Portland has been among the world leaders in urban containment policy. And, as would be predicted by basic economics, Portland has also suffered from serious housing cost escalation, as its median multiple (median house price divided by median household income) has risen from a normal 3.0 in 1995 to 4.8 in 2014.

One of the all too predictable effects of urban containment policy is at least some households will drive even farther to "qualify" for mortgages than before. Single-family detached houses have been the national preference in housing in the United States (and a number of other nations) for decades. Significant "leakage" can occur as people skip over the urban growth boundaries, inside of which housing has become unaffordable. For example, after the 2010 census, San Joaquin County, with its seat of Stockton, was added to the San Francisco Bay combined statistical area (CSA). Combined statistical areas are combinations of metropolitan areas have a somewhat weaker economic connection, as defined by commuting patterns than within metropolitan areas (Note 1).

As in the San Francisco Bay Area, more Portlanders are now commuting from outside the metropolitan area in large enough numbers that four additional, metropolitan areas are now included in the Portland CSA.

Driving to Qualify from Corvallis and Albany

Perhaps most notable addition is Corvallis, seat of Benton County and home of Oregon State University. Corvallis is rather exurban to Portland, even though it is now officially in Portland’s commuting belt. At least 15 percent of resident workers in Benton County travel to one of the central counties of the Portland metropolitan area (Clackamas, Multnomah and Washington in Oregon and Clark in Washington) or vice versa. This is no 30 minute commute. Corvallis is 85 miles from downtown Portland. It is 65 miles from the nearest potential Portland MSA employment in southern Clackamas County. Further, the Corvallis metropolitan area is not adjacent to the Portland metropolitan area. To get to the Portland metropolitan area by the most direct route, a Benton County commuter passes through two other metropolitan areas Albany and Salem.

This would be a very long commute, even by comparison to the nation’s largest metropolitan regions. Take New York, for example. The New York CSA extends from outside of New Haven, Connecticut, to beyond Allentown, Pennsylvania, to beyond Toms River, New Jersey and includes all of Long Island. Yet some of the farthest reaches of New York are no closer to Manhattan than Corvallis to Portland. These include Bethlehem, Pennsylvania, New Haven, Connecticut, and Port Jervis, New York. Philadelphia, beyond the New York CSA, is only slightly farther away (90 miles).

Or, consider Los Angeles, which its undeserved reputation for sprawl. The Los Angeles CSA is the second largest in the nation. Yet, Banning, which sits on the mountain pass leading to Palm Springs is 85 miles from Los Angeles. San Clemente, the southernmost point in the CSA is only 60 miles from downtown. The expansive Portland commuter shed suggests that, in some ways, Portland, already far less dense, is also more sprawling.

Expansions for Linn, Marion, Polk and Cowlitz Counties

The Portland CSA added two more metropolitan areas in the Willamette Valley. Albany (Linn County), only about 15 miles closer than Corvallis is one. Salem, the state capital, was also added. Salem includes Marion and Polk counties and is 45 miles from Portland. To the north, Longview, Washington (Cowlitz County) was also added. By comparison with Corvallis, Longview seems close, at less than 50 miles from Portland.

The Portland CSA now stretches 175 miles from the southern Linn County border to the northern Cowlitz County border. There it has collided with the southerly expanding Seattle CSA, which now includes Lewis County (Centralia-Chehalis), 85 miles from downtown Seattle.

However, this does not imply 175 miles of continuous urbanization. Like all metropolitan areas, combined statistical areas, including Portland, have far more rural land than urban land.

Dispersing in the Metropolitan Area

Perhaps the greatest irony is that an “urban containment” policy designed to prevent sprawl could well be accelerating it. Higher prices, in part due to this policy, have forced more people to look ever further for housing that is affordable.

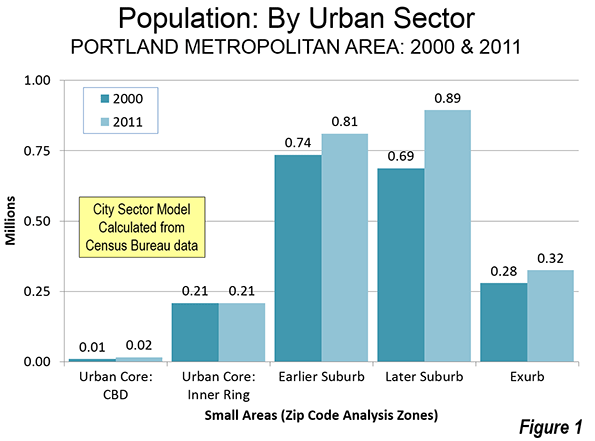

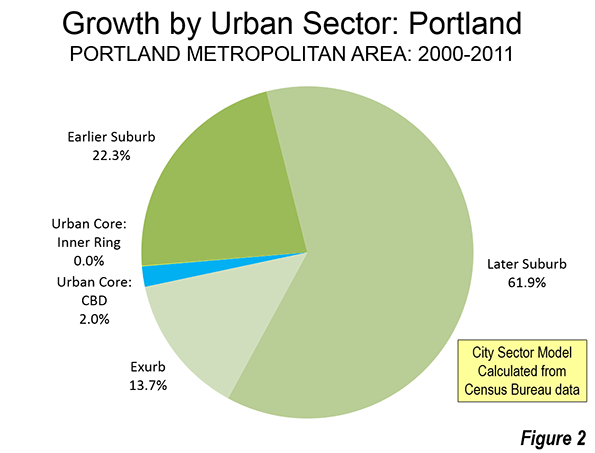

Approximately 98 percent of Portland’s population growth between 2000 and 2011 occurred in the suburbs (Note). There was a small, but significant percentage growth around the central business district, but its addition of fewer than 7,000 residents paled by comparison to the more than 325,000 added to the suburbs and exurbs. The balance of the urban core, (the inner ring) grew by little more than 100, which is glacial for an urban sector with more than 200,000 residents (less than 0.1 percent).

None of this should be surprising. The attractive inner city developments, especially the Pearl District, do not provide for the economic needs or wants of most people, as the population trend data indicates. Few households are drawn to buy less than one-half the space they want at nearly three times the price per square foot they would pay in outer suburbs like Forest Grove, Wilsonville or Hazel Dell.

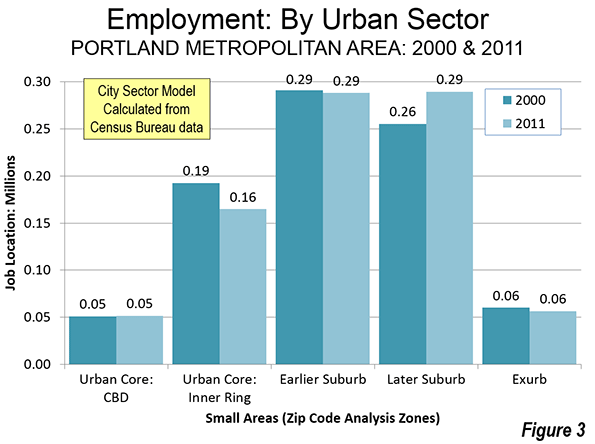

Job Dispersion

Fortunately for both the suburbanites and an exurbanites, Portland’s job market also dispersed between 2000 and 2011, meaning that a smaller percentage of commuting was to downtown or the balance of the urban core (Figure 3). That makes it easier to drive to qualify. It turns out that while planners plan, people usually make choices that suit their basic needs rather than those of a particular urban ideology.

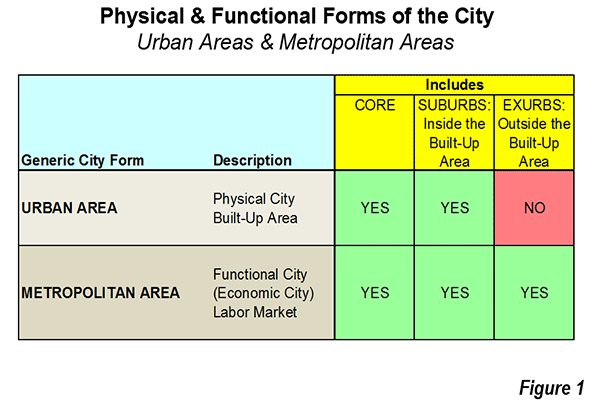

Note 1: Metropolitan areas are defined by commuting patterns. Oversimplifying, metropolitan areas are organized around central counties that contain all or part of large urban areas ("built-up" urban areas). All such counties are included in the metropolitan area as well as any counties that have a strong commuting interchange with the central counties. For example, in the case of Portland, the central counties are Multnomah, Washington and Clackamas in Oregon and Clark in Washington. Columbia and Yamhill in Oregon are outlying counties as well as Skamania in Washington. Combined statistical areas are created from combinations of metropolitan areas that meet a weaker commuting interchange threshold. A complete description of the commuting thresholds that apply to metropolitan areas and combined statistical areas is found here.

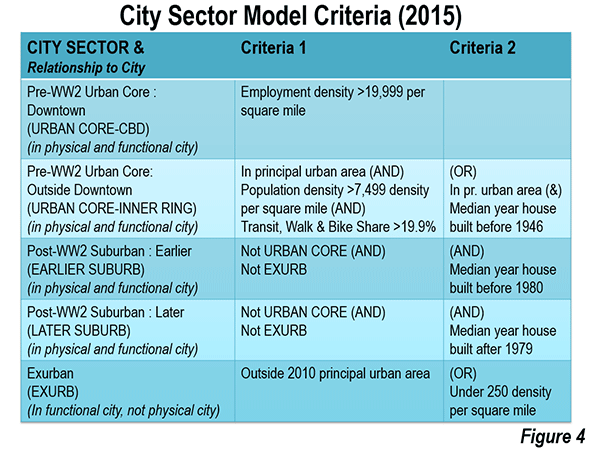

Note 2: Based on the City Sector Model (Figure 4), which classifies small areas (ZIP codes, more formally, ZIP Code Tabulation Areas, or ZCTAs) in metropolitan area in the nation based upon their behavioral functions as urban cores, suburbs or exurbs. The criteria used are generally employment and population densities and the extent of transit, versus car use. The purpose of the urban core sectors is to replicate, to the best extent possible, the urban form as it existed before World War II, when urban densities were much higher and when a far larger percentage of urban travel was on transit. The suburban and exurban sectors replicate automobile oriented suburbanization that began in the 1920s and escalated strongly following World War II. The data from 2000 is from the 2000 census. The 2011 data is from the 2009-2013 American Community Survey (mid-year 2011).

Photo: Benton County Courthouse, Corvallis (in the Portland commuter shed) by Gregkeene (Own work) [CC BY 3.0 us or CC BY-SA 3.0], via Wikimedia Commons

Wendell Cox is principal of Demographia, an international public policy and demographics firm. He is co-author of the "Demographia International Housing Affordability Survey" and author of "Demographia World Urban Areas" and "War on the Dream: How Anti-Sprawl Policy Threatens the Quality of Life." He was appointed to three terms on the Los Angeles County Transportation Commission, where he served with the leading city and county leadership as the only non-elected member. He served as a visiting professor at the Conservatoire National des Arts et Metiers, a national university in Paris. Wendell Cox is Chair, Housing Affordability and Municipal Policy for the Frontier Centre for Public Policy (Canada), is a Senior Fellow of the Center for Opportunity Urbanism and is a member of the Board of Advisors of the Center for Demographics and Policy at Chapman University.

David S. Holloway/Getty

David S. Holloway/Getty