Sitting around a table at a hookah bar in New York’s East Village with three women and a gay man, all of them in their 20s and 30s and all resolved to remain childless, a few things quickly became clear: First, for many younger Americans and especially those in cities, having children is no longer an obvious or inevitable choice. Second, many of those opting for childlessness have legitimate, if perhaps selfish, reasons for their decision.

“I like seeing people with their children, because they have their special bond, and that’s really sweet, but it’s not something I look at for myself,” says Tiffany Jordan, a lively 30-year-old freelance wardrobe stylist who lives in Queens in a rent-stabilized apartment and dates a man who “practically lives there.”

Jordan and her friends are part of a rising tide. Postfamilial America is in ascendancy as the fertility rate among women has plummeted, since the 2008 economic crisis and the Great Recession that followed, to its lowest level since reliable numbers were first kept in 1920. That downturn has put the U.S. fertility rate increasingly in line with those in other developed economies—suggesting that even if the economy rebounds, the birthrate may not. For many individual women considering their own lives and careers, children have become a choice, rather than an inevitable milestone—and one that comes with more costs than benefits.

“I don’t know if that’s selfish,” says Jordan, the daughter of an Ecuadoran and an Ohioan who grew up in the South Bronx, explaining her reasons for a decision increasingly common among women across the developed world, where more than half of the world’s population is now reproducing at below the replacement rate. “I feel like my life is not stable enough, and I don’t think I necessarily want it to be … Kids, they change your entire life. That’s the name of the game. And that’s not something I’m interested in doing.”

The global causes of postfamilialism are diverse, and many, on their own, are socially favorable or at least benign. The rush of people worldwide into cities, for example, has ushered in prosperity for hundreds of millions, allowing families to be both smaller and more prosperous. Improvements in contraception and increased access to it have given women far greater control of their reproductive options, which has coincided with a decline in religion in most advanced countries. With women’s rights largely secured in the First World and their seats in the classroom, the statehouse, and the boardroom no longer tokens or novelties, children have ceased being an economic or cultural necessity for many or an eventual outcome of sex.

But those changes happened quickly enough—within a lifetime—that they’ve created rapidly graying national populations in developed, and even some developing, countries worldwide, as boomers hold on to life and on to the pension and health benefits promised by the state while relatively few new children arrive to balance their numbers and to pay for those promises.

Until recently that decrepitude has seemed oceans away, as America’s open spaces, sprawling suburbs, openness to immigrants, and relatively religious culture helped keep our population young and growing. But attitudes are changing here as well. A plurality of Americans—46 percent—told Pew in 2009 that the rising number of women without children “makes no difference one way or the other” for our society.

These changes are not theoretical or inconsequential. Europe and East Asia, trailblazers in population decline, have spent decades trying to push up their birthrates and revitalize aging populations while confronting the political, economic, and social consequences of them. It’s time for us to consider what an aging, increasingly child-free population, growing more slowly, would mean here. As younger Americans individually eschew families of their own, they are contributing to the ever-growing imbalance between older retirees—basically their parents—and working-age Americans, potentially propelling both into a spiral of soaring entitlement costs and diminished economic vigor and creating a culture marked by hyperindividualism and dependence on the state as the family unit erodes.

Crudely put, the lack of productive screwing could further be screwing the screwed generation.

Consider contemporary Japan, which after decades of economic stagnation has become the most aged big country on the planet. Since 1990 the world’s third-largest economy has had more people over 65 than under 15; by 2050 it’s projected there will be more people over 80 than under 15. More than one in three Japanese women, predicts sociologist Mika Toyota, will never marry or have children (childbearing outside of marriage is still relatively rare in Japan and other wealthy Asian countries).

The results haven’t been pretty. In some places in Japan, particularly in the countryside, there are already too few working adults remaining to take care of the elderly, and kodokushi, or “lonely death,” among the aged, the unmarried, and the childless, is on the rise. Long a model of frugality, the demographically declining nation now has by far the high-income world’s highest rate of public indebtedness as spending on the elderly has shot past what the state can extract from its remaining productive workers. Last month, the nation’s new finance minister, Taro Aso, outright said that the elderly should be given grace to “hurry up and die.” This situation will not be made better by a desexualized younger Japanese generation: one in three young men ages 16 to 19 express “no interest” in sex—and that may be a good thing, given that 60 percent of young women of the same age share their indifference.

Europe may lag in sexual indifference, but its fertility rate—or births per woman—is around 1.5, also well below the replacement rate of 2.1. In Germany, the fertility rate has stagnated at around 1.4 for 40 years, despite vastly expensive attempts by the state to bribe potential mothers and reverse the problem of schrumpfnation Deutschland, or “shrinking” Germany. Thirty percent of German women say they do not intend to have children, and 48 percent of German middle-aged men now contend that they could have a happy life without children—three times as many as among their fathers.

While postfamilialism isn’t nearly as far along in the U.S., American marriage is faltering—and the baby is being thrown out with the bath water. Forty-four percent of millennials agree that marriage is becoming “obsolete.” And even among those who support tying the knot (including many of those who say it’s obsolete), just 41 percent say children are important for a marriage—down from 65 percent in 1990. It was the only factor to show a significant decline. (Others, such as sharing chores, sexual relationship, and sharing politics, either held steady or were seen as increasingly important.) On the flip side of the coin, the percentage of adults who disagreed with the contention that people without children “lead empty lives” has shot up, to 59 percent in 2002 from 39 percent in 1988.

Even before the 2008 crash, childlessness among American women ages 40 to 44 of all races and ethnicities had steadily increased for a decade, with the proportion of childless women doubling from 10 percent in 1980 to 20 percent today. But the negative trend has accelerated since the Great Recession began. In 2007 the fertility rate in America was 2.12 and had been holding nearly steady for decades at about replacement rate—the highest level of any advanced country. In just half a decade since, the rate has dropped to 1.9, the lowest since 1920 (when reliable records began being kept) and just half of the peak rate in 1957, in the midst of the baby boom, according to the Pew Research Center. Now projections of future U.S. population growth are diving, with the census estimate for 2050 down almost 10 percent from the mark predicted in 2008.

Making the trend even more worrisome, the sharpest drop in fertility and birthrates came from immigrants, particularly Hispanics, who hitherto have been responsible for much of our continued population growth. But that unique advantage seems to have ended, with net migration from Mexico to the U.S. having stopped or possibly even reversed since 2008, according to Pew. Mexico’s own fertility rate has plunged, from 7.3 in 1960 to 2.4 today; among immigrants, the rate drops to the American norm in just a generation.

In the short run, the falling birthrate has coincided with the emergence, for the first time, of the single and childless as a self-aware, powerful, and left-leaning political constituency. Yet what’s proven good for the Democratic Party may not be so good for the country in the long term. Even using the more optimistic 2008 projections, the proportion of retirees to working Americans—sometimes called the “dependency ratio”—is likely to rise to 35 retirees for every 100 workers in 2050, twice today’s ratio. That sets the stage for a fight over debt, austerity, benefits, and government spending that will make the vicious battles of the last four years seem more like, well, a tea party.

Of course, the women making reasonable decisions about their own lives aren’t spending much time considering the age breakdown of voters in future elections or the nation’s fiscal health in 2050. “I kind of like to have my own time,” Elizabeth Deegan, a 33-year-old living in Jersey City, told Newsweek in a phone interview. Even as a child, she says with a laugh, baby dolls “were not appealing. I always wanted the Barbies with the boyfriend and the job, not these helpless things.”

Deegan—who clerked years ago with Jordan at the Enchanted Forest, a toy store in Manhattan, and now works as a part-time delivery person for FedEx, a pet-sitter, and the founder of a community-based arts program called Project Greenville—said that for herself and other women, having a child had become an affirmative decision rather than a passive or accidental one. She was the only woman Newsweek spoke with who said she had ever been pregnant. She was 18—she can’t remember if it was just before or after graduating high school—and had an abortion.

Deegan and Jordan both stressed that they always tell prospective beaus very early on that they don’t intend to have children and cut off any budding relationships with men who feel otherwise. “You can’t be that interested in the beginning,” says Jordan, explaining why she won’t date the natally inclined. “Like what, you’re really hot or you’re really cool? There’s tons of those people out there—this is New York City.” (The man with them, on the other hand, asked after the interview that his name not be used, after realizing that his desire not to have children might not be appreciated by his partner of five years; they’d never directly discussed the topic.)

At the hookah bar, Jordan and Emily Wernet, a 25-year-old freelance illustrator of comics and tattoos, joked about the grotesqueness of a hand appearing inside a belly and about “parasites,” “popping one out,” and “horrible little grubs” in the midst of more serious conversation about their fears of relinquishing sole ownership of one’s own body.

While they bemoaned the expense and the physical and emotional effects of their birth-control regimens, they agreed it was a price worth paying to control their own fertility. “There’s a feeling like we’re basically like wombs on legs,” said another of Jordan’s former toy-store colleagues, Janet Rivera, a soft-spoken 30-year-old office manager from Brooklyn. “I feel like as a teen part of my reaction to having kids was definitely … just wanting to be seen as more than a baby factory. And then as I got older, I feel like the responsibility of having a child is a really huge deal and the expense is out of control.”

Along with kids, the group also recoiled at the domestic, often suburban lifestyle that comes with them.“Certain groups of friends have all gotten married and gone ahead and had kids and moved to Long Island because that seems to be the benchmark of success in Queens—the schools, and the pool and things that I like for weekends,” says Deegan. “It’s very orderly, like if you put them in different clothes, it could be the 1950s.”

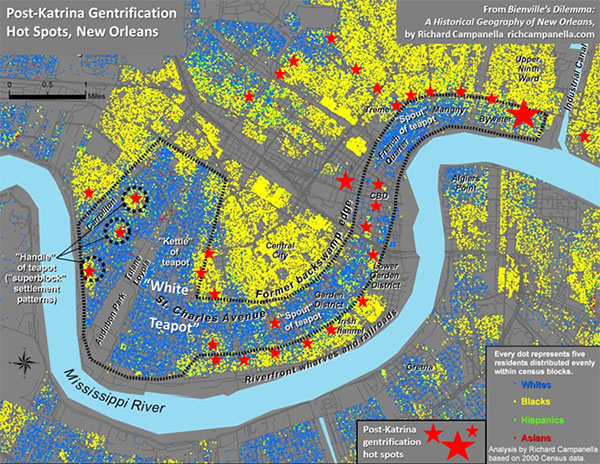

The strong correlation between childlessness and high-density city living has created essentially two Americas: child-oriented and affordable areas, and urban centers that have become increasingly expensive and child-free over the last 30 years—not coincidentally the same span over which middle-class incomes have stagnated. In Manhattan now, nearly half of all households are singletons. Over the past decade, the San Francisco, Boston, New York, Los Angeles, and Philadelphia metropolitan areas all lost children, even as lower-density and more affordable metropolitan areas such as Raleigh, North Carolina; Austin, Texas; Houston; Atlanta; Dallas–Fort Worth; and Salt Lake City registered significant gains. Seattle, once known as a strong family town, is now home to significantly more dogs than children.

Amid this shift, the childless and even the partnerless life has gained something of a cultural cachet, with some suggesting they represent not just a legitimate choice but a superior one. It’s a burgeoning movement that’s joined cultural tastemakers, academics, neo-Malthusians, greens, feminists, Democratic politicians, urban planners, and big developers. Unlike families, whose members, after all, are often stuck with one another, University of Santa Barbara psychology professor Bella De Paulo praises singles as enjoying “intentional communities” and being more likely “to think about human connectedness in a way that is far-reaching and less predictable.”

In his provocative 2012 book Going Solo: The Extraordinary Rise and Surprising Appeal of Living Alone, Eric Klinenberg writes that for the hip urban professionals who make up the so-called creative class, living alone represents a “more desirable state,” even “a sign of success and a mark of distinction, a way to gain freedom and experience the anonymity that can make city life so exhilarating.” Certainly, the number of singletons has skyrocketed: more than half of all adults today are single (a group that includes divorcées and widows and widowers), up from about one in five in 1950.

Many urban developers are placing big bets on this postfamilial demographic, while governments put money into bikeways, transit systems, art palaces, and cool residential developments that cost considerably less than schools and roads. “Singles and childless couples are the emerging household type of the future,” notes developer and urban booster Chris Leinberger. This has led to calls for creating ever-smaller apartments intended for single professionals, notes demographer Wendell Cox, an impulse that has gained the support of mayors including New York’s Michael Bloomberg.

Seeking support for their plans to build taller and smaller, urbanists like Peter Calthorpe also link their density agenda with environmentalism; he’s deemed dense urbanism “a climate-change antibiotic.” Decades after dire predictions of mass starvation and rising population growth lost credibility, the environmental mantra against children remains reflexive. Now greens are pushing for fewer high-income children, since they generate more carbon than offspring in poorer countries. Jonathon Porritt, an adviser to Prince Charles, has called for Britain to halve its population, arguing that having even two children is “irresponsible.” Lisa Hymas, senior editor at Grist, has signed up for what she calls a “fledgling child-free movement” to stand up against the “pro-natal bias that runs deep.” Her self-designation: “GINK, green inclinations, no kids.”

This trend is likely to reshape American politics in the coming decades. As the number of single women swelled by 18 percent in the last decade, they have emerged as a core constituency of the Democratic Party, a group pollster Stan Greenberg has identified as “the largest progressive voting bloc in the country” and a key part of demographer Ruy Teixeira’s “emerging Democratic majority.” That majority emerged with a vengeance in the 2012 presidential contest, as married women narrowly favored Mitt Romney, according to exit polls, while two out of three single women backed Barack Obama—and their overwhelming support accounted for the president’s margin of victory in the popular vote.

That helps explain the Obama’s campaign’s much-discussed “The Life of Julia,” a flash animation of a woman’s life over the years as marked solely by what government benefits and services she would receive from an Obama administration or be deprived of by a Romney one. This was a none-too-subtle suggestion that government can fill many of the roles, from child care to old-age care, traditionally covered by family. Conservatives assailed the pocketbook appeal (and sometimes the women who found it appealing), noting that no husband or life partner appears and that Julia’s child is referenced only twice in the span of her life, when she’s pregnant and receives free health services under health-care reform and when he later goes to a public kindergarten. After that, the child disappears.

But if singletons are swelling as a voting bloc and interest group now, the demographics of childlessness mean that they’re likely to lose out in the long term. Already, retirees have bent government to their will, with people 65 and older receiving $3 in total government spending for every dollar spent on children younger than 18 as of 2004. At the federal level (which excluded most education spending) the gap widens to 7 to 1. With an aging population, that spread will continue to expand, placing an ever-greater burden on the remaining workers and creating a disincentive for the young to have children.

In the long run, notes Eric Kaufmann, the author of Shall the Religious Inherit the Earth?, high birthrates among such conservative, religious populations as Mormons and evangelical Christians will slant our politics against the secular young, childless voting bloc as well. Even among generally liberal groups like Jews, the most religious are vastly out-birthing their secular counterparts; by some estimates roughly two in five New York Jews are Orthodox—as are three in four of the city’s Jewish children. If these trends continue, and if these children share their parents’ politics—two big ifs, to be sure—even the Democratic stronghold of Gotham will be pulled rightward.

This prospect would pose dangers to our society as a whole, and singletons in particular, including a potential reversion to a more rigidly traditionalist worldview. But perhaps most damaging would be declining markets and a hobbled economy in which governments are forced to tax the shrinking workforce to pay for the soaring retirement and health expenses of an increasingly doddering population; this is already occurring in Germany and Japan. Almost 14 million Americans are projected to have Alzheimer’s disease by 2050, according to the journal Neurology, with a cost of care that experts say could exceed $1 trillion. Less tangible may be the cultural and innovative torpidity of a country dominated by the elderly.

Of course neither outcome—the breeders multiplying their way into political power or a shrinking population, with all that would imply economically and culturally—is inevitable. There are several steps our government could take that might mitigate postfamilialism without aspiring to return to some imagined “golden age” of traditional marriage and family. These include such things as reforming the tax code to encourage marriage and children; allowing continued single-family home construction on the urban periphery and renovation of more child-friendly and moderate-density urban neighborhoods; creating extended-leave policies that encourage fathers to take more time with family, as has been modestly successfully in Scandinavia; and other actions to make having children as economically viable, and pleasant, as possible. Men, in particular, will also have to embrace a greater role in sharing child-related chores with women who, increasingly, have careers and interests of their own.

But as things stand now, the group at the hookah bar suggests where we’re going if we don’t collectively change course. “I was talking to my dad about how I don’t want to have kids,” says Jordan. “At this point, he’s resigned himself to the fact that I don’t. He’s like, ‘Tiffany, people don’t plan to have children, they just have them.’ Which is funny, because now people do plan and decide.”

We should listen carefully. In the coming decades, success will accrue to those cultures that preserve the family’s place, not as the exclusive social unit but as one that is truly indispensable. It’s a case we need to make as a society, rather than counting on nature to take its course.

This piece first appeared in The Daily Beast.

Joel Kotkin is executive editor of NewGeography.com and a distinguished presidential fellow in urban futures at Chapman University, and a member of the editorial board of the Orange County Register. He is author of The City: A Global History and The Next Hundred Million: America in 2050. His most recent study, The Rise of Postfamilialism, has been widely discussed and distributed internationally. He lives in Los Angeles, CA.

Harry Siegel is a senior politics editor for Newsweek and The Daily Beast. A former editor for The New York Sun, New York Press, and Politico and a 2010–11 Knight-Wallace Fellow at the University of Michigan, his journalism has been published in outlets including The New Republic, The New York Daily News, The New York Observer, The New York Post, The Public Interest, The Village Voice and the Weekly Standard. Email: harrysiegel@gmail.com.

Baby photo by Bigstock.