President Obama brought up Planned Parenthood three separate times at Tuesday’s town hall debate. It was an appeal aimed directly at a key part of his base: If he is reelected, it will be because of the Single Nation.

Democrats have woken up to the huge political rifts that have emerged over the past 30 years—between married and single people, and people with kids and those who don’t have them. And save African Americans, there may be no constituency more loyal to the president and his party than the growing ranks of childless and single Americans.

In the short term at least, the president and his party are seizing a huge opportunity. Since 1960, the percentage of the population that is over age 15 and unmarried increased by nearly half, 45 percent from 32 percent. Since 1976, the percentage of American women who did not have children by the time they reached their 40s doubled, to nearly 20 percent.

And even as the president has slipped in the polls, the fast-growing Single Nation has stayed behind him. Unmarried women prefer Obama by nearly 20 points (56 to 39 percent), according to Gallup, while those who are married prefer Romney by a similarly large margin.

Unmarried women (along with ethnic minorities, the poor and the workers in the public bureaucracy) are rapidly becoming a core constituency of the Democratic party, in a sense replacing the ethnic white working class.

And while single women have long been ignored (or at least not courted directly) by national politicians, Democrats are now taking direct aim—as in the Life of Julia campaign, where every milestone in her life is marked by the government benefit she’d receive under President Obama’s hubby state. Democratic strategists such as Stanley Greenberg also urge targeting singles, particularly “single women,” whom he calls “the largest progressive voting bloc in the country.”

Even among the married, children have become less of a priority. A 2007 Pew Research Center survey found that the number of adults who said that children are very important for a successful marriage had dropped by a third, from 65 percent in 1990 to 41 percent in 2010. Over that same span, financial considerations, and the willingness of a spouse to share chores and even political beliefs all became important to a greater share of adults.

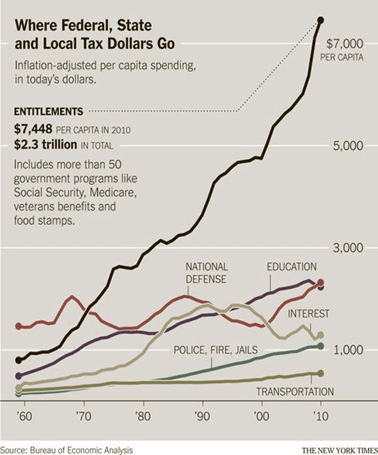

The rise in both childlessness and singlehood parallels developments already evident in other cultures, notably in East Asia and Europe. Many of these countries have experienced declining marriage and birth rates for decades. In Germany and Japan, the demographic results of this—fewer workers to support more retired people—has led to difficult tax hikes to allow the remaining young workers to maintain the funding for a growing number of aging boomers. This is the Europe’s screwed generation: “the victims of expansive welfare states and the massive structural debt charged by their parents.”

In America, by contrast, birth rates rose somewhat over the past two decades. But since the recession, the number of new children has plummeted, and it’s dropped the most precipitously for new mothers. The number of households with children today is 38 million, about the same as a decade ago, even as the total number of households has shot up by nearly 10 million.

There are now more houses with dogs than houses with children.

Singles don’t always show up at the polls, but Democratic party strategists see their numbers as simply too large to ignore, especially in close elections. Singletons almost elected John Kerry: red states had fertility rates 12 percent higher than those than blue ones.

In 2008, singles helped put Obama over the top, something widely recognized by party leaders. This summer’s surge in Obama’s ratings also derived largely from his growing appeal to single voters, and particularly women.

This reliance on single and childless voters could transform the Democratic party in the years ahead. Singlism, a term coined by psychologist Bella De Paulo, embraces the idea that far from undeserved subjects of derision or pity, the unattached represent a bridge to a more evolved humanity. De Paulo sees them as more cyber than the married set, and “more likely to be linked to members of their social networks by bonds of affection” rather than blood. Unlike families, who, after all, are often stuck with each other, singles enjoy the linkage to “intentional communities” and are thus more likely “to think about human connectedness in a way that is far-reaching and less predictable.”

A singleton approach to public policy, notes Eric Klinenberg, author of the widely celebrated Going Solo, notes, favors a high density, urban “new social environment.” This is particularly true in the central cores of social-media hubs such as Manhattan, San Francisco and, most of all, Washington D.C. In many dense urban areas now, 70 percent or more of households are childless. In contrast, the largest growth in families with children are found in places such as Dallas-Ft. Worth, Houston, Raleigh, and the Salt Lake area, which have relatively little impact on the national culture.

The new post-familial politics departs in many ways from the old urban politics. In the past, urban voters focused largely on issues concerning neighbourhood, public safety, schools, ethnic enclaves and churches. The new childless class, notes the University of Chicago’s Terry Nichols Clark, identify less with these mundane issues and more with cultural preference and aesthetics.

Clark also suggests the new singles-dominated electorate will have transcended the barriers of race and even country, embracing what he hopefully calls “a post materialist” perspective that transforms the baser considerations of those embroiled in raising children and maintaining kinship ties. No longer familial, as people have been for millennia, he predicts they could be harbingers not only of a “new race, but even a new politics.”

The emerging “new politics” of the rising Single Nation could impact elections for decades to come, particularly in Democratic strongholds like Chicago, New York or San Francisco. These areas will be increasingly dominated by a vast, often well-educated and affluent class of voters whose interests are largely defined around their own world-view, without overmuch concern with the fate of offspring, along with the urban poor and the public workers who tend to both groups. Since the childless frequently lack the kinship networks that are obliged to provide for them in moments of trouble, they tend to look more to government to care for them in hard times or old age.

But the Single Nation’s grip on power may not be sustainable for more than a generation. After all they, by definition, will have no heirs. This, notes author Eric Kauffman, hands the long-term advantage to generally more conservative family-oriented households, who often have two or more offspring. Birth rates among such conservative populations such as Mormons and evangelical Christians tend to be twice as high than those of the nonreligious.

As a result, Kauffman predicts that inevitably “the religious will inherit the earth” and ensure that conservative, more familial-oriented values inevitably prevail. Even among generally liberal groups like Jews, the orthodox and affiliated are vastly out-birthing their secular counterparts; by some estimates roughly two in five New York Jews is orthodox, including three quarters of the city’s Jewish children. If these trends continue, politics even in the progressive nirvana of Gotham may be pulled somewhat to the right.

But in the here and now, and especially this November, these long-term trends will not yet be evident. The tsunami of Chasidic and Mormon children are not yet eligible to vote, and won’t be for a decade or two. So even as the president loses among the married, the growing ranks of the Single Nation could still assure his reelection, and propel his party’s ascendency for a decade or more before the whole trend crashes against a demographic wall.

Joel Kotkin is executive editor of NewGeography.com and is a distinguished presidential fellow in urban futures at Chapman University, and contributing editor to the City Journal in New York. He is author of The City: A Global History. His newest book is The Next Hundred Million: America in 2050, released in February, 2010.

This piece originally appeared in The Daily Beast.

Barack Obama Photo by Bigstock.