The map is shifting, and Democrats see the nation’s rapidly changing demography putting ever more states in play—Barack Obama is hoping to compete in Arizona this year, to go along with his map-changing North Carolina and Indiana wins in 2008—and eventually ensure the party’s dominance in a more diverse America, as Republicans quite literally die out.

Ruy Teixeira and others have pointed to the growing number of voters in key groups that have tilted Democratic: Hispanics, single-member households, and well-educated millennials. Speaking privately at a closed-door Palm Beach fundraiser Sunday, Mitt Romney said that polls showing Obama with a huge lead among Hispanic voters “spell doom for us.”

But, as the fine print says, past results do not guarantee future performance—and there are some surprising countervailing factors that could upset the conventional wisdom of Republican decline.

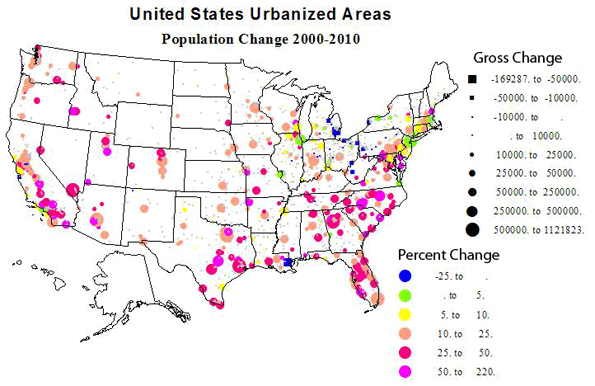

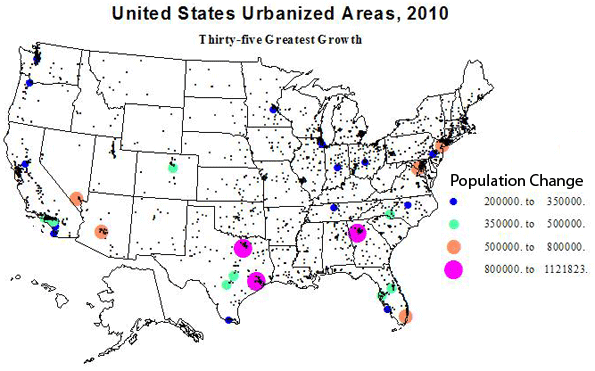

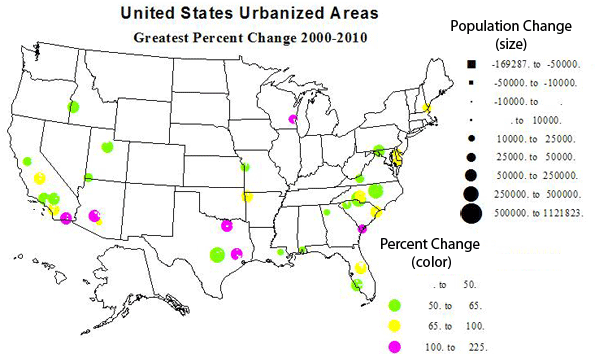

Let’s start with Hispanics. Straight-line projections suggest an ever-increasing base, as the Latino population shot up (PDF) from 35 million in 2000 to more than 50 million in 2010, accounting for half of all national population growth over the decade. Exit polls showed Democrats winning the vote in each election cycle over that stretch, with Republicans never gaining more than 40 percent of the vote. And the problem is getting worse: a recent Fox News Latino poll showed Obama trouncing Romney, 70–14, among Hispanic voters—even leading among Latinos who backed John McCain in 2008.

But longer term, Hispanic population growth is likely to slow or even recede, and Republicans are likely to do better with the group (in part because it would be hard to do much worse), as assimilation increases and immigration becomes less volatile an issue.

Rates of Hispanic immigration, particularly from Mexico, are down and are likely to continue declining. In the 1990s, 2.76 million Mexicans obtained legal permanent-resident status. That number fell by more than a million in the 2000s, to 1.7 million, according to the Department of Homeland Security. A key reason, little acknowledged by either nativists or multiculturalists, lies in the plummeting birth rate in Mexico, which is mirrored in other Latin American countries. Mexico’s birth rate has declined from 6.8 children per woman in 1970 to about 2 children per woman in 2011.

Plummeting birth rates suggest there will be fewer economic migrants from south of the border in coming decades. In the 1990s Mexico was adding about a million people annually to its labor force. By 2007 this number declined to about 800,000 annually, and it is projected to drop to 300,000 by 2030.

These changes impacted immigration well before the 2008 financial crisis. The number of Mexicans legally coming to the United States plunged from more than 1 million in 2006 to just over 400,000 in 2010, in part because of the 2008 financial crisis here. Illegal immigration has also been falling. Between 2000 and 2004, an estimated 3 million undocumented immigrants entered the country; that number fell by more than two thirds over the next five years, to under 1 million between 2005 and 2009.

Increasingly, our Latino population—almost one in five Americans between 18 and 29—will be made up of people from second- and third-generation families. Between 2000 and 2010, 7.2 million Mexican-Americans were born in the U.S., while just 4.2 million immigrated here.

This shift could spur the faster integration of Latinos into mainstream society, leaving them less distinct from other groups of voters, like the Germans or the Irish, whose ethnicity once seemed politically determinative. A solid majority of Latinos, 54 percent, consider themselves white, according to a recent Pew study, while 40 percent do not identify with any race. Most reject the umbrella term “Latino.” Equally important, those born here tend to use English as their primary language (while just 23 percent of immigrants are fluent in English, that number shoots up to 90 percent among their children).

To be sure, most Latinos these days vote Democratic. But they also tend to be somewhat culturally conservative. Almost all are at least nominally Christian, and roughly one in four is a member of an evangelical church. They also have been moving to the suburbs for the past decade or more—a trend that is of great concern to city-centric Democratic planners.

A more integrated, suburban, and predominantly English-speaking Latino community could benefit a GOP (assuming it eschews stridently nativist platform). After all, it wasn’t so long ago that upward of 40 percent of Latinos voted for the likes of George W. Bush, who won a majority of Latino Protestants.

More than race, family orientation may prove the real dividing line in American politics. Single, never-married women have emerged as one of the groups most devoted to the Democratic party, trailing only black voters, according to Gallup. Some 70 percent of single women voted Democratic in 2008, including 60 percent of white single women.

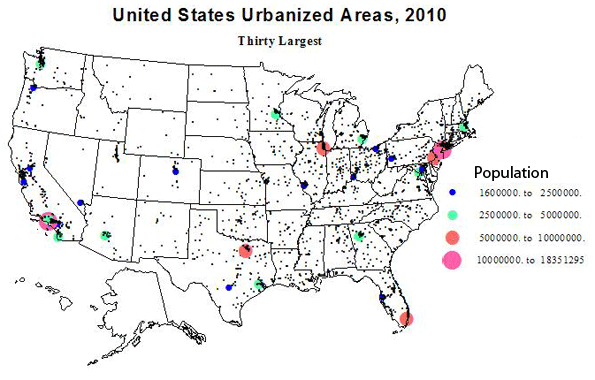

While the gender gap has been exaggerated, a chasm is emerging between traditional families, on the one hand, and singles and nontraditional families on the other. Married women, for example, still lean Republican. But Democrats dominate in places like Manhattan, where the majority of households are single, along with Washington, D.C., San Francisco, and Seattle.

In recent years Republican gains, according to Gallup, have taken place primarily among white families. Not surprisingly, Republicans generally do best where the traditional nuclear family is most common, such as in the largely suburban (and fairly affordable) expanses around Houston, Dallas, and Salt Lake City.

To be sure, Democrats can take some solace, at least in the short run, from the rise in the number of singletons. Over the past 30 years the proportion of women in their 40s who have never had children has doubled, to nearly one in five. Singles now number more than 31 million, up from 27 million in 2000—a growth rate nearly twice that of the overall population. And only one in five millennials is married, half that of their parents’ generation.

Yet as with Latino immigration, the trend toward singlehood is unlikely to continue unabated. Demographic analyst Neil Howe notes that living alone has been more pronounced among boomers (born 46–64) than millennials (born after 1980) at similar ages. Assuming marriage is delayed rather than dropped, it remains to be seen if the former singletons will maintain their liberal allegiance.

Varying birth rates also suggest that the Democrat-dominated future may be a pipe dream. Since progressives and secularists tend to have fewer children than more religiously oriented voters, who tend to vote Republican, the future America will see a greater share of people raised from fecund groups such as Mormons and Orthodox Jews. Needless to say, there won’t be as many offspring from the hip, urban singles crowd so critical to Democratic calculations.

And millennials are already more nuanced in their politics than is widely appreciated. They favor social progressivism, according to Pew, but not when it contradicts community values. Diversity is largely accepted and encouraged, but lacks the totemic significance assigned to it by boomer activists. They are environmentally sensitive but, contrary to new urbanist assertions, are more likely than their boomer parents to aspire to suburbia as their “ideal place” to live.

Some economic trends favor Republicans. Households, for example, are increasingly more dependent on self-employment, and the number relying on a government job is dropping as deficits and ballooning pension obligations force cuts in government payrolls. Republicans would do well to focus on these predominately suburban, private-sector-dependent families.

All this suggests that if they can achieve sentience, Republicans could still compete in a changing America continues changing. But first the party must move away from the hard-core nativist, authoritarian conservatism so evident in the primaries. Rather than looking backward to the 1950s, the GOP needs to reinvent itself as the party of contemporary families, including minority, mixed-race, gay, and blended ones.

This piece originally appeared in The Daily Beast.

Joel Kotkin is executive editor of NewGeography.com and is a distinguished presidential fellow in urban futures at Chapman University, and contributing editor to the City Journal in New York. He is author of The City: A Global History. His newest book is The Next Hundred Million: America in 2050, released in February, 2010.

Voter sign photo by BigStockPhoto.com.