There have been four great growth waves in American history. In each case, there was an attractive new frontier, which not only drew migrating waves of people seeking new opportunity, but also developed large new bases of industry, wealth, and power. These waves have also created top-tier world cities in their wake. The first three of these waves were:

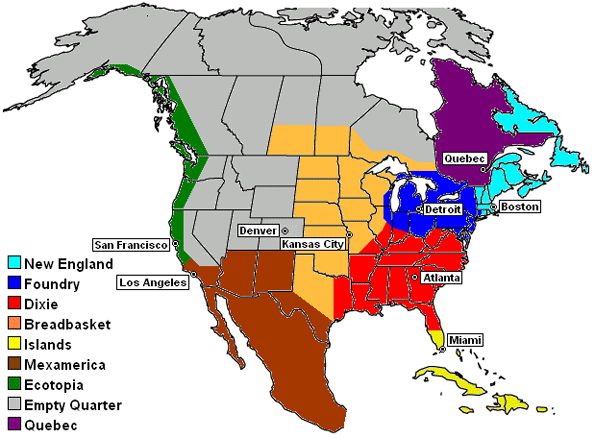

- The Boston, New York, Philadelphia, Baltimore, Washington DC corridor was America’s original land of opportunity, industry, wealth, and power. New York was the big winner, and DC and Boston still do quite well.

- The rise of the agricultural and industrial Midwest, including Chicago, Detroit, Pittsburgh, Cleveland, and St. Louis. The fall here has been a hard one as manufacturing moved abroad, but Chicago still stands as a world-class city produced during the region’s heyday.

- The great westward migration, mostly focused on California, but with ancillary growth in adjacent and west coast states. This migration started well before World War 2, but really took off after the war, and produced two top-tier mega-metros – Los Angeles and the San Francisco Bay Area – and several successful second-tiers like Seattle, San Diego, Las Vegas, and Phoenix.

These waves are not clearly distinct, but overlap each other. As one region matures and starts to level off, the next region starts its growth wave. And that’s the situation now as California shows clear signs of having peaked: gigantic tech and housing crashes plus economic and domestic outmigration as tax, cost-of-living, housing, and regulatory burdens rise and a dysfunctional government teeters towards financial collapse.

The fourth wave is increasingly clear and follows the same California model of a single focus mega-state and an ancillary region: Texas and the new South.

Just as California had its pre-war growth surge, Texas had its first real growth waves with the 20th-century post-Spindletop oil boom. California had the dust bowl migration of the 30s, and Texas the oil boom migration of the 70s. But the real super-surge has become clearer in the new century as California hands off the baton to Texas. This growth wave really covers much of the South, but Texas is the 800lb gorilla vs. states like Georgia and North Carolina, just as California dominates over Washington, Nevada, and Arizona. Texas even looms over Florida, which certainly has experienced incredible population growth to become the fourth-largest state, but has had considerably less success with building industry, wealth, and power. Florida’s wealth – like that of Arizona – comes in part from people who built wealth elsewhere but moved or bought a second home there. Neither place is home to many Fortune 500 headquarters, an area where Texas has excelled.

California had its agriculture and oil barons before WW2, but the real story there was the post-war rise of the entertainment, defense, aerospace, biotech, trade and technology industries. In a similar way, Texas’ oil tycoons are just the tip of the coming surge of wealth and power in industries such as technology, health care, biotech, defense, trade, transportation, aerospace, finance, telecom, and alternative energy in addition to traditional oil and gas (in fact, Texas is the #1 wind power state).

The great cities emerging from this new wave are Atlanta, Dallas-Ft.Worth, and Houston. They dominate the census growth stats (Houston story), and all indications are that Houston will pass Philadelphia in the 2010 census to join Dallas-Ft.Worth in the top 5 metros along with New York, Los Angeles, and Chicago. DFW and Houston are even approaching the combined San Francisco Bay Area population of 6.1 million, and Texas passed California and New York for the #1 ranking in the Fortune 500 HQ rankings last year.

Want more evidence? Check out this impressive video on the DFW-Austin-San Antonio-Houston Texas Triangle with an overwhelming list of statistics that make the case. In the video, they refer to the region as the 18m-strong “Texaplex” – a play on the “Metroplex” nickname for Dallas-Ft. Worth. You can also see their Texaplex informational brochure here (pdf).

When you look at it in this historical context, it’s clear Texas and the new South will be the focal point of America’s growth for at least the next few decades. History also says at least one, and possibly more, truly top-tier world cities will emerge from this wave – and it could be argued that some have already. It’s easy to get caught up in the day-to-day hubub and crisis-of-the-moment, but take a minute to stand back and see the big picture. Those living in or moving to Texas and the new South are part of a great historical wave that’s just starting to really take off, the same as being in Chicago at the turn of the 19th-century or in California after WW2. Pretty cool, eh?

Tory Gattis is a Social Systems Architect, consultant and entrepreneur with a genuine love of his hometown Houston and its people. He covers a wide range of Houston topics at Houston Strategies – including transportation, transit, quality-of-life, city identity, and development and land-use regulations – and have published numerous Houston Chronicle op-eds on these topics.