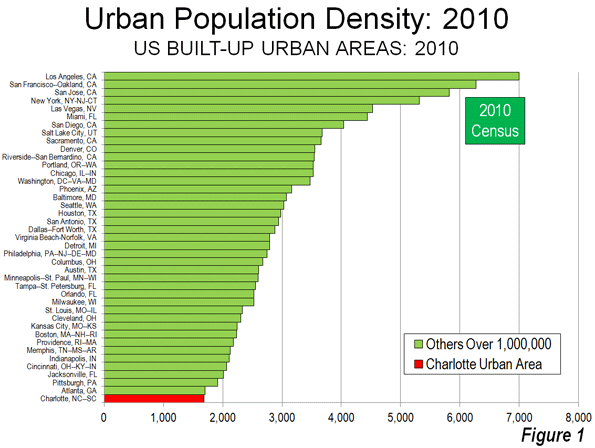

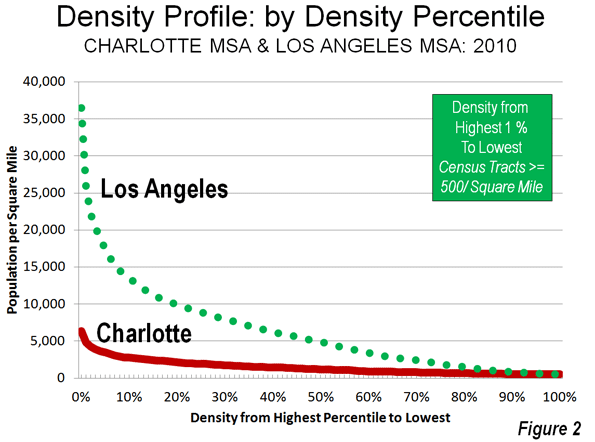

There may be no better example of the post World War II urban form than Charlotte, North Carolina (a metropolitan area and urban area that stretches into South Carolina). Indeed, among the approximately 470 urban areas with more than 1 million population, Charlotte ranks last in urban population density in the United States (Figure 1) and last in the world. According to the United States Census Bureau, Charlotte’s built-up urban area population density was 1685 per square mile (650 per square kilometer) in 2010. Charlotte is not only less dense than Atlanta, the world’s least dense urban area with more than 4,000,000 residents, but it is only one-quarter the density of the supposed “sprawl capital” of Los Angeles (Figure 2).

Over the last seven decades, Charlotte also has been among the fastest growing metropolitan areas in the United States. Charlotte is the county seat of Mecklenburg County, and as recently 1940 as was home to 101,000 residents while with its suburbs in Mecklenburgh County was barely 150,000.

Declining Densities in the Core City

Charlotte is also in example of the difficulty of using the core municipality data for comparisons to the suburban balance of metropolitan areas. With North Carolina’s liberal annexation laws, Charlotte has pursued a program of nearly continuous annexation such that in every 10 years since 1940, the city has added substantial new territory.

In 1940, the city of Charlotte covered a land area of 19 square miles (50 square kilometers) and had a population density of 5200 per square mile (2,000 per square kilometer). For a prewar core municipality, this was not at all dense. For example, Evansville Indiana, which had approximately the same population at the time, had a population density nearly twice that of Charlotte. Other larger core municipalities approached triple or more Charlotte’s population density, such as Trenton, Buffalo, Providence, and Milwaukee.

Over the last seven decades, the city’s population has risen by 6.2 times, while its land area has increased by 14.4 times (Table $$$). The result is a 53% decline in the city of Charlotte’s population density, to 2456 per square mile (948 per square kilometer). This is only slightly above average density of the US built-up urban area – which includes the smallest towns and suburbs of every size – of 2,343 per square mile (1,455 per square kilometer). Indeed, the average far flung suburbs (30 miles distant) of Los Angeles, such as Pomona and Tustin, are more than 2.5 times as dense.

| City of Charlotte (Municipality) | |||||

| Population & Land Area: 1940-2010 | |||||

| Census | Population | Area: Square Miles | Area: Square KM | Density (Sq. Mile) | Density (KM) |

| 1940 | 100,899 | 19.3 | 50.0 | 5,228 | 2,019 |

| 1950 | 134,042 | 40.0 | 103.6 | 3,351 | 1,294 |

| 1960 | 201,564 | 64.8 | 167.8 | 3,111 | 1,201 |

| 1970 | 241,178 | 76.0 | 196.8 | 3,173 | 1,225 |

| 1980 | 314,447 | 139.7 | 361.8 | 2,251 | 869 |

| 1990 | 395,934 | 174.3 | 451.4 | 2,272 | 877 |

| 2000 | 567,943 | 242.3 | 627.6 | 2,344 | 905 |

| 2010 | 731,424 | 297.8 | 771.3 | 2,456 | 948 |

| Change | 625% | 1443% | 1443% | -53.0% | -53.0% |

Growth by Geography

The core city of Charlotte’s ever-fluctuating boundaries make it necessary to use smaller area measures to estimate the distribution of population growth. This can be accomplished using zip code data from the 2000 and 2010 censuses.

Inner Charlotte, for the purposes of this analysis (zip codes 28202 through 28208) covers approximately 28 square miles (73 square kilometers) and had a population of approximately 92,000 in 2010 . This is a larger area than the city of Charlotte in 1940, which covered only two thirds as much land area and had more people. Between 2000 and 2010, this inner area population rose by 6,200 residents. All the gain was in the central zip code that comprises the downtown area (central business district), which in Charlotte is called "Uptown." Outside this small 1.8 square mile area (4.7 square kilometers), the inner area actually lost 1,400 residents.

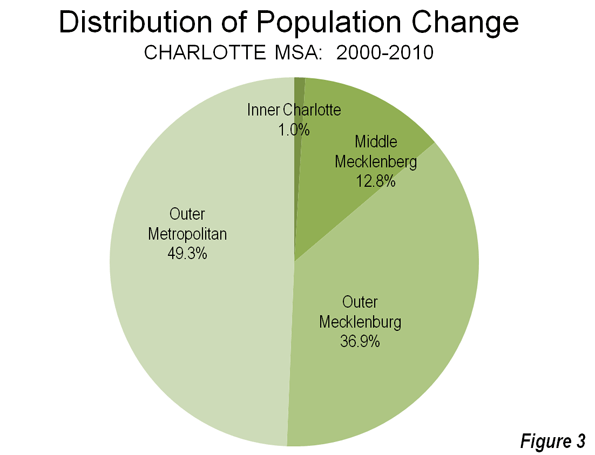

Overall, the inner area of Charlotte – which has somewhat an obsessive hold on many city leaders – accounted for 1.0% of the metropolitan area growth from 2000 to 2010. This is not unlike other major metropolitan areas, which have experienced slow growth, particularly in areas adjacent to the downtown cores. Among the 51 US metropolitan areas with more than 1,000,000 population in 2010, net gain occurred within two miles of city hall, while this gain was erased by a loss of 272,000 between two and five miles of city hall.

Another 13% (64,000) of the 2000-2010 growth occurred in the middle Mecklenburg County zip codes (28209 to 28217), virtually all of which is in the city of Charlotte. This 185 square mile area, combined with the inner area, exceeds the land area of the city in 1990.

Mecklenburg County’s outer zip codes, many of which are in the city, captured 37% of the metropolitan area’s growth (184,000). The remaining 49% (247,000) of growth in the Charlotte metropolitan area was outside Mecklenburg County (Figure 3).

From 1990 to 2010, Charlotte was the seventh fastest growing metropolitan area out of the 51 with a population exceeding 1 million. Early data for the present decade shows Charlotte to have slipped to ninth fastest growing; however during this period, Charlotte has displaced Portland, Oregon as the nation’s 23rd largest metropolitan area. Between 1990 and 2012, Charlotte added nearly 1,000,000 residents and now has 2.4 million residents.

Uptown: The Commercial Story

Unlike other post-World War II metropolitan areas (such as Phoenix, San Jose, and Riverside-San Bernardino), Charlotte has developed a concentrated, high rise downtown area." Part of this is due to the city’s strong financial sector. Charlotte is the home to Bank of America, the nation’s second largest bank and the successor to the San Francisco-based California bank of the same name that was the largest bank in the world for decades. Nation’s Bank, the predecessor to Bank of America, erected a 60 story tower in 1992 that was among the tallest in the United States.

Charlotte was also home to Wachovia Bank, which built its 42 floor headquarters before, and nearby the Bank of America Tower. Wachovia had intended to move to a larger, 50 story building. However, the time it was completed, Wachovia had been sold to Wells Fargo Bank, a casualty of the US financial crisis. The new building was renamed the Duke Energy Center.

Thus, Charlotte consumed one San Francisco bank, and lost another to San Francisco. Now Uptown Charlotte has six buildings more than 500 feet in height (152 meters). With six buildings of this height, Charlotte has developed by far the concentrated central business district among the newer metropolitan areas.

However, the high employment density has not converted into a transit oriented business district, as some might have predicted. American Community Survey (CTPP) data indicates that approximately 87% of uptown employees use cars to get to work. Further, more than 90% of the jobs in the metropolitan area are outside Uptown.

Uptown: The High Rise Condominium Story

Uptown’s commercial progress has not been replicated in the residential market, as overzealous high rise condominium developers apparently may have confused Charlotte for Manhattan or Hong Kong. One of the more recent 500 foot plus towers was The Vue, a 50 story condominium tower. Too few condominiums were sold, and a foreclosure auction followed. The new owner has converted the condominiums to rental units. A 40 story condominium project ("One Charlotte") was to feature units priced from $1.5 million to $10 million, but was cancelled. Another condominium building, the 32 story 300 South Tryon was also cancelled. A tower base was prepared for a 50 plus story condominium monolith, but this was never built, while depositors were claiming they could not find the developer to get their deposits back. It was also reported that legendary developer Donald Trump had plans for the tallest building in town, a 72 story condominium tower, which would have been joined by another tower. These have also been cancelled (for artists renderings, click here).

Charlotte’s Continuing Dispersion

While Uptown condominium developers were unable to sell many units, Charlotte’s labor market dispersed so much between 2000 and 2010 that the Office of Management and Budget expanded the metropolitan area by four counties. The net addition to the population of this revision was approximately 460,000. This is by far the largest percentage increase to a metropolitan area over the period, though much larger New York added counties with 660,000 residents.

Charlotte seems to say it all with respect to the ill-named "back to the city movement" (ill named, because most suburbanites did not come from the city to begin with). Yes, there is growth downtown and yes, it is important and yes, it is healthy. But, in the overall scheme of things, it is small, and relative to the rest of the thriving region, likely to remain less important in the years ahead.

Wendell Cox is a Visiting Professor, Conservatoire National des Arts et Metiers, Paris and the author of “War on the Dream: How Anti-Sprawl Policy Threatens the Quality of Life.

Photo: Uptown Charlotte courtesy of Wiki Commons user Bz3rk