This essay is part of a new report from the Center for Opportunity Urbanism titled “The Texas Way of Urbanism“. Download the entire report here.

Any observer of urbanism in America knows that Austin tops numerous rankings of urban dynamism. Austin — defined as a metropolitan area, not just the city — is consistently atop Forbes’ annual list of Best Cities for Jobs in America over the past five years, which is why so many people move there in the first place.

In other surveys Austin has been ranked the number one city for young entrepreneurs, small businesses, jobs, millennial homebuyers, singles, dog owners, and food trucks. Its central downtown ZIP code has more bars per capita than any other ZIP code in the country by a long shot. Last year, Savills ranked Austin over San Francisco as the nation’s best technology city, and college information aggregator Niche ranked the University of Texas, situated on the north end of downtown, as the top public university in America. And, of course, Austin has long claimed the title of “live music capital of the world.”

No surprise then that a visitor to a gathering of technology entrepreneurs in any mid-size to large American city will hear someone talking about how we need to be more like Austin. And Austin is indeed a success story, but one that on examination does not look exactly how outsiders may expect.

Our conclusion here is that although Austin’s urban vibe is critical, its success has more to do with some distinctly Texan features, including development on the periphery, low taxes, affordable housing (particularly in comparison with coastal California) and less stringent regulation. It is the culture of opportunity, as much as anything else, that defines the Texas capital, and makes it so distinct from its other “hip and cool” rivals.

The New Dynamism

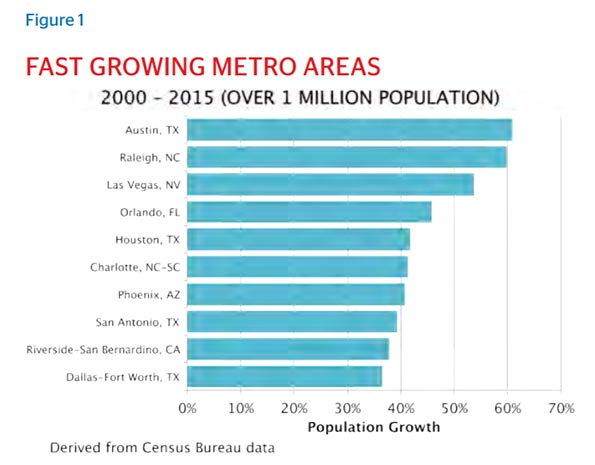

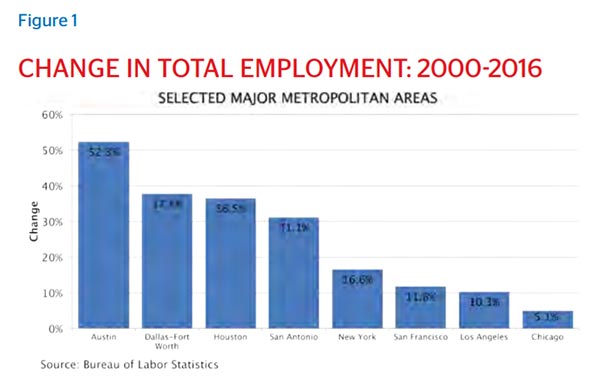

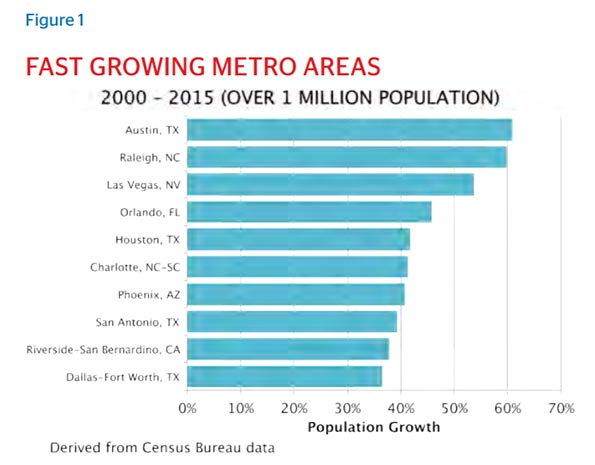

When George W. Bush was watching the 2000 presidential election results from the governor’s residence in Austin, Texas, he was sitting in a city of 1.2 million people. Since then, Austin has grown 60 percent to over 2 million residents. Only Raleigh, NC, has come close to matching that rate of growth over 15 years. Austin and Raleigh are 20 percentage points ahead of fifth place Houston. Perhaps most remarkable, however, is Austin’s growth since 2010, the worst financial meltdown since the Great Depression. The city grew by 16.6 percent, while Raleigh grew 12.7 percent. Austin has largely defied gravity since the economic collapse.

Among the nation’s 53 metro areas with populations over 1 million, the fifteen that have experienced double-digit growth since 2000 are all located in the south and west, including Texas’s four largest metros. And of the top 25 fastest-growing cities since 2010, the only city not in the south, west, or northwest is Columbus, Ohio, in 24th position. Columbus is the only city east of the Mississippi River and north of the Mason-Dixon line growing at a rate above six percent.

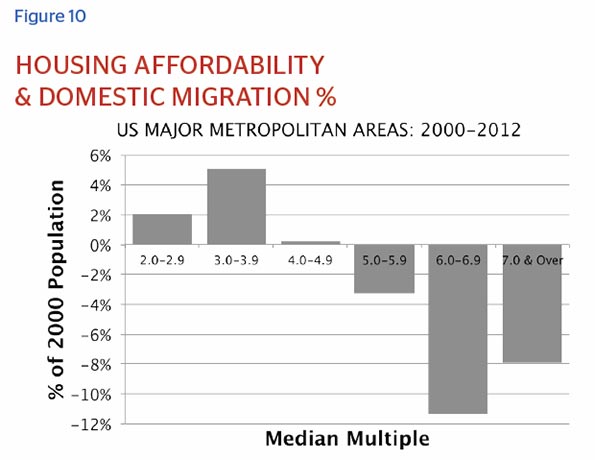

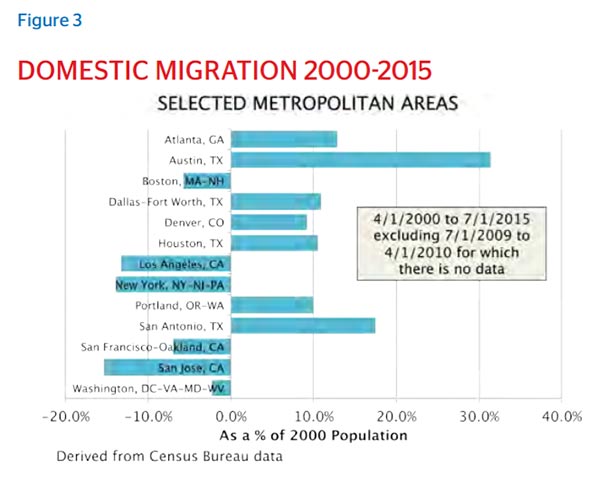

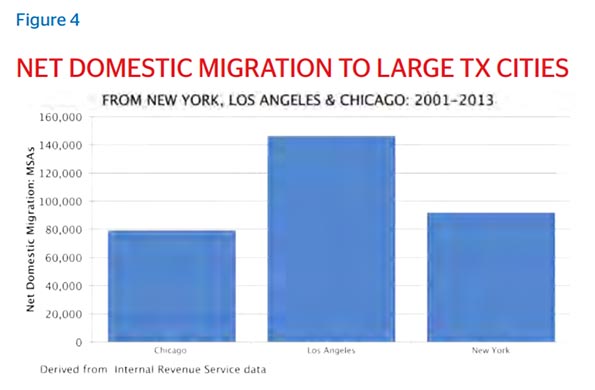

Weather is a factor but America’s fast-growing cities attract aspiring workers and business owners through a blend of favorable economic conditions, new infrastructure, and increasingly, proximity to talent. Political sclerosis and economic elitism in coastal and northern cities have served as a helping hand, pushing workers away from a toxic blend of rising expenses and falling quality of life. Using a mix of Census data, cross-metro moving requests on moving.com, and cross-metro searches on realtor.com, a recent Realtors study found New York, Chicago, San Jose, and Los Angeles are among the top five cities losing the most domestic migrants to mostly smaller, newer Sun Belt cities. In the same study the top ten gainers are Sun Belt cities, with the exception of Portland, Oregon, all who offer newer, more affordable housing stock than in the prime metro areas of New York, Illinois, and California.

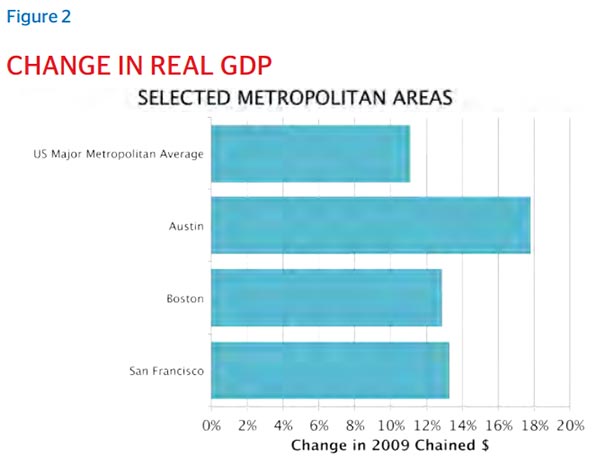

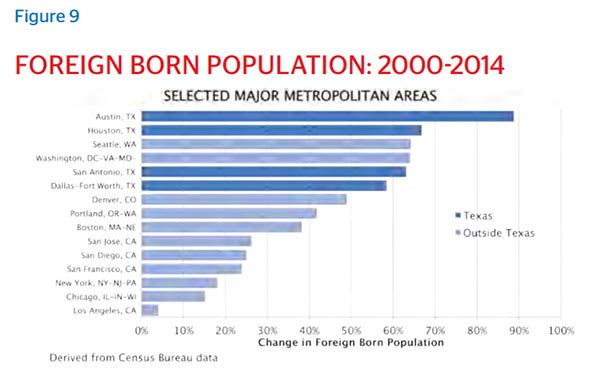

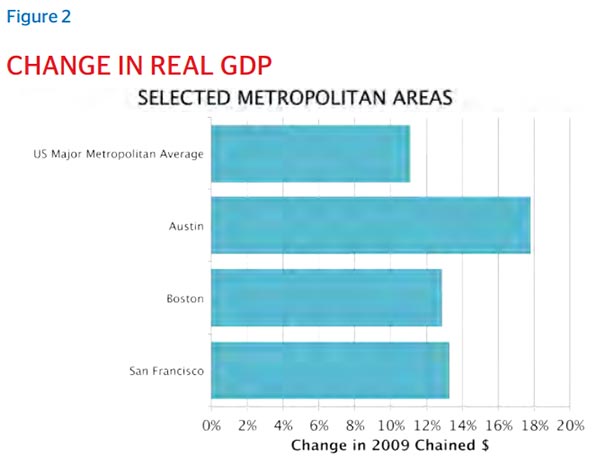

Arguably no city in the country has taken advantage of these conditions more than Austin. Since 2009, the low point of the Great Recession, its metro area GDP has grown 31 percent. By comparison, San Francisco and Boston each grew by 13 percent during the same period. The national average for U.S. metro areas was 11 percent.

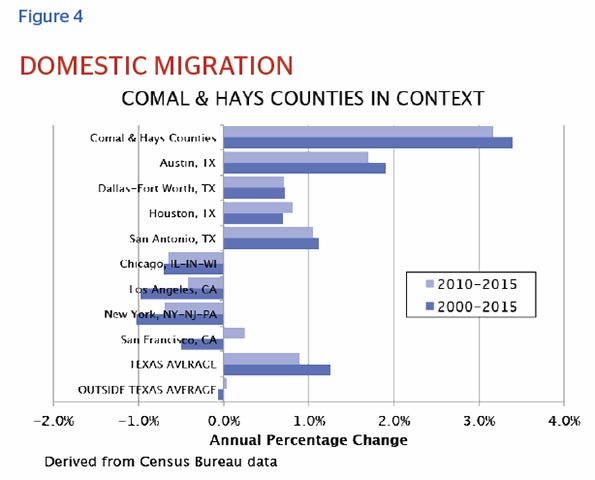

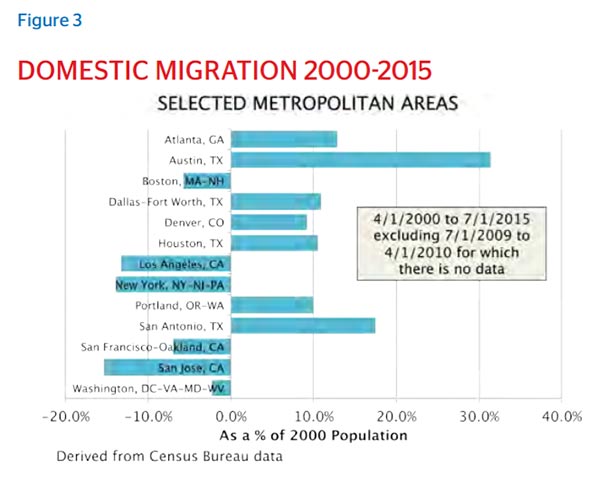

Demographically, domestic migration drives Austin’s economy. Austin has had to innovate and import a lot of talent. Austin has become a quintessential knowledge economy that thrives not so much by cultivating natural and historical resources, but by absorbing ideas, innovation and talent from elsewhere and selling them as products back to the world.

Anyone who has spent any time in Austin understands the tension that exists in the city between the defenders of its erstwhile charm as an unconventional music and college town and boosters of its high-growth technology cosmopolitanism. Whatever the community’s gatekeepers contend, however, Austinites themselves think that the massive influx of people is inextricably bound to its economic growth.

An annual survey of Austin residents casts this phenomenon in clear relief. When asked what they think Austin has gained by its population growth over the past five years, residents cite a stronger economy as their top pick. Compared to the 22 percent of Austinites who cite “more diversity” and 7 percent who say “more creativity,” 42 percent say Austin’s explosive population growth has been a boon to the city’s economy. Even those who have lived in Austin for more than 20 years believe the economy has benefited from great migration to the city.

An openness to newness, strangers, and change are hallmarks of Austin’s economic culture. Perhaps rooted in the city’s past as a music-centric, indie-friendly college town, these hallmarks have translated well economically for the city.

The Great Migration Game

Austin’s migration story can perhaps be understood best in contrast with Silicon Valley. No metro area in America can compare to the Bay Area in terms of the sheer size and force of its technology community, Austin’s attractiveness has grown, in large part , unlike in San Francisco and San Jose, tech workers in Austin are able to afford housing close to the office, raise kids close to good school options, and enjoy a variety of cultural amenities in close proximity.

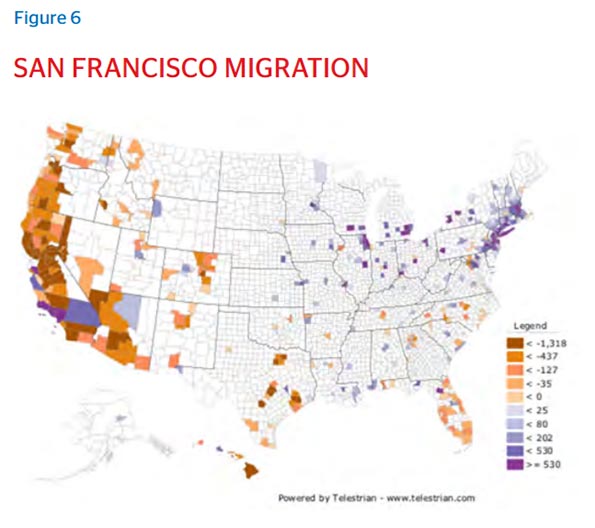

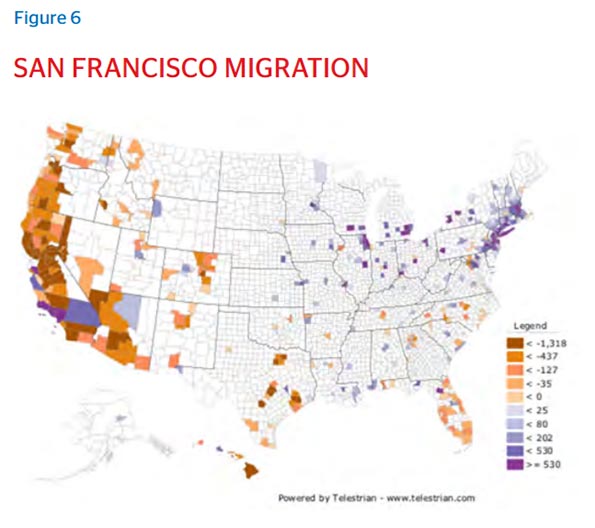

Between 1991 and 2013, people moved between Austin and 304 MSAs. Of these, Austin only experienced a net loss to eleven. Compare that to San Francisco. The gem of the Bay Area lost population to 133 of the 242 MSAs with which it “traded” population. For San Jose, the figures are 127 out of 253. In other words, while the Bay Area lost population to well over half of the MSAs it has traded with across the country, Austin’s loss was just 3.6 percent.

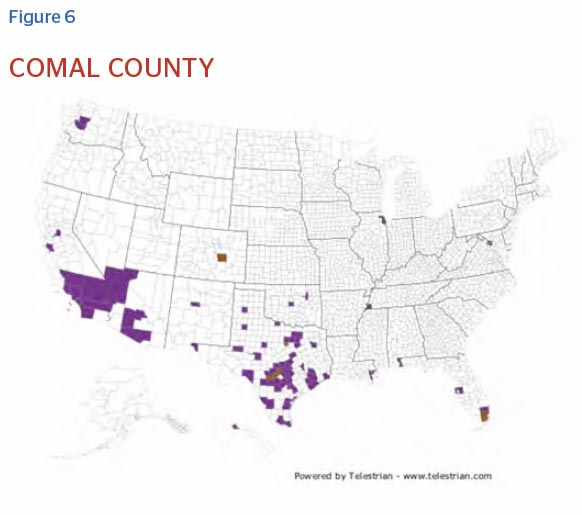

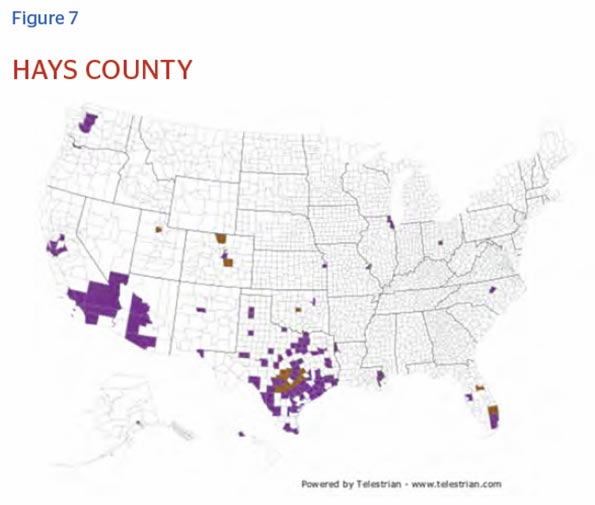

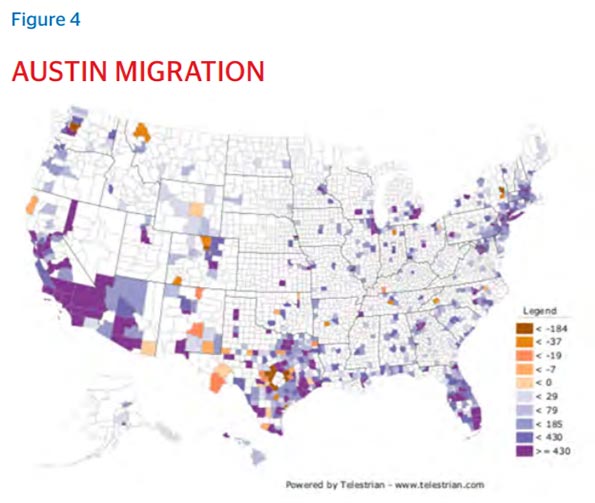

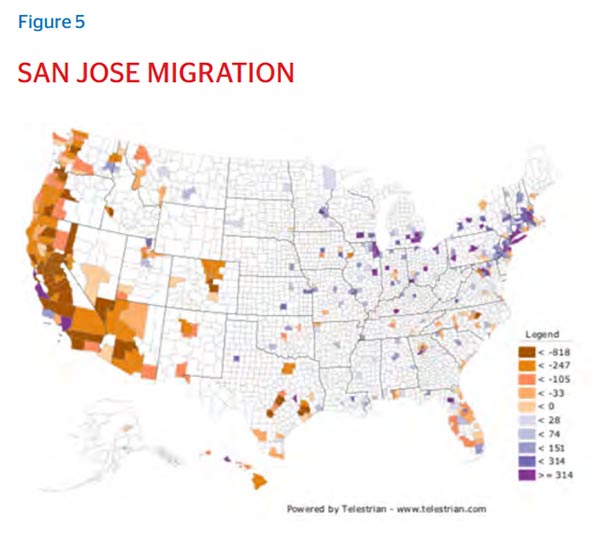

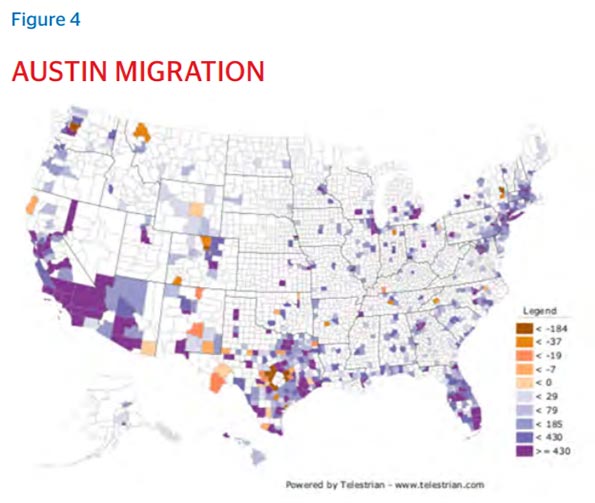

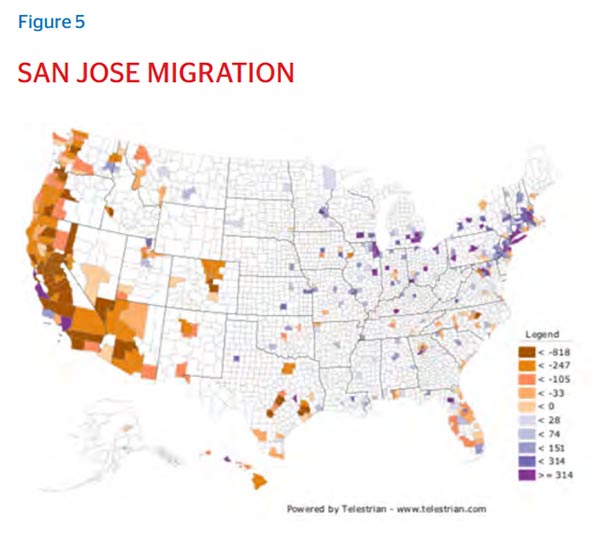

Figures 5 and 6 show clearly how the Bay Area has dispatched population to a number of western and southern boomtowns, whereas Austin has pulled in workers and families from every population centers all across the country.

Silicon Valley is renowned for its high-level talent pool. It attracts the best and the brightest from around the world to work in the most vibrant technology ecosystem in the world. However, when one looks at where U.S. cities export most of their talent, the numbers tell a slightly different story.

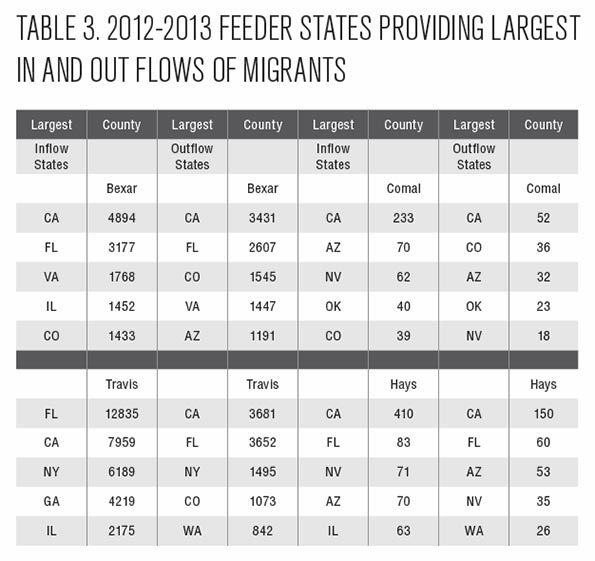

First, Austin is more of a regional talent destination than Silicon Valley. Since 1991, Austin has seen a net population increase of more than 33,000 people from Houston and 21,000 from Dallas. San Jose has lost thousands of people to both Texas cities over the same period of time. So has San Francisco. Perhaps that is expected, given Austin’s proximity to its fellow Texan metropolitan areas.

But the pull is much greater from California than one would suspect. During the same period, Austin attracted nearly 20,000 migrants from the Los Angeles metropolitan area, which sent only 15,000 to San Jose. Austin also saw thousands of arrivals from San Diego during the same period.

The other tech-heavy, talent-centric cities in the Northwest also prefer Austin. Net migration from Seattle to Austin has been positive since 1991, while San Francisco and San Jose have lost a combined 25,500 people to Seattle in the same time period. Portland tells an even more dramatic story. A city frequently compared to Austin, Oregon’s commercial capital has lost more people to its Texas peer than it has gained, while Silicon Valley has lost tens of thousands of residents to their northern neighbor. In contrast, since 1991, San Jose and San Francisco have exported nearly 51,000 people to Portland and Austin combined.

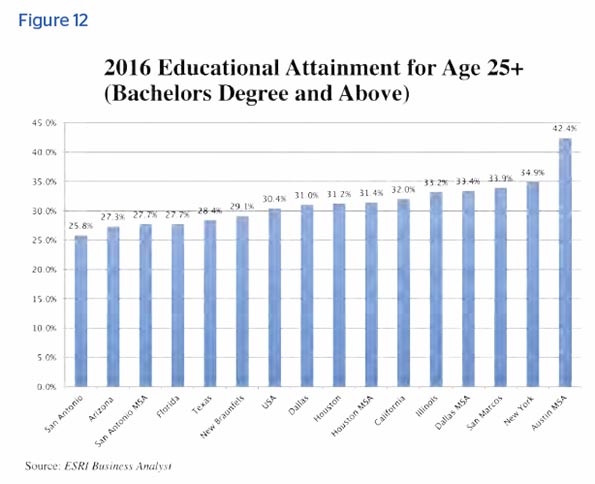

Second, looking at talent centers nationwide, Austin outperforms the Bay Area quite decisively as cities with a high proportion of college-educated residents have consistently chosen the Texas capital as an ultimate destination over Silicon Valley. Raleigh, for example, the only other American city to come close to matching Austin’s rate of growth over the past five years, has lost more people to Austin than it has gained since 1991, but both San Francisco and San Jose have lost population to Raleigh over the same period. In other words, plenty of people are choosing to leave the Bay Area for North Carolina, but the talent base in North Carolina has a fonder eye for Austin.

Other talent centers display a bias for Austin as well. The three largest cities on Wallet Hub’s 2015 list of the educated cities in America — New York, Los Angeles, and Chicago — have all sent more people to Austin than to the Bay Area, despite an enormous tech-led boom in the area. Washington, D.C. has become a talent boomtown in its own right, owing to the stability of employment for the knowledge workers the federal industrial complex increasingly needs and rewards. Yet it has exported more workers to Austin than to San Jose and San Francisco combined over the past twenty years. Provo and Colorado Springs, the mountain West’s talent hubs, have also lost people to Austin but gained people from San Jose and San

Francisco.

Opportunity Cities Win

For cities aspiring to grow as Austin has grown, the first order of business is to understand Austin as an opportunity city, not just a technology center or music capital. So what are the hallmarks of an opportunity city?

First, Austin, like other Texas cities, is friendly to those who want to start and grow a business. These are cities in which small businesses not only participate in, but also drive economic growth. A recent study conducted by the American City Business Journals ranked cities with 500,000 or more residents according to 16 indicators constructed to measure the vitality of the small business sectors in American cities. Austin ranked number one on the list because of the relationship between small business job growth and overall economic growth. San Francisco and San Jose ranked sixth and ninth, respectively, bested by nimbler hot spots such as Miami and Provo. Austin has also made other high-level appearances over the past few years on similar rankings, such as CNBC’s “Friendliest Cities for Small Business” list.

Small businesses are woven into the fabric of Austin’s economic ecosystem. Austin’s small businesses are ahead of the national average and a significant source of the tireless job creation engine for which Austin has earned a national reputation. Companies in Austin with fewer than 100 workers account for 35 percent of the area’s workforce, and yet they created enough jobs in 2009-2011 to offset the job losses caused by Austin’s largest employers after the Great Recession.

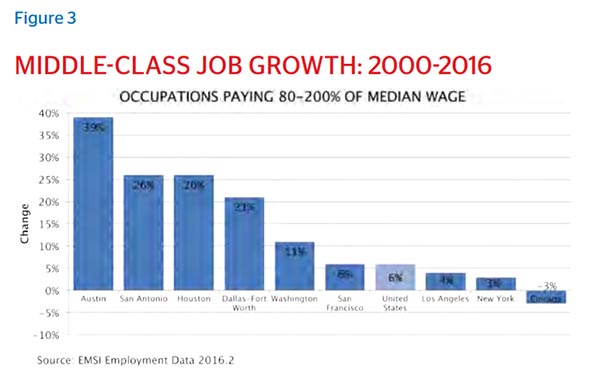

Second, an opportunity city is a jobs city. Small businesses by themselves do not necessarily guarantee that a city will have a healthy jobs environment, but a critical mass of new small companies typically does, especially if a significant minority grow into larger companies.

Austin reflects the growing body of academic literature on the impact of new firms on the labor market. Startups and other young companies generate the vast majority of net new jobs in America and spur income growth, especially for younger workers. New companies in Austin are the fuel that powers the creation of new jobs at a rate impressively above the national average.

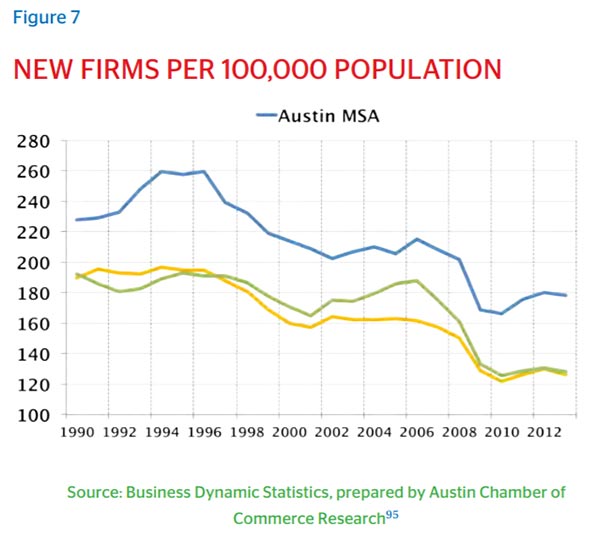

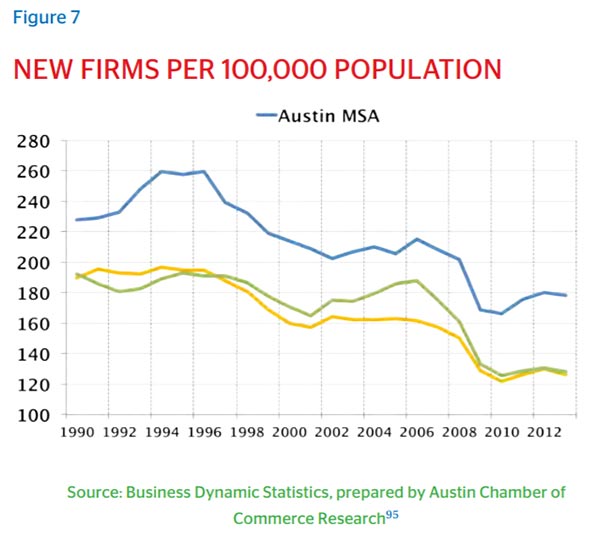

New firm formation in Austin tracks with general national trends, but it does so at a consistently higher rate. As figure 7 shows, Austin has produced a significantly greater share of new firms per capita compared to the rest of country over the past 20 years, and it rebounded faster post-recession than the nation as a whole. The tech centers of Raleigh, San Francisco, and San Jose have all had lower startup rates than Austin since 2010.

Austin is the only major metro in Texas creating as many or more new firms than it was pre-recession. Just three years after the nation’s economic nadir, Austin created more new firms in absolute terms than it ever had. It also produces a disproportionately high number of startups for its size. In the Kauffman Foundation’s Index of Startup Activity, Austin has been in the top two spots for a few years running.

In addition to its startup culture, Austin is a premier relocation destination, especially for companies looking to expand operations in a business-friendly atmosphere with an abundance of talent. Since 2004, nearly one-third of all high-tech company relocations and expansions to Austin from elsewhere have come from California. Among these are household name giants such as Apple, Google, eBay, Oracle, PayPal, and Facebook.

A churning startup culture drives a dynamic job-creation ecosystem. Austinites work more hours per week than the national average, enjoy the lowest unemployment rate among the nation’s top 50 metro areas and experienced non-farm payroll growth at the 3rd fastest rate last year.

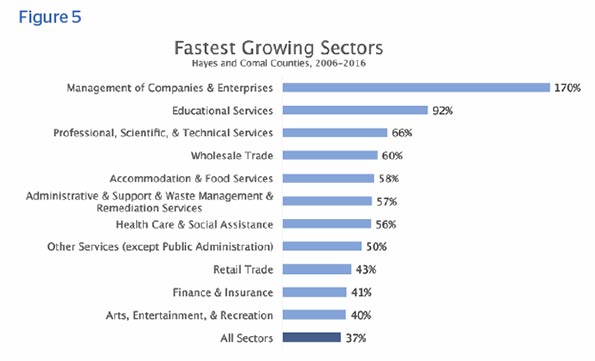

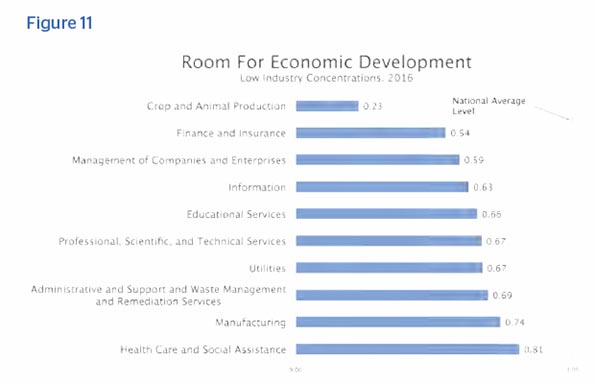

This has a lot to do with a healthy balance between job growth in all sectors of the economy with particularly strong performances in higher-growth sectors of the economy. Between 2014 and 2016, every sector of Austin’s economy added jobs, except manufacturing, which only declined by less than a percentage point. Since 2010, job growth in professional business services has grown 42 percent and information jobs by 34 percent, and over the past two years Austin has outperformed growth rates nationally in sectors diverse as wholesale trade, construction, leisure and hospitality, and retail.

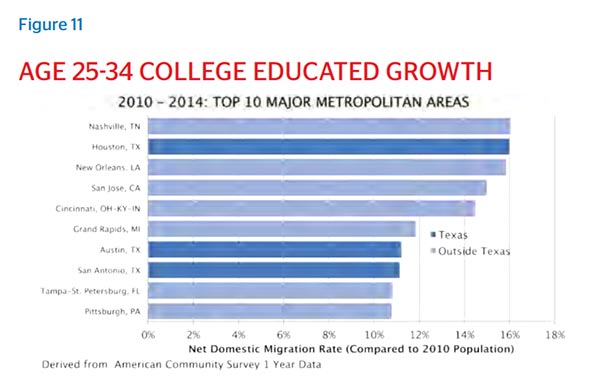

Third, an opportunity city attracts professionals on the front end of their careers. One of the best ways to test the dynamism of a region is to look at the degree to which young professionals in their 30s are moving there. Immediately after college, 20-somethings will often move to big cities to get their professional footing and enjoy the fruits of cosmopolitan living. As they approach their thirties, they begin to think about affordability more seriously and consider other opportunity-related factors such as the quality of neighborhoods and schools if they are in the marriage and-kids market. Looked at this way, Austin is the preferred destination for upwardly mobile, aspirational 30-somethings looking to make a life for themselves.

A recent Niche.com ranking of the 25 best cities for millennials used as its key metric the percentage of 25-34 year olds living in each city. Austin, which ranked second overall on the list, had the highest percentage of 25-34 year olds among the top 25 cities.

When we compare 25-34 year olds moving to the Bay Area versus Austin, we see several sharp contrasts. Between 2000 and 2014, this group grew by 49 percent in Austin but declined by nearly 4 percent in Silicon Valley. There are now more 25-34 year olds living in Austin than in the San Jose metro area.

A greater share of 25-34 year-olds in Silicon Valley have a bachelors degree than in Austin, but Austin has been growing its educated young population at a much faster rate. The 25-34 year-old population with at least a bachelors degree has grown in Austin by nearly 61 percent since 2000, compared to 18 percent in San Jose.

Balancing the Basics: Why Austin Works

Austin’s success as an opportunity city differs from what has occurred in the Bay Area’s anchor metros, San Francisco and San Jose. These places have led the nation in job creation and startups in recent years and are growing their share of highly-educated young professionals. Yet they are losing population — and company relocations — to Austin. Why is Austin succeeding where San Francisco and San Jose, at some level, are not?

The answer lies somewhere in the answers provided by those who have made the move from the Bay Area to Austin.

Vasili Triant, CEO of LiveOps, moved his company from Silicon Valley to Austin after concluding that quality of life and cost issues would keep his company from achieving its growth objectives. Before assuming the helm of LiveOps, Triant moved to the company’s Austin office to direct sales. He and his family were able to buy a home and attend schools in the kind of district that would be utterly uaffordable in the Bay Area. The easy-going yet ambitious nature of Austin’s workforce provided a solid talent pool.

Meanwhile, back in Silicon Valley, employees at Triant’s company were constantly pushing for pay raises to accommodate the cost of housing, complaining about the multiple hours a day they spent commuting, and worrying about the schools their kids would have to attend. Employees earning over $200,000 were in debt and not contributing to their 401ks.

Once he was elevated to CEO, Triant confronted his board with the built-in costs of doing business in the Bay Area. He proposed moving the company to Austin, to which the board agreed after reviewing the numbers. Triant likens the difference between the Bay Area and Austin to a difference in premise about what makes a good life worth living in each place. In Silicon Valley one gambles that he or she will make it big, has family money, or just wants to be near the ocean and the mountains. “If your premise about a good life involves saving money for the future and having a good community and school for your kids, then Austin is for you – and the Bay Area won’t be unless you’re phenomenally wealthy,” Triant says.

Pradeep Vancheeswaran, a Senior Vice President of Global Business Operations at VMWare, lived in California for his entire U.S. professional career, including seven years in the Bay Area, before moving to Austin. The cost of living and the rat-race culture of the Bay Area prompted him and his wife to reconsider whether it was the best place to raise their kids and make a life. On a scouting trip to Austin he saw the kind of home his money could buy, the kind of neighborhood he could live in, and the quality of the schools, and the decision was made. Friends said he was committing career suicide. The opposite has happened, and the family is flourishing in Austin. “Texas gets a bad rap in the Bay Area,” he says. “But the truth is Austin is an inclusive place. We have great neighbors, people are friendly, and I have been able to hire talent here with no problems. In fact, Austin ranks at the top of our global talent assessment and has been a great place to hire for our company.”

Triant’s and Vancheeswaran’s stories are not uncommon in Austin and exemplify the fundamental pillars supporting Austin’s sustained growth.

More for Your Money

Underneath the vibrant regional economy, Austin’s bedrock, not often mentioned in the hype about the city, has been its affordability.

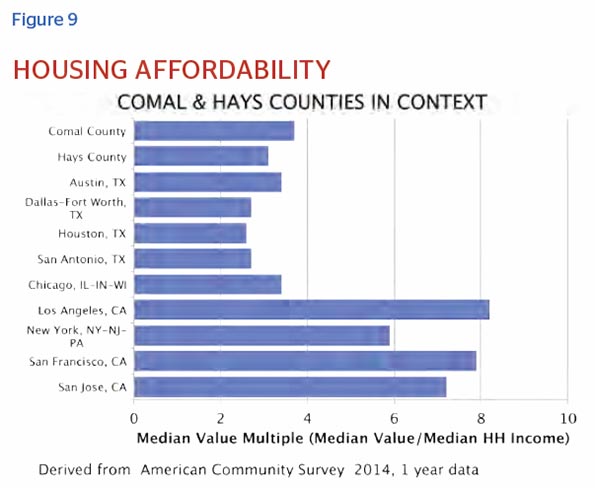

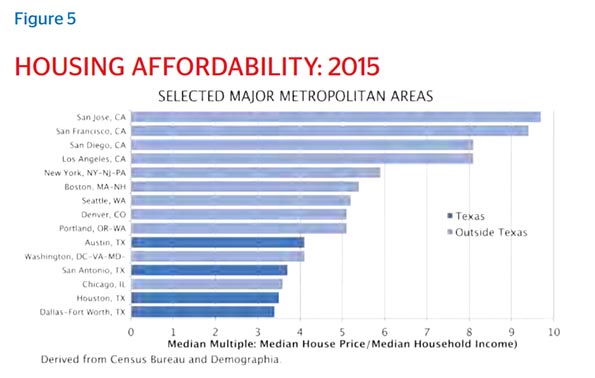

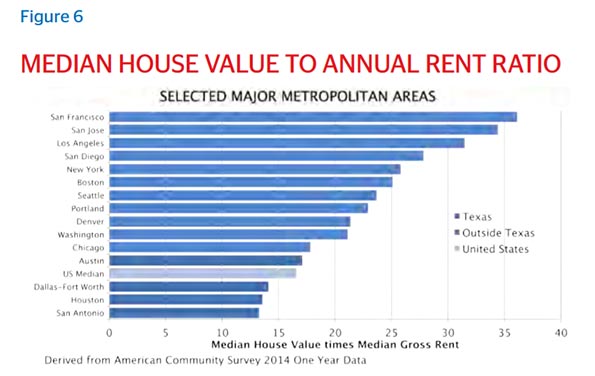

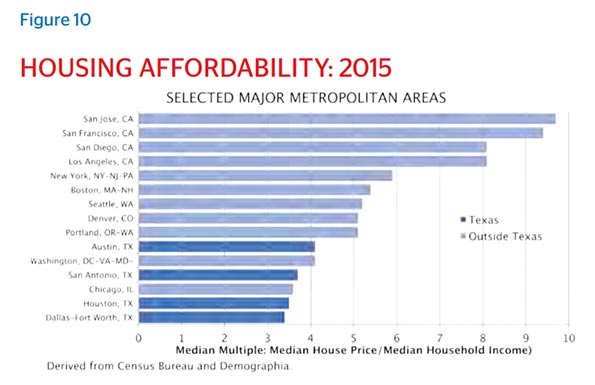

As Triant and Vancheeswaran’s personal accounts attest, Austin’s diverse and affordable housing stock is a key lure for upwardly mobile professionals. Housing in Austin is growing more expensive but still remains a reasonably good deal, particularly in comparison with the Bay Area, Los Angeles and San Diego, where housing costs more than double that of Austin, adjusted for income.

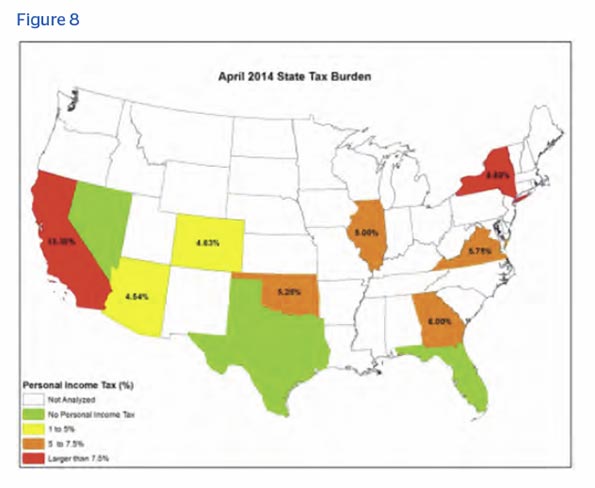

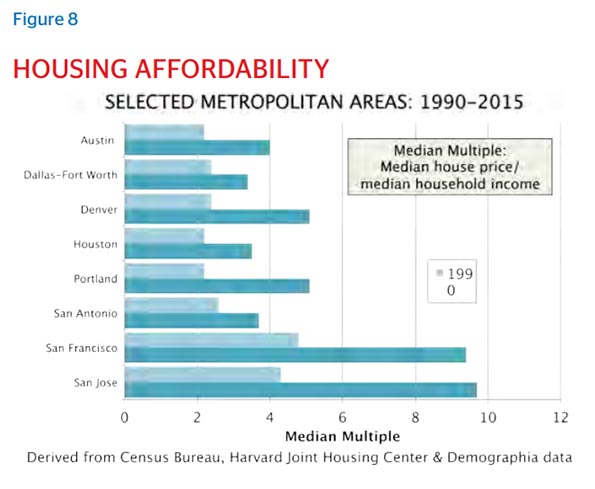

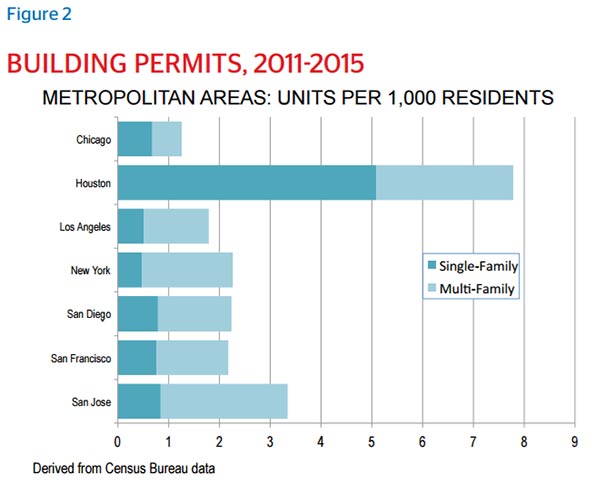

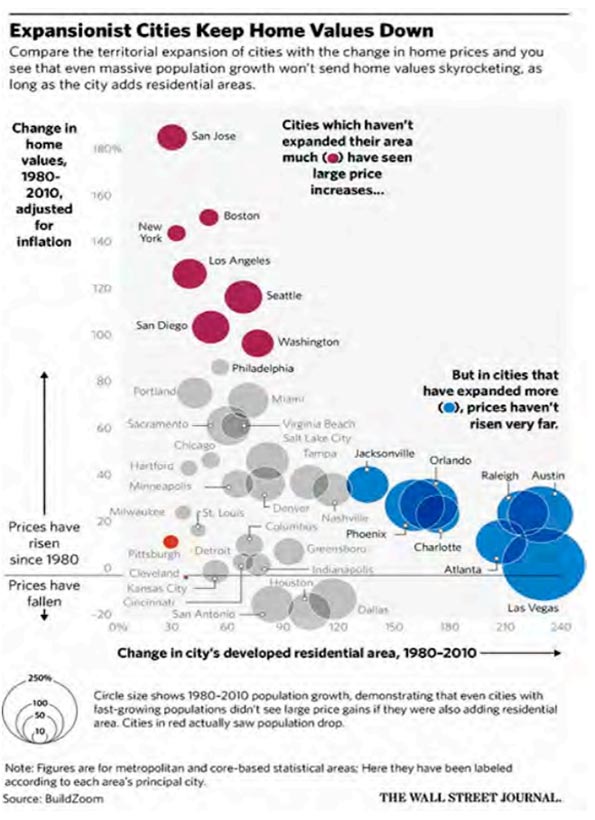

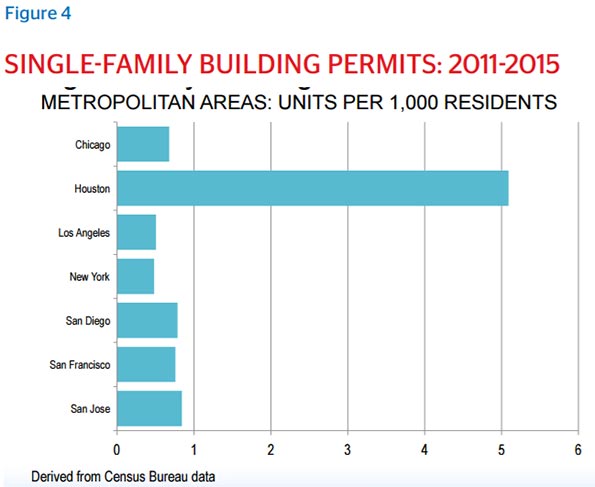

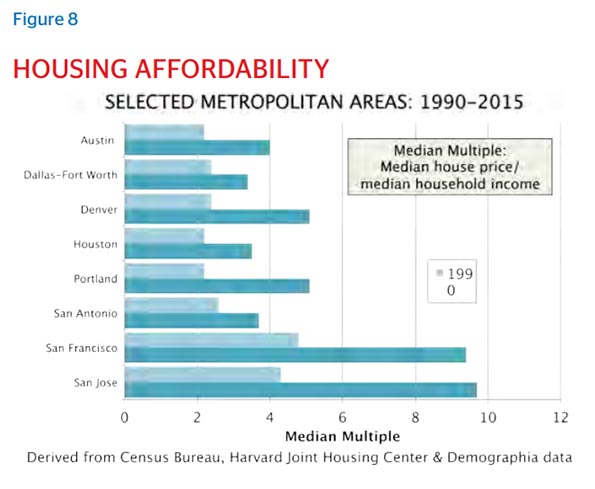

The key to maintaining housing affordability is to allow supply to keep up with demand. This requires avoiding the restrictions on suburban housing development that have been adopted in places like California, Portland and Seattle, and avoiding the high development charges typical of more restrictively regulated markets. As Figure 8 shows, affordability was nearly identical in Austin, Portland, and Denver in 1990. Since then, unaffordability has grown faster in the latter two markets, which place more restrictions on housing than Austin does. And in the Bay Area, of course, California’s notorious penchant for restricting housing is breaking records for unaffordability.

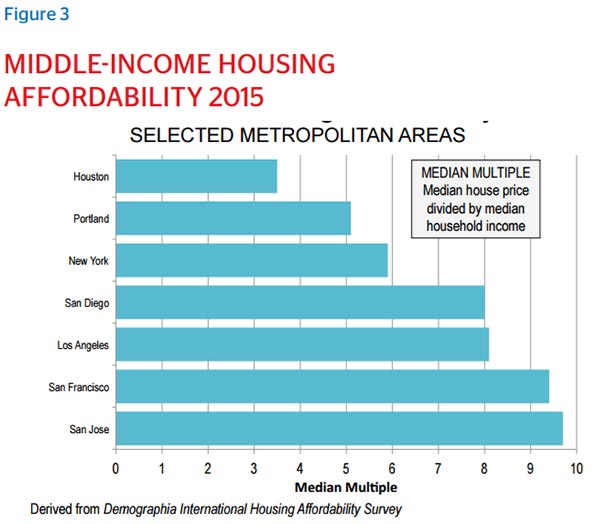

Using Demographia’s International Housing Affordability Survey, we find that single-family homes in Austin remain more affordable than rival talent centers such as Portland, Denver, Seattle, and Washington, DC. When compared to San Jose, which is the United States’ most unaffordable housing market, it is not hard to see the appeal for Bay Area technology transplants. The median house price in San Jose and San Francisco is nearly ten times the area’s median income, compared to four times in Austin. Technology executives in the Bay Area cite housing costs as the biggest threat to their continued success.

Still, at four times median income, Austin is facing the beginning of affordability problems. It has grown from an affordable to moderately unaffordable housing market since 2000 and is presently on the cusp of becoming severely unaffordable according to Demographia’s calculations. Trulia’s chief economist agrees, arguing that Austin is on the verge of denting its continued growth trajectory should housing prices climb much farther relative to income.

When it comes to total cost of living advantages, though, the story improves somewhat for Austin. According to BEA data, between 2008 and 2013 the overall cost of living actually decreased slightly in Austin even as it rose in New York and Washington, DC. Austin’s workforce enjoys a 20 percent cost advantage over residents of New York, who labor under the highest cost of living standards in the nation. Austin costs about the same as Phoenix or Orlando. The Bay Area, by contrast, is an indistinguishable percentage point more affordable than New York. Therefore, it is not surprising that San Francisco and San Jose have seen positive net migration from New York in recent years. If life must cost an unbearable amount, the weather and scenery might as well be better.

Follow the Money

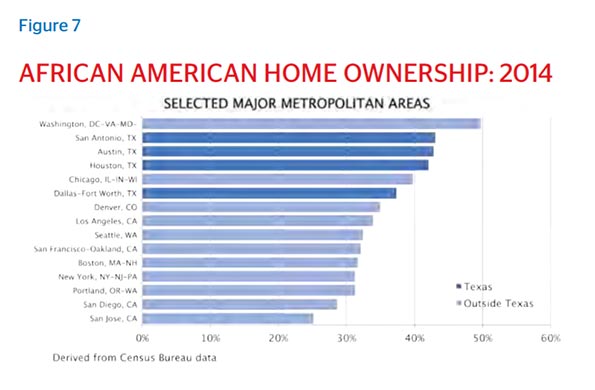

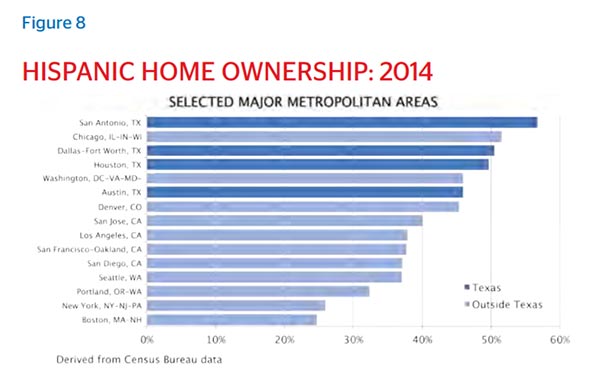

Austin’s real median income is the highest of Texas’s four largest metros and even surpasses the New York metro area. Of the nation’s 53 cities with more than one million residents, Austin’s median household income is the tenth highest adjusted for cost of living. African American and Asian median incomes in Austin are fourth and fifth respectively among the largest U.S. cities, and salaries in Austin typically track slightly above the national average for most job categories.

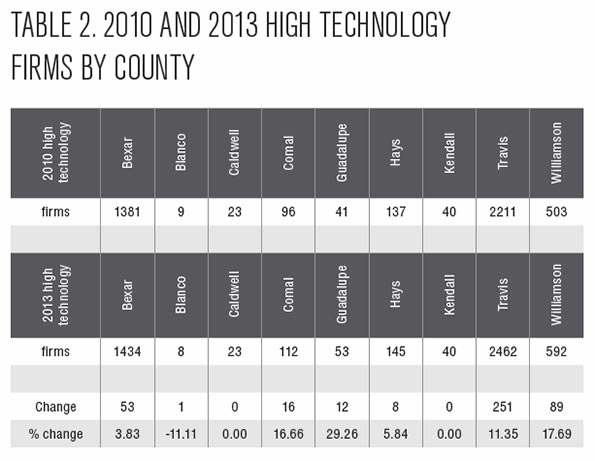

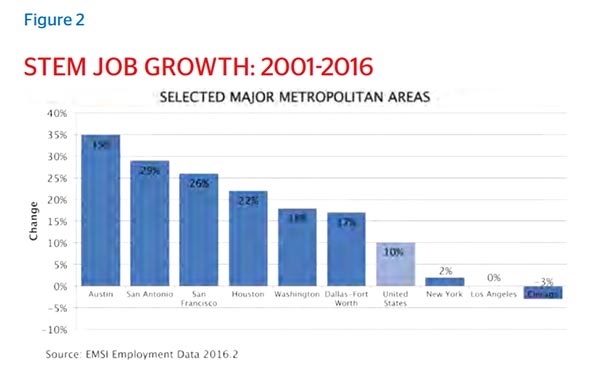

Given Austin’s emergence as a technology center , the region now has twice as many high-tech jobs as a percentage of all jobs than the national average. Nearly one-quarter of all payrolls in Austin are in the high-tech sector, with an average salary greater than $100,000, nearly double the average salary for all other industries. Though high tech salary growth has slowed in Austin in the past few years compared to the rest of the nation, the average high tech worker in Austin still earns more than the national average. Before the Great Recession, there were more high-tech manufacturing than IT jobs in Austin, but the past five years have seen an explosion of information and other IT-related high tech jobs. The number of IT jobs in Austin has nearly doubled in the past ten years, totaling more than 56,000.

High-tech manufacturing jobs remain the highest-paying, though, with an average annual salary fetching $122,000. Income growth outside of high tech jobs has grown at a faster rate than tech jobs. Between 2010 and 2015, Austin had the second-highest annual job growth across all industries at 3.7 percent, just a click behind San Francisco’s 3.8 percent growth rate. Austin’s high tech job growth rate of 5.7 percent was also the second-highest nationally, once again behind San Francisco’s peerless 10.7 percent growth rate. These rates of growth have been matched by healthy income growth that makes Austin a premier opportunity city.

Good Place for the Kids

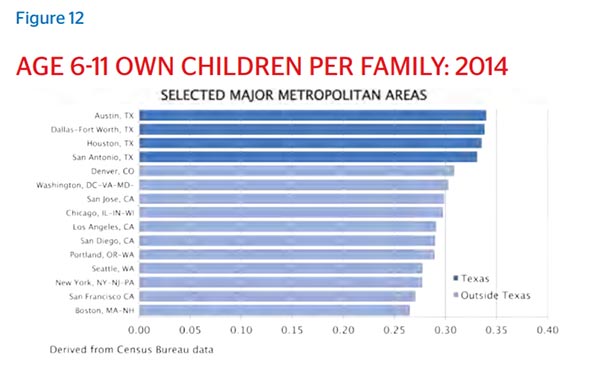

Austin’s relative affordability and earning power is buttressed by two additional factors that are especially important to families and young people planning to have children: safety and schools. As Austin has grown, the sheer influx of families with children has placed a premium on the availability of strong educational options and a safe environment.

Between 2000 and 2014, the number of households in Austin with children under the age of 18 grew 35 percent. By contrast, such households grew 4 percent in San Jose. This does not mean that Austin is necessarily more pro-family or pro-marriage in the sense of cultural norms. The percentage of married adults in Austin has declined just as it has across most urban areas in the past 15 years, as has the percentage of young couples with children.

But, as sheer volume of families with children moving to Austin in absolute terms shows, the overall environment is very family-friendly. Austin’s schools fare better on most assessments of public school quality than Texas’s other large cities, and families have public school options all across the metro area. For instance, consumer-oriented data analysis sites such as FindtheHome.com rate Austin’s city schools ten points or more ahead of Dallas, Houston, and San Antonio, and the State of Texas’s overall rankings show a substantial percentage of high-performing schools in the metro area. Whether a family chooses to live downtown or the suburbs, there are strong public school options unlike ones one would normally find in large urban areas.

An annual survey of residents shows that Austinites value choices in education as well. A majority of adults believe the public schools in Austin are a good value for their tax dollars. Yet 59 percent of 18-34-year-olds support school vouchers, as do 50 percent of adults over 35. Fifty-nine percent of all adults either send their kids to charter schools or would consider doing so. Sixty percent of respondents say they chose where to live based on school options.

Austin is also one of the safest cities in Texas. According to the FBI’s Uniform Crime Reports, Austin ranks 21 out of Texas’s 24 metro areas in the report in crime incidents, well below the other larger metros.106 As a state capital and university town Austin’s growth has “skipped over” the debasements that accompany deindustrialization and largescale losses within working-class economies. But Austin’s growth patterns, variegated and multi-nodal as they are across the metro area, have also created diverse economic centers that have prevented large swaths of the city from falling into decline.

Option Urbanism: Austin’s Polycentric Character

The thing that ultimately makes Austin’s population and economic growth work is the multi-nodal quality of the metro area’s growth. Despite its reputation as a “hip” and dense urban area, in reality Austin is a city of districts that balances and disperses urban-style amenities across its urban and suburban landscape.

Austin’s reputation as an urban hotspot is well-deserved. The Austin City Limits concert venue and annual festival are in or immediately across the Colorado River from downtown. South By Southwest, the global technology, film, and music festival, occurs mostly in venues spread across Austin’s urban core. The heart of the Austin music scene along 6th Street downtown is only a short walk from the Texas state capitol and a mere 13 blocks from the University of Texas at Austin, the state’s flagship university whose iconic tower is a fixture along the Austin skyline. Visitors to Austin over the past decade are always greeted by construction cranes that dot the downtown landscape, as high rises compete with one another to make a new mark on the skyline.

Suburban Austin

Demand for downtown living has never been higher in Austin, and yet the cranes and construction zones tend to hide the true locus of Austin’s dynamism—the area’s lively suburbs. This is where the vast majority of the region’s population growth in the past 15 years has occurred. Not merely appendages to downtown, Austin’s suburban communities have done a notable job of incorporating elements of the city’s urban identity into the quality of life its suburban residents experience. One can find food trucks, coffee shops, new restaurants, indie shops of various kinds, music, and festivals dispersed across the metro area. The Barton Creek Greenbelt that stretches southwest off the Colorado River downtown spreads outdoor recreational opportunities, for which Austin is also well-known, across multiple access points through a variety of neighborhoods.

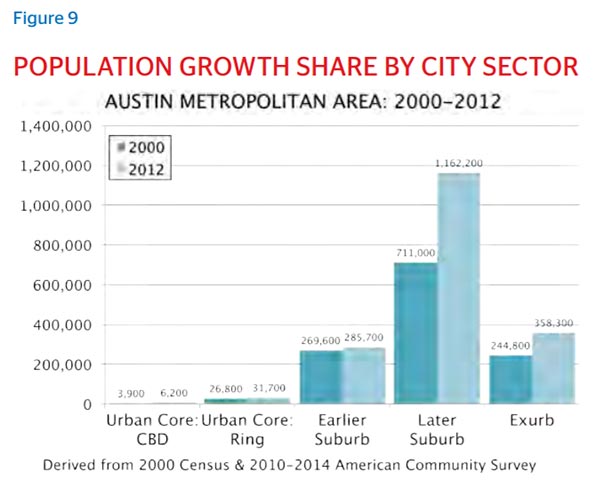

In 1990, when Austin metro’s population was less than one million, 45 percent of residents lived in the suburbs. Today, 53 percent of Austinites live in the suburbs. The city grew 47 percent between 1990 and 2000, and then another 37 percent between 2000 and 2010. The vast majority of this growth has been suburban in nature.

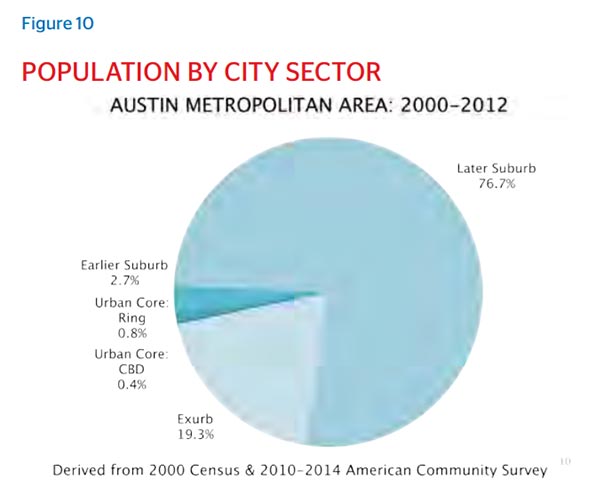

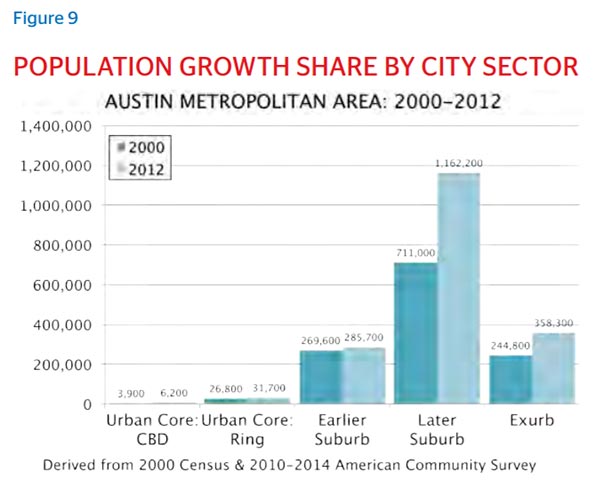

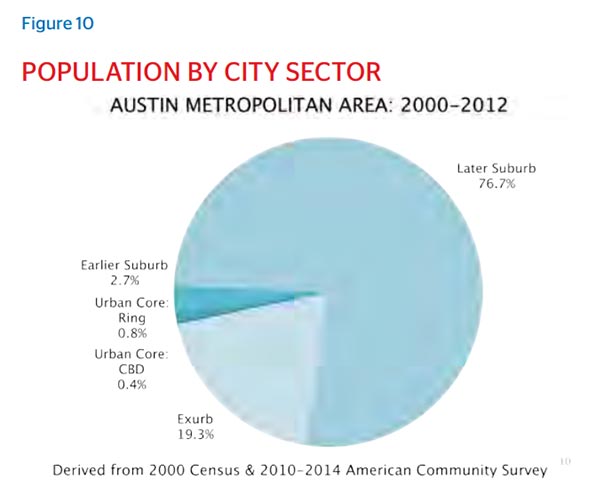

Using Demographia’s City Sector Model, we see the urban core and urban core’s ring, defined as the central business district and original downtown ring pre-dating World War II, experienced healthy rates of growth but added little in absolute terms between 2000 and 2012. What most people think of as today’s booming downtown Austin only accounted for 1.6 percent to the metro area’s entire growth during this period. Of the 588,000 new residents to Austin during this period, 564,700 of them moved into suburban neighborhoods.

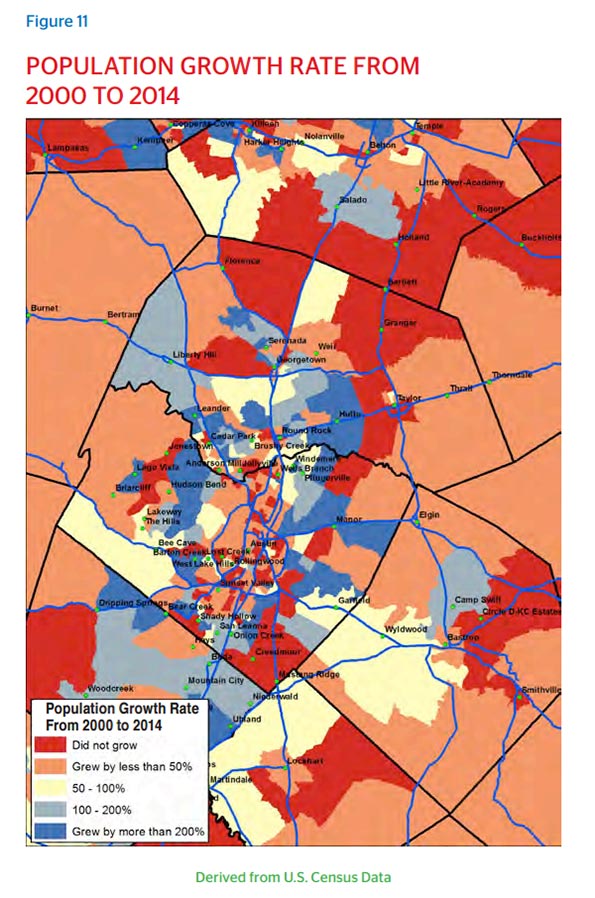

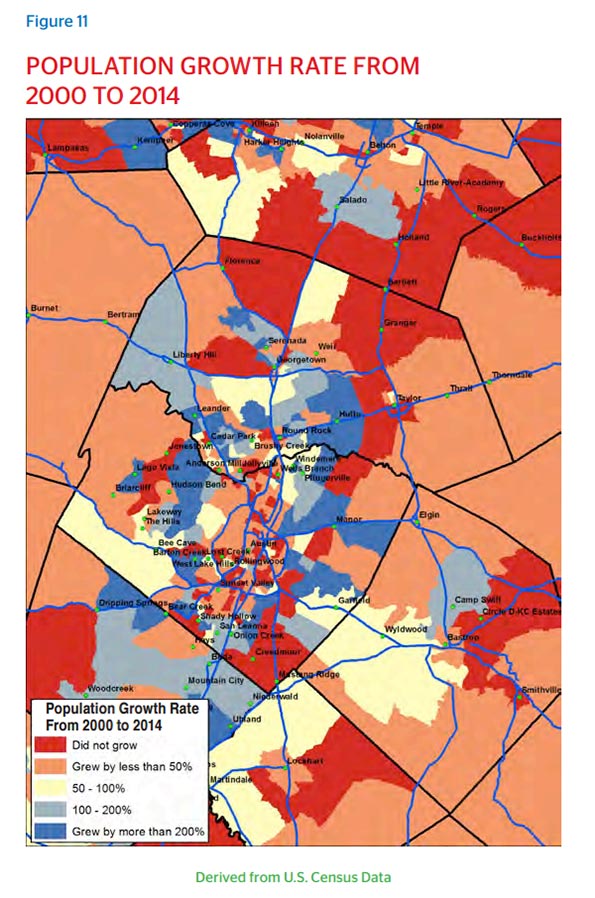

Figure 11 shows how this growth looks geographically. Central Austin grew very little between 2000 and 2014. The fastest growth, depicted by the grey and blue areas, is largely suburban.

Homeownership in Austin follows this suburban trajectory. Compared to 30 percent among the nation’s 52 largest metro areas, 62 percent of the owned housing stock in Austin can be found in suburbs in which the median home construction year was after 1980. That figure is less than 10 percent in Silicon Valley. By contrast, 77 percent of owned housing in Silicon Valley is in older suburbs with a median home construction year before 1980, compared to 14 percent in Austin and 41 percent nationally. Another 23 percent of Austin’s owned housing is located in exurban communities, compared to 19 percent nationally and 13 percent in Silicon Valley.

Austin’s success as an urban model is closely tied to its ability to meet population demand with new housing in new communities. The increasing difficulty to build and afford housing in the Bay Area is effectively making homeownership a phenomenon of aging suburban communities, as greater shares of aspiring homeowners leave the area altogether, as seen earlier.

Multi-Nodal Tech City

Austin’s suburban expansion also dominates much of the economy. Nearly half – 43 percent – of tech jobs are in the suburbs and much of the rest in areas outside downtown. Local markets for urban-style amenities such as bars, cafes, and events have arose to meet the demand of a highly-educated, relatively young workforce that nonetheless prefers lower-density suburban living. This creates a district effect that has worked relatively well with Austin’s zoning codes and allowed for either mixed-use, or regional mixes of uses, in various points across the metro area.

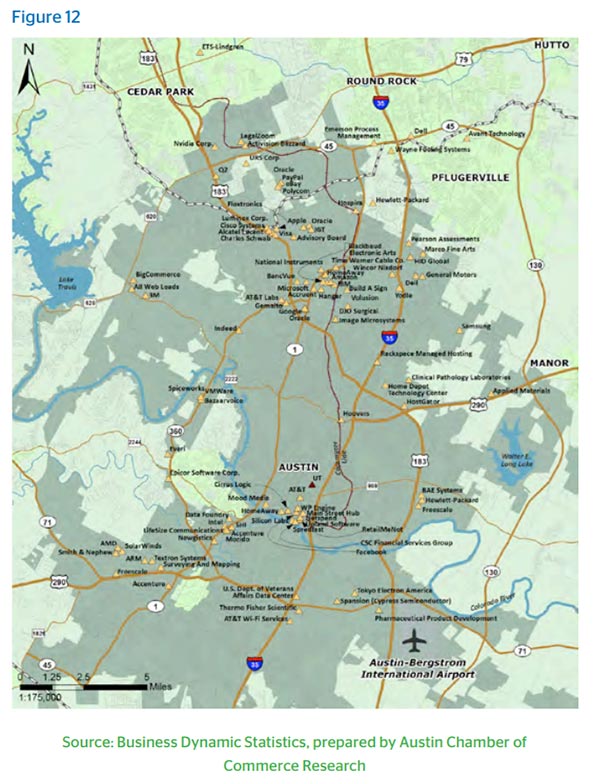

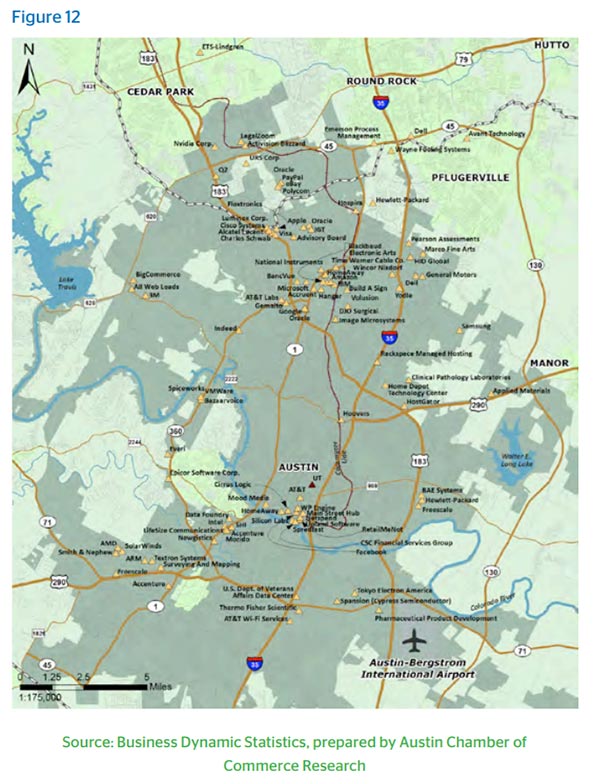

Figure 12, an Austin Chamber of Commerce map of the city’s 100 largest high-tech companies, paints a picture of a multi-nodal tech community that is both urban and suburban. Since 2014, 37 percent of high-tech companies that have moved to Austin have relocated downtown, while the rest are dispersed across the various hubs.

The heavily concentrated hub downtown and the corridor stretching southwest of downtown offer a diverse array of living options. South Austin interweaves leafy residential neighborhoods around its three north-south district roadways: South Congress, South First, and South Lamar. To the west are rolling, leafy suburban-style communities that offer proximity to downtown. Downtown increasingly offers dense, high-rise living with ample amenities. The Bartin Creek Greenbelt and trails around Lady Bird Lake (created by two dams in the Colorado River) are the centerpieces of Austin’s esteemed outdoor fitness culture.

Between downtown and the concentration of tech firms along and north of route 183 are patchworks of neighborhoods and districts that blend homes, apartments, restaurants, shops and bars, once again creating options for families and single workers. The Domain, the mixed use complex near the intersection of Routes 1 (Mopac) and 183, is beginning to serve as a kind of “city center” north of downtown. Suburban neighborhoods west, north, and east of the northern tech hub offer an array of suburban options for families and workers. Apple is completing its second-largest campus outside of its California headquarters in the community, and other tech giants such as Google and Oracle have nearby offices.

Dell anchors the tech community in Round Rock to the north, which effectively functions as a separate city center. Round Rock, with a population of more than 100,000, has more than tripled in size since 1990. Dell employs more than 13,000.

Austin’s rapid growth, coupled with lagging investments in transportation infrastructure, accounts for why Austinites frequently rank traffic congestion as the biggest problem facing the city. Viewed comparatively, however, average work commute times in Austin match the national average at 25.5 minutes one way, compared to 31.2 minutes in San Francisco and 28.1 minutes in San Jose. Atlanta’s car commute times take a full five minutes longer than Austin’s, and in Washington, DC, an extra ten. Overall, Austin’s average commute times – whether by car, transit, bike or foot – is on part with Indianapolis or Charlotte. For transplants from New York or the Bay Area, commutes are likely to contribute to Austin’s appeal rather than the other way around. Car commute times are lower in Austin than either of those areas, as one might expect, but so are walk-to-work times.

Despite this relatively good performance, over time traffic congestion along with housing affordability could begin to chip away at the city’s magnetic appeal. But for now, despite the frequent grousing one hears from locals about the traffic, Austinites on average are not worse off than other Americans living in cities larger than 1 million people.

Austin’s still reasonable commute times reflect the polycentric quality of its economic geography. With commercial and cultural locations spread across the metro area, together with an array of single- and multi-family housing options nearby, Austin offers choices. If a young professional couple wants a single family home with a yard, proximity to restaurants and shops and good schools, they have options. If they want to live in more of a mixed-use apartment community close to work, they have options. Downtown living is increasingly becoming harder for people not commanding top salaries, but it still remains an option for young workers that other cities do not offer.

Conclusion

Austin is well-known as a talent center, but students of urbanism would do well to study the geographic nature of the talent economy in Texas’s capital. It is a dispersed talent pool, spread across a relatively affordable metro area with proximity to urban-style amenities.

Austin has managed to encourage and allow the concurrent development of its central core and inner and outer rings in a way that has made variety a central feature of the Austin model. People, young and old, have options in Austin. Good schools can be found across the metro area meaning people rarely have to sacrifice amenity preferences in order to live close to a good school, which is a conventional understanding of what “moving to the ‘burbs” often entails in most cities.

Austinites have work options, too, in two ways. The diverse economy, with a high proportion of high tech and other educated workers, offers opportunities in the job market for workers who decide what they are doing is not the right fit for them. Workers also have choices where they work. The polycentric nature of Austin’s commercial hubs makes this possible.

And even as affordability problems present unprecedented challenges to Austin, the city still offers alternatives for where people want to live. Because of the timing and trajectory of Austin’s population growth, a lot of new housing is available, as well.

The key to the Austin model’s continued success will be to preserve its core features as an opportunity city and the fundamentals that have made it work until now. Over-planning or limiting growth, concentrating economic strength in too few places, allowing school quality to erode – these are precisely the things that have done significant damage to other previously successful cities in America. Austin’s strength has been in going in the other direction. Its continued success depends upon continuing along the same path it has traveled until now, but with a vision to accommodate what seems as inevitable greater growth.

Ryan Streeter is the Executive Director of the Center for Politics and Governance at the University of Texas at Austin and Clinical Professor of Public Policy at the LBJ School of Public Affairs. Streeter has conducted policy research projects for think tanks, institutional nonprofits, and public agencies at the federal, state, and local levels. He served as a Special Assistant for Domestic Policy to President George W. Bush, Deputy Chief of Staff for Policy and Strategy to Indiana Governor Mike Pence, and Policy Advisor to Indianapolis Mayor Stephen Goldsmith. He was a Senior Fellow at the Legatum Institute in London, has served as a Transatlantic Fellow with the German Marshall Fund, and was a Research Fellow at the Hudson Institute.

Top photo: Photo by jdeeringdavis, Licensed under CC License