Thou wouldst fain destroy the temple! If thou be Jesus, Son of the Father, now from the Cross descend thou, that we behold it and believe on thee when we behold it. If thou art King over Israel, save thyself then!

God, My Father, why has thou forsaken me? All those who were my friends, all have now forsaken me. And he that hate me do now prevail against me, and he whom I cherished, he hath betrayed me.

Lyric excerpts from the Fifth and Fourth and Words, respectively, of the Seven Last Words of Christ orchestral work by Joseph Haydn.

I’m pissed.

Ever since the announcement late Thursday that the City of Detroit was indeed going to file for Chapter 9 municipal bankruptcy protection, the Internet has been overflowing with commentary on the matter. The commentary has come from all places and taken on by all comers – from the political left and right; from hard news and general interest sources. And all usually with the same scripted and lazy tripe about how Detroit reached its nadir:

- Single-minded dependence on a collapsing auto industry doomed Detroit.

- An inability to diversify economically doomed Detroit.

- Public mismanagement and political corruption doomed Detroit.

- An inability to effectively deal with its racial matters doomed Detroit.

- The dramatic and total loss of its tax base doomed Detroit.

That’s it, people, they seem to reason. The Motor City’s fall from grace is as simple as that. You do the things Detroit did, and you get what Detroit got. You defer decisions just as Detroit did, and you too will suffer the consequences. The speed with which the various articles on Detroit came out proved to me that many writers anticipated the announcement with at least a twinge of glee.

As I’ve written before, Detroit’s narrative serves everyone else as the nation’s whipping boy, and that came through in the last couple of days:

You can find Detroit in Cleveland, St. Louis, Buffalo, Milwaukee, Baltimore and Philadelphia. You can find it in Indianapolis, Minneapolis, Cincinnati, Columbus and Louisville. You can find it in Atlanta, Miami, Houston, Dallas and Phoenix. You can even find it in Las Vegas, Seattle, San Francisco and Portland. And yes, you can definitely find it in New York, Chicago, Los Angeles and Washington, DC. You can find elements of the Detroit Dystopia Meme™ in every major city in the country. Yet Detroit is the only one that owns it and shoulders the burden for all of them.

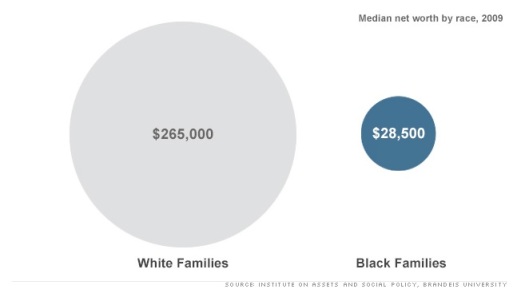

But let’s leave that aside. I’m pissed because no one seems to acknowledge the central reason Detroit is filing for bankruptcy now. It has endured abandonment – white flight abandonment – on an absolutely epic scale. Before there was auto industry collapse, before there was a lack of economic diversity, before there was mismanagement and corruption, there was abandonment. People skirt and dance around the issue when they talk about the loss of Detroit’s tax base. What Detroit lost was its white people. The chart above illustrates how Detroit’s unique experience when compared to similar cities.

Detroit is what happens when the city is abandoned. And frankly, there is a part of me that views those that abandoned Detroit with the same anger reserved for hit-and-run drivers – they were the cause of the accident, they left the scene of the crime, and they left behind others to clean up the mess and deal with the pain. What’s worse, so many observers seem to want to implicate those left behind – in Detroit’s case a large African-American majority community – for not cleaning up the mess or easing the pain. Their inflicted pain which they’ve made ours.

White abandonment of Detroit did not start with the 1973 election of Coleman Young as mayor, or even the 1967 riots, yet those two events accelerated the process. And indeed, Detroit had a very unique set of circumstances that caused it to veer down a troubled path. The very first piece featured in my blog was about the land use and governing decisions that were made more than one hundred years ago in Detroit that literally set the city’s decline in stone. I identified eight key factors:

- Poor neighborhood identification, or more broadly a poorly developed civic consciousness.

- A housing stock of poor quality, cheap and disposable, particularly outside of the city’s traditional core.

- A poorly developed and maintained public realm.

- A downtown that was allowed to become weak.

- Freeway expansion.

- Lack of or loss of a viable transit network.

- A local government organization type that lacked accountability at the resident/customer level.

- An industrial landscape that was allowed to constrain the city’s core.

Conor Friedersdorf of the Atlantic wrote perhaps one of the best recent articles I saw on Detroit when he acknowledged that even a half-century ago, journalists were predicting a dire future for the D. Take this quote Conor found from The Reporter, published October 31, 1957:

The auto industry created modern Detroit simply as its dormitory and workshop, attracted polyglot millions to it, used it, and now threatens to abandon it. Civic consciousness played little part in the lives of the masses of Irish, German, Poles and Italians who flocked to Detroit in search of a Ford or Dodge or Packard pay check, and who settled there in islands of their own – any more than it played a part in the managements of Ford or Dodge or Packard themselves, or in the crowd of Negroes who also descended upon the city during the boom years of the Second World War… Indeed, it is remarkable that any sense of civic responsibility at all should have been generated in so rootless and transient a community.

What can a city do when it finds its patron industry and its middle class moving out, leaving it a relic of extremes?… But urban deterioration offers at least one advantage. Once a city core has become as run-down as Detroit’s you can start to rebuild fairly cheaply.

Yes, that is from 1957.

The chart at the top of this article was done for an article I did more than a year ago, looking at U.S. Census data for several peer cities over the last seven decennial censuses. In it, I concluded that Detroit’s experience of abandonment was entirely unique:

Between 1950 and 1970, the decline in Detroit’s white population was on the low end of the spectrum of cities on this list, but it was in the ballpark. Prior to 1970, Detroit and St. Louis were the white flight laggards. After 1970, the bottom fell out and Detroit stood alone. While there certainly are economic reasons white residents may have had for moving, this graph may lend credence to the twin theories of Motor City white flight – the 1967 riots and the 1973 election of Mayor Coleman Young.

I’m not trying to persuade anyone of the invalidity of their decision to move from Detroit. There were good reasons and not so good reasons. I’m only trying to describe its impact relative to other cities. And where exactly are those white residents who left over the last 60 years? Certainly many have passed on. Some are currently in the Detroit suburbs or elsewhere in Michigan. Some are part of that great Detroit Diaspora that took them to New York, Washington, Charlotte, Atlanta, Houston, Phoenix, Los Angeles, Seattle and Portland. There are clearly at least 1.5 million reasons why white residents left Detroit.

But the fact is, had Detroit experienced white flight at the same combined rate as the other cities on this list, and not experienced any other changes, there would be nearly 350,000 more white residents today. Maybe 140,000 more households. Maybe more stable neighborhoods.

Can you imagine that? An additional 350,000 residents means Detroit would still be a city with more than one million people. It would likely be viewed in the same way that a Philadelphia or Baltimore is now – challenged but recovering – instead of the urban dystopia it’s widely seen as today. What impact would that have had on the city’s economy? On the metro area’s economy? On the state’s economy? Or simply the city’s national perception?

I’ve mentioned here on several occasions that the reason I chose the planning profession is because I grew up in Detroit during the 1970s. I looked around and saw a city with an inferiority complex and saw people leaving in droves. My naïve and childish thinking was, “instead of leaving the city, why don’t people stay and work to make it better?”

Silly of me. Abandonment is the American way.

Nonetheless, I view Detroit’s bankruptcy announcement positively. It acknowledges that its troubles are far deeper than most realize. It can be the springboard for fiscal recovery, a re-imagining of the city and an actual and complete revitalization. Detroit indeed is in uncharted waters, and its abandonment means that in many respects it could be viewed as a frontier city once again. I would not be surprised if, after restructuring and reorganization, after recapturing its innovative spirit, the city could see growth almost like it did at the beginning of the twentieth century, mimicking what, say, Las Vegas has done for the last 40 years. Even at this dark moment, Detroit has assets that are the envy of other cities.

But let no one forget that it is abandonment that brought Detroit to this point.

This piece originally appeared at The Corner Side Yard.

Pete Saunders is a Detroit native who has worked as a public and private sector urban planner in the Chicago area for more than twenty years. He is also the author of "The Corner Side Yard," an urban planning blog that focuses on the redevelopment and revitalization of Rust Belt cities.