“’Angry young men’ lack optimism.” This was the title of a BBC News story earlier this year, exploring the deeply pessimistic views that some young working class British hold about their own future. Two-thirds of the young men from families of skilled or semi-skilled workers, for example, never expect to own their own home. Angry young men, this time of immigrant origin, were also recently identified as the group causing riots in Swedish suburbs such as Husby. As Swedish Prime Minister Fredrik Reinfeldt noted, the riots were started by a core of “angry young men who think they can change society with violence”.

The social unrest occurring in Western Europe is often ascribed to the lack of integration into society among immigrants. It is true that dependency of public handouts rather than self-reliance has become endemic in Europe’s well‑entrenched and extensive welfare states. In Norway for example, the employment rate of immigrants from Asia is only 55 percent, compared to 70 percent for the non-immigrant population. Amongst African immigrants the figure is merely 43 percent. In neighboring Sweden, a recent government report noted that the employment rate of Somalians was merely 21 percent. This can be compared to 46 percent in Canada and 54 percent in the US for the same group. The low incentives for transitioning from welfare to work in Sweden and Norway compared to in Canada and the US explain at least part of this difference.

But a failure of integration is hardly the sole explanation for the social unrest which extends well beyond immigrant youth. Why not add another relevant perspective to the puzzle, namely the increasing marginalization that some young men feel across the continent? This frustration is hardly an excuse for violence, but relates to important social phenomena which deserve to be explored, and targeted with the right policies.

Youthful exclusion from the labor market constitutes a major challenge to European economies. Unemployment for European youth is in many countries more than twice the level of adult workers. The youth unemployment in advanced economies is, according to the International Labour Organization, estimated at an average level of 18 percent. Some countries, such as Switzerland, Austria and Germany, fare relatively well with a rate below ten percent. In others, such as the UK, France and Sweden, around one in five of the youth is unemployed. In Spain and Greece the share recently peaked at a rate of one in two.

It is hardly news that youth who face unemployment have a tendency to become angry, and to translate this anger to violence. What has become increasingly evident is how much this situation pertains particularly to men.

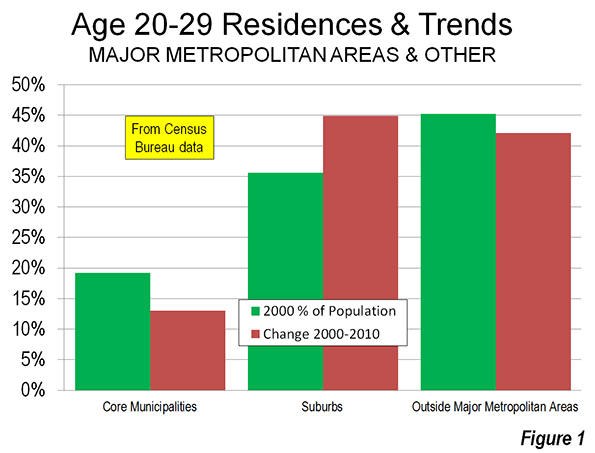

To begin with we can see that a number of societal trends in particular favor women’s career opportunities. Girls tend to perform better in school, regardless of class, place of residence or ethnicity. Young women also, not only in developed countries but even globally, now constitute the majority of students in higher education. Another important change which in particular benefits women’s career opportunities is urbanization. Large cities attract talented young people like magnets. The attraction tends to be greatest for young women, who find employment and opportunities for entrepreneurship in the sprawling service sectors. Men who remain behind in less densely populated areas sometimes struggle to find both work and a spouse.

As a whole, we have little reason to feel sorry for men in the labor market. Since women still take the primary responsibility for children and family, men can on average invest much more time on their careers and thus more often reach the top. But while some men succeed, others fall behind. Men end up dominating not only the top of society but also the bottom. After having failed in school, many men face rejection in both the labor market and the marriage market. They are left with little in terms of social capital, in terms of valuable know-how and established social networks.

One reason for why frustration grows is that for men the link between success in work and success in finding a partner is very strong. Men without higher education for example face a higher chance of never becoming a parent, whilst men with higher degrees face the lowest chance (the relation is the opposite for women, where the individuals with higher education face the highest risk of remaining childless). Extreme opinions, racism and violence are not uncommon among young men who feel they have little chance of making their way in society.

We should of course stress individual responsibility. But awareness of the alienation felt by some young men has the danger of morphing into a considerable long-term problem, even in wealthy European nations. In previous generations, a considerable amount of “simple jobs" existed in manufacturing, forestry, agriculture and the like which were suited for young individuals with limited education. Today, such jobs are far less available.

Part of the explanation is that technological changes and increasing global competition are pushing the labor market towards higher degree of specialization. Another reason is that policies in many modern countries, due in part to bureaucratic regulation, work to slow industrial development. Although industrial job growth is clearly possible and very promising in developed nations, many politicians wrongly believe that new industry has no future in rich Europe.

The lacking interest to open up for growth in manufacturing is combined with the fact that education systems in countries such as the UK and Sweden are not good at encouraging students with low academic interest to ready themselves for manufacturing and other technical jobs – the situation is much different in for example Germany and Switzerland, with promising apprentice systems. In addition a strong social stigma has begun to become associated with not having a higher degree. This prompts individuals to choose even university courses that aid them little if any on the labor market, rather than take available simple jobs and climb the career ladder by developing practical knowledge.

Frustrated young men should never be excused in their acts of violence. But we must take their lack of hope seriously. Both policies and the education system should be reformed, so that the simple entry-level jobs that are suited for young men who lack academic skills or interest are opened up. Such policies would as an added bonus boost growth, employment and in particular benefit smaller cities and rural regions. We surely need ample policies to boost women’s’ career opportunities and entrepreneurship, but we should also recognize the challenges tied to the increasing marginalization for the men who feel little hope of progressing in society by following the rules.

Dr. Nima Sanandaji is a Swedish author of Kurdish-Iranian origin. He has written two books about womens carreer opportunities in Sweden, and is upcoming with the report “The Equality Dilemma” for Finnish think-tank Libera.

Husby riot photo by Wiki Commons user Telefonkiosk.