An Excerpt from Joel Kotkin’s Forthcoming book The New Class Conflict available for pre-order now from Telos Press and in bookstores September, 2014.

In ways not seen since the Gilded Age of the late nineteenth century, America is becoming a nation of increasingly sharply divided classes. Joel Kotkin’s The New Class Conflict breaks down these new divisions for the first time, focusing on the ascendency of two classes: the tech Oligarchy, based in Silicon Valley; and the Clerisy, which includes much of the nation’s policy, media, and academic elites.

The Proleterianization of the Middle Class

From early in its history, the United States rested on the notion of a large class of small proprietors and owners. “The small landholders,” Jefferson wrote to his fellow Virginian James Madison, “are the most precious part of a state.” To both Jefferson and Madison, both the widespread dispersion of property and limits on its concentration—“the possession of different degrees and kinds of property”—were necessary in a functioning republic.

Jefferson, admitting that the “equal division of property” was “impractical,” also believed “the consequences of this enormous inequality producing so much misery to the bulk of mankind” that “legislators cannot invent too many devices for subdividing property.” The notion of a dispersed base of ownership became the central principle which the Republic was, at least ostensibly, built around. As one delegate to the 1821 New York constitutional convention put it, property was “infinitely divided” and even laborers “expect soon to be freeholders” was a bulwark for the democratic order.

This notion of American opportunity has ebbed and flowed, but generally gained ground well into the 1960s and 1970s. The very fact that the United States was more demographically dynamic, notes Thomas Piketty, naturally reduced the role of inherited wealth compared to Europe, most notably in France, where population growth was slower. Mass prosperity hit a high point in America in the first decades after the Second World War, the period where the country achieved its highest share of world GDP at some forty percent. By the mid-1950s the percentage of households earning middle incomes doubled to 60 percent compared with the boom years of the 1920s. By 1962 over 60 percent of Americans owned their own homes; the increase in homeownership, notes Stephanie Coontz, between 1946 and 1956 was greater than that achieved in the preceding century and a half.

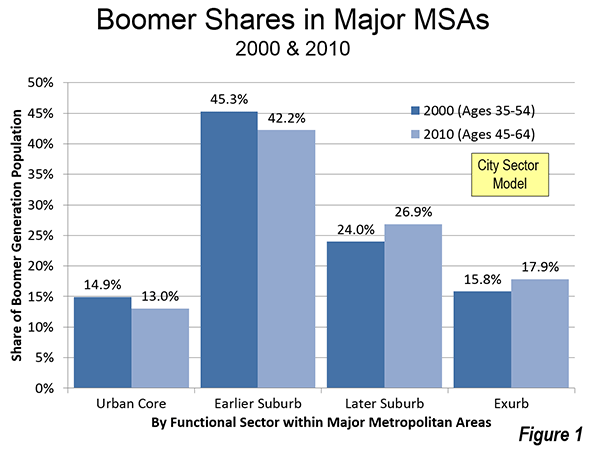

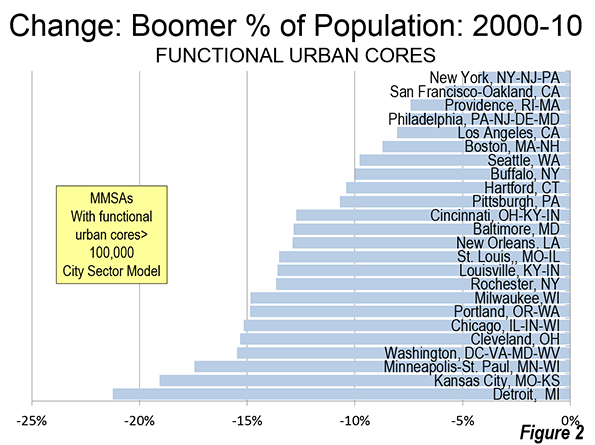

But today, after decades of expanding property ownership, the middle orders—what might be seen as the inheritors of Jefferson’s yeoman class—now appear in a secular retreat. Homeownership, which peaked in 2002 at nearly 70 percent, has dropped, according to the U.S. Census, to 65 percent in 2013, the lowest in almost two decade. Although some of this may be seen as a correction for the abuses of the housing bubble, rising costs, stagnant incomes and a drop off of younger first time buyers suggest that ownership may continue to fall in years ahead.

The weakness of the property owning yeomanry comes at a time when other classes, notably the oligarchs and the Clerisy, have gained power and influence. Over twenty years ago Christopher Lasch argued that “the new class” was arising that “begins and ends with the knowledge industry.” For this group, the rest of society, he suggested, exists only “as images and stereotypes.” Progressive theorists, such as Ruy Texerira, have suggested that, in the evolving class structure, the traditional middle and working class is of little importance compared to the rise of a mass “upper middle class” consisting largely of professionals, tech workers, academics, and high-end government bureaucrats.

The Economic Decline of the Yeomanry

All this suggests what could be seen as the proletarianization of the yeoman class. In the four decades since 1971 the percentage of those earning between two thirds and twice the national median income has shrunk, according to Pew, from over sixty to barely fifty percent of the population. While middle class incomes have fallen relative to the upper income groups, house prices and health insurance, utilities and college tuition costs have all soared.

This reflects some very dramatic changes in the nature of the employment market. For over a decade, job gains have been concentrated largely in the low-wage service sector, such as in retail or hospitality, which alone accounted for nearly sixty percent of job gains; in contrast middle income positions actually have been declining. Meanwhile, taxes on corporate profits, which are at an all time high, have fallen to near historic lows.

This trend has continued even in the recovery. Between 2010 and 2012, the middle sixty percent of households, did worse not only than the wealthy, but even the poorest quintile between 2010 and 2012. In the years of the recovery from the Great Recession the middle quintiles income dropped by 1.2 percent while those of the top five percent grew by over five percent. Overall the middle sixty percent have seen their share of the national pie fall from 53 percent in 1970 to barely 45 percent in 2012. Of roughly one in three people born into middle class households, those earning between the 30th and 70th percent of income now fall out of that status as adults.

This decline, not surprisingly, has engendered a dour mood among much of the yeomanry. For many, according to a 2013 Bloomberg poll, the American dream seems increasingly out of reach; this opinion was held by a margin of two to one among all Americans, and three to one among those making under $50,000, but also a majority earning over $100,000 annually. By margins of more than two to one, more Americans believed they enjoy fewer economic opportunities than their parents, and will experience far less job security and disposable income. This pessimism is particularly intense among white working class voters, and large sections of the middle class.

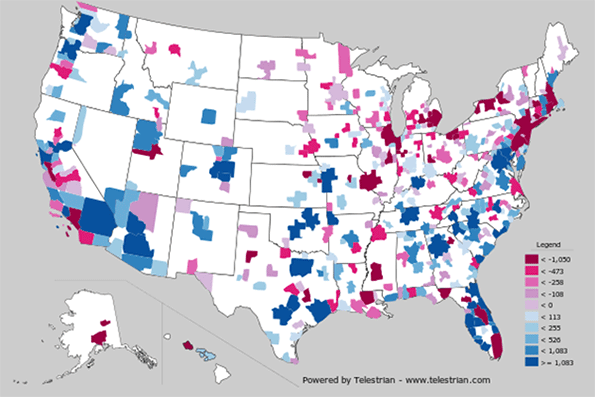

Many people who once had decent incomes, and may have owned or hoped to own a house or start a business have slipped to the lower rungs of the economy. In the past decade, the number of people working part-time and receiving such benefits as food stamps has expanded well beyond inner cities and impoverished rural hamlets. Many of the long-term unemployed are older, and often somewhat well-educated workers, who have fallen from the middle class over the past decade. The curse of poverty has also expanded more into suburban locations; something widely cited by the urban-centric Clerisy, but further confirms the yeomanry’s stark decline.

The Assault on Small Business

Perhaps nothing reflects the descent of the yeomanry than the fading role of the ten million small businesses with under 20 employees, which currently employ upwards of forty million Americans. Long a key source of new jobs, small business start-ups have declined as a portion of all business growth from 50 percent in the early 1980s to 35% in 2010. Indeed, a 2014 Brookings report, revealed that small business “dynamism”, measured by the growth of new firms compared with the closing of older ones, has declined significantly over the past decade, with more firms closing than starting for the first time in a quarter century.

Instead of stemming from the grassroots, the recovery after the latest crash was led, unlike in previous expansions, by larger firms while small company hiring remained relatively paltry. Self-employment rose, but increasingly this took the form of sole proprietorships as opposed to expanding smaller companies with employees. By 2013, smaller firms with under one hundred employees added far fewer jobs than in the prior decade. Unlike prior post-war recoveries, since 2007, grassroots companies did not lead the way out of recession and continued to lose ground compared with larger companies that either could afford the costs or avoid the taxes imposed by, the Clerical regime.

This decline in entrepreneurial activity marks a historic turnaround. In 1977, SBA figures show, Americans started 563,325 businesses with employees. In 2009, they started barely 400,000 Business start-ups, long a key source of new jobs, have declined as a portion of all businesses from 50 percent in the early 1980s to 35% in 2010.

There are many explanations for this decline, including the impact of offshoring, globalization and technology. But some reflects the impact of the ever more powerful Clerical regime, whose expansive regulatory power undermines small firms. Indeed, according to a 2010 report by the Small Business Administration, federal regulations cost firms with less than 20 employees over $10,000 each year per employee, while bigger firms paid roughly $7,500 per employee. The biggest hit to small business comes in the form of environmental regulations, which cost 364% per employee more for small firms than large ones. Small companies spend $4,101 per employee, compared to $1,294 at medium-sized companies (20 to 499 employees) and $883 at the largest companies, to meet these requirements.

The nature of federal policy in regards to finance further worsened the situation for the small-scale entrepreneur. The large “too big to fail” banks received huge bailouts, but have remained reluctant to loan to small business. The rapid decline of community banks, for example, down by half since 1990, particularly hurts small businesspeople that depended on loans from these institutions.

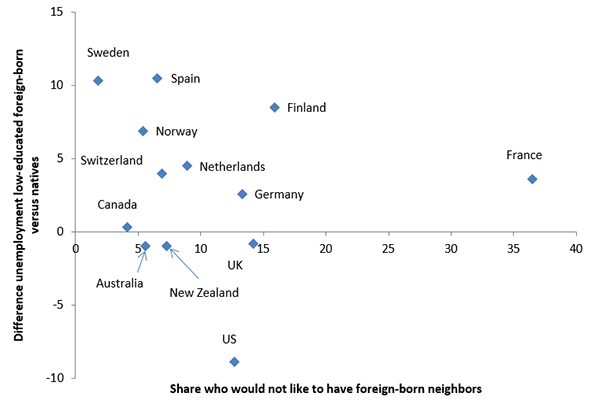

The Descent of the Yeomanry, with Cheers from the Clerisy

Despite America’s egalitarian roots, the prospect of mass downward mobility has been embraced widely by some business oligarchs and much of the Clerisy. The future being envisioned is one dominated by automated factories and computer-empowered service industries that will continue to pressure both jobs and wages in the future. In this scenario, productivity will rise, but wages may stagnate or decline. This leads some to propose that the American middle and working classes has become economically passé. Steve Case, founder of America Online, has even suggested that future labor needs can be filled not by current residents but by some thirty million immigrants.

Arguably the first group to feel the downward pressure has been blue collar workers, whose lot has declined over the past few decades. After World War Two, as the United Autoworkers’ Walter Reuther noted, “the union contract became the passport to a better life” that was creating “a whole new middle class.” But with the shifting of industry overseas and the decline of private sector unions, the path for blue collar workers to enter the middle class has become more difficult.

Although they often claim to defend the middle class, the political stance adapted by the Clerisy, as well as the tech oligarchs and the investors, tends to worsen this trajectory. Environmental concerns impose themselves most against basic industries such as fossil fuels, agriculture and much of manufacturing. These employ many in highly paid blue-collar fields, with average salaries of close to $100,000. In the last decade, top U.S. firms, notes the liberal Center for American Progress, have cut almost three million domestic jobs. Automation also leads to the diminution of traditional white collar professions as well as the shift of high-end service jobs offshore.

Overall, it has become increasingly common to regard the middle class as threatened and even doomed. Indeed, as early as1988 Time magazine featured a cover story on the “declining middle class,” which at that time was considerably more healthy than today. After the great recession, the American blue-collar worker has been pitied, but certainly not helped by the clerisy, which believes that there is no hope for manufacturing or similar outmoded jobs in an information age. Blue collar workers were described in major media as “bitter,” psychologically scarred” and even an “endangered species.” Americans, noted one economist, suffered a “recession” but those with blue collars endured a “depression.”

This perspective extends across ideological lines. Libertarian economist Tyler Cowen suggests that an “average” skilled worker can expect to subsist on little but rice and beans in the future U.S. economy. If they choose to live on the East or West Coast, they may never be able to buy a house, and will remain marginal renters for life. Left-leaning Slate in 2012 declared that manufacturing and construction jobs, sectors that powered the yeomanry’s upward mobility in the past, “aren’t coming back. Rather than a republic of yeoman, we could evolve instead, as one left-wing writer put it, living at the sufferance of our “robot overlords,” as well as those who program and manufacture them, likely using other robots to do so.

Contempt for the middle class is often barely concealed among those most comfortably ensconced in the emerging class order. Financial Times columnist Richard Tomkins declared that the middle class, “after a good run” of some two centuries, now faces “relative decline” and even extinction. This historical shift towards mass downward mobility elicited only derision, not concern: “Classes come and classes go” and that when the middle orders disappears about the only ones that will be sorry to see them go might be the “middle classes themselves. Boo hoo.”

The Rise of the Yeomanry

This reversal in class mobility and the slowing diffusion of property ownership in America, if not addressed, threatens to undermine the country’s traditional role as beacon of opportunity. Equally important, the diminution of the middle orders threatens one of the historic sources of economic vitality and innovation.

The roots of America’s middle class reflects the critical role such small holders have played throughout history. Dynamic civilizations tend to produce more than their share of “new men.” But nowhere was this middle class ascendency more dramatic than in Europe, first in Italy and later in northern Europe.

Initially, this was a comparatively small, outside group, with much of the activity conducted by outsiders such as Jews and, later, Christian dissenters. They were the driving force of the expanding capitalist market, the creators of cities and among the primary beneficiaries of economic progress. Peter Hall quotes a historian of 15th Century Florence:

Apprentices became masters, successful craftsmen

became entrepreneurs, new men made fortunes in

commerce and money-lending, merchants and bankers

enlarged their business. The middle class waxed more

and more prosperous in a seemingly inexhaustible boom.

These “new men,” which included some landless peasants, gradually overthrew the old artisan-like traders, eventually supplanted the aristocracy, and in some instances, the royal families as well. In most cases, their ascendency, although at times exploitative, generally promoted the expansion of both freedom and individual choice. They also were among the first commoners to seek out land, often in the periphery, in part as a business decision, but also to mimic the lifestyles of the traditional aristocracy.

As occurs in every economic transition some benefited some at the expense of others. Some “new men” from peasant and artisan backgrounds rose, but many others became part of an impoverished proletariat. Many urban artisans lost their jobs to machines, but many others used their expertise to move into the middle class, often through technical innovations that, in the words of the French sociologist Marcel Mauss, constituted “a traditional action made effective, ”notably in agriculture, metallurgy and energy.

As a colony of Britain, the Americans reflected that island’s rapid ascendancy of small holders in the 17th and 18th Century, which linked liberation from feudalism with a less hierarchical order and the dispersion of ownership. The rise of the yeoman class in Britain was particularly critical in foreshadowing the evolution of America. These small landowners played a critical role in the overthrow of the monarchy under Cromwell, and consistently pushed for greater power for those outside the gentry.

Yet ultimately many paid a great price for liberal reform, allowing for enclosures of what had been communal pasture; in the process productivity rose. Some benefited, becoming gentry themselves, while many smallholders lost their lands, and flowed into the towns where they joined the swelling proletariat. Others, notably large merchants, bought political influence and marriage into old families. By 1750, according to Marx, the Yeomanry had disappeared, a claim denied by some who believed this class persisted, albeit weakened, well into the 19th Century.

The American Model

Many of these displaced yeoman found a more opportune environment in America, where diffusion of ownership, as both Jefferson and Madison noted, remained central to the very concept of the nation. Small holders served, in the words of economic historian Jonathan Hughes, as “the seat of Republican government and democratic institutions.”

America’s focus on dispersed ownership was further enhanced by government actions throughout the country’s history. In contrast to their counterparts in Britain, the yeomanry in the United States enjoyed access to a greater, and still largely economically underutilized land mass, as well as a persistently growing economy. “In America,” de Tocqueville noted, “land costs little, and anyone can become a landowner.”

The Homestead Act was signed by President Lincoln in 1862. By granting land to settlers across the Western states, Lincoln was extending the notion of what historian Henry Nash Smith described as a “agrarian utopia” ever further into the continental frontier. Yet in reality the Homestead Act, which offered for a $.25 registration fee $1 per 160 acres proved more symbolic than effective, impacting perhaps at most two million people in a nation over 30 million. Railways, using their land grants, actually sold more land than the government gave away.

The westward expansion of the Republic created huge opportunities for expansion of land ownership. Jefferson wanted the land sold to the public to be a source of one-time revenue and a permanent holding for the buyer. In many ways, at least until the 1890s, a far higher proportion of Americans owned land—almost 48%—than countries such as Britain where ownership was far more concentrated. These lands, not surprisingly, also became the source of often wild speculative booms and busts, both on the agricultural frontier and the burgeoning cities.

Many factors ultimately undermined the first old agrarian Jeffersonian dream. Capitalist-led industrial growth shifted the proportion of the population living in cities. Only 5 percent in 1790, it rose to almost 20 percent in 1850, and nearly 40% by 1900. The new order, as in England, also weakened the position of the old artisanal professions, which often made up the ranks of the small scale owners; in many cases they were replaced by women, children and new migrants, from the countryside or from abroad. They became, as the British reformist paper The Morning Star wrote, “our white slaves, who are toiled onto the grave, for the most part silently pine and die.”

The movement into cities, and the industrial economy, turned many workers from owners to renters. In the new industrial centers, it became far harder to start a business or own property. Even white collar workers often lost out as the instrumental economic rationality of capitalism displaced a more locally focused economy based on tradition, religion and small-scale production.

In the United States, conditions were generally less gruesome than in Britain or the rest of Europe, but this did not slow the tendency towards ever great concentration of ownership. The rise of great entrepreneurs like Morgan, Vanderbilt, and Carnegie drove parts of the economy into the hands of a relative handful of people. This concentration of power and land ownership engendered a powerful protest in both rural and urban areas. Henry George’s influential Progress and Poverty, published in 1879, maintained that “the ownership of land” was the “fundamental fact” determining the social, political and “moral condition of a people.” Land, he asserted, should be owned by the public and government funded by rents.

George’s approach appealed to a population that was seeing land ownership slipping from their grasp. Even on the land, as farming itself modernized, there was a gradual shift , as farms mechanized and markets became more global, toward tenancy; by 1900 one in three American farmers were landless tenants. The concentration of property ownership continually grew from the 1870s on well into the 1920s.

By the early 20th century, as the original rustic yeoman dream was weakening, there was increased pressure for change from the growing urban population. Much of the pressure came from a middle and upper-middle class who felt threatened by the concentration of ownership and political power in the hands of the industrial and financial oligarchies.

The Homeownership Revolution

As the nation moved from its agricultural roots, the yeoman class interest in property would find a new main expression in the form of homeownership. This would represent an opportunity both to escape the crowded city or, for the migrant from rural areas, live in a less dense urban environment. This drive was supported by both conservatives and New Dealers, who promulgated legislation that expanded homeownership to record levels. “A nation of homeowners,” Franklin Roosevelt believed, “of people who own a real share in their land, is unconquerable.”

The great social uplift that occurred then, coming to full flower after the Second World War, saw a working class—not only in America but in Europe and parts of east Asia—now enjoying benefits before available only to the affluent classes. In 1966, author and New Yorker reporter John Brooks observed in his The Great Leap: The Past Twenty-Five Years in America, that, “The middle class was enlarging itself and ever encroaching on the two extremes—the very rich and the very poor.” Indeed, in the middle decades of the 20th Century, the share of income held by the middle class expanded while that of the wealthiest actually fell.

New Deal legislation—the Housing Act of 1934, creation of the Federal Housing Administration (FHA) and the Federal National Mortgage Association, or Fannie Mae—set the stage for the great housing boom of the 1950s. This was further augmented by the GI bill, which also provided low-interest loans to returning veterans. The success of the private financial and construction interests who benefited from this boom, suggests author Eric John Abrahamson, was largely fostered by what he describes as a “planned” economy that consciously sought to expand ownership both during the New Deal and particularly in ensuing decades. Almost half of suburban housing, notes historian Alan Wolfe, depended on some form of federal financing. This egalitarian impulse was in part driven by people returning from WW II and Korea, many of whom benefited from the GI Bill.

This resulted in an unprecedented dispersion of property ownership. This process was aided by a strong economy and the expansion of automobile ownership, which greatly expanded the yeomanry’s mobility. Increasing numbers of the middle class and even working class people become homeowners, sparking an enormous surge in home building. By 1953, the number of Americans owning their own homes climbed to twenty-five million, up from eighteen million in 1948. A country of renters was transformed into a nation of owners. Between 1940 and 1960 non-farm homeownership rose from 43 percent to over 58 percent. It was an accomplishment of historic proportions, notes historian Abrahamson, of “a transformed Jeffersonian vision.”

New Class Conflict Over the form and Nature of Growth

In recent decades, this vision of widening prosperity and property ownership has become increasingly threatened, as most evidenced by the housing bust of 2007-8. It also has come under increased attack from among the ranks of the clerisy. To be sure, many of those who bought homes in the last decade were not economically prepared, as some analysts suggest. But in the wake of the housing bust, the attack on homeownership expanded to include not only planners and pundits, but even parts of the investment community have seen in the yeomanry’s decline an opportunity to expand the base of renters for their own developments.

The ideal of homeownership, particularly in the suburbs, have long raised the ire of many academics and intellectuals in particular . Some have sought to de-emphasize increased wealth and seek instead to embrace what they consider a more moral, even spiritual standard. This movement, not so far from old feudal concepts, had its earliest modern expression in E.F. Schumacher’s 1973 influential Small is Beautiful and the writings of London School of Economics’ E.J. Mishan.

Both writers rightly criticized the sometimes cruelly mechanistic nature of much technological change, but also revealed a dislike of the very kind of expansive growth that has lifted so many into the yeoman class after the Second World War, not only in America but in Europe and parts of East Asia. “The single minded pursuit for individual advancement, the search for material success,” Mishan wrote, “may be exacting a fearful toll on human happiness.”

In the search for an alternative, both writers looked not forward, but backwards. Schumacher described “the good qualities of an earlier civilization”, that is, the old rural English society identified not so much with progressivism, or socialism, but the old Tory class order.

More recently, many advocates of slow, or no growth are finding inspiration in even less enlightened settings than old England. Some point to the small Himalayan kingdom of Bhutan, the site of a 2014 pilgrimage by Oregon Gov. John Kitzhaber . This “happiness” poster child makes an odd exemplar for the 21st century. In contrast to the praise heaped on the tiny nation by Kitzhaber, one Asian development expert recently described the country as ”still mired by extreme poverty, chronic unemployment and economic stupor that paints a glaring irony of the ‘happiness’ the government wants to portray.” In this “happiest place on earth” one in four lives in poverty, nearly forty percent of the population is illiterate and the infant mortality rate is five times higher than in the United States. It also has a nasty civil rights record of expelling its Nepalese minority of the country.

Bhutan, of course, is a pastoral country, but some urbanists also increasingly apply their “happiness” ideal to cities, particularly poorer ones. Canadian academic Charles Montgomery, for example, celebrates what he sees as high levels of happiness in the city slums of developing countries. Montgomery points to impoverished Bogota, for example, as “a happy city” that shows the way to urban development. If we can’t do a Bhutanese village, maybe we can be compelled to evacuate suburbia for the pleasures of life in some thing that more reflects life in a crowded favela.

Although this emphasis on happiness certainly has its virtues, and should be a consideration in how a society grows, lack of economic growth, and low levels of affluence, seems an unlikely way to make people more content. Recent research, in fact, finds that, for the most part, wealthier countries are not only richer but happier than those assaulted by poverty. Indeed the happiest countries are not impoverished at all, according to the Earth Institute, but highly affluent countries led by Denmark, Norway, Switzerland, the Netherlands and Sweden; the lowest ranked countries were all very low-income countries in Africa.

The argument against growth has gained currency with the rise of environmentalism, long focused, often with justification, on the negative impacts of economic expansion. This has engendered an understandable search for an alternative standard to measure societal well-being. Climate change campaigners such as The Guardian’s George Monbiot than “a battle to redefine humanity” , essentially ending the era of “expanders” with that of “restrainers.” Some economists, particularly in Europe, have embraced the notion of what they call “de-growth,” that is a planned, ratcheting down of mass material prosperity.

Winners and Losers in the ‘Happiness’ Game

In any conflict over the preferred shape of society, there are winners and losers. The shift from a focus on growth to one on what is fashioned as sustainability has proven a boon both for the public sector, particularly those working in regulatory agencies and politicians who now have new ways to elicit contributors, and those parts of the private sector that work most closely with government. Other beneficiaries include connected investors, including many who benefit from “green” energy subsidies that, particularly when measured by their production of energy, are considerably higher than those secured over the past century by oil and gas interests.

The downsizing of growth, naturally, also appeals to many who already enjoy wealth, such as Ted Turner, who then promote anti-growth policies through their foundations, and, as a bonus, get to feel very good about themselves. Other winners include the media Clerisy, notably in Hollywood–who propagandize such views while living in unimaginable luxury—as well as academics. The successful and well-compensated producer and director James Cameron complains about “ too many people making money out of the system” and warns that growth must stop to save the planet.

So who loses in the new anti-growth regime? Certainly these include large parts of the working class—farmworkers, lumberjacks, factory operatives, oil field workers and their families—who work in extractive industries most subject to regulatory constraints and higher energy prices. Particularly hard hit may well be young families who, perhaps forsaking the “slacker” life, now find their aspirations of a house and decent job blocked by the generally older, and better off, advocates for “happiness.”

Wall Street and “Progressives” find Common Ground

The rise neo-Feudalism, and the decline of the yeomanry is best understood as the consolidation of ownership in ever fewer hands. This process has been greeted with enthusiasm by financial hegemons, who have stepped in with billions to buy foreclosed homes and then rent them; in some states this has accounted for upwards of twenty percent of all new house purchases. Having undermined the housing market with their “innovations,” notably backing subprime and zero down loans, they now look to profit from the middle orders’ decline by getting them to pay the investment classes’ mortgages through rents.

In the wake of the housing bust, and the longer than expected weak economy following the Great Recession, many financial analysts have insisted that we were headed towards a “rentership society” as homeownership rates plunged from historic highs in the three years following the crash. Part of this shift has been exacerbated by the movement of large investment groups like Blackstone to buy up single family houses for rent, representing a kind of neo-feudalist landscape, where landlords replace owner occupiers, perhaps for the long-run.

The impact of the investor move into housing has had a negative effect on middle and working class potential buyers who find themselves frequently outbid by large equity firms.” There is the possibility that Wall Street and the banks and the affluent 1 percent stand to gain the most from this,” said Jack McCabe, a real estate consultant based in Deerfield Beach, Fla. “Meanwhile, lower-income Americans will lose their opportunity for the American Dream of building wealth through owning a home.”

But, however convenient these developments may prove to investors on Wall Street, for society and the future of the democracy, the concentration of ownership in fewer hands is highly problematical. Rather than the yeoman with his own place, and the social commitment that comes with it, we could be creating a vast, non-property owning lower class permanently forced to tip its hat—and empty its wallet—for the benefit of his economic betters.

One would expect that this diminution of the middle class would offend those on the left, which historically supported both the expansion of ownership and the creation of a better life for the middle class. Yet some progressives, going back to the period before the Second World War, have disliked the very idea of dispersed ownership; many intellectuals, notes Christopher Lasch, found a society of “small proprietors” and owners “narrow, provincial and reactionary.”

Increasingly, the media and many urbanists, who see a new generation of permanent renters as part of their dream of a denser America, also embrace this vision as being more environmentally benign than traditional suburban sprawl.

The very idea of homeownership is widely ridiculed in the media as a bad investment and many journalists, both left and right, deride the investment in homes as misplaced, and suggest people invest their resources on Wall Street, which, of course, would be of great benefit to the plutocracy. One New York Times writer even suggested that people should buy housing like food, largely ignoring the societal benefits associated with homeownership on children and the stability communities. Traditional American notion of independence, permanency and identity with neighborhood are given short shrift in this approach.

This odd alliance between the Clerisy and Wall Street works directly against the interest of the middle and aspiring working class. After all, the house is the primary asset of the middle orders, who have far less in terms of stocks and other financial assets than the highly affluent. Having deemed high-density housing and renting superior, the confluence of Clerical ideals and Wall Street money has the effect on creating an ever greater, and perhaps long-lasting, gap between the investor class and the yeomanry.

This piece originally appeared at The Daily Beast.

Joel Kotkin is executive editor of NewGeography.com and Distinguished Presidential Fellow in Urban Futures at Chapman University, and a member of the editorial board of the Orange County Register. His newest book, The New Class Conflict is now available for pre-order at Amazon and Telos Press. He is author of The City: A Global History and The Next Hundred Million: America in 2050. His most recent study, The Rise of Postfamilialism, has been widely discussed and distributed internationally. He lives in Los Angeles, CA.