For most of those which were great once are small today; And those that used to be small were great in my own time. Knowing, therefore, that human prosperity never abides long in the same place, I shall pay attention to both alike

–Herodotus, Fifth Century B.C.

If the great Greek chronicler and “father of history” Herodotus were alive today, he would have whiplash. In less than a lifetime, we have seen the rapid rise of a host of dynamic new global cities – and the relative decline of many others. With a majority of the world’s population now living in cities, what these places do with their new wealth ultimately will shape this first truly urban century.

Just 25 years ago, when you walked down the Bund in Shanghai, there were few cars and no modern towers. The rough sidewalks expanded into the streets to accommodate a mass of poorly dressed pedestrians. A decade later, Moscow was in the midst of a particularly grungy interlude, filled with stolid people waiting in lines for shoddy consumer goods. You could hail a cab, and pay for it, with a pack of Kents.

Today, these two cities have emerged from their socialist shackles with scores of high-rise projects either already up or on the drawing board. This, of course, has come with a price; Moscow hotel accommodations – cheap if dingy a quarter century ago – last year ranked as the world’s most expensive. Shanghai, meanwhile, has bustling traffic, a new subway and a 100-story office tower; it is about to begin construction on another that tops out at 121 stories.

Also remarkable: the rise of other great cities – Mumbai, Bangalore and Hyderabad in India; Beijing; Sao Paulo, Brazil; and Dubai – that a quarter century ago were either obscure or better known for their destitution than their rapid construction.

Of course, none of these cities’ wealth or economic power have passed leading global centers like Tokyo, London, Paris, New York, Chicago, Los Angeles, Seoul, Singapore and Hong Kong. But our list of emerging global cities is clearly gaining on them – and with remarkable speed.

The main reason lies in economic fundamentals. Over the past 25 years, per capita income, based on purchasing power parity, grew by over 400% in India and a remarkable 1,500% in China. The bulk of that wealth came from urban centers like Mumbai and Shanghai, while the largest concentrations of poverty remained in the countryside. In that same period, U.S. per capita income grew by 245%; growth in most Western European nations was less than that.

The nascent recovery in the world economy will certainly amplify these trends. China, as opposed to the U.S., is leading the economic resurgence, drawing in commodities from its rising business partners in all continents.

For the most part, basic industries lead the way. Manufacturing has propelled the rise of the great Chinese cities. In Brazil, Sao Paulo’s growth spans everything from shoes and aerospace to technology. The city also dominates Brazil’s growing energy sector, both renewable and traditional. Energy – overwhelmingly of the fossil fuel variety – has powered the rise of Moscow and Dubai. It’s not always pretty. As the old Yorkshire saying has it, where there’s muck, there’s brass.

Of course, the past year’s drop in oil prices has set back things a bit. California real estate investor Bob Christiano notes that more than half of the construction projects in the United Arab Emirates – worth $582 billion total – were put on hold in 2008. But now that the price of oil seems back on the rise, you can expect things to perk up in places like Dubai, Moscow and Sao Paulo.

Not all our emerging cities are in the developing or former Communist world. North America boasts at least three genuine emerging world cities: Calgary, in Canada, and Houston and Dallas. These regional economies have been built around energy and expanding industrial power. They also have enjoyed rapid population growth. Last year, Houston and Dallas grew more than any other metropolitan region in the country; over the past decade, their populations have increased six times more rapidly than New York, Los Angeles, Chicago or San Francisco.

But it’s not all a demographic game; cities like Phoenix and Las Vegas have similarly enjoyed rapid growth but do not fit on the rising global cities list. The key difference lies in the Texan cities’ rising corporate power. Houston, with 27 Fortune 500 firms, has passed Chicago in the number of Fortune 500 companies, while Dallas, with 14, ranks third. Together, the two Texan cities account for about as many Fortune firms as New York, once home to almost a third of the nation’s largest companies.

Similarly, Calgary has become Toronto’s main challenger for corporate headquarters in Canada, a move sparked not only by oil wealth but lower taxes and regulation. The region now easily boasts the highest per capita income in the country. Its long-term main rival in growth may prove to be provincial cousin Edmonton, which sits closer to Alberta’s massive oil sands deposits.

In Australia, Perth, located on the Indian Ocean and close to critical commodities such as iron ore, has also emerged in a big way. Australia’s richest city has become a major urban threat to long-established Sydney and Melbourne, with growth driven both by domestic as well as foreign migration and development.

These emerging world cities also have survived the housing crisis much better than their national competitors. The growth of India and China has created an ever-richer market for commodities, as well as expertise residing in places like Perth, Calgary, Dallas and Houston, much of it built around commodity and resource extraction. The evolving ties between burgeoning world cities also spill over into the growing tourism industry in Perth and the expanding medical service complex in Houston.

Another group flocking to the developing world’s super-stars: architects and civil engineers, many of them from more established first-world cities like New York, London, Los Angeles and San Francisco. Over the past 25 years, most of the biggest rail, road, airport and sanitation systems have been built not in Europe or America, but in East and South Asia, the Middle East and Brazil. Even as the West tries to work through its housing crisis, residential real estate prices are on the rise in cities like Mumbai, Bangalore, Beijing and Shanghai.

The lure is irresistible, particularly for the young and ambitious. Just last month, Adam Mayer, a 20-something formerly employed architect from San Francisco, relocated to Beijing. He sees the chaos around him, but has plunged into the opportunity. “As I wait for our economy to recover,” he told me, “I am enjoying the ride as I witness perhaps one of the most compelling urban development stories of the 21st century.”

High-rise office buildings have emerged as the biggest signs of the new order among global cities. Shanghai is already the fourth-tallest city in the world, with 21 buildings over 700 feet. Of the world’s 10 tallest buildings, only one – the former Sears (now Willis) Tower in Chicago – resides in the U.S. or Europe. There are now more tall buildings in Asia than in North America, and of the tallest 10 completed in 2006, four were in China and four in the Middle East. When completed, the Burj Dubai will stand as the world’s tallest.

Although less awesome, the shift in skylines can also be seen in Russia. Until recently, Moscow had no buildings higher than the 787 feet of Moscow State University. Now, the Kremlin city has 14 towers complete or on the way, including one that will replace the current Naberezhnaya Tower; it will be Europe’s tallest building. Another project, a billion-dollar Chinatown, is being proposed with investors from China.

Even with their rapid growth and increasingly modern gloss, these cities don’t tend to make the usual lifestyle-based “best cities” lists. Munich, Zürich, Copenhagen and Vancouver may be somnolent compared to Beijing or Bangalore, but they tend to be far wealthier, better organized, cleaner and safer – and they have far less poor people. Even our current global metropolises like Tokyo, London and New York have been able to hone the cultural amenities that make for a gracious urbanity.

In contrast, by their very nature, boomtowns often give shorter shrift to the environment, the aesthetics of place and the more important aspects of community. Shaghai’s “tofu like” soil may not be ideal for massive high-rise buildings, just as some of Dubai’s buildings, some believe, may be helping to erode the Persian Gulf coastline.

These upstarts are often too busy building and trying to impress the rest of the world to focus on architecture or plan niceties to make the heroic routine of everyday life more pleasant, notes London-based architect Eric Kuhne, who has worked on major projects in Moscow, Dubai and other Persian Gulf cities. Such places tend to be “abrupt and rude” in their development, but also “honest in every way” – they are the new kids on the block, with more money and power than seasoning.

Like parvenus throughout history, Kuhne adds, these burgeoning power centers harbor “a desire to be seen as relevant, as ‘modern’, as shockingly new. In the stampede for a shining presence on the horizon, they both have been mesmerized…perhaps hypnotized…by their own profligacy of uncontrolled development.”

Yet, Kuhne reminds us, you could have said the same thing about now-reigning world capitals like New York, London, Tokyo, Chicago or Los Angeles. These cities also “experienced a similar riot-panic in the post-war boom years of the ’50s. We destroyed the intricacy of centuries of urbanism [and] sacrificed community and family fabric for home ownership and autonomy.”

Ultimately, the salvation for these cities may lie, Kuhne suggests, not in mimicry of Western ways but in drawing inspiration from their own ancient traditions. After all, Chinese, Arabs and Russians are not newcomers to city-building. But however they decide to build their new cities, these countries will be providing the blueprint for all of our urban futures.

This article originally appeared at Forbes.

Joel Kotkin is executive editor of NewGeography.com and is a presidential fellow in urban futures at Chapman University. He is author of The City: A Global History. His next book, The Next Hundred Million: America in 2050, will be published by Penguin early next year.

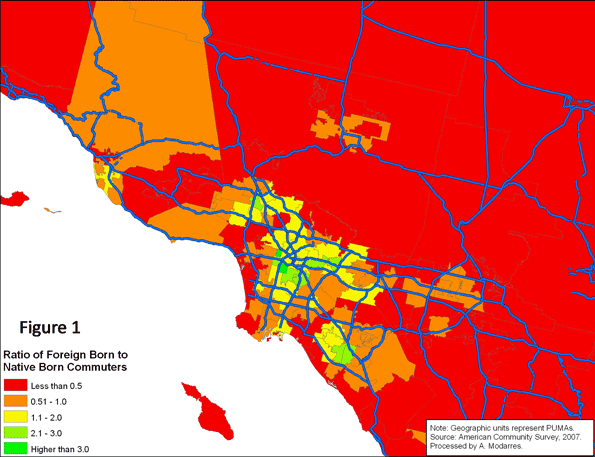

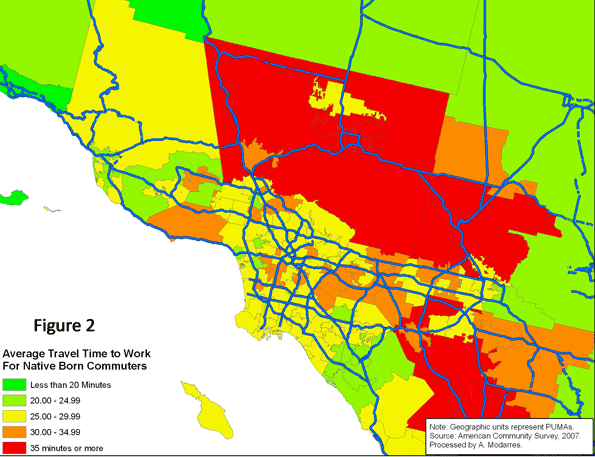

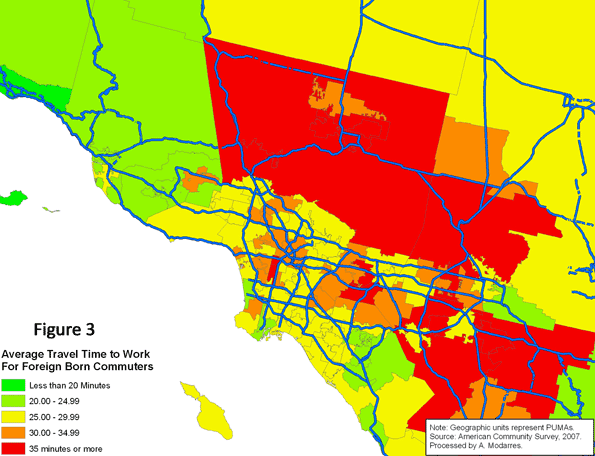

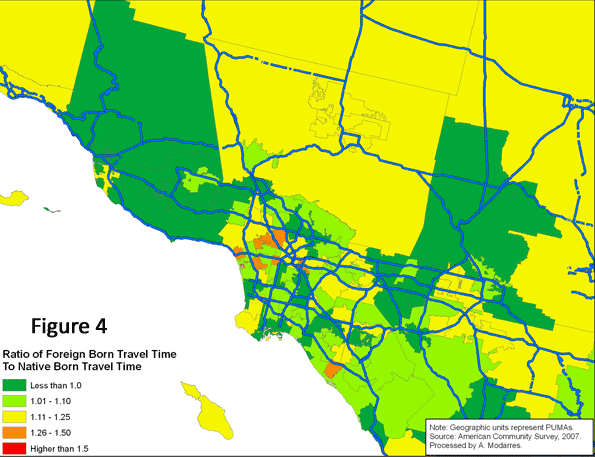

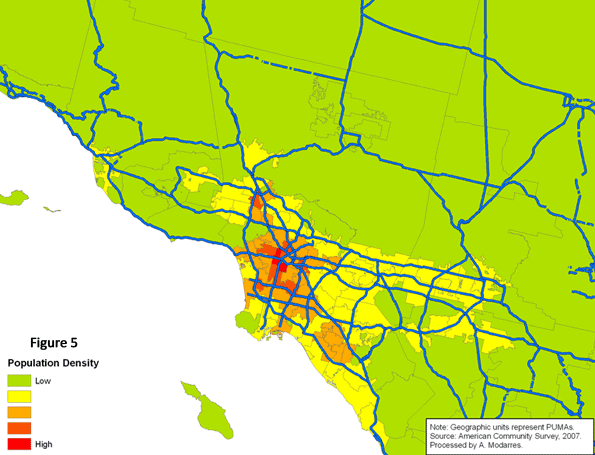

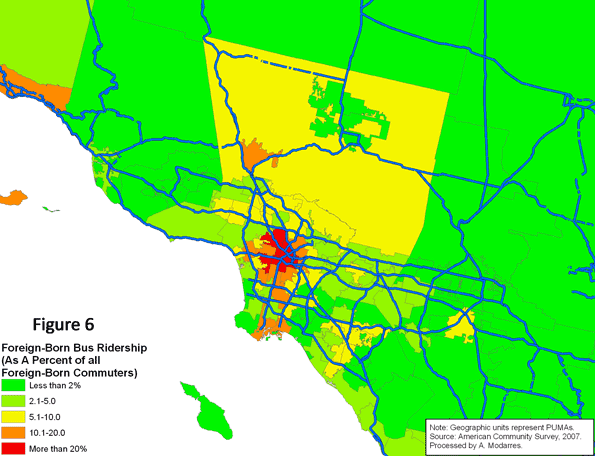

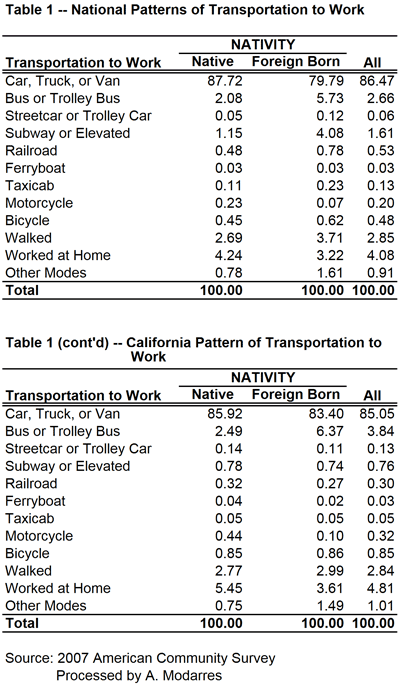

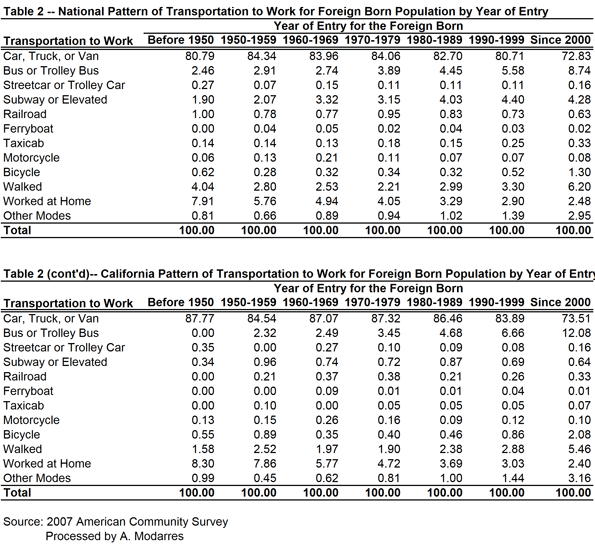

Based on the 2007 American Community Survey, 117.3 million native-born and 21.9 million foreign-born individuals commuted to work. As Table (1) illustrates, a higher percentage of immigrants rode buses (5.7% vs. 2.1%) and subways (4.1% vs. 1.2%) and many walked to work (3.7% vs. 2.7%). A much smaller percentage drove to work (79.8% vs. 87.7%). Unfortunately, despite their higher usage of alternate means of transportation to work, or perhaps because of it, the commute to work time was on average longer for the foreign-born commuters than their native-born counterparts (28.8 minutes versus 24.7).

Based on the 2007 American Community Survey, 117.3 million native-born and 21.9 million foreign-born individuals commuted to work. As Table (1) illustrates, a higher percentage of immigrants rode buses (5.7% vs. 2.1%) and subways (4.1% vs. 1.2%) and many walked to work (3.7% vs. 2.7%). A much smaller percentage drove to work (79.8% vs. 87.7%). Unfortunately, despite their higher usage of alternate means of transportation to work, or perhaps because of it, the commute to work time was on average longer for the foreign-born commuters than their native-born counterparts (28.8 minutes versus 24.7).

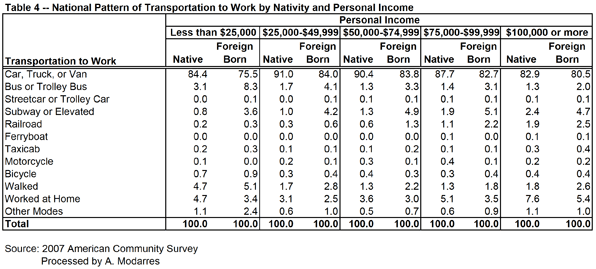

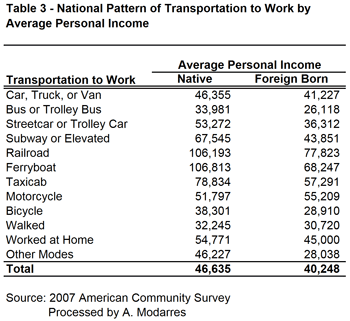

Even so, their rates are still slightly better than the native-born (compare Tables 1 and 2). This may be in part because of their lower incomes (see Table 3) yet at every level of income they are still more likely to take transit. Table (4) illustrates this point by grouping commuters into income categories and their nativity. In every income category, immigrants use their cars less and are more likely to use public transportation, even though their car ridership increases with income.

Even so, their rates are still slightly better than the native-born (compare Tables 1 and 2). This may be in part because of their lower incomes (see Table 3) yet at every level of income they are still more likely to take transit. Table (4) illustrates this point by grouping commuters into income categories and their nativity. In every income category, immigrants use their cars less and are more likely to use public transportation, even though their car ridership increases with income.