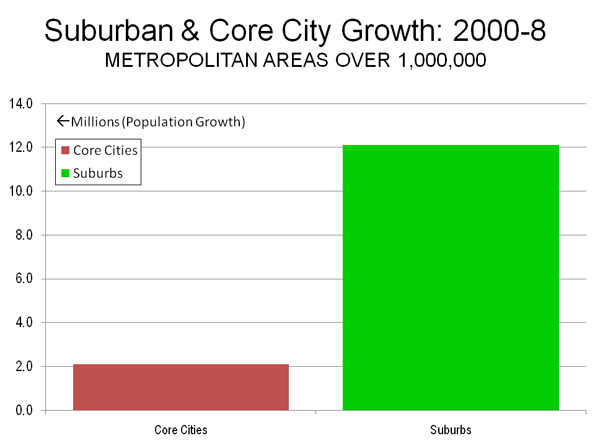

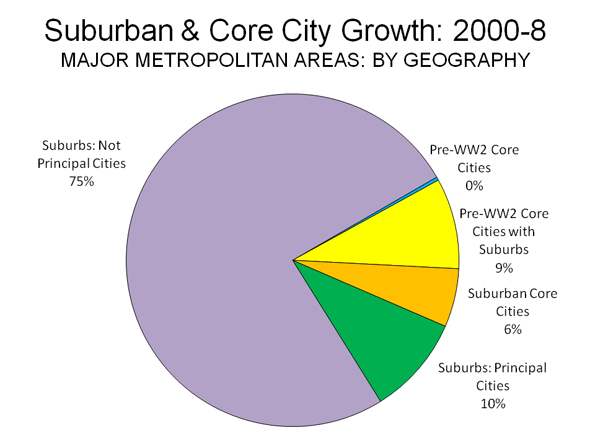

Generally, suburbs continue to grow much faster than the core cities (Table 1 and Figure 3). Between 2000 and 2008:

- Suburbs added 12.1 million residents, growing 11.1%.

- Core cities added 2.1 million residents, growing 4.8%. The greatest growth was in the Post War (Suburban) Core Cities, at 15.6%. The Pre-War Core Cities with Suburbs grew 6.8% and the Pre-War Cities grew 0.2% (Figure 4).

Virtually all of the core city growth was in the more suburban core cities, which is another indication that suburbanization is continuing. Further, the principal cities that are really suburban grew at a rate of 7.6%, more than double that of the core cities. This would seem to indicate that the migration data from the Census Bureau indicating a continued migration to the suburbs is, if anything, materially understated (by classification of some suburbs as principal cities).

At the same time, the demographic trends and prospects in the nation’s core cities are better than in the past. The rampant lawlessness that drove so many out of the cities in the 1970s has been replaced by law enforcement strategies developed under former New York mayor Rudi Giuliani. Core cities would become more attractive to future residents with serious reform of school performance and business regulation. Until that occurs, however, it seems unlikely that the movement from the cities to the suburbs will be reversed.

The city-centric media, with its faith-based demographics, continue to announce the demise of the suburbs. However, until migration data shows a net movement from the suburbs to the core cities, it will remain little more than disingenuous hype. At this point, it is not even close. From 2000 to 2008, suburban counties in major metropolitan areas gained 2,000,000 domestic migrants, while the core counties lost 4,600,000 domestic migrants (Note).

Note: Domestic migration data is reported at the county level and is thus not available for core cities, except where they are coterminous with counties (Such as New York, San Francisco, Baltimore and Washington).

| Table 2 | ||

| Metropolitan Areas and Core Cities | ||

| Metropolitan Area | Core City (ies) | Type of Core City |

| Atlanta-Sandy Springs-Marietta, GA | Atlanta | Pre-WW2 Core City with Suburbs |

| Austin-Round Rock, TX | Austin | Pre-WW2 Core City with Suburbs |

| Baltimore-Towson, MD | Baltimore | Pre-WW2 Core City |

| Birmingham-Hoover, AL | Birmingham | Pre-WW2 Core City with Suburbs |

| Boston-Cambridge-Quincy, MA-NH | Boston | Pre-WW2 Core City |

| Buffalo-Niagara Falls, NY | Buffalo | Pre-WW2 Core City |

| Charlotte-Gastonia-Concord, NC-SC | Charlotte | Pre-WW2 Core City with Suburbs |

| Chicago-Naperville-Joliet, IL-IN-WI | Chicago | Pre-WW2 Core City |

| Cincinnati-Middletown, OH-KY-IN | Cincinnati | Pre-WW2 Core City |

| Cleveland-Elyria-Mentor, OH | Cleveland | Pre-WW2 Core City |

| Columbus, OH | Columbus | Pre-WW2 Core City with Suburbs |

| Dallas-Fort Worth-Arlington, TX | Dallas | Pre-WW2 Core City with Suburbs |

| Denver-Aurora-Broomfield, CO | Denver | Pre-WW2 Core City with Suburbs |

| Detroit-Warren-Livonia, MI | Detroit | Pre-WW2 Core City |

| Hartford-West Hartford-East Hartford, CT | Hartford | Pre-WW2 Core City |

| Houston-Sugar Land-Baytown, TX | Houston | Pre-WW2 Core City with Suburbs |

| Indianapolis-Carmel, IN | Indianapolis | Pre-WW2 Core City with Suburbs |

| Jacksonville, FL | Jacksonville | Pre-WW2 Core City with Suburbs |

| Kansas City, MO-KS | Kansas City | Pre-WW2 Core City with Suburbs |

| Las Vegas-Paradise, NV | Las Vegas | Suburban Core City (Post -WW2) |

| Los Angeles-Long Beach-Santa Ana, CA | Los Angeles | Pre-WW2 Core City with Suburbs |

| Louisville/Jefferson County, KY-IN | Louisville | Pre-WW2 Core City with Suburbs |

| Memphis, TN-MS-AR | Memphis | Pre-WW2 Core City with Suburbs |

| Miami-Fort Lauderdale-Pompano Beach, FL | Miami | Pre-WW2 Core City |

| Milwaukee-Waukesha-West Allis, WI | Milwaukee | Pre-WW2 Core City with Suburbs |

| Minneapolis-St. Paul-Bloomington, MN-WI | Minneapolis | Pre-WW2 Core City |

| Minneapolis-St. Paul-Bloomington, MN-WI | St. Paul | Pre-WW2 Core City |

| Nashville-Davidson–Murfreesboro–Franklin, TN | Nashville | Pre-WW2 Core City with Suburbs |

| New Orleans-Metairie-Kenner, LA | New Orleans | Pre-WW2 Core City |

| New York-Northern New Jersey-Long Island, NY-NJ-PA | New York | Pre-WW2 Core City |

| Oklahoma City, OK | Oklahoma City | Pre-WW2 Core City with Suburbs |

| Orlando-Kissimmee, FL | Orlando | Suburban Core City (Post -WW2) |

| Philadelphia-Camden-Wilmington, PA-NJ-DE-MD | Philadelphia | Pre-WW2 Core City |

| Phoenix-Mesa-Scottsdale, AZ | Phoenix | Suburban Core City (Post -WW2) |

| Pittsburgh, PA | Pittsburgh | Pre-WW2 Core City |

| Portland-Vancouver-Beaverton, OR-WA | Portland | Pre-WW2 Core City with Suburbs |

| Providence-New Bedford-Fall River, RI-MA | Providence | Pre-WW2 Core City |

| Raleigh-Cary, NC | Raleigh | Suburban Core City (Post -WW2) |

| Richmond, VA | Richmond | Pre-WW2 Core City with Suburbs |

| Riverside-San Bernardino-Ontario, CA | Riverside | Suburban Core City (Post -WW2) |

| Rochester, NY | Rochester | Pre-WW2 Core City |

| Sacramento–Arden-Arcade–Roseville, CA | Sacramento | Pre-WW2 Core City with Suburbs |

| Salt Lake City, UT | Salt Lake City | Pre-WW2 Core City with Suburbs |

| San Antonio, TX | San Antonio | Pre-WW2 Core City with Suburbs |

| San Diego-Carlsbad-San Marcos, CA | San Diego | Pre-WW2 Core City with Suburbs |

| San Francisco-Oakland-Fremont, CA | San Francisco | Pre-WW2 Core City |

| San Francisco-Oakland-Fremont, CA | Oakland | Pre-WW2 Core City |

| San Jose-Sunnyvale-Santa Clara, CA | San Jose | Suburban Core City (Post -WW2) |

| Seattle-Tacoma-Bellevue, WA | Seattle | Pre-WW2 Core City with Suburbs |

| St. Louis, MO-IL | St. Louis | Pre-WW2 Core City |

| Tampa-St. Petersburg-Clearwater, FL | Tampa | Pre-WW2 Core City with Suburbs |

| Tucson, AZ | Tucson | Suburban Core City (Post -WW2) |

| Virginia Beach-Norfolk-Newport News, VA-NC | Norfolk | Pre-WW2 Core City with Suburbs |

| Washington-Arlington-Alexandria, DC-VA-MD-WV | Washington | Pre-WW2 Core City |

| See: Core City Classification Definitions |

Wendell Cox is a Visiting Professor, Conservatoire National des Arts et Metiers, Paris. He was born in Los Angeles and was appointed to three terms on the Los Angeles County Transportation Commission by Mayor Tom Bradley. He is the author of “War on the Dream: How Anti-Sprawl Policy Threatens the Quality of Life.”

Photograph: Suburban core city: Phoenix