Cities get ranked in numerous ways — by income, hipness, tech-savviness and livability — but there may be nothing more revealing about the shifting fortunes of our largest metropolitan areas than patterns of domestic migration.

Bright lights and culture may attract some, but people generally move to places with greater economic opportunity and a reasonable cost of living, particularly affordable housing.

So who moves? Census data suggests that it is primarily the young — those aged 25 to 34 — followed by people approaching retirement. Family and friends are a big motivating factor in both age groups. According to the moving company Mayflower, one in four millennials aged 18 and 34 moved back to their hometowns over the past five years. At the same time seniors also express a strong desire to live close to their children and grandchildren; most elderly who do not make such moves age in place.

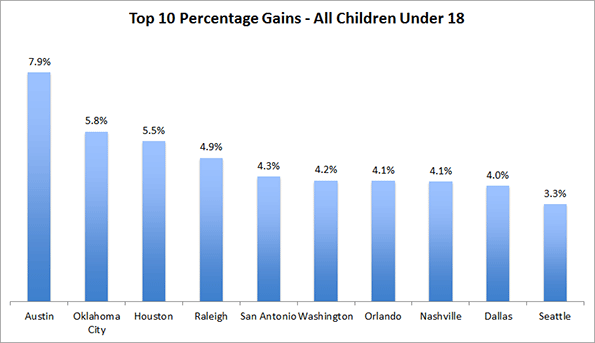

Forbes took a close look at the most recent data on domestic migration — that is movement within the U.S. between metro areas — between 2010 and 2014. We ranked the nation’s 53 largest metropolitan areas based on their annualized rates of population change attributable to migration. What we found is that to a remarkable extent, Americans still seem to be whistling Dixie. Eight of the 10 fastest gainers were in the former Confederacy, led by Austin, Texas, which gained 126,296 more migrants over that time span from other parts of the country than it lost in outmigration, accounting for an annual increase in its population of 1.69%. No other metro area in the country enjoyed anything like this rate of in-migration.

Austin’s high job creation rate — over 3% growth annually since 2010 — has a great deal to do with its ability to lure new residents not only from other Texas cities, but from the coasts as well.

The other Southern standouts are from the northern and western edges of the region. They include several Texas cities — No. 3 San Antonio (1.02% annual increase in population from migration) and No. 8 Houston — which have logged strong job growth and offer housing prices, adjusted for incomes, that are less than half those in coastal California, New York and parts of New England.

The oil bust could slow down the allure of some of these cities, notably Houston as well as No. 9 Oklahoma City. But lower petroleum prices could prove a boon to nearly universally suburbanized cities such as No. 2 Raleigh, N.C. (1.14% annual growth in population from migration), and No. 5 Nashville, Tenn., both of which have economies built around technology, manufacturing and business services. Raleigh is growing so strongly that local officials expect the population of the metro area will double over the next 20 years.

It’s a continuation of a longstanding shift to the South, a trend that some pundits were quick to declare was over after the Great Recession amid a perceived rise in interest in urban living. There have certainly been some Southern metro areas that seem to have lost appeal since 2010, notably Atlanta, Tampa-St. Petersburg and Jacksonville, all of whose rates of in-migration have slowed, although they’re still comfortably among the 20 top destinations.

The Rockies And The Pacific Northwest

In this century, the other great migration draw has been two parts of the West: the Mountain States and the Pacific Northwest. This vast region extending from Colorado to Oregon has enjoyed generally strong economic growth and reasonable housing costs, particularly in comparison with coastal California. The big winner here has been No. 4 Denver, which gained a net 103,785 domestic migrants from 2010 to 2014.

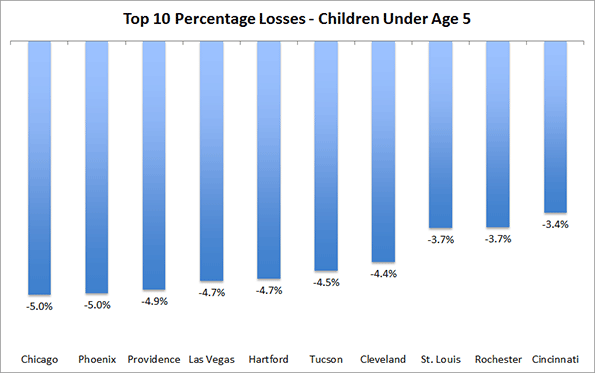

The other strong performers in the region include No. 11 Phoenix, which gained 119,000 net migrants since 2010. But this is a slowdown from its previous pace; between 2000 and 2009 (the Census Bureau did not produce migration figures for 2009-2010), Phoenix ranked fifth in the nation. But an even bigger decline has occurred in Las Vegas, the boomtown of the last decade, which has fallen from the No. 2 in the first decade of the new millennium to 16th place in 2010-14. On an annual basis, Las Vegas is now attracting about 9,000 net migrants a year compared to 35,000 in the 2000s.

The Pacific Northwest continues to attract more migrants than it loses, many from California. The big winner here has been No. 15 Seattle, which has gained 60,000 net migrants since 2010; in the last decade, the Emerald City barely managed 40,000 net migrants from 2000 to 2009. Portland has added about 49,000 net migrants, though its annual inflow has dropped somewhat.

Winners And Losers

It is frequently claimed by fiscal conservatives that politics and regulation drive these patterns. Generally speaking, there tends to be more growth in lower-tax states than in higher-taxed ones, but this analysis only goes so far. Blue metro areas like Seattle, Portland and Denver are luring new residents despite somewhat higher costs and stringent regulation. It seems likely that their success is that they are not California, a regulatory state on steroids.

Indeed economic booms can make up for a lot of sins. No. 20 San Francisco may not be drawing newcomers like an Austin or a Nashville, but super-high costs have not been enough to overcome the lure of riches from the current tech boom. Since 2010, the area, which includes suburban San Mateo County, Marin County and the East Bay, has attracted a net 49,000 new migrants, a big turnaround compared to the massive outflow of 347,000 suffered in the first decade of this millennium.

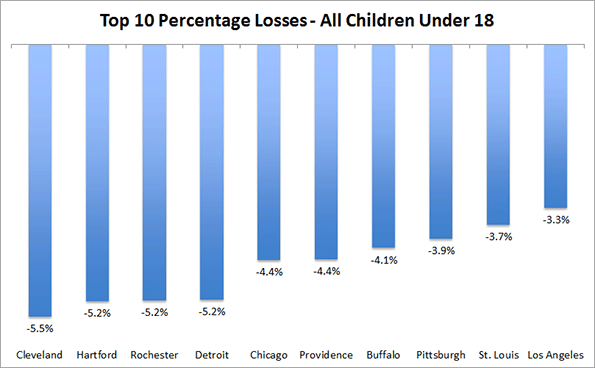

But other expensive and expansive metropolitan areas are not doing as well in the population sweepstakes. The nation’s three largest metropolitan areas fall to the bottom of our list: Los Angeles (46th), Chicago (52nd) and, in last place New York. Since 2010, the New York metro area has lost a net 529,000 domestic migrants, adding to the 1.9 million who departed from 2000 to 2009.

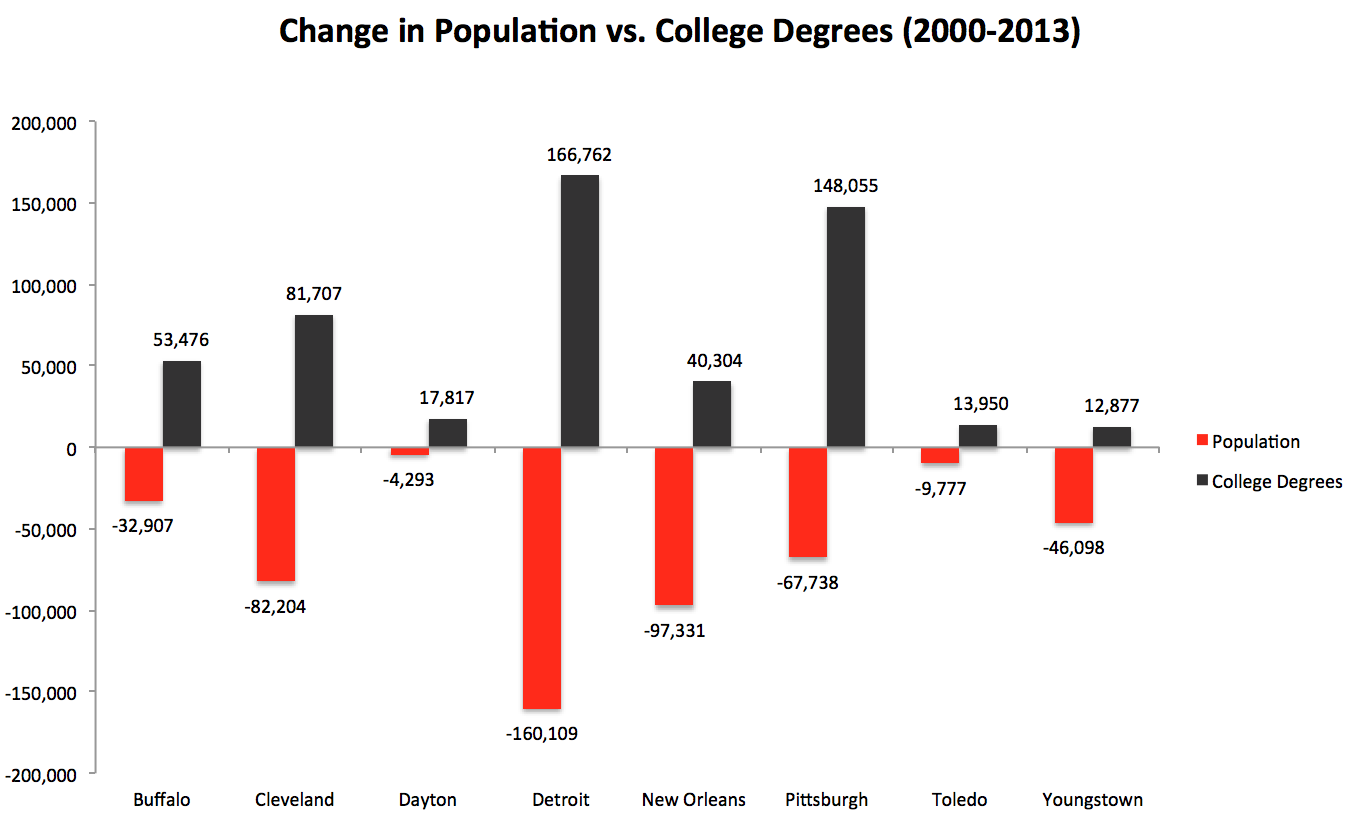

Yet these great metropolitan areas are not shrinking, due to a steady flow of new residents from overseas and a surplus of births over deaths. In this sense, they are less vulnerable to migration losses than cities such as Cleveland, Pittsburgh and Detroit, where the rate of domestic outmigration is lower, but the number of new foreign immigrants is relatively low.

Clearly America’s migration trends are always changing, but for the most part the basics remain the same. Places that are more affordable, and also have thriving economies, tend to attract new residents while those with relatively tepid economies and high costs fare, all things being equal, far worse.

The Winners: No. 1: Austin, Texas

Metro Area Population, 2014: 1.94 million

Net Domestic Migration Gain, 2010-14: 126,296

Annual Rate Of Pop. Increase Since 2010 From Migration: 1.69%

No. 2: Raleigh, NC

Metro Area Population, 2014: 1.24 million

Net Domestic Migration Gain, 2010-14: 55,920

Annual Rate Of Pop. Increase Since 2010 From Migration: 1.14%

No. 3: San Antonio, TX

Metro Area Population, 2014: 2.33 million

Net Domestic Migration Gain, 2010-14: 94,159

Annual Rate Of Pop. Increase Since 2010 From Migration: 1.02%

No. 4: Denver, CO

Metro Area Population, 2014: 2.75 million

Net Domestic Migration Gain, 2010-14: 103,785

Annual Rate Of Pop. Increase Since 2010 From Migration: 0.95%

No. 5: Nashville, TN

Metro Area Population, 2014: 1.79 million

Net Domestic Migration Gain, 2010-14: 63,477

Annual Rate Of Pop. Increase Since 2010 From Migration: 0.88%

No. 6: Charlotte, NC-SC

Metro Area Population, 2014: 2.38 million

Net Domestic Migration Gain, 2010-14: 83,305

Annual Rate Of Pop. Increase Since 2010 From Migration: 0.87%

No. 7: Orlando, FLA

Metro Area Population, 2014: 2.32 million

Net Domestic Migration Gain, 2010-14: 72,735

Annual Rate Of Pop. Increase Since 2010 From Migration: 0.79%

No. 8: Houston, TX

Metro Area Population, 2014: 6.49 million

Net Domestic Migration Gain, 2010-14: 191,796

Annual Rate Of Pop. Increase Since 2010 From Migration: 0.75%

No. 9: Oklahoma City, OK

Metro Area Population, 2014: 1.34 million

Net Domestic Migration Gain, 2010-14: 37,528

Annual Rate Of Pop. Increase Since 2010 From Migration: 0.70%

No. 10: Dallas-Fort Worth, TX

Metro Area Population, 2014: 6.95 million

Net Domestic Migration Gain, 2010-14: 184,021

Annual Rate Of Pop. Increase Since 2010 From Migration: 0.67%

The Losers: No. 10: Milwaukee, WI

Metro Area Population, 2014: 1.57 million

Net Domestic Migration Loss, 2010-14: 22,597

Annual Rate Of Pop. Decrease Since 2010 From Migration: -.34%

o. 9: Virginia Beach-Norfolk, VA-NC

Metro Area Population, 2014: 1.72 million

Net Domestic Migration Loss, 2010-14: 24,374

Annual Rate Of Pop. Decrease Since 2010 From Migration: -.34%

No. 8: Los Angeles, CA

Metro Area Population, 2014: 13.26 million

Net Domestic Migration Loss, 2010-14: 208,635

Annual Rate Of Pop. Decrease Since 2010 From Migration: -.39%

No. 7: Rochester, NY

Metro Area Population, 2014: 1.08 million

Net Domestic Migration Loss, 2010-14: 17,665

Annual Rate Of Pop. Decrease Since 2010 From Migration: -.39%

No. 6: Memphis, TN-MS-AR

Metro Area Population, 2014: 1.34 million

Net Domestic Migration Loss, 2010-14: 21,999

Annual Rate Of Pop. Decrease Since 2010 From Migration: -.39%

No. 5: Cleveland, OH

Metro Area Population, 2014: 2.06 million

Net Domestic Migration Loss, 2010-14: 38,424

Annual Rate Of Pop. Decrease Since 2010 From Migration: -.44%

No. 4: Detroit, MI

Metro Area Population, 2014: 4.30 million

Net Domestic Migration Loss, 2010-14: 89,649

Annual Rate Of Pop. Decrease Since 2010 From Migration: -.50%

No. 3: Hartford, CT

Metro Area Population, 2014: 1.21 million

Net Domestic Migration Loss, 2010-14: 27,425

Annual Rate Of Pop. Decrease Since 2010 From Migration: -.54%

No. 2: Chicago, IL-IN-WI

Metro Area Population, 2014: 9.55 million

Net Domestic Migration Loss, 2010-14: 237,666

Annual Rate Of Pop. Decrease Since 2010 From Migration: -.60%

No. 1: New York, NY-NJ-PA

Metro Area Population, 2014: 20.09 million

Net Domestic Migration Loss, 2010-14: 528,742

Annual Rate Of Pop. Decrease Since 2010 From Migration: -.64%

This piece first appeared at Forbes.

Joel Kotkin is executive editor of NewGeography.com and Roger Hobbs Distinguished Fellow in Urban Studies at Chapman University, and a member of the editorial board of the Orange County Register. He is also executive director of the Houston-based Center for Opportunity Urbanism. His newest book, The New Class Conflict is now available at Amazon and Telos Press. He is also author of The City: A Global History and The Next Hundred Million: America in 2050. He lives in Orange County, CA.

Wendell Cox is Chair, Housing Affordability and Municipal Policy for the Frontier Centre for Public Policy (Canada), is a Senior Fellow of the Center for Opportunity Urbanism (US), a member of the Board of Advisors of the Center for Demographics and Policy at Chapman University (California) and principal of Demographia, an international public policy and demographics firm.He is co-author of the “Demographia International Housing Affordability Survey” and author of “Demographia World Urban Areas” and “War on the Dream: How Anti-Sprawl Policy Threatens the Quality of Life.” He was appointed to three terms on the Los Angeles County Transportation Commission, where he served with the leading city and county leadership as the only non-elected member. He served as a visiting professor at the Conservatoire National des Arts et Metiers, a national university in Paris.