Demographers frequently remind us that the United States is a rapidly aging country. From 2010 to 2040, we expect that the age-65-and-over population will more than double in size, from about 40 to 82 million. More than one in five residents will be in their later years. Reflecting our higher life expectancy, over 55% of this older group will be at least in their mid-70s.

While these numbers result in lively debates on issues such as social security or health care spending, they less often provoke discussion on where our aging population should live and why their residential choices matter.

But this growing share of older Americans will contribute to the proliferation of buildings, neighborhoods and even entire communities occupied predominantly by seniors. It may be difficult to find older and younger populations living side by side together in the same places. Is this residential segregation by age a good or a bad thing?

As an environmental gerontologist and social geographer, I have long argued that it is easier, less costly, and more beneficial and enjoyable to grow old in some places than others. The happiness of our elders is at stake. In my recent book, Aging in the Right Place, I conclude that when older people live predominantly with others their own age, there are far more benefits than costs.

Why do seniors tend to live apart from other age groups?

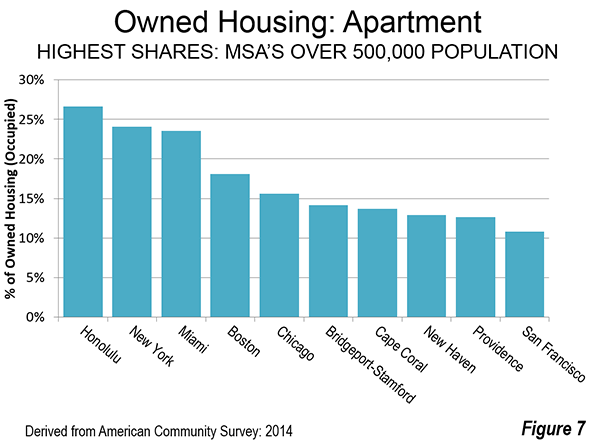

My focus is on the 93% of Americans age 65 and older who live in ordinary homes and apartments, and not in highly age-segregated long-term care options, such as assisted living properties, board and care, continuing care retirement communities or nursing homes. They are predominantly homeowners (about 79%), and mostly occupy older single-family dwellings.

Older Americans don’t move as often as people in other age groups. Typically, only about 2% of older homeowners and 12% of older renters move annually. Strong residential inertiaforces are in play. They are understandably reluctant to move from their familiar settings where they have strong emotional attachments and social ties. So they stay put. In the vernacular of academics, they opt to age in place.

Over time, these residential decisions result in what are referred to as “naturally occurring” age-homogeneous neighborhoods and communities. These residential enclaves of old are now found throughout our cities, suburbs and rural counties. In some locales with economies that have changed for the worse, these older concentrations are further explained by the wholesale exit of younger working populations looking for better job prospects elsewhere – leaving the senior population behind.

Even when older people decide to move, they often avoid locating near the young. The Fair Housing Amendments Act of 1988 allows certain housing providers to discriminate against families with children. Consequently, significant numbers of older people can move to these “age-qualified” places that purposely exclude younger residents. The best-known examples are those active adult communities offering golf, tennis and recreational activities catering to the hedonistic lifestyles of older Americans.

Others may opt to move to “age-targeted” subdivisions (many gated) and high-rise condominiums that developers predominantly market to aging consumers who prefer adult neighbors. Close to 25% of age-55-and-older households in the US occupy these types of planned residential settings.

Finally, another smaller group of relocating elders transition to low-rent senior apartment buildings made possible by various federally and state-funded housing programs. They move to seek relief from the intolerably high housing costs of their previous residences.

Is this a bad thing?

Those advocates who bemoan the inadequate social connections between our older and younger generations view these residential concentrations as landscapes of despair.

In their perhaps idyllic worlds, old and young generations should harmoniously live together in the same buildings and neighborhoods. Older people would care for the children and counsel the youth. The younger groups would feel safer, wiser and respectful of the old. The older group would feel fulfilled and useful in their roles of caregivers, confidants and volunteers. In question is whether these enriched social outcomes merely represent idealized visions of our pasts.

A less generous interpretation for why critics oppose these congregations of old is that they make the problems faced by an aging population more visible and thus harder to ignore.

Residents play shuffleboard at Limetree Park in Bonita Springs, Florida. Steve Nesius/Reuters

Residents play shuffleboard at Limetree Park in Bonita Springs, Florida. Steve Nesius/Reuters

A better social life

But why should we expect older people to live among younger generations? Over the course of our lives, we typically gravitate to others who are at similar stages in life as ourselves. Consider summer camps, university dormitories, rental buildings geared to millennials or neighborhoods with lots of young families. Yet we seldom hear cries to break up and integrate these age-homogeneous residential enclaves.

In fact, studies show that when older people reside with others their age, they have more fulfilled and enjoyable lives. They do not feel stigmatized when they practice retirement-oriented lifestyles. Even the most introverted or socially inactive older adults feel less alone and isolated when surrounded with friendly, sympathetic, and helpful neighbors with shared lifestyles, experiences, and values – and yes, who offer them opportunities for intimacy and an active sex life.

Moreover, tomorrow’s technology is especially on the side of these elders. Because of online social media communications, older people can engage with younger people – as family members, friends, or as mentors – but without having to live next to what they sometimes feel are noisy babies, obnoxious adolescents, indifferent younger adults or insensitive career professionals.

Age-specific enclaves prolong independent living

Could living in these age-homogeneous places help older people avoid a nursing home stay?

Studies say yes – because here they have more opportunities to cope with their chronic health problems and impairments. Now their greater visibility as vulnerable consumers becomes a plus because both private businesses and government administrators can more easily identify and respond to their unmet needs.

These elder concentrations spawn a different mindset. The emphasis shifts from serving troubled individual consumers to serving vulnerable communities or “critical masses” of consumers.

Consider how many more clients home-care workers can assist when they are spared the traveling time and costs of reaching addresses spread over multiple suburbs or rural counties. Or recognize how much easier it is for a building management or homeowners’ association to justify the purchasing of a van to serve the transportation needs of their older residents or to establish an on-site clinic to address their health needs.

Consider also the challenges confronted by older people seeking good information about where to get help and assistance. Even in our internet age, they still mostly rely on word of mouth communications from trusted individuals. It becomes more likely that these knowledgeable individuals will be living next to them.

These enclaves of old have also been the catalyst for highly regarded resident-organizedneighborhoods known as elder villages.

Their concerned and motivated older leaders hire staff and coordinate a pool of their older residents to serve as volunteers. For an annual membership fee, the predominantly middle-income occupants in these neighborhoods receive help with their grocery shopping, meal delivery, transportation and preventive health needs. Residents also benefit from knowing which providers and vendors (like workers performing home repair) are the most reliable, and they often receive discounted prices for their goods and services. They also enjoy organized educational and recreational events enabling them to enjoy the company of other residents. Today, about such 170 villages are open and 160 are in planning stages.

A question of preference

Ageist values and practices are indeed deplorable. However, we should not view the residential separation of the old from the young as necessarily harmful and discriminatory but rather as celebrating the preferences of older Americans and nurturing their ability to live happy, dignified, healthy and autonomous lives. Living with their age-peers helps these older occupants compensate for other downsides in their places of residence and in particular presents opportunities for both private and public sector solutions.

Tihs piece was first published by The Conversation.

Stephen M. Golant, Ph.D, a gerontologist and geographer, is now a Professor in the Department of Geography at the University of Florida. Previously, he was a faculty member in the Committee on Human Development and in the Department of Geography at the University of Chicago. Dr. Golant has been conducting research on the housing, mobility, transportation, and long-term care needs of older adult populations for most of his academic career. He is a Fellow of the Gerontological Society of America and a Fulbright Senior Scholar award recipient. He earlier served as a consultant to the Congressionally appointed Commission on Affordable Housing and Health Facility Needs for Seniors in the 21st Century (Seniors Commission). He has written or edited about 140 papers and books. His latest book is Aging in the Right Place (Health Professions Press, 2015).

Laed photo by Steve Nesius/Reuters.

Residents play shuffleboard at Limetree Park in Bonita Springs, Florida. Steve Nesius/Reuters

Residents play shuffleboard at Limetree Park in Bonita Springs, Florida. Steve Nesius/Reuters