Increasingly American politics are driven by generational change. The election of Donald Trump was not just a triumph of whiter, heartland America. It also confirmed the still considerable voting power of the older generation. Yet over time, as those of us who have lived long enough well know, generations decline, and die off, and new ones ascend.

Category: Demographics

-

The Screwed Generation Turns Socialist

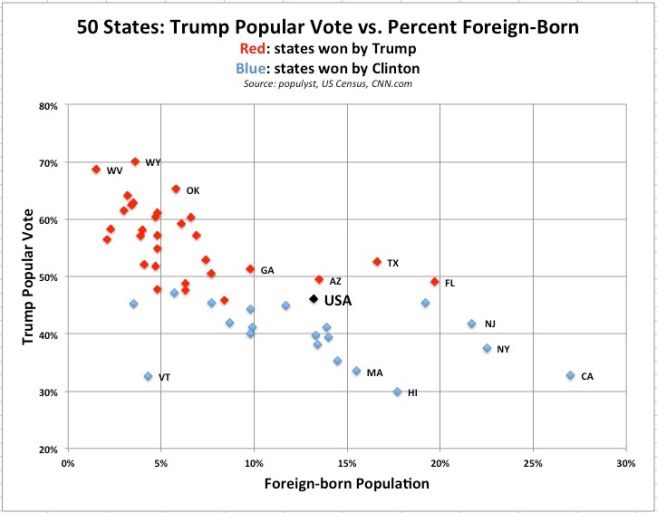

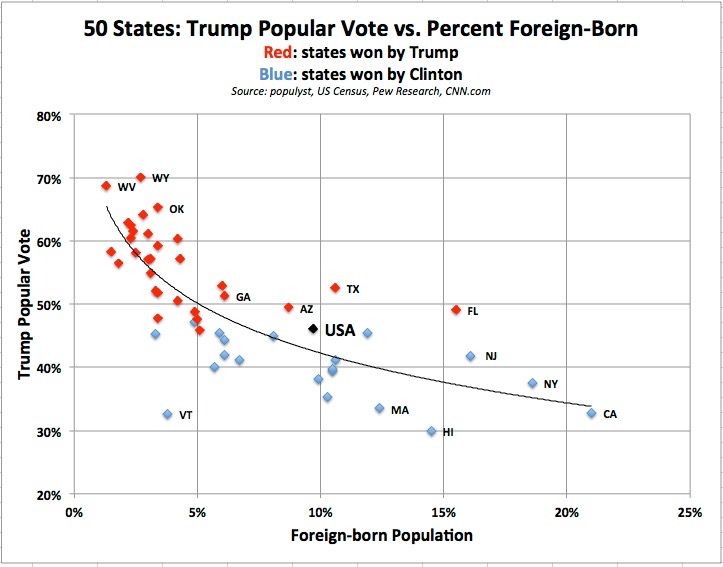

In this past election, those over 45 strongly favored Trump, while those younger than that cast their ballots for Clinton. Trump’s improbable victory, and the more significant GOP sweep across the country, demonstrated that the much-ballyhooed millennials simply are not yet sufficiently numerous or united enough to overcome the votes of the older generations.

Yet over time, the millennials—arguably the most progressive generation since the ’30s—could drive our politics not only leftward, but towards an increasingly socialist reality, overturning many of the very things that long have defined American life. This could presage a war of generations over everything from social mores to economics and could well define our politics for the next decade.

To best understand the battle lines, you must know the generations and their differences, and where they will leave this increasingly fractured republic.

The Greatest Generation

The last “civic generation” before the advent of the millennials—a term coined by generational theorists Neil Howe and William Strauss—was forged in the Depression, fought the Second World War, and managed the ensuing cold conflict with the old USSR. Born between 1901 and 1927, members of the much admired ++“greatest generation” were civic minded, embracing the idea that government provided an ideal mechanism to address the nation’s problems.

Like the millennials, who also follow this civic impulse, this generation was decisively Democratic. They are also, sadly, dying out, with the last remnants now in their 80s and 90s. According to generational analysts Morley Winograd and Michael Hais, this group was the only generation, besides the then small cadre of voting age millennials, to support John Kerry in 2004.

Under two million in 2010, per the Census, their numbers have dwindled to 750,000. Yet even so, as recently as 2014 , the remnants of the “greatest generation,” according to Pew, still favored the Democrats by 7 percentage points. Even fewer will be around in 2020 but those who remain may well remain liberal. It’s no sample, but my 93-year-old mother holds to pattern. Brought up poor in the Brownsville section of Brooklyn, she voted for the oldest and most left leaning major candidate—Bernie Sanders—in the primary and then cast her ballot for Hillary.

The Silent Generation Slow to fade

The “silent generation,” born between 1925 and 1942, mostly came of age in the conservative ’50s. These products of the Eisenhower era have been the prime beneficiaries of the sustained boom that took root between the end of the Second World War and the ’70s. As a result, they continue to hold a big share of America’s wealth—roughly 33 percent –even as they enter their seventies and eighties.

Given their embrace of the normative social values of their era, and their wealth, it’s not surprising that the silents have tended to the right. These older voters went for Trump by a significant margin, and overall, note Winograd and Hais, 53 percent lean to the Republicans, compared to just 40 percent who lean Democratic.

It would be a mistake to dismiss the silents before their time, as Democratic theorists sometimes seem to do. They still number upward of 29 million, and more than forty members of Congress hail from this generation, including, ironically, much of the Democratic leadership. Given their extended longevity, particularly among those in the upper middle class, they may remain influential well into the next decade.

Boomers: For Now, the Power Generation

The largest generation in American history before the millennials, the Baby Boomers were born between 1943 and 1960 and they remain the power generation. After all, both presidential candidates last year were clearly Boomers, with sufficient evidence of the narcissism that defines this generation. They also predominate in Congress, with 270 members, roughly half the total, in 2016. Hais estimates that they number between 75 and 82 million strong.

Ever since the turbulence of the ’60s, the Boomers have been sharply divided. Peace protests, psychedelics, and Woodstock defined only a part of that generation. Indeed, rather than tending to the left, the Boomers over time have slowly moved to the right. In 1992, note Winograd and Hais, they leaned 49 to 42 percent Democratic; last year, they leaned 49 to 45 Republican. Overall, Boomers supported Donald Trump by a narrow margin.

In the future, economics more than culture may define Boomer politics. Somewhat more socially liberal than the silent generation before them, they control a dominant share of the nation’s wealth—some 50 percent—and according to a recent Deloitte study will still control about 45 percent well into their seventies and eighties. This may make them naturally suspicious of the redistributionist agenda of the left Democrats, since this would naturally come from their wealth. They will also have to resist attempts by GOP reformers like Paul Ryan to meddle with Medicare, social security, and, for some, pensions. One reason Trump won over these voters—both in the primary and the general election—was by promising not to touch these holy of holies.

Xers: Long-time outsiders but soon the next power generation

Smaller than the boomers, and generally less privileged, the X generation—born between 1965 and 1981—gets short shrift among advertisers as well in the media, but seem poised to take power by the end of the decade. Numbering more than 65 million, they are a smaller generation than the boomers but they are slowly gaining control of politics, with 117 members in Congress compared to just five for millennials. They already dominate the leadership of the GOP. Paul Ryan is their poster boy.

Today, the Xers, many already in their fifties, have only 14 percent of the nation’s wealth, a relative pittance compared to the boomers. But by 2030, as the boomers finally start to fade from the picture, Xers should account for 31 percent of the nation’s wealth, twice the percentage for the millennials. Critically, the heads of most companies backed by venture capital come from this generation, according to the Harvard Business Review. Raised largely during the neo-conservative heyday of Reagan, George H.W. Bush, and Bill Clinton, Xers also dominate the ranks of managers at major companies.

Yet at the same time, they have faced a rockier economic ride than the boomers, suffering particularly in the 2007 housing crash. The percentage of Xers who own their own homes dropped far more precipitously compared to the more entrenched Boomers The impact was particularly tough on younger Xers, who often got into the market around the housing bust.

Millennials: The Red Generation?

The long-term hopes of the American left lie with the millennial generation. The roughly 90 million Americans born between 1984 and 2004 seem susceptible to the quasi socialist ideology of the post-Obama Democratic Party. They are also far more liberal on key social issues—gender and gay rights, immigration, marijuana legalization—than any previous generation. They comprise the most diverse adult generation in American history: some 40 percent of millennials come from minority groups, compared to some 30 percent for boomers and less than 20 percent for the silent and the greatest generations.

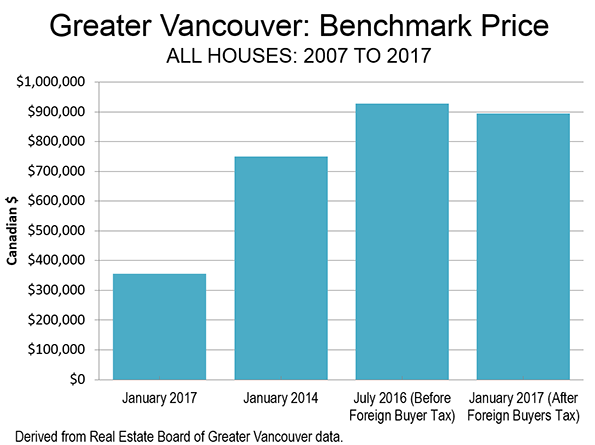

Millennials’ defining political trait is their embrace of activist government. Some 54 percent of millennials, notes Pew, favor a larger government, compared to only 39 percent of older generations. One reason: Millennials face the worst economic circumstances of any generation since the Depression, including daunting challenges to home ownership. More than other generations, they have less reason to be enamored with capitalism.

These economic realities, along with the progressive social views, has affected their voting behavior. Millennials have voted decisively Democratic since they started going to the polls, with 60 percent leaning that direction in 2012 and 55 percent last year. They helped push President Obama over the top, and Hillary Clinton got the bulk of their votes last year. But their clear favorite last year was self-described socialist Bernie Sanders, who drew more far millennial votes in the primaries than Clinton and Trump combined.

The West is red, too? Maybe, maybe not.

Roughly half of Millennials have positive feelings about socialism, twice the rate of the previous generation. Indeed, despite talk about a dictatorial Trump and his deplorables, the Democratic-leaning Millennials are more likely to embrace limits on free speech and are far less committed to constitutional democracy than their elders. Some 40 percent, notes Pew, favor limiting speech deemed offensive to minorities, well above the 27 percent among the Xers, 24 among the boomers, and only 12 percent among silents. They are also far more likely to be dismissive about basic constitutional civil rights, and are even more accepting of a military coup than previous generations.

Millennials clearly have not been well-schooled by the founders’ vision. This could augur a grim prospect, a kind of voluntary 1984 with cellphones and social media. Potential economic conflicts between millennials and boomers and Xers for scarce resources could accelerate support for a federally mandated agenda of redistribution. After all, if they have little money, own even less and have modest prospects for achieving what their parents did, why not socialism, constitutional norms be damned?

Yet this future is not guaranteed. Already white Millennials, still 60 percent of the total youth electorate (less than the 73 Anglo share among older voters but still a large bloc), show signs of moving to the right, particularly outside the coasts. Overall, they backed Trump by 48 to 43 percent and, notes one recent Tufts University survey, they were more enthusiastic about their candidate than were the Clinton backers.

Other factors could slow the lurch to the left. There is a growing interest in third party politics, not so much Green but libertarian; 8 percent of Millennials voted for Third Party candidates, twice the overall rate. Overall, Tufts finds that moderates slightly outpace liberals, although conservatives remain well behind. Millennials, note Winograd and Hais, also dislike “top down” solutions and may favor radical action primarily at the local level and more akin to Scandinavia than Stalinism.

As Millennials grow up, start families, look to buy houses, and, worst of all, start paying taxes, they may shift to the center, much as the Boomers did before them. Redistribution, notes a recent Reason survey, becomes less attractive as incomes grow to $60,000 annually and beyond. This process could push them somewhat right-ward, particularly as they move from the leftist hothouses of the urban core to the more contestable suburbs.

Yet even given these factors, Republicans have their work cut out for them as the generational wheel turns. Certainly, to be remotely competitive, they must abandon socially conservative ideas that offend most Millennials. The GOP’s best chance lies with making capitalism work for this group, sustaining upward mobility and expanding property ownership. If we see the creation of a vast generation of property serfs with little opportunity for advancement, America’s future is almost certain to be redder, a lot less market-oriented, and perhaps a lot more authoritarian than previous generations have ever contemplated.

This piece first appeared in The Daily Beast.

Joel Kotkin is executive editor of NewGeography.com. He is the Roger Hobbs Distinguished Fellow in Urban Studies at Chapman University and executive director of the Houston-based Center for Opportunity Urbanism. His newest book The Human City: Urbanism for the rest of us, was published in April by Agate. He is also author of The New Class Conflict, The City: A Global History, and The Next Hundred Million: America in 2050. He lives in Orange County, CA.

The Screwed Generation Turns Socialist

Increasingly American politics are driven by generational change. The election of Donald Trump was not just a triumph of whiter, heartland America. It also confirmed the still considerable voting power of the older generation. Yet over time, as those of us who have lived long enough well know, generations decline, and die off, and new ones ascend.

In this past election, those over 45 strongly favored Trump, while those younger than that cast their ballots for Clinton. Trump’s improbable victory, and the more significant GOP sweep across the country, demonstrated that the much-ballyhooed millennials simply are not yet sufficiently numerous or united enough to overcome the votes of the older generations.

Yet over time, the millennials—arguably the most progressive generation since the ’30s—could drive our politics not only leftward, but towards an increasingly socialist reality, overturning many of the very things that long have defined American life. This could presage a war of generations over everything from social mores to economics and could well define our politics for the next decade.

To best understand the battle lines, you must know the generations and their differences, and where they will leave this increasingly fractured republic.

The Greatest Generation

The last “civic generation” before the advent of the millennials—a term coined by generational theorists Neil Howe and William Strauss—was forged in the Depression, fought the Second World War, and managed the ensuing cold conflict with the old USSR. Born between 1901 and 1927, members of the much admired ++“greatest generation” were civic minded, embracing the idea that government provided an ideal mechanism to address the nation’s problems.

Like the millennials, who also follow this civic impulse, this generation was decisively Democratic. They are also, sadly, dying out, with the last remnants now in their 80s and 90s. According to generational analysts Morley Winograd and Michael Hais, this group was the only generation, besides the then small cadre of voting age millennials, to support John Kerry in 2004.

Under two million in 2010, per the Census, their numbers have dwindled to 750,000. Yet even so, as recently as 2014 , the remnants of the “greatest generation,” according to Pew, still favored the Democrats by 7 percentage points. Even fewer will be around in 2020 but those who remain may well remain liberal. It’s no sample, but my 93-year-old mother holds to pattern. Brought up poor in the Brownsville section of Brooklyn, she voted for the oldest and most left leaning major candidate—Bernie Sanders—in the primary and then cast her ballot for Hillary.

The Silent Generation Slow to fade

The “silent generation,” born between 1925 and 1942, mostly came of age in the conservative ’50s. These products of the Eisenhower era have been the prime beneficiaries of the sustained boom that took root between the end of the Second World War and the ’70s. As a result, they continue to hold a big share of America’s wealth—roughly 33 percent –even as they enter their seventies and eighties.

Given their embrace of the normative social values of their era, and their wealth, it’s not surprising that the silents have tended to the right. These older voters went for Trump by a significant margin, and overall, note Winograd and Hais, 53 percent lean to the Republicans, compared to just 40 percent who lean Democratic.

It would be a mistake to dismiss the silents before their time, as Democratic theorists sometimes seem to do. They still number upward of 29 million, and more than forty members of Congress hail from this generation, including, ironically, much of the Democratic leadership. Given their extended longevity, particularly among those in the upper middle class, they may remain influential well into the next decade.

Boomers: For Now, the Power Generation

The largest generation in American history before the millennials, the Baby Boomers were born between 1943 and 1960 and they remain the power generation. After all, both presidential candidates last year were clearly Boomers, with sufficient evidence of the narcissism that defines this generation. They also predominate in Congress, with 270 members, roughly half the total, in 2016. Hais estimates that they number between 75 and 82 million strong.

Ever since the turbulence of the ’60s, the Boomers have been sharply divided. Peace protests, psychedelics, and Woodstock defined only a part of that generation. Indeed, rather than tending to the left, the Boomers over time have slowly moved to the right. In 1992, note Winograd and Hais, they leaned 49 to 42 percent Democratic; last year, they leaned 49 to 45 Republican. Overall, Boomers supported Donald Trump by a narrow margin.

In the future, economics more than culture may define Boomer politics. Somewhat more socially liberal than the silent generation before them, they control a dominant share of the nation’s wealth—some 50 percent—and according to a recent Deloitte study will still control about 45 percent well into their seventies and eighties. This may make them naturally suspicious of the redistributionist agenda of the left Democrats, since this would naturally come from their wealth. They will also have to resist attempts by GOP reformers like Paul Ryan to meddle with Medicare, social security, and, for some, pensions. One reason Trump won over these voters—both in the primary and the general election—was by promising not to touch these holy of holies.

Xers: Long-time outsiders but soon the next power generation

Smaller than the boomers, and generally less privileged, the X generation—born between 1965 and 1981—gets short shrift among advertisers as well in the media, but seem poised to take power by the end of the decade. Numbering more than 65 million, they are a smaller generation than the boomers but they are slowly gaining control of politics, with 117 members in Congress compared to just five for millennials. They already dominate the leadership of the GOP. Paul Ryan is their poster boy.

Today, the Xers, many already in their fifties, have only 14 percent of the nation’s wealth, a relative pittance compared to the boomers. But by 2030, as the boomers finally start to fade from the picture, Xers should account for 31 percent of the nation’s wealth, twice the percentage for the millennials. Critically, the heads of most companies backed by venture capital come from this generation, according to the Harvard Business Review. Raised largely during the neo-conservative heyday of Reagan, George H.W. Bush, and Bill Clinton, Xers also dominate the ranks of managers at major companies.

Yet at the same time, they have faced a rockier economic ride than the boomers, suffering particularly in the 2007 housing crash. The percentage of Xers who own their own homes dropped far more precipitously compared to the more entrenched Boomers The impact was particularly tough on younger Xers, who often got into the market around the housing bust.

Millennials: The Red Generation?

The long-term hopes of the American left lie with the millennial generation. The roughly 90 million Americans born between 1984 and 2004 seem susceptible to the quasi socialist ideology of the post-Obama Democratic Party. They are also far more liberal on key social issues—gender and gay rights, immigration, marijuana legalization—than any previous generation. They comprise the most diverse adult generation in American history: some 40 percent of millennials come from minority groups, compared to some 30 percent for boomers and less than 20 percent for the silent and the greatest generations.

Millennials’ defining political trait is their embrace of activist government. Some 54 percent of millennials, notes Pew, favor a larger government, compared to only 39 percent of older generations. One reason: Millennials face the worst economic circumstances of any generation since the Depression, including daunting challenges to home ownership. More than other generations, they have less reason to be enamored with capitalism.

These economic realities, along with the progressive social views, has affected their voting behavior. Millennials have voted decisively Democratic since they started going to the polls, with 60 percent leaning that direction in 2012 and 55 percent last year. They helped push President Obama over the top, and Hillary Clinton got the bulk of their votes last year. But their clear favorite last year was self-described socialist Bernie Sanders, who drew more far millennial votes in the primaries than Clinton and Trump combined.

The West is red, too? Maybe, maybe not.

Roughly half of Millennials have positive feelings about socialism, twice the rate of the previous generation. Indeed, despite talk about a dictatorial Trump and his deplorables, the Democratic-leaning Millennials are more likely to embrace limits on free speech and are far less committed to constitutional democracy than their elders. Some 40 percent, notes Pew, favor limiting speech deemed offensive to minorities, well above the 27 percent among the Xers, 24 among the boomers, and only 12 percent among silents. They are also far more likely to be dismissive about basic constitutional civil rights, and are even more accepting of a military coup than previous generations.

Millennials clearly have not been well-schooled by the founders’ vision. This could augur a grim prospect, a kind of voluntary 1984 with cellphones and social media. Potential economic conflicts between millennials and boomers and Xers for scarce resources could accelerate support for a federally mandated agenda of redistribution. After all, if they have little money, own even less and have modest prospects for achieving what their parents did, why not socialism, constitutional norms be damned?

Yet this future is not guaranteed. Already white Millennials, still 60 percent of the total youth electorate (less than the 73 Anglo share among older voters but still a large bloc), show signs of moving to the right, particularly outside the coasts. Overall, they backed Trump by 48 to 43 percent and, notes one recent Tufts University survey, they were more enthusiastic about their candidate than were the Clinton backers.

Other factors could slow the lurch to the left. There is a growing interest in third party politics, not so much Green but libertarian; 8 percent of Millennials voted for Third Party candidates, twice the overall rate. Overall, Tufts finds that moderates slightly outpace liberals, although conservatives remain well behind. Millennials, note Winograd and Hais, also dislike “top down” solutions and may favor radical action primarily at the local level and more akin to Scandinavia than Stalinism.

As Millennials grow up, start families, look to buy houses, and, worst of all, start paying taxes, they may shift to the center, much as the Boomers did before them. Redistribution, notes a recent Reason survey, becomes less attractive as incomes grow to $60,000 annually and beyond. This process could push them somewhat right-ward, particularly as they move from the leftist hothouses of the urban core to the more contestable suburbs.

Yet even given these factors, Republicans have their work cut out for them as the generational wheel turns. Certainly, to be remotely competitive, they must abandon socially conservative ideas that offend most Millennials. The GOP’s best chance lies with making capitalism work for this group, sustaining upward mobility and expanding property ownership. If we see the creation of a vast generation of property serfs with little opportunity for advancement, America’s future is almost certain to be redder, a lot less market-oriented, and perhaps a lot more authoritarian than previous generations have ever contemplated.

This piece first appeared in The Daily Beast.

Joel Kotkin is executive editor of NewGeography.com. He is the Roger Hobbs Distinguished Fellow in Urban Studies at Chapman University and executive director of the Houston-based Center for Opportunity Urbanism. His newest book The Human City: Urbanism for the rest of us, was published in April by Agate. He is also author of The New Class Conflict, The City: A Global History, and The Next Hundred Million: America in 2050. He lives in Orange County, CA.