After a decade of increasingly celebrated gentrification, many believe Brooklyn — the native borough of both my parents — finally has risen from the shadows that were cast when it became part of New York City over a century ago. Brooklyn has gotten “its groove back” as a “post-industrial hotspot,” the well-informed conservative writer Kay Hymowitz writes, a perception that is echoed regularly by elements of a Manhattan media that for decades would not have sullied their fingers writing about the place.

And to be sure, few parts of urban America have enjoyed a greater public facelift — at least in prominent places — than New York’s County of Kings, home to some 2.5 million people. The borough is home to four of the nation’s 25 most rapidly gentrifying ZIP codes, notes a recent Fordham study. When you get a call from the 718 area code these days, it’s as likely to be from your editor’s or investment bankers’ cell as from your grandmother.

Yet there’s a darker side to the story. This became clear to me not long ago when driving with my wife and youngest daughter to a friend’s house in the Ditmas Park section of Flatbush, one of the finest exemplars of urban renaissance in the country. We encountered a huge traffic jam on the Belt Parkway, so we exited on Linden Boulevard. For the next half hour we drove through an expanse of poverty, public housing and general destitution that hardly jibes with the “hip, cool” image Brooklyn now projects around the world.

A look at the numbers shows this was not an isolated experience. Despite the influx of hipsters and high-income sophisto professionals, Brooklyn is home to one of New York State’s poorest populations, with over one in five residents under the official poverty line, roughly 50 percent above the state average. This likely understates the problem since the cost of living in the borough is now the second-highest in the nation to Manhattan, surpassing even high-tone San Francisco.

Overall, despite some job gains, the borough’s unemployment rate stood at 11 percent this summer, up from 9.7 percent a year ago and well above the national average. Much of recent job growth has been in lower-wage industries, notes Martin Kohli, chief regional economist with the Bureau of Labor Statistics in New York City. Despite a much celebrated start-up scene, some 30,000 of the 50,000 jobs created since the recession have been in the generally low-wage health care and social assistance sector, with another 9,000 in the hospitality industry.

Poverty citywide, meanwhile, has been rising for three years running and the real Brooklyn, roughly half non-white, remains surprisingly poor. Brooklyn’s median per capita income in 2009 was just under $23,000, almost $10,000 below the national average.

So what’s going on here? Urban historian Fred Siegel, a longtime Brooklyn resident, sees a classic tale of two cities. “Brownstone and Victorian Brooklyn is booming,” he says, due in part to uncle Ben Bernanke‘s inflationary policies, which have bailed out the Wall Street banks whose profits are the bedrock of New York City’s prosperity. This money has now spread to those parts of “Manhattanized” Brooklyn closest to the core of the Big Apple, with bankers, lawyers and the like opting to settle in more human-scale neighborhoods.

But lower middle-class Brooklyn “is pockmarked with empty stores,” Siegel notes. With its once robust industrial- and port-based economy shrunken to vestigial levels, opportunities for Brooklynites who lack high-end skills or nice inheritances are shrinking. Some other areas, like Bensonhurst and Sheepshead Bay, have been revived through immigration.

Jonathan Bowles, president of the New York-based Center for an Urban Future, sees a divide between, on the one hand, “the creative class” and some immigrant neighborhoods, and on the other, “the concentrated poverty” in many other struggling areas like Brownsville (where my mother grew up) and East New York. “There are clearly huge swaths of Brooklyn where you don’t see gentrification and there won’t be anytime soon,” Bowles observes.

Part of the problem is structural. Many of Brooklyn’s working-class commuters — particularly in the eastern end of the borough — depend on a transit system designed to funnel people into the giant office clusters of Manhattan. Those left looking for work in the borough, often in low-paid service jobs, face long commutes or have to get a car, a big expense in a city with ultra-high rents, taxes and insurance costs.

Mayor Michael Bloomberg’s administration identifies itself closely with Manhattan’s “luxury city” economy. Focused on finance, media and high-end business services, this approach does not offer much to blue-collar Brooklyn. New York over the past decade has suffered among the worst erosions of its industrial base of any major metropolitan area. Brooklyn alone has lost 23,000 manufacturing jobs during that time.

Inequality in the Bloombergian “luxury city” is growing even faster than in the nation as whole. In fact, the gap between rich and poor is now the worst in a decade. New York’s wealthiest one percent earn a third of the entire city’s personal income — almost twice the proportion for the rest of the country.

So while artisanal cheese shops serve the hipsters and high-end shops thrive, one in four Brooklynites receives food stamps.

We see similar patterns across even the most vibrant of the nation’s urban regions. San Francisco gets richer with trustifarians, hedge fund managers and, for now at least, social media firms. Yet Oakland, just across the bay, suffers severe unemployment, rising crime and high vacancies. The cool bars and restaurants frequented by the creatives get the media attention, but as demographer Wendell Cox notes, roughly 80 percent of the population growth in the nation’s largest cities over the past decade consisted of people living below the poverty line.

High costs and regulatory burdens make changing this reality ever more difficult; what can be borne by Manhattan or an upscale Brooklyn neighborhood like Park Slope can devastate a grittier locale like East New York. A well-heeled banker or trust-funder may find the costs of higher taxes and regulation burdensome but still relatively trivial; such factors more strongly impact a struggling immigrant entrepreneur, or a small manufacturer, construction firm or warehouse operation. Upzonings and subsidies for real estate developers — such as those around the new Nets arena — tend to work to the benefit of high-end chains, rather than smaller, often minority-owned businesses.

Finally for all the talk, in Brooklyn and elsewhere, of a “great inversion” sending the well-to-do to cities, and what my mother would call shleppers to the suburbs, this is not the reality. Immigration and new births have supported Brooklyn’s population numbers, up 40,000 over the past decade, but as rapid outflow of Brooklynites has continued: over 460,000 more residents left than other New Yorkers or Americans moved in between 2001 and 2009, the largest loss of any borough.

These phenomena can be seen in almost every American city; anyone traveling from west Los Angeles to the east side can see the divide between the posh shops and restaurants nearer the beach and greater commercial vacancies, abandoned factories and empty offices further inland. That this is happening as well in “booming” Brooklyn is rarely acknowledged, but worth confronting. We need to learn not only how to hype “hip” cities, but think about how to restore them as aspirational places for those who aren’t members of the privileged and cool set.

Joel Kotkin is executive editor of NewGeography.com and is a distinguished presidential fellow in urban futures at Chapman University, and contributing editor to the City Journal in New York. He is author of The City: A Global History. His newest book is The Next Hundred Million: America in 2050, released in February, 2010.

This piece originally appeared in Forbes.

Brooklyn row houses photo by Bigstock.

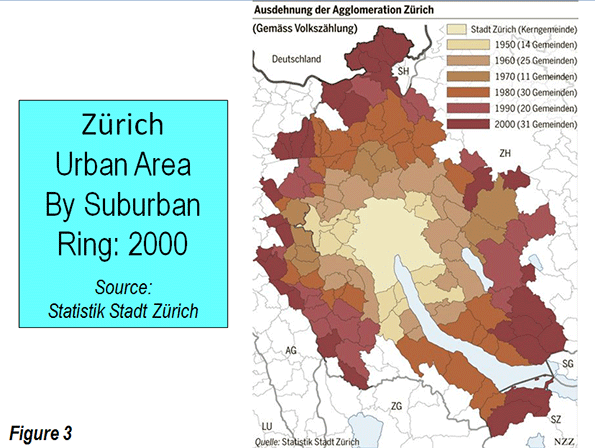

Suburbs of Zürich

Suburbs of Zürich

Zürich Railway Divide (from Hardbrücke)

Zürich Railway Divide (from Hardbrücke)