With the growing bifurcation of incomes in America, most regions would prefer, if given a choice, to attract higher-earning professionals to their areas. These people generate more spending in the community and contribute more taxes to the till.

So, what does it take to get them there?

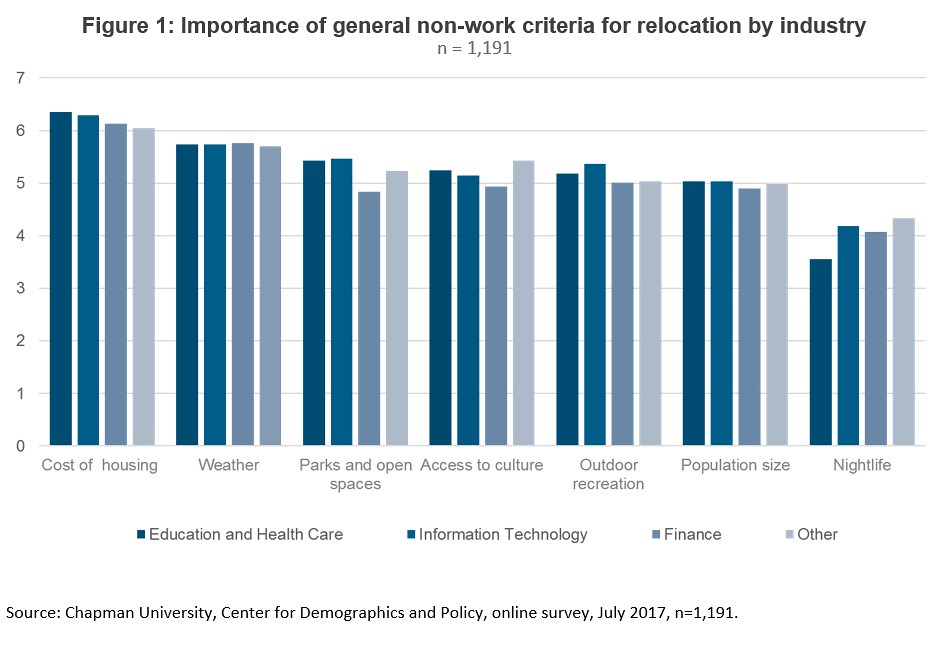

The Center for Demographics and Policy at Chapman University just completed a national survey, fielded and tabulated by The Cicero Group, of 1,191 professionals: people aged 25-64 with household incomes greater than $80,000, and who work in education, healthcare, information technology, finance or other professional services jobs. We asked respondents to rate which general non-work factors, which educational and social non-work factors, and which work-related factors were most important to them in determining where they would want to move, assuming an attractive job opportunity presented itself. While there were some differences between different industries, the variances were relative small, in most cases.

Overall, the results surprised us by how young and middle aged professionals —who are almost uniformly said to prefer living in an edgy, dense urban environment— actually opt for far more traditional, or even banal, alternatives. Professionals are more focused on family lifestyle issues as they consider where they would want to live. While they do not want to live in a cultural wasteland, they prioritize outdoor activities, a lack of crowding and an affordable house over exciting nightlife.

These preferences are reflected in the real life choices professionals made. Research by Chapman’s Erika Orejola, using 2015 ESRI data, shows that 25 of the top 30 counties with the highest concentrations of individuals earning $75,000 or more are largely or entirely suburban.

To understand the professional class’ actual choices —- as opposed to common media stereotypes — the survey is very useful. Figure 1 below summarizes general non-work factors. Housing costs were clearly the most important factor they considered. Weather was second. Parks and open spaces, access to culture, outdoor recreation and population size were clustered together as the next most important variables. People employed in the education and healthcare fields did not consider an area’s nightlife to be as important a criterion for relocation as those in other professions.

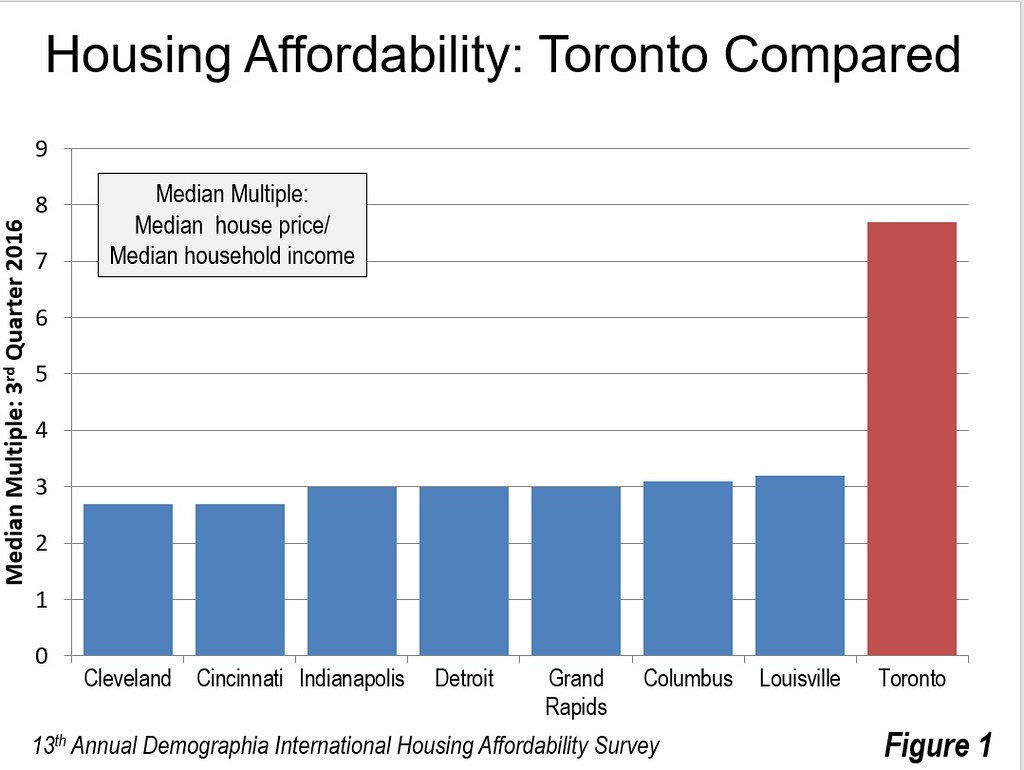

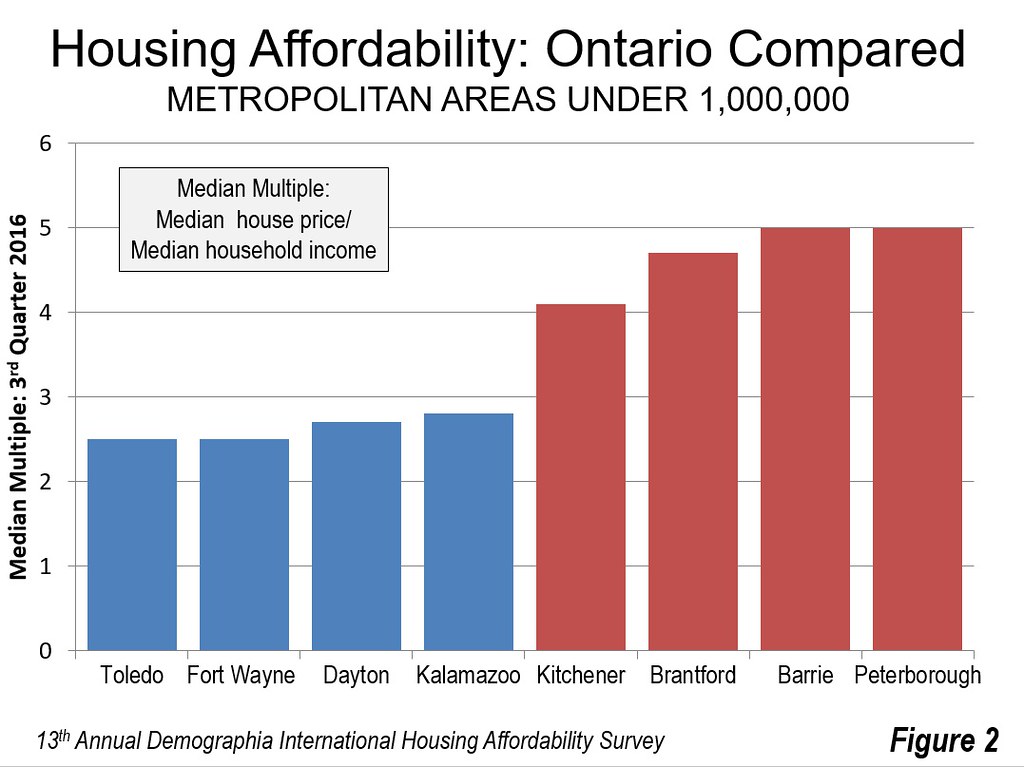

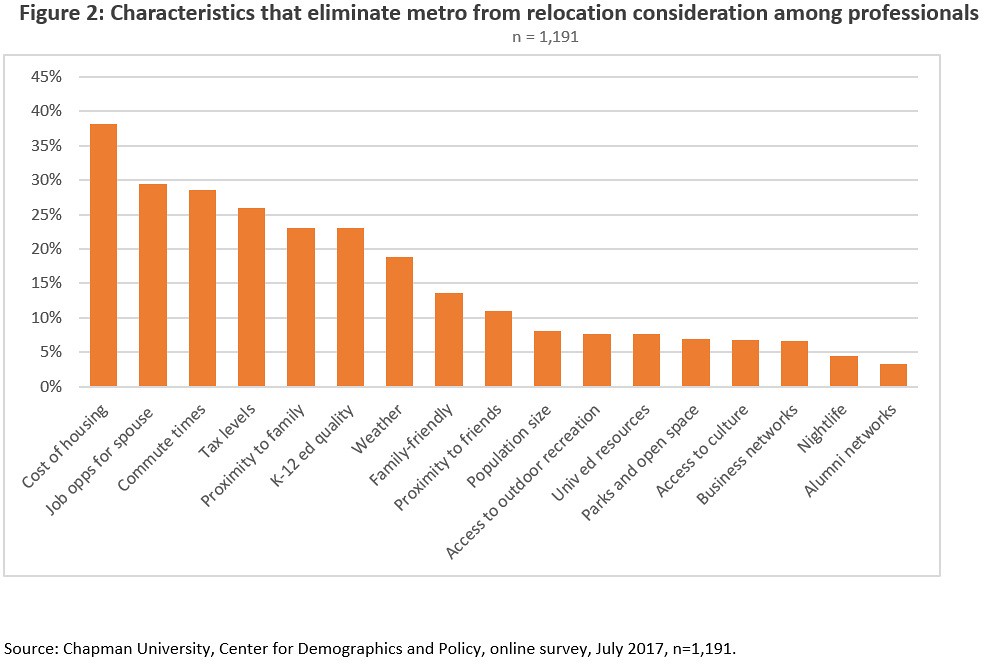

Housing costs, in addition to being an important factor in why professionals move into an area, are also a reason someone removes an area from consideration, as you can see in Figure 2. 37% of professionals say they would eliminate an area from consideration because of its high housing costs.

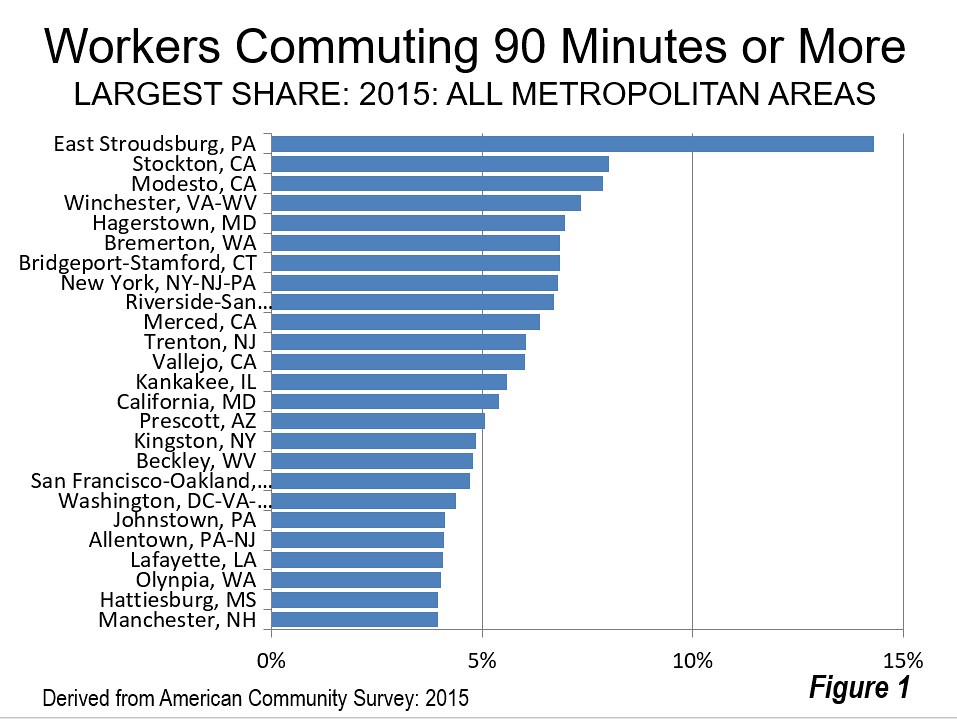

Professionals often live in two income households. That may explain why lack of “job opportunities for my spouse” was the second most prevalent reason for why people would eliminate an area from consideration. It was cited about as frequently as “commute times” by respondents.

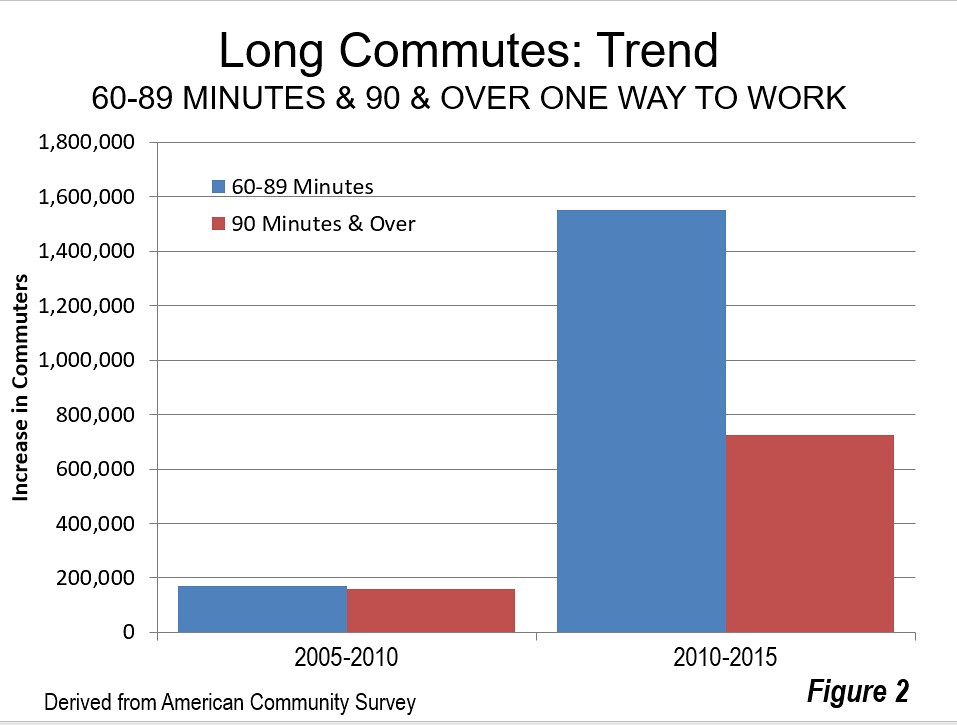

Looking at other general, non-work variables from Figure 1, we see clearly that many professionals are looking for a more balanced lifestyle in the place they live. People want an area to be of sufficient size to offer interesting cultural alternatives, nightlife and restaurant options. However, they shy away from crowding, places with major traffic problems, and long commute times (which is also addressed in Figure 4.) And they want to be able to relax in what they see as a non-frenetic area with outdoor recreation, parks and open spaces.

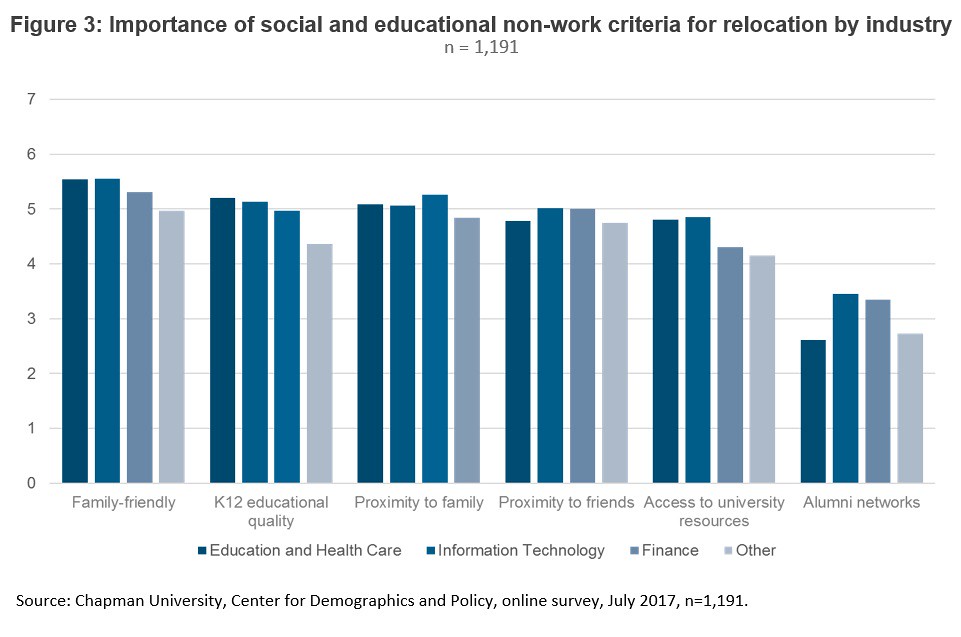

Professionals we surveyed are clearly family-oriented. As we see in Figure 2, their rating of “family-friendliness”, proximity to family and friends and their kid’s K-12 educational quality ranks top in importance. Access to university resources were deemed to be important, however, access to a professional’s alumni networks was not as much of a priority, something of a surprise. When looked at from the perspective of eliminating a region for consideration, proximity to family was a very important variable, while proximity to friends was much less of a “deal killer”.

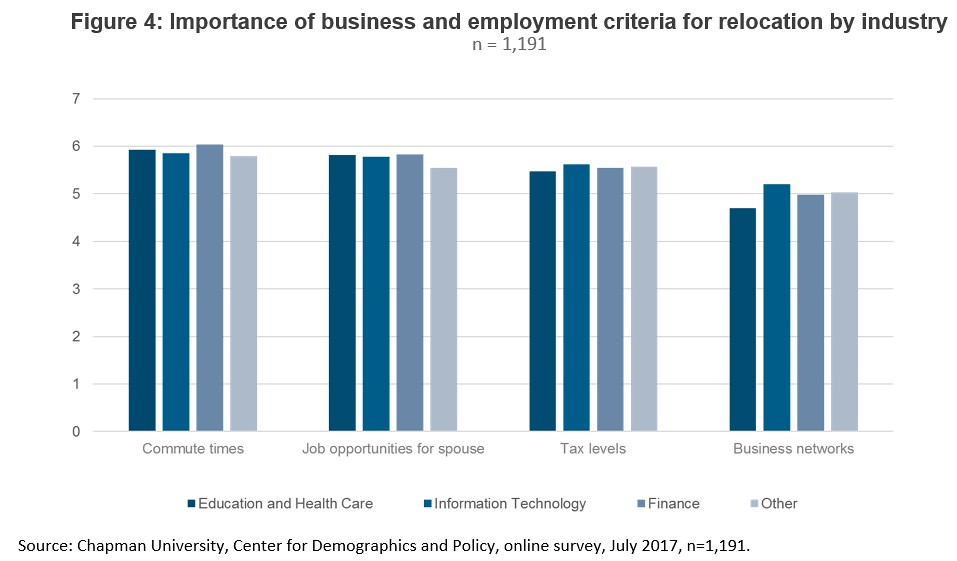

Looking at work-related criteria in Figure 4, we see that commute time and job opportunities for spouses rank as highly important. As with housing costs, these two criteria are both important in deciding to relocate to an area and a “deal killer” if they are not there. Tax levels are also of high importance to professionals. Given their higher incomes that seems logical. Having strong business networks is almost as important as tax levels, and is of greater concern to people in IT, finance and other professional services areas than it is to education and healthcare professionals.

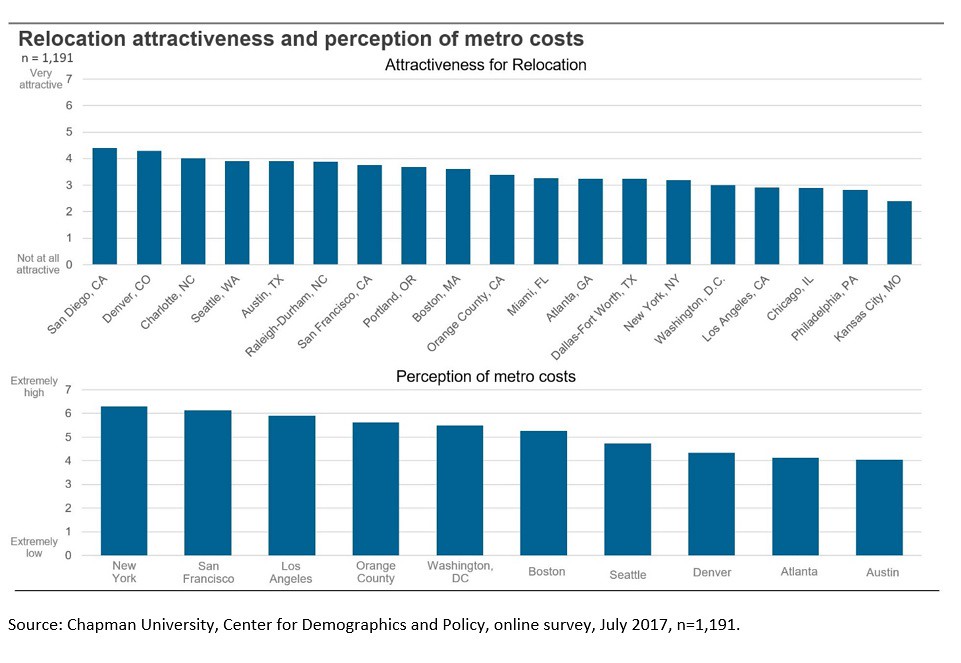

So, given all of these criteria and deal killers, how do the different metro areas stack up against each other as a magnet for professional talent? We gave professionals a choice of 25 metro areas to choose from. These areas were selected by looking at the census data changes in the past decade and seeing where the highest concentrations of professional jobs were located.

Looking at Figure 5, we see that professionals view San Diego as the most attractive metro in the country. That may seem counter-intuitive, given the high actual cost of real estate in Southern California and the high tax levels in California in general. However, professionals do not appear to perceive San Diego as being among the top 10 highest cost places to live. That distinction falls to New York, followed closely by San Francisco.

Denver, Charlotte, Seattle, Austin and Raleigh are next in line in terms of perceived attractiveness overall. Orange County, CA ranks much higher in attractiveness than its northern neighbor, Los Angeles. It is perceived to have the 4th highest cost of living in the country, among places that attract professionals.

Of significance is the fact that no region actually stands out as the “beauty contest winner” of regions. The highest scoring metro, San Diego, received a 4.3 out of 7 score in attractiveness, indicating that there is no “perfect” in the minds of professionals. To them, there are certain factors that are “must haves”, such as affordable housing, jobs for spouses and reasonable commute times. Rather than obsess over trendy hipsterism, regions seeking to lure professionals need, more than anything, to focus on the basics that shape family quality of life.

Marshall Toplansky is Clinical Assistant Professor of Management Science at Chapman University. He is co-principal investigator, with Joel Kotkin on “The Orange County Model”, a demographic and econometric research project to identify growth strategies for that region. He is formerly Managing Director of KPMG’s national center of excellence in data and analytics, and is co-founder of Wise Window, a pioneer in sentiment analysis and the use of big data for predictive models. He lives in Orange, California.