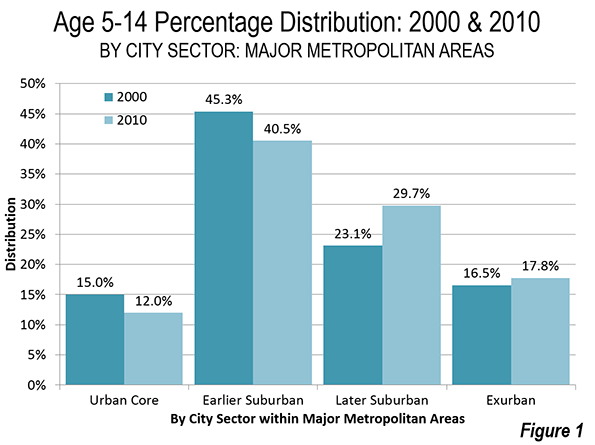

The urban cores of the nation’s 52 major metropolitan areas (over 1 million population) lost nearly one-fifth of their school age population between 2000 and 2010. This is according an analysis of small area age group data for children aged 5 to 14 from Census Bureau data, using the City Sector Model. Over the period, the share of 5 to 14 age residents living in the functional urban cores declined from 15.0 percent to 12.0 percent (Figure 1).

The City Sector Model

The City Sector Model analysis avoids the exaggeration of urban core data that necessarily occurs from reliance on the municipal boundaries of core cities (which are themselves nearly 60 percent suburban or exurban, ranging from as little as three percent to virtually 100 percent). It also avoids the use of the newer "principal cities" designation of larger employment centers within metropolitan areas, nearly all of which are suburbs, but are inappropriately joined with core municipalities in some analyses. The City Sector Model" small area analysis method is described in greater detail in Note 1 below (previous articles are listed in Note 2). The approach is similar to the groundbreaking work of David Gordon, et al at Queen’s University for Canadian metropolitan areas.

School Age Losses

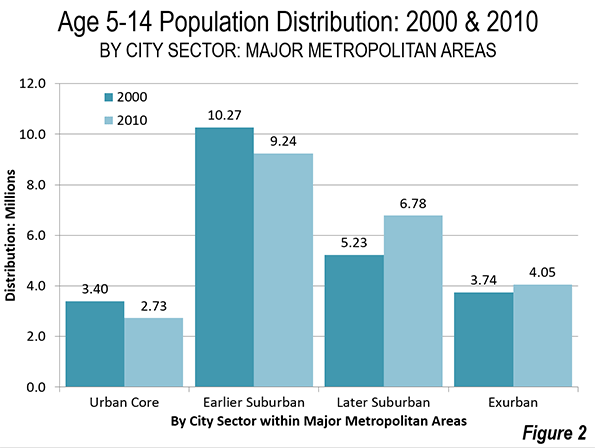

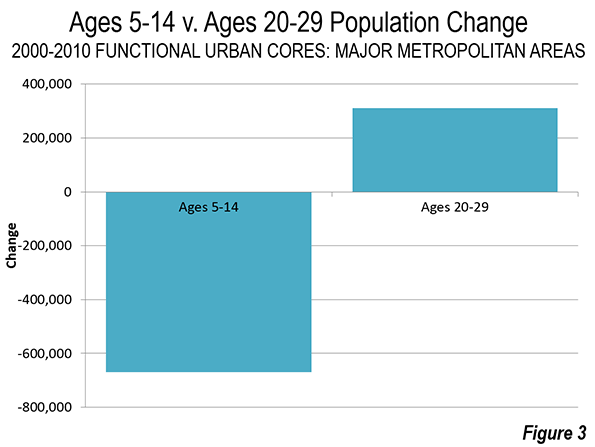

The urban core school-age population dropped from approximately 3.40 million in 2000 to 2.73 million in 2010, for a loss of 670,000 (Figure 2). Much has been made about the affinity of the Millennial generation for the urban cores. Despite this, our small area analysis indicated that the percentage of 20 to 29 year olds living in the functional urban cores declined between 2000 and 2010, with 88 percent of the growth in suburbs and exurbs (see Dispersing Millennials). Coincidentally, over the period, there was a reduction of two school age children in the urban cores for every additional resident aged 20 to 29 (Figure 3).

A loss was also sustained in the earlier suburbs (with median house construction dates between 1946 and 1979). The school-age population declined slightly more than 1 million in the earlier suburban areas. In 2000, 45.3 percent of school age children lived in the earlier suburbs, a figure that declined to 40.5 percent in 2010.

Virtually all of the gain in 5 to 14 age residents was in the later suburban areas (a median house construction dates of 1980 or later) and exurban areas. Overall, these two city sectors added 1.9 million school-age children, while the urban cores and the earlier suburban areas experienced a reduction of 1.7 million, for a reduction of approximately 10 percent.

The largest increase was in the newer suburban areas (median house construction dates of 1980 or later), where 1.47 more school-age children lived in 2010 than in 2000. This represented an increase of approximately 30 percent. Exurban areas have a more modest increase of 310,000 school-age children, up 8.3 percent from 2000.

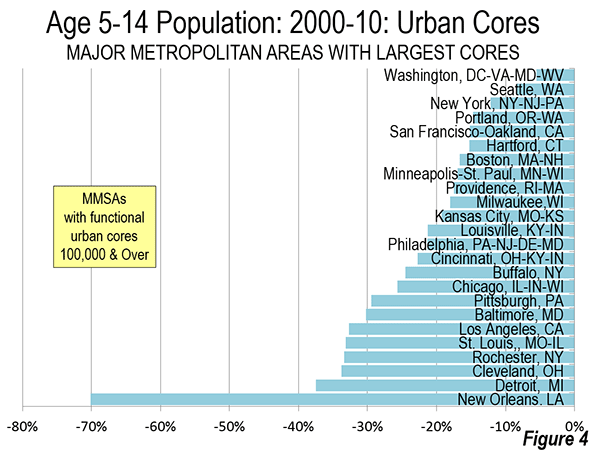

Losses in the Largest Urban Cores

All of the large urban cores in the metropolitan areas experienced losses in school aged children from 2000 to 2010. Among the 24 urban cores with more than 100,000 residents, Washington (-5.5 percent) and Seattle (-8.4 percent) came the closest to retaining their 2000 school age numbers in 2010. Seven large urban cores experienced losses of at least 30 percent. Baltimore’s loss was approximately 30 percent. Los Angeles joined rust belt cities St. Louis, Rochester and Cleveland at 33 percent to 34 percent and Detroit at 38 percent. New Orleans had the largest loss (-70.2 percent), owing in part to population loss from the disastrous hurricanes (Figure 4).

Finally, in all of the 52 metropolitan areas, the later suburban and exurban areas (combined) retained more of their school age children than the urban cores and earlier suburbs. There were gains in 45 of the later suburban and exurban areas.

Better Schools: The Necessary (But Maybe Not Sufficient) Condition

One of the issues of most interest among urban analysts has been whether urban cores will be able to retain the share of Millennials that they have attracted. The functional urban cores seem likely to maintain their attraction for younger adults, so long as the cores sustain their improved living environment (such as much lower crime rates than before and continued investment by retailers and other commercial business to support the new populations).

However, the continuing exodus of people with school-age children described seems to indicate that young adults tend to move to the suburbs and exurbs around the time their children enroll in school. Suburban and exurban schools often provide better educations than urban core schools. The Editorial Projects in Education found that high school graduation rates were 77.3 percent in suburban school districts, compared to 59.3 percent in "urban" school districts (Note 3). There are other difficulties as well, such as having sufficient defensible outdoor space for children to play and for parents to feel secure. But education seems likely to be the most important consideration.

Of course, in urban areas the highly affluent can enroll their children in private schools. The alternative of private schools can be overly expensive, inducing households to relocate to school districts with higher quality education. According to research by Chief Economist Jed Kolko of Trulia: “Private school enrollment in the lowest-rated school districts is more than four times as high as private school enrollment in the highest-rated school districts after adjusting for neighborhood demographic differences."

A balanced broad age distribution of households, including those with children of school age, is not likely to be achieved in urban cores unless Millennials are retained in substantial numbers. Once having moved, the chances of their returning are slim, because households move less frequently as they move up the age scale.

Note 1: The City Sector Model allows a more representative functional analysis of urban core, suburban and exurban areas, by the use of smaller areas, rather than municipal boundaries. The more than 30,000 zip code tabulation areas (ZCTA) of major metropolitan areas and the rest of the nation are categorized by functional characteristics, including urban form, density and travel behavior. There are four functional classifications, the urban core, earlier suburban areas, later suburban areas and exurban areas. The urban cores have higher densities, older housing and substantially greater reliance on transit, similar to the urban cores that preceded the great automobile oriented suburbanization that followed World War II. Exurban areas are beyond the built up urban areas. The suburban areas constitute the balance of the major metropolitan areas. Earlier suburbs include areas with a median house construction date before 1980. Later suburban areas have later median house construction dates.

Urban cores are defined as areas (ZCTAs) that have high population densities (7,500 or more per square mile or 2,900 per square kilometer or more) and high transit, walking and cycling work trip market shares (20 percent or more). Urban cores also include non-exurban sectors with median house construction dates of 1945 or before. All of these areas are defined at the zip code tabulation area (ZCTA) level.

Note 2: The City Sector Model articles are:

From Jurisdictional to Functional Analyses of Urban Cores & Suburbs

The Long Term: Metro American Goes from 82 percent to 86 percent Suburban Since 1990

Beyond Polycentricity: 2000s Job Growth (Continues to) Follow Population

Urban Cores, Core Cities and Principal Cities

Large Urban Cores: Products of History

New York, Legacy Cities Dominate Transit Urban Core Gains

Boomers: Moving Farther Out and Away

Seniors Dispersing Away from Urban Cores

Metropolitan Housing: More Space, Large Lots

City Sector Model Small Area Criteria

Note 3: This report (which was prepared with support from the America’s Promise Alliance and the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation) provides graduation rates using the US Department of Education "local codes." This typology generally defines "urban" school districts as those in core cities as well as other principal cities (such as Arlington, Texas and Mesa, Arizona). Most of the population of core cities and principal cities is classified as functionally suburban (see: Urban Cores, Core Cities and Principal Cities). Further, the typology classifies some districts as suburban that have large urban components (such as Las Vegas, Miami, Louisville and Honolulu), which is necessary because of county level school districts that include both urban cores and suburban areas. As a result the functionally suburban component of urban districts is overstated and the functionally suburban component of suburban districts is understated. Because urban graduation rates tend to be less than suburban rates, both of these factors seem likely to overstate the "urban" graduation rates and understate the "suburban" graduation rates.

Wendell Cox is principal of Demographia, an international public policy and demographics firm. He is co-author of the "Demographia International Housing Affordability Survey" and author of "Demographia World Urban Areas" and "War on the Dream: How Anti-Sprawl Policy Threatens the Quality of Life." He was appointed to three terms on the Los Angeles County Transportation Commission, where he served with the leading city and county leadership as the only non-elected member. He was appointed to the Amtrak Reform Council to fill the unexpired term of Governor Christine Todd Whitman and has served as a visiting professor at the Conservatoire National des Arts et Metiers, a national university in Paris.

Photo: School buses in suburban Atlanta (by author)