Few places have received more accolades in recent years than Austin, the city that ranked first on our list of the best big cities for jobs. Understanding what makes this attractive, fast-growing city tick can tell us much about what urban growth will look like in the coming decades.

Austin’s success is not surprising since, in many ways, it starts on third base. Two of its greatest assets result from the luck of the draw; it’s both a state capital and home to a major research university.

Our ranking of the best cities for job growth includes many college towns–from Fargo, N.D., (home to North Dakota State) to Athens, Ga., (University of Georgia), Durham-Chapel Hill, N.C., (Duke and University of North Carolina) and College Station, Texas (Texas A&M).

Being a state capital also helps. Baton Rouge, La., home to both the state government and Louisiana State University, ranked seventh on our list of the best medium-sized cities for employment. This confluence of institutions also accounts in large part for the relatively decent rankings of two Midwestern cities, Indianapolis and Columbus, Ohio, in spite of the generally sad situation in that region.

That’s because colleges and state governments offer stable employment–since they cannot or will not outsource jobs to India or China. These places also tend to be inhabited by reasonably well-educated people whose stable incomes makes them less vulnerable to contractions in competitive industries like finance, manufacturing, construction or information.

“We’re pretty close to recession-proof,” suggest Chris Bradford, a local attorney and blogger in Austin. “It’s almost anti-cyclical. In bad times, the students want to stay here.”

There is a third factor, however, that adds to Austin’s special sauce: the fact that it is located in Texas, the one fast-growing mega-state. With low taxes and low regulation at the state level, Austin–no doubt to many locals’ consternation–is a great environment not only for public sector employment but also private sector growth.

Its success contrasts dramatically with the relatively poor employment status of capitals in business-unfriendly states (such as Sacramento, Calif., which ranked 60th among large cities) as well as other college towns like Ann Arbor, Mich., home to one of the nation’s best public universities, the University of Michigan. (Among medium-sized cities, Ann Arbor came in 93rd.)

Austin, essentially, reaps the benefits of being a deep blue, Democratic island in a red-state sea. The university and state government employ large numbers of people who might want higher taxes and greater regulation–but they can talk the redistributionist’s game without feeling any of the pain.

This is not to say that Austin itself–that is, its urban core area–does not try to trot out its blue, and “green,” trimmings. Like every college town, Austin likes smart growth, mass transit and high density.

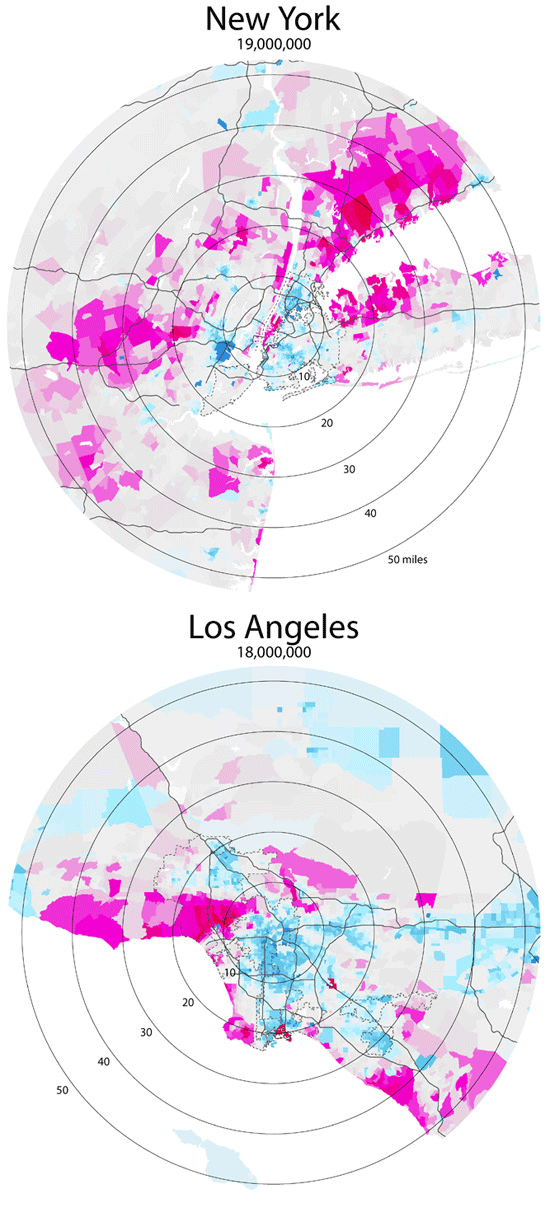

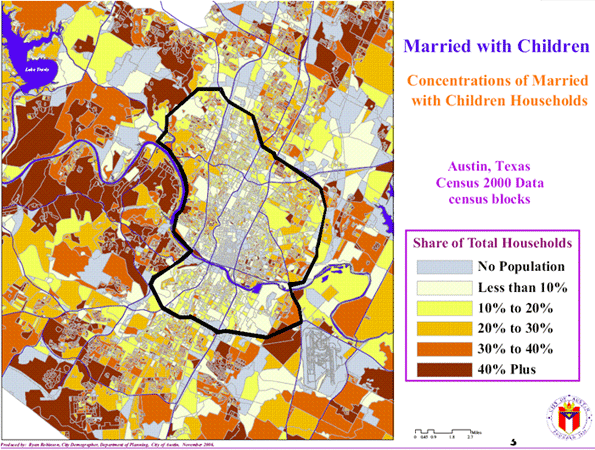

But in reality, Austin is not a dense region. In fact, its metropolitan population per acre puts it in the middle of the nation’s largest areas, well behind not only Los Angeles and New York but also Houston and Dallas.

Even central Austin seems rather spread out and suburban compared to traditional East Coast cities. Smaller, older homes–mainly cottages–dominate neighborhoods close to downtown. Recent attempts to go high-rise have not been notably successful, as the auction signs on the sides of some new towers suggest.

Yet the urban center increasingly represents less and less of the area’s total employment and houses fewer and fewer of its residences. Today, the city itself is home to well under half the metropolitan population of 1.5 million.

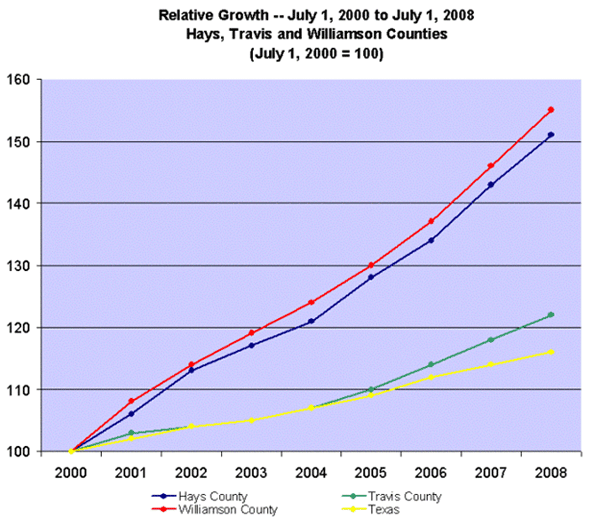

As in many regions, notes blogger Bradford, over the past decade the strongest growth has occurred in Austin’s periphery. Even as the city itself has enjoyed strong job and population growth, the biggest increases have taken place in suburban outposts outside city limits, like Williamson, Bastrop and Hays counties, as well as parts of Travis, the county that is home to Austin. In fact, Williamson was the nation’s sixth fastest-growing county last year, while Hays ranked 10th.

Surprisingly, these suburban areas are the places most driving Austin’s economic success. Why? Two reasons: affordability and livability. By Texas standards, the city is not cheap. It costs between $350,000 and $400,000 for a nice three- or four-bedroom house in a good school district, say, 20 minutes from downtown. However, a similar place in the ‘burbs of Silicon Valley, San Francisco, Boston or Irvine would run at least twice as much.

Local Realtor and blogger Shannan Gonyea-Reimer adds that, a bit further away from town, home prices can drop as low as $150,000. “People come from California, and they are shocked,” she says.

This price structure, along with the human capital attracted to the University of Texas, has in turn propelled the rapid expansion of the non-governmental economy in places like Cedar Creek and Round Rock, home to Dell. A recent Brookings study estimates that central Austin employment grew by almost 13% between 1998 and 2006. The number of jobs more than 10 miles from the central business district increased by 77,523, or 62%, according to the study.

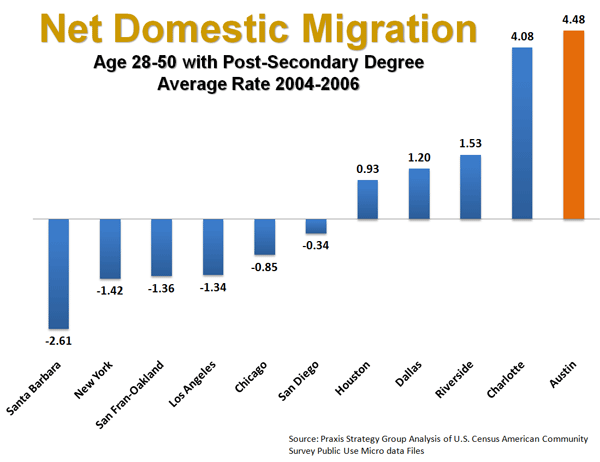

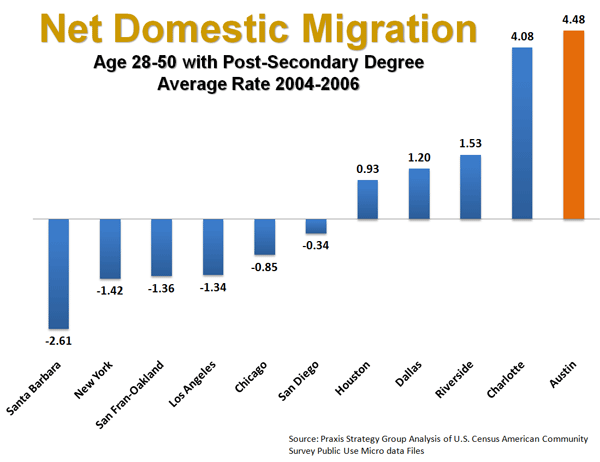

Austin has seen remarkable overall employment growth–almost 34%–in the last decade. With that figure, it leaves its major hip tech rivals in the dust. Over the same period, for example, San Jose/Silicon Valley has lost 6% of its jobs; San Francisco, around 1.6%. Boston, Austin’s other big high-tech competitor, enjoyed only a 1.2% gain.

Again, this growth stems in part from the unique combination of both an appealing city center and attractive suburbs. The city’s lively urban core remains a lure for affluent professionals, young singles and, of course, students. However, unlike places like New York, Boston and San Francisco, the sprawling ‘burbs provide an affordable place for people to move to when their hardcore clubbing days are over.

“California might work well for the apartment-dwelling, single-guy lifestyle person, but when you get married, you can’t afford Los Gatos,” says former Silicon Valley entrepreneur Mike Shultz, the CEO of Infoglide, a software firm headquartered on Austin’s outer ring. “In Austin, the same person can grow up, move into a reasonable house and have a reasonable life.”

This does much to explain why Austin has enjoyed a migration pattern unlike that of its primary competitors. Its residents may start off hip and cool, but the city also accommodates their often inevitable evolution to Ozzie and Harriet. This allows individuals and companies to plan to stick around. One doesn’t have to have the short-term mentality so common in the Bay Area, L.A., Boston or New York.

Ultimately, it is this combination of a “cool” downtown culture–with excellent restaurants as well as great music–and a more sedate, affordable periphery that makes Austin a home run.

“It has a hip cool side to it,” Shultz observes, “but it’s also a great place to raise kids.”

A caveat to all this: We also have to consider scale. With roughly 1.5 million people, Austin simply offers more convenient choices than a megalopolitan behemoth like Los Angeles, New York or the Bay Area. In Austin, nice, single-family homes within walking distance of cool urban streets are not uncommon or absurdly expensive–and even a larger, more affordable house out in the suburbs is usually less than a half an hour from downtown.

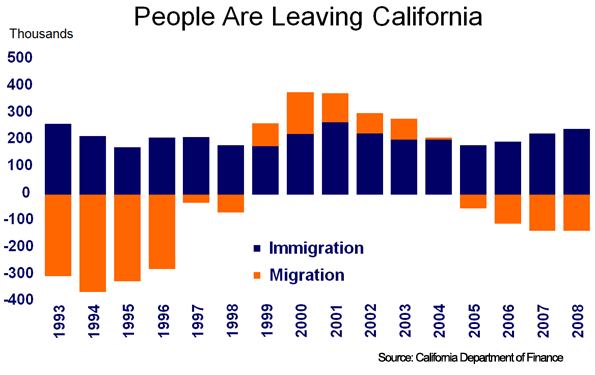

Additionally, Texas, unlike its main rival California, is not teetering on the edge of bankruptcy and is instead a stable long-term bet in this recession. Rather than haggling with bankers or public employee unions, it is busy building its future: attracting new comers, investing in its university and building new transportation infrastructure.

“Austin is off the charts livable, but it’s in a state that makes it viable,” says Shultz, the entrepreneur. “You can’t say that about California and many of the other places where our competitors are.”

This article originally appeared at Forbes.

Joel Kotkin is executive editor of NewGeography.com and is a presidential fellow in urban futures at Chapman University. He is author of The City: A Global History and is finishing a book on the American future.

and is finishing a book on the American future.