Desperate times call for desperate measures. The Rust Belt, a region familiar to the air of anxiety, knows this all too well, particularly the “desperate measures” part.

A case in point: During the 1990’s, Pittsburgh, like many of its Rust Belt peers, was in the midst of a fit of brain drain hysteria. Strategic policy was needed. So the powers that be thought of a marketing campaign meant to saturate the minds of the educated “young and the restless” who were thinking about exiting the Steel City. Pittsburgh demographer and economist Chris Briem, in a 2000 op-ed in the Post-Gazette, picks it up from here:

“The focus on retaining vs. attracting workers is pervasive in local policies. One marketing character thought of by the Pittsburgh Regional Alliance, whose mission is to promote Pittsburgh, was the genial "Border Guard Bob." The image was of an older, uniformed sentinel on Pittsburgh’s borders keeping our citizens, in particular the younger workers, from leaving the region. This is the same logic that inspired the East Germans to build a wall around Berlin and is likely to have as much success in the long-run.”

Luckily for Pittsburgh, Border Guard Bob never materialized. Policy-wise, building walls is terrible form in the age of information. Still, the aura of desperation remained in the region, despite its illogicality. For instance, in his 2002 piece called “Young people are not leaving Pittsburgh”, Briem crunched the numbers to find the region’s brain drain wasn’t. Yet he found it hard “to convince Pittsburghers that the outmigration of youth is not the problem it once was,” blaming “a persistence of memory” stemming from the regional exodus in the 1980’s.

As a demographer and economic thinker in Cleveland, I can sympathize with Briem. Cleveland, too, is prone to bouts of brain drain hysteria. A recent report highlighted in the New York Times called “The Young and Restless and the Nation’s Cities” was enough set off a flare-up. The report found that between 2000 and 2012, Greater Cleveland added less than 800 25- to 34-year-olds with a college degree—an increase of 1%. The metro ranked second last out of 51 metros, behind only Detroit.

Obviously, those numbers are not good. That said, from a methodological standpoint, the study has its limitations. Specifically, the analysis cuts through four economic eras: 2000, the end of a prolonged expansionary period; 2005 to 2007, the middle of a jobless economic recovery; 2008 to 2010, the throes of a deep global recession; and 2011 to 2012, a period of economic recovery.

Why does this matter? Migration patterns are affected by quite different economic circumstances nationally. This is especially true for the 25- to 34-year-old cohort, who are the most mobile, if not fickle, group.

For example, Greater Cleveland’s lack of a young adult brain gain from 2000 to 2012 resulted from a substantial decrease of nearly 16,000 25- to 34-year-olds with a 4-year college degree from 2000 to 2006. The 2001 recession and subsequent jobless recovery hit Cleveland hard. However, my research at the Center for Population Dynamics at Cleveland State University showed that Greater Cleveland recouped the losses from earlier in the decade, gaining approximately 17,000 25- to 34-year-olds with a 4-year degree from 2006 to 2012—an increase of 23%.

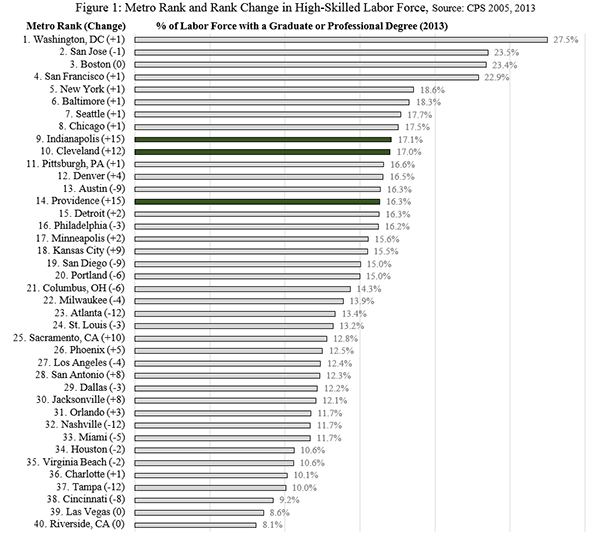

Moreover, the Census recently released data for 2013, which allows a comparison of the nation’s top big-city metros for 2011 to 2013: the current era of economic recovery. Put simply, what large metros have the momentum? Has there been a shift in where the “young and the restless” are attempting to settle down?

The results are surprising. Cleveland ranks 3rd in the nation, with a 19.85% increase in the number of young adults with a college degree, behind the Sun Belt metros Nashville and Orlando. And no, this percentage “pop” for the region is not simply due to the fact that Cleveland had a really small base of young college graduates. In fact, the region’s 3-year gain of 15,557 ranks Cleveland 15th in total gains, despite being the 29th largest metro in the nation. To put this in perspective, Greater Cleveland had a larger total growth than Chicago, and nearly seven times the gain of Portland: the nation’s poster child for where the “young and restless” go to “live, work, play”.

| Table 1: 25-to-34-year-olds with at least a Bachelor’s degree, Change, 2011 to 2013 | ||||

| Metro Area | 2011 | 2013 | % Change 2011 to 2013 | Total Change 2011 to 2013 |

| Nashville-Davidson–Murfreesboro–Franklin, TN | 82,588 | 103,239 | 25.01% | 20,652 |

| Orlando-Kissimmee-Sanford, FL | 83,706 | 101,066 | 20.74% | 17,361 |

| Cleveland-Elyria, OH | 78,392 | 93,949 | 19.85% | 15,557 |

| Riverside-San Bernardino-Ontario, CA | 97,804 | 116,767 | 19.39% | 18,963 |

| Jacksonville, FL | 47,792 | 56,256 | 17.71% | 8,464 |

| Austin-Round Rock, TX | 119,482 | 138,240 | 15.70% | 18,758 |

| Seattle-Tacoma-Bellevue, WA | 208,647 | 240,267 | 15.15% | 31,620 |

| Sacramento–Roseville–Arden-Arcade, CA | 77,075 | 87,435 | 13.44% | 10,360 |

| Salt Lake City, UT | 55,036 | 62,124 | 12.88% | 7,088 |

| Pittsburgh, PA | 117,402 | 131,770 | 12.24% | 14,368 |

| Philadelphia-Camden-Wilmington, PA-NJ-DE-MD | 306,271 | 341,220 | 11.41% | 34,948 |

| Columbus, OH | 106,144 | 118,224 | 11.38% | 12,080 |

| Houston-The Woodlands-Sugar Land, TX | 266,289 | 295,230 | 10.87% | 28,941 |

| Buffalo-Cheektowaga-Niagara Falls, NY | 52,231 | 57,727 | 10.52% | 5,496 |

| Dallas-Fort Worth-Arlington, TX | 296,927 | 327,330 | 10.24% | 30,403 |

| New Orleans-Metairie, LA | 54,104 | 59,616 | 10.19% | 5,512 |

| San Jose-Sunnyvale-Santa Clara, CA | 135,306 | 148,978 | 10.10% | 13,672 |

| Detroit-Warren-Dearborn, MI | 154,542 | 170,122 | 10.08% | 15,580 |

| San Francisco-Oakland-Hayward, CA | 320,585 | 350,490 | 9.33% | 29,904 |

| Baltimore-Columbia-Towson, MD | 150,003 | 163,941 | 9.29% | 13,938 |

| New York-Newark-Jersey City, NY-NJ-PA | 1,216,127 | 1,327,778 | 9.18% | 111,651 |

| Los Angeles-Long Beach-Anaheim, CA | 631,960 | 688,057 | 8.88% | 56,098 |

| St. Louis, MO-IL | 134,267 | 145,978 | 8.72% | 11,710 |

| Oklahoma City, OK | 58,027 | 63,084 | 8.71% | 5,057 |

| San Antonio-New Braunfels, TX | 85,240 | 92,524 | 8.55% | 7,284 |

| Hartford-West Hartford-East Hartford, CT | 59,780 | 64,784 | 8.37% | 5,004 |

| Denver-Aurora-Lakewood, CO | 163,026 | 176,237 | 8.10% | 13,211 |

| Milwaukee-Waukesha-West Allis, WI | 79,404 | 85,793 | 8.05% | 6,390 |

| Louisville/Jefferson County, KY-IN | 50,790 | 54,849 | 7.99% | 4,060 |

| Virginia Beach-Norfolk-Newport News, VA-NC | 67,664 | 72,888 | 7.72% | 5,224 |

| Tampa-St. Petersburg-Clearwater, FL | 99,316 | 106,504 | 7.24% | 7,187 |

| San Diego-Carlsbad, CA | 167,735 | 179,850 | 7.22% | 12,114 |

| Birmingham-Hoover, AL | 47,340 | 50,675 | 7.04% | 3,335 |

| Kansas City, MO-KS | 102,284 | 109,455 | 7.01% | 7,171 |

| Rochester, NY | 48,844 | 52,212 | 6.90% | 3,368 |

| Boston-Cambridge-Newton, MA-NH | 348,490 | 371,303 | 6.55% | 22,813 |

| Phoenix-Mesa-Scottsdale, AZ | 163,995 | 174,694 | 6.52% | 10,699 |

| Providence-Warwick, RI-MA | 64,205 | 68,349 | 6.45% | 4,144 |

| Raleigh, NC | 76,164 | 80,447 | 5.62% | 4,283 |

| Indianapolis-Carmel-Anderson, IN | 91,083 | 95,827 | 5.21% | 4,744 |

| Las Vegas-Henderson-Paradise, NV | 59,998 | 63,058 | 5.10% | 3,060 |

| Cincinnati, OH-KY-IN | 95,084 | 99,225 | 4.36% | 4,142 |

| Minneapolis-St. Paul-Bloomington, MN-WI | 214,755 | 223,640 | 4.14% | 8,885 |

| Washington-Arlington-Alexandria, DC-VA-MD-WV | 460,693 | 477,706 | 3.69% | 17,013 |

| Chicago-Naperville-Elgin, IL-IN-WI | 558,464 | 572,324 | 2.48% | 13,860 |

| Atlanta-Sandy Springs-Roswell, GA | 272,907 | 279,232 | 2.32% | 6,325 |

| Portland-Vancouver-Hillsboro, OR-WA | 119,490 | 121,794 | 1.93% | 2,304 |

| Miami-Fort Lauderdale-West Palm Beach, FL | 221,294 | 224,388 | 1.40% | 3,094 |

| Richmond, VA | 59,907 | 59,289 | -1.03% | -618 |

| Memphis, TN-MS-AR | 52,911 | 49,412 | -6.61% | -3,499 |

| Source: ACS 1-Year, 2011, 2013 Note: Charlotte was removed from the analysis due to substantial geographic changes in the MSA designation from 2011 to 2013. Created by the Center for Population Dynamics at Cleveland State Univeristy, October, 2014. | ||||

What gives?

Part of the answer may be economic. For example, my colleagues Joel Kotkin and Aaron Renn recently analyzed the growth in per capita GDP from 2010 to 2013 for Forbes in a piece entitled “The cities that are benefiting the most from the economic recovery”. Cleveland ranked 15th in the nation, with a 6% increase. In terms of income, the metro is 5th in the nation in the total per capita income increase from 2010 to 2012, behind Houston, San Jose, Oklahoma, and San Francisco.

In understanding Cleveland’s nascent young adult brain gain, the broader economic performance is important. Healthier economies make metros “stickier” for those here and more of a magnet for those who aren’t. And while there also is the element of “Rust Belt Chic”, or the lure of so-called “authentic” places that counter the “Brooklynization” of American cities, Cleveland as a destination, or a “consumer city”, will always take a back seat to Cleveland as a “producer city”, which is a metro of good jobs, good schools, and affordable housing. The producer city focuses on the creation of value, not simply the consumption of things. This is not to say amenities, such as a good culinary and microbrew scene, are not important, it only says that if the talent you attract has nothing to produce or nowhere to live, well, all play and no work makes Jack a dull boy.

Talent attraction, then, is only part of the formula in Cleveland’s ongoing and difficult economic restructuring. Talent production is also needed, for both natives and newcomers, regardless of the age group. But emphasizing the latter entails knowing the score on the former. Brain drain hysteria breeds desperation.

And desperate times call for desperate measures—and bad policy.

This piece first appeared at Crains Cleveland.

Richey Piiparinen is a Clevelander, writer, and Senior Research Associate heading the Center for Population Dynamics at Cleveland State University.