On a Saturday afternoon at The Bund, Xiao Ming (or “Little Ming”) clings tightly onto the hands of his paternal grandparents. His maternal grandparents walk slightly ahead, clearing a path for him in the midst of all the buzz and traffic. Retracing the imprints of their imaginary footsteps, Xiao Ming takes his first tentative steps as a three year old in town for the first time. Slightly behind him, the watchful eyes and ready hands of his own parents spur him on. 1

Xiao Ming’s personal parade epitomises the popular quip in Shanghai and across China, that “it takes six adults to raise one child”. These six individuals form the unspoken support structure of China’s youth: While the OECD points out that 80% of students in Shanghai attend after-school tutoring, it fails to capture the “soft factors” behind Shanghai’s top rankings in the Program for International Student Assessment (PISA). Popular Chinese dramas such as <<房奴>> (House Slave) depict this in meticulous detail: Grandparents spend hours brewing “brain tonics” for their grandchildren, and parents pack austere work lunchboxes to save up for their child’s tuition fees.

LOW FERTILITY AND THE DEMOGRAPHIC DIVIDEND

Fifty-five years ago, China’s fertility rate was 6.1. This had fallen to 1.8 in 2010. This means that in 1955, the typical female in China would have had, on average, six children during her productive life cycle; in 2010 she would have had less than two. If Xiao Ming were born in the 1950s, he would probably have had to vie for attention and resources with at least five other siblings. Today, he has the devoted attention and care of two generations before him. Overall, the number of Chinese under 14 has declined by 6.3 percent over the last decade. (Pierson and David, 2011).

And to be sure there are short and medium term advantages to this situation. These anecdotal observations point to demographic trends that ultimately contribute to the optimal development of a nation’s trajectory. Children may be a blessing, but in many cases too many of them overburden the working population. Indeed some describe this combination of low-fertility with a large workforce as the “demographic dividend” (RAND, 2002).

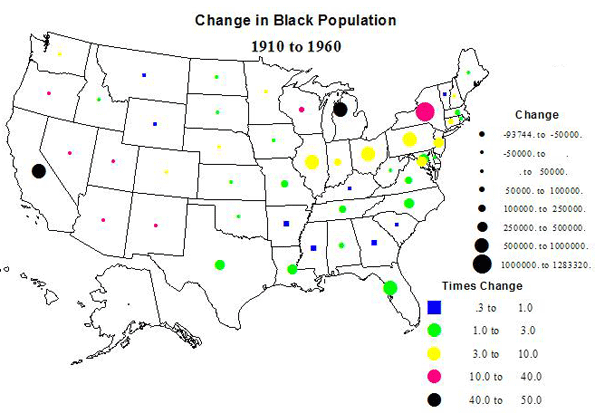

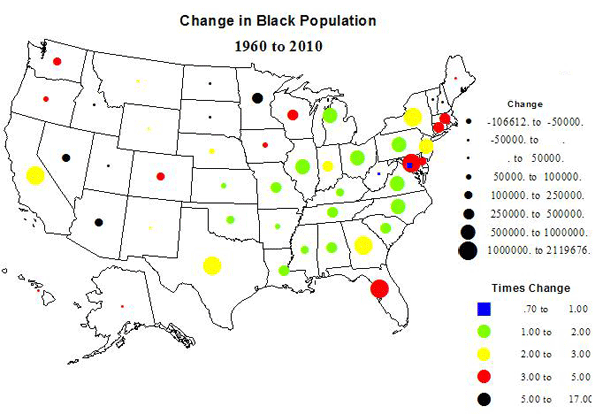

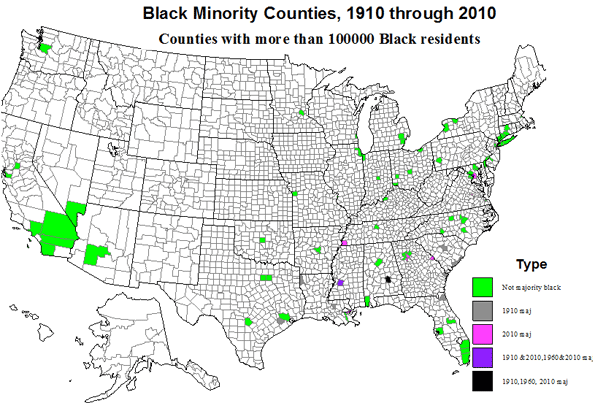

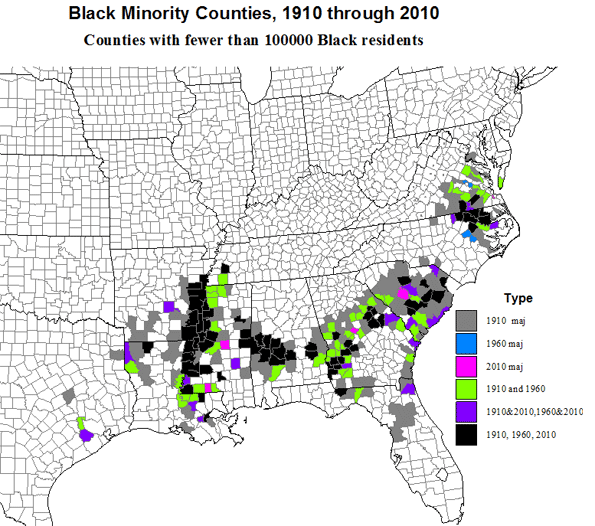

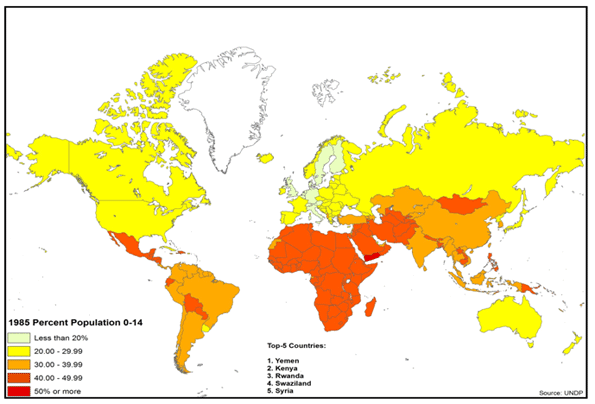

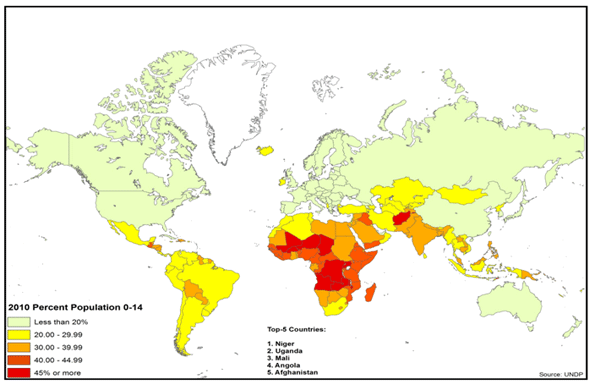

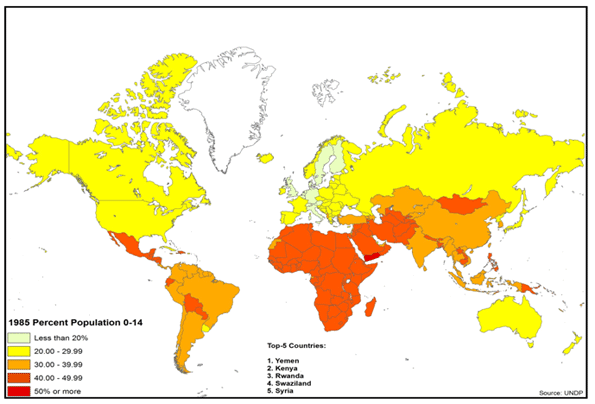

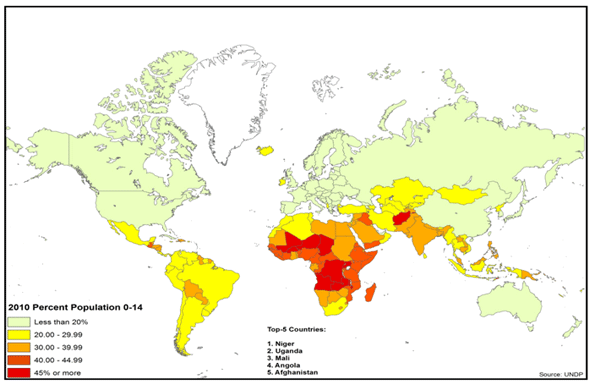

It is of little surprise that countries with a high Youth Dependency Ratios (children under 15 per 100 persons of working age, or 15 to 64) are less stable, and turn up as hotspots on the world map (Figures 1 & 2). Liberia for instance has a 5.1 percent annual natural population increase rate, 81 children per 100 of working age, and a fertility rate of 4.7. In contrast, prosperous Denmark has a 0.3 percent annual natural population increase rate, 28 children per 100 of working age and a fertility rate of 1.9 (UNDP, 2010).

|

|

|

Figure 1: Global Youth Dependency Ratio (1985)

|

|

|

|

Figure 2: Global Youth Dependency Ratio (2010)

|

As population increases outpace economic opportunities and growth, nations at risk fail to accommodate new entrants into the workforce. In addition, caring for children requires a high proportion of resources, thus depressing the rate of economic growth. (Bloom et.al., 2001).

A low median age is thus a harbinger of impending stresses, where in extreme cases at least 50% of the population is below 20 years of age (UNDP, 2010). In comparison, the median age of the developed world averages 30 – 40 years. This forms the foundational basis of several youth bulge studies of late, explaining demographic factors behind the Arab Spring (Anderson, 2011), that was in part driven by massive increase in youth (Hvistendahl, 2011; Fuller, 2003) and the youth workforce (Kuhn and Korbel, 2011; Schwartz, 2011), much of whom are unemployed and underemployed (Bajora, 2011).

THE FERTILITY IMPLOSION

Yet there is a distinct disadvantage as well to ever lower birthrates. Globally population growth rates are likely to continue dropping – to less than 0.8 percent worldwide by 2025 – largely due to an unanticipated drop in birthrates in developing countries such as Mexico and Iran. These declines are in part the result of increased urbanization, the education of women, and higher property prices. Already the global fertility rate, including the developing countries, has dropped in half to an estimated 2.5 today (Longman, 2010a). Close to half the world’s population lives, notes demographer Nicholas Eberstadt, in countries with below replacement rate birth-rates. The world, he suggests, is experiencing a “fertility implosion” (Eberstadt, 2010).

Like a population explosion, a demographic implosion has consequences. Countries that have previously engineered reductions in the fertility rates – Singapore (Yap, 2003), Hong Kong (FPAHK, 2011), Vietnam (Bennett-Jones, 2000), India (WHO, 2011) and Indonesia (Hull, 2007) – have done so to achieve more manageable economic conditions. Similar initiatives are being debated, even in the in the Philippines (Pernia et. al., 2011), where religious interpretations are being contested. China’s “one child policy” represented just a more authoritarian expression of a widespread global process. Yet this process often includes many unintended and potentially damaging consequences. However, elsewhere, virtually the same results were replicated without government policy direction, such as in Brazil (Gomey, 2011).

Chinese “fertility implosion” is already having profound impact on marriage in China. Today researchers characterize declining fertility in China into “waves of singletons” (单身潮). While the first three, distinct “waves” or phases since 1950 are well established (王霞, 2006),it has recently been noted that the fourth (第四次单身潮) is currently in progress(陈亚亚, 2011). In the fourth and current wave, women increasingly view child-bearing and marriage as a form of entrapment and a burden that can interfere with aspirations of affluence (杨燕明 2011; 黄蓉芳 and 杨励潮, 2011).

Not surprisingly this is most evident in the advanced urbanized parts of China, such as Shanghai, where there are already three million people over 60, or 2l percent of the population, roughly equal to the share in many advanced countries (McCartney, 2009).

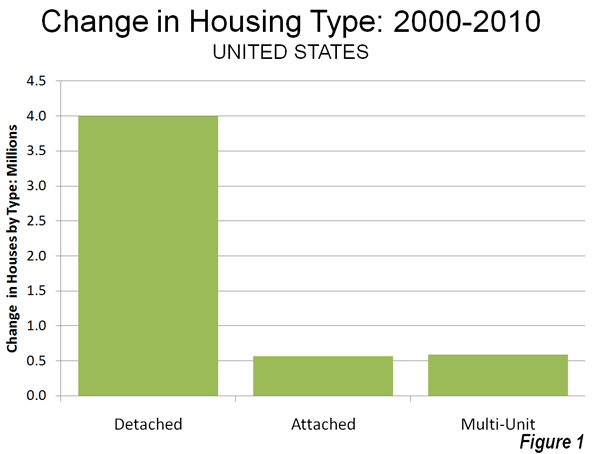

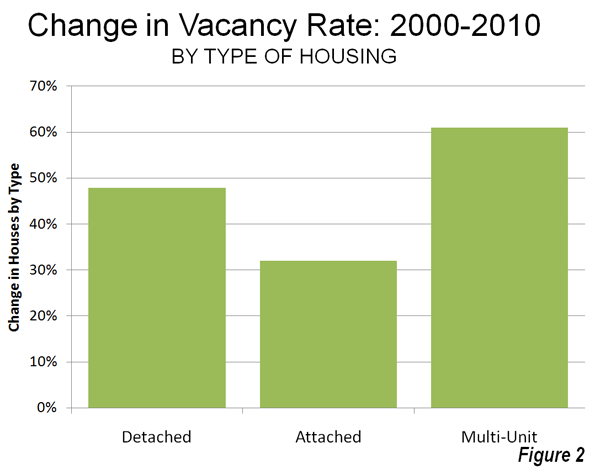

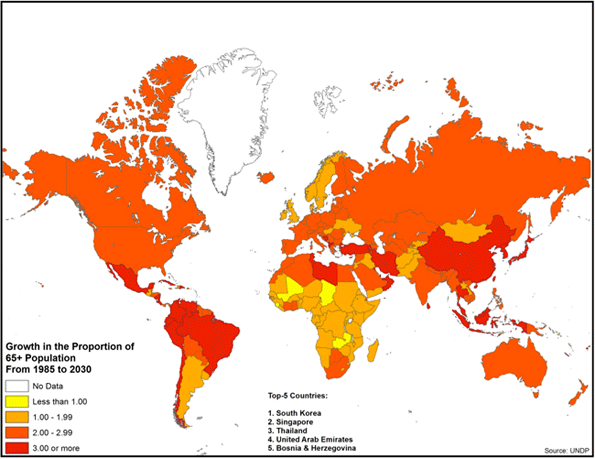

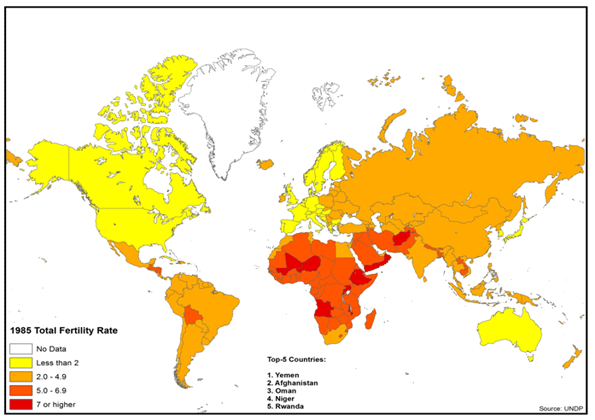

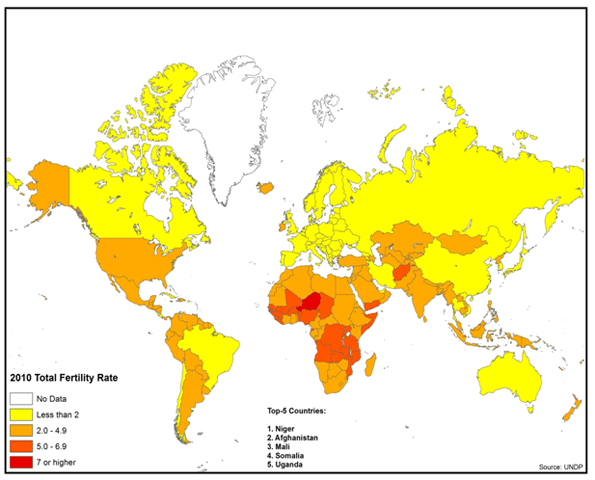

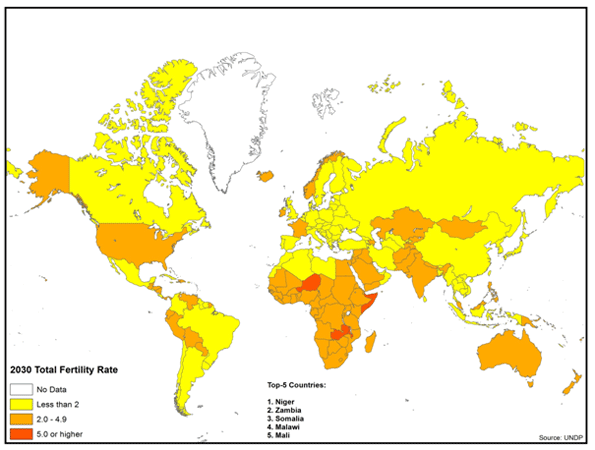

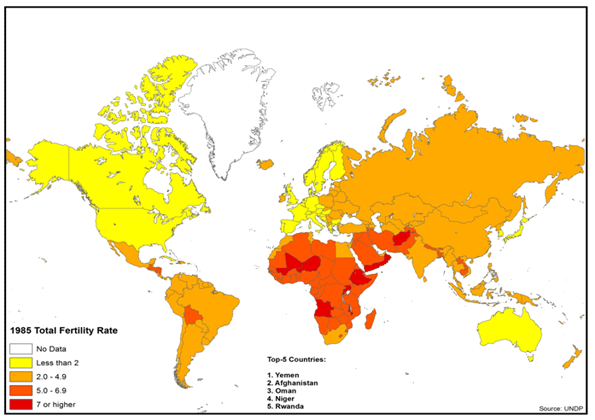

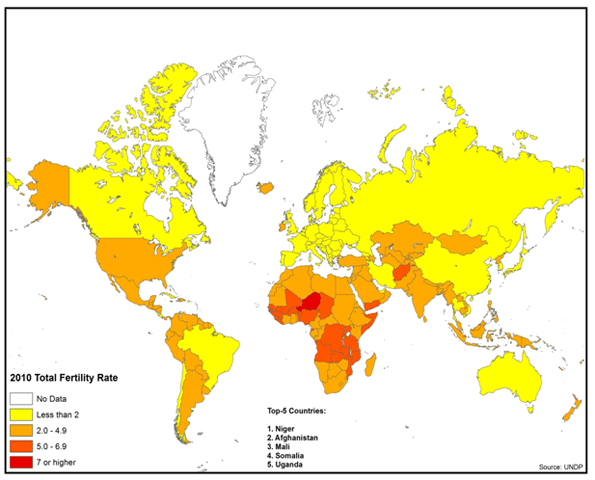

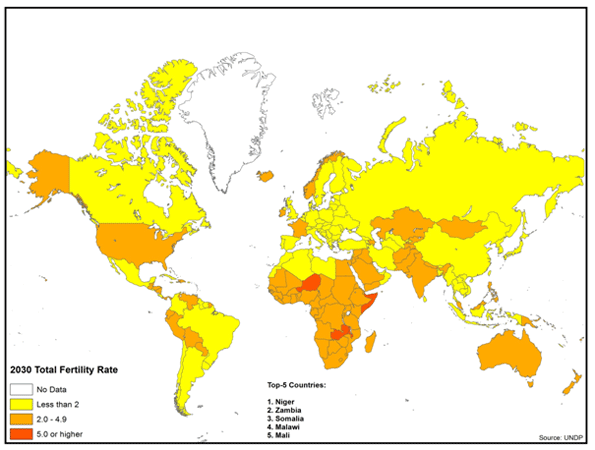

China now has a fertility rate of 1.6, below that of Western Europe. Nor is China alone. Other middle income nations and even low income nations are experiencing significant declines in fertility rates. Brazil and Iran already have fertility rates less than that of the United States. In Bangladesh and Indonesia, fertility rates are projected to drop below replacement rates (2.1) by 2030. Around the world, increasing affluence has been associated with fewer children, as is indicated in Figures 1 – 3. The longer run implications of these less than replacement fertility rates (2.1) is smaller and much older populations (Figures 3, 4 &5).

|

|

|

Figure 3: Global Total Fertility Rate (1985)

|

|

|

|

Figure 4: Global Total Fertility Rate (2010)

|

|

|

|

Figure 5: Global Total Fertility Rate (2030)

|

GRAYING OF THE WORLD

Here’s the big issue down the historical road: Thirty years from now, how will Xiao Ming handle six elderly parents and grandparents, all by himself? Xiao Ming’s impending dilemma is not unique to China.

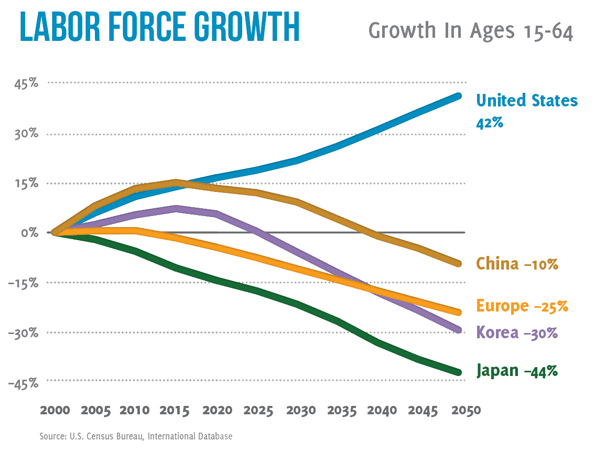

Overall what author Phil Longman calls a “gray tsunami” will be sweeping the planet, with more than half of all of population growth coming from people over 60 while only six percent will be from people under 30. The battle of the future – including in the developing world – will be, in large part, how to maintain large enough workforces required for the economic growth needed to, among other things, take care of and feed the elderly (Longman, 2011b). The National Bureau of Research (NBER) further notes that similar to child dependents, a large elderly population similarly requires a large proportion of resources, which likewise can inhibit economic growth (Bloom et. al., 2001).

Right now the situation seems dire. Fertility rates are projected to continue their decline. Increasing life expectancy is contributing to a substantial increase in the elderly population. In many nations, the size of the elderly population will exceed that of the under 15 population for the first time.

This could not have happened at a worse time, because the elderly have become ever more dependent on the state in many nations. Supporting a larger elderly population requires a larger work force, however it will be smaller.

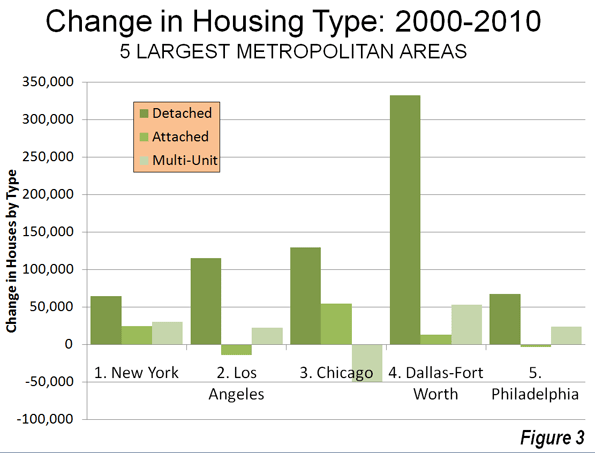

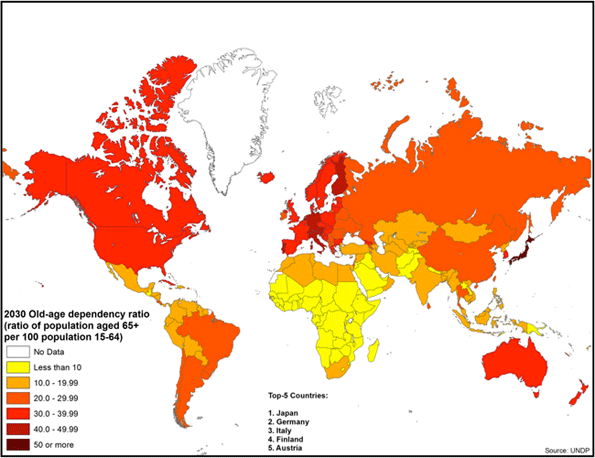

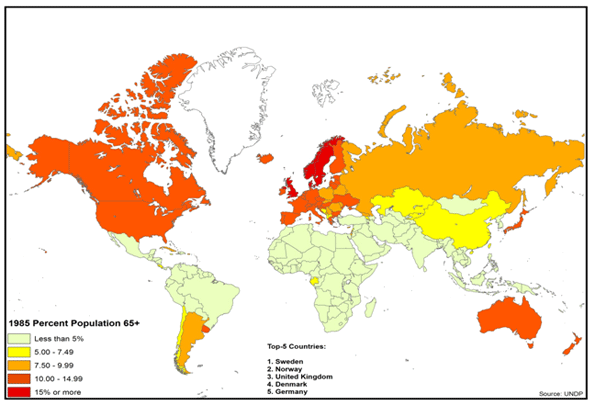

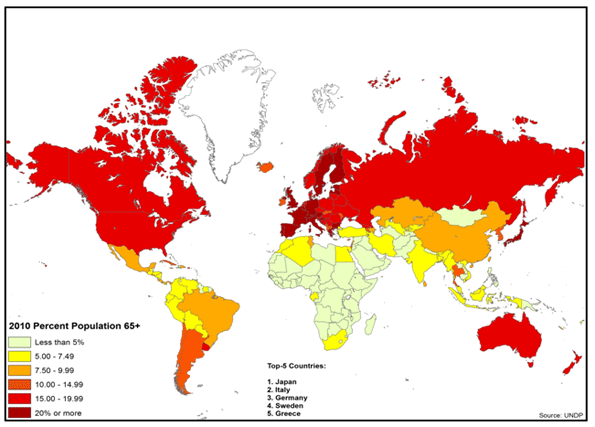

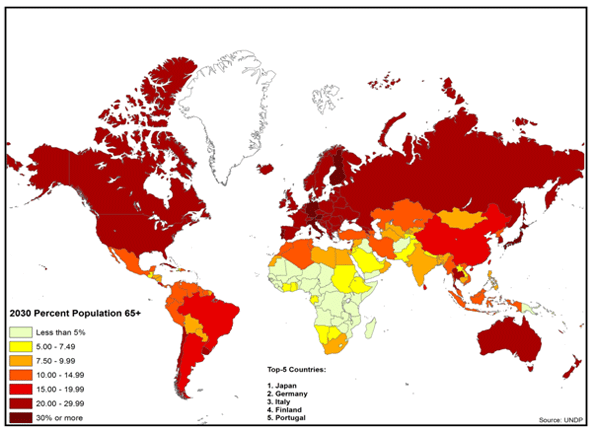

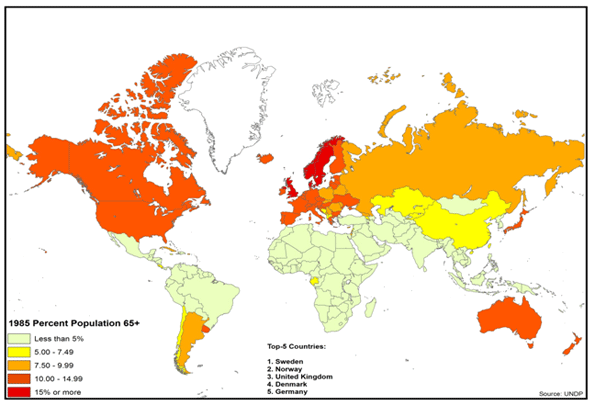

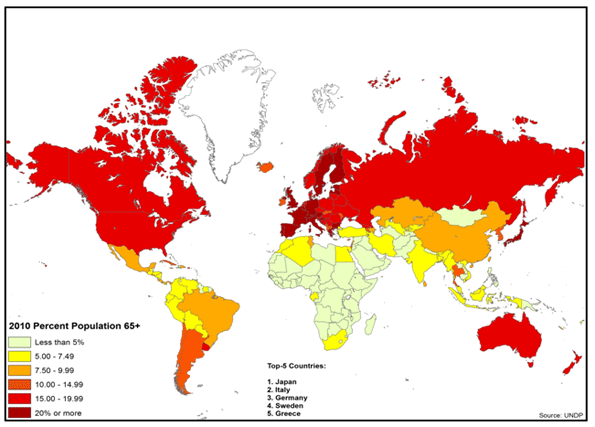

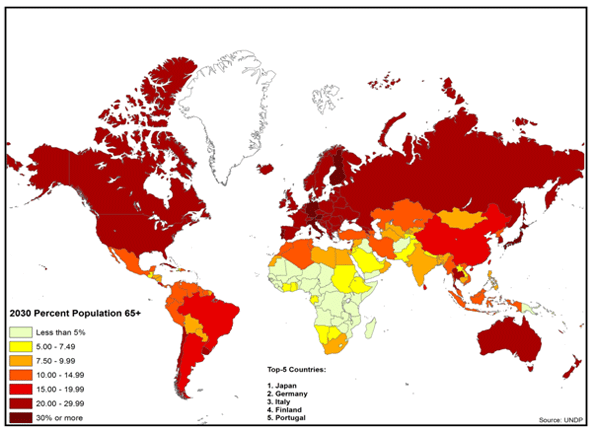

All of this leads to a demographic future that promises to challenge the nations of the world as never before. This is illustrated by rising Old Age Dependency Ratios in Figures 6, 7 & 8.

|

|

|

Figure 6: Global Old Age Dependency Ratios (1985)

|

|

|

|

Figure 7: Global Old Age Dependency Ratios (2010)

|

|

|

|

Figure 8: Global Old Age Dependency Ratios (2030)

|

High income countries are projected to experience elderly population increases on the order of 60 percent in relation to the working age population (15 – 64) by 2030. In the United States, there are now 20 people 65 or over for every 100 of working age; little changed since 1985, when it was 18. However, by 2030 there will be 33 seniors per 100 working people. More extreme will be the fates of the world’s third and fourth largest economies. Germany’s ratio of elderly to working age individuals is already 33, compared to 21 in 1985. In 2030 this ratio will rise to an almost unimaginable 48, meaning that there will be only two working people per retiree. Japan’s situation is even worse. As recently as 1985, Japan had a relatively healthy 15 retirees for every working age person. Today this ratio is one the world’s most extreme: with 35 seniors per 100 working age people. In 2030, this ratio is expected to rise to 53.

Things will be a bit better, at least in the next two decades, in middle income countries such as China and Brazil. But the rate of aging will be even greater than in the high income nations. Both China and Brazil will experience a doubling of their Old Age Dependency Ratios; both will rise slightly above current US levels by 2030. China is projected to rise from 11 to 23, while Brazil’s will increase from 10 to 20. Despite its theological regime, which might be seen as working against smaller families, middle-income Iran is also aging rapidly. It should see a doubling of its Old Age Dependency Ratio, but from a low 7 to a manageable 14.

There will be a mix of results in the lower income countries, as illustrated by the Philippines and Nigeria. In the Philippines, the fertility rate is expected to remain high by current global standards, at 2.6 in 2030, only a modest drop from the present 2.9. However, the elderly will increase 60 percent relative to the working age population (from an Old Age Dependency Ratio of 6 to 10 in 2030). Similarly, in Nigeria the fertility rate is expected to decline only slightly, from 4.8 to 4.5. Alone among the group of nations reviewed, Nigeria is expected to experience only a negligible increase in the Old Age Dependency Ratio, remaining at 6. In 1985, these nations had Old Age Dependency Ratios of between 5 to 7 (UNDP, 2010).

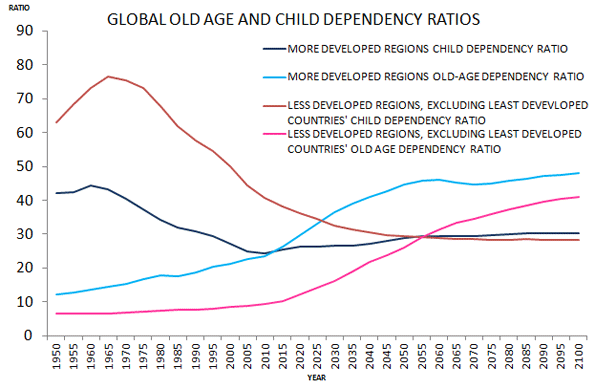

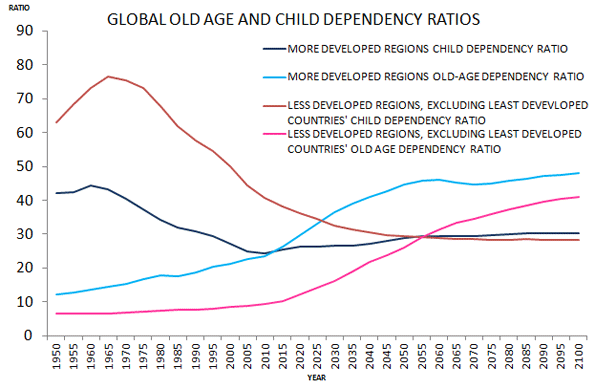

Even if we were to discount population projections going forward (Shahani, 2011), the world is on the verge of a global demographic precipice (Figure 9) – one in which the the increase in proportion of elderly far outweighs that of the increase in proportion of children. A world which Andrew Blechman terms, “a world without children” (Blechman, 2009), and that Ted Fishman describes as one which “pits young against old, child against parent, worker against boss, company against rival, and nation against nation” (Fishman, 2009).

|

|

|

Figure 9: UNDP global old age and child dependency ratios. In the developed world, child dependency will equal old-age dependency within the next 5 years. In the developing world this will happen in the next 40 years.

|

FINANCING THE UNFINANCABLE?

Where there is Virtually Universal State Support.The options available for addressing increasing old age dependency are not very attractive. Older people require considerably more in terms of overall support, particularly for health care, than younger generations (Feinberg et. al., 2011). This is a crisis particularly in demographically declining countries with well-developed social welfare nets. A recent Bank of International Settlements study found that, due to these pressures, Germany’s ratio of public debt to gross domestic product could exceed 200 percent in 2030, with annual debt service approach 10% of GDP. This would be a fiscal burden twice that of Greece today (Eberstadt and Hans, 2010).

Where there is Less State Support: In many nations, state retirement systems often fail to cover a large share of the elderly population. While arrangements vary widely, many elderly must find their own ways to survive, such as by working longer or by relying on families. As emerging nations consider establishing or expanding social safety nets for the elderly, they need to consider the experience of the high-income world welfare states.

Family Support: Given the stresses on public systems, it might be hoped that the elderly could be supported by their children. But this solution has been losing hold throughout the developed world. The mathematics cannot work in any of the challenged nations, at whatever income level: As the elderly population increases relative to the working population, an adult Xiao Ming is unlikely to be able, or willing, to support six parents or grandparents or even two or three.

Reduce Benefits? The accounting answer may be simple – limit elderly benefits to what society can afford. But the politics do not work. Concentrated, organized interests, such as the elderly who receive state benefits, are likely to block any such reforms. The difficulty of dealing with today’s challenges, which are modest compared to the future, is illustrated by recent developments in Western Europe and the United States, where recipients of state aid have fought, often successfully, to retain their benefits even in the face of significant funding challenges.

Increase the Birth Rate? A substantial increase in the birth rate in low fertility nations could help, but it would need to happen immediately. This would require broad acceptance of earlier and more frequent child-bearing women, many of whom are increasingly finding a life of affluence to be preferable to one of child-raising. Some projections show increases in the fertility rate in future years, however it could be too little-too late (UNDP HDI, 2010).

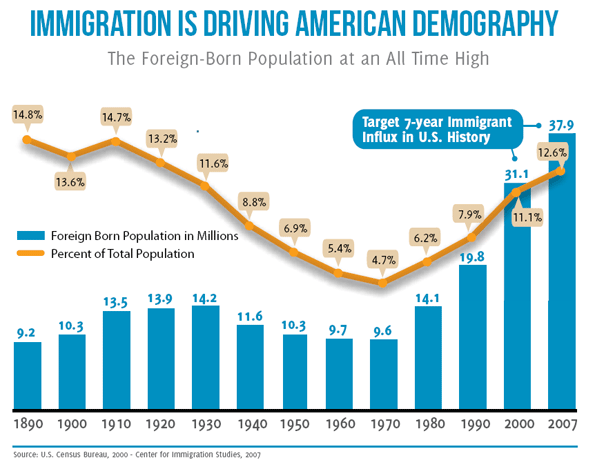

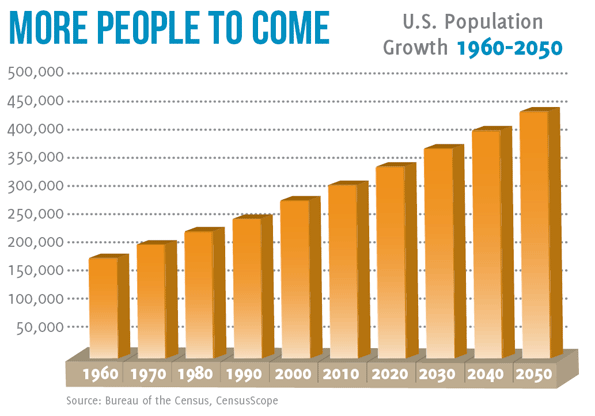

More Migration? Increased migration from poorer countries could help richer countries finance the needs of their elderly. However, migration rates are dropping even in the United States, which is by far the world’s largest country for immigration. Although the US foreign born population grew by 10 million over the past decade, both illegal and legal immigration have been dropping. In 2008 there were over one million naturalizations; last year there were barely 600,000, a remarkable 40% drop (Ohlemacher, 2006).

Working Longer: As life expectancy has increased in recent decades, retirement ages have changed little. For example, in the United States, since the establishment of the state retirement system, life expectancy at birth has increased 16 years, while the retirement age has increased only two years. Generally, every additional year in life expectancy is an additional year of state support. One possible solution would be to extend retirement ages beyond the 65 years common in the high income world. Yet while life expectancy has increased, perhaps in 2030, the standard Old Age Development Ratio should be calculated using the population that is more than 75 years old instead of 65.

More Women in the Work Force: Another factor that could assist in meeting the daunting financial challenge of supporting the elderly would be for an increase in female participation in the workplace. The extent to which such an expansion is theoretically possible varies significantly by nation, but this could be part of the solution. There is an important caveat, however. Increasing the supply of workers does not automatically create wealth. Western Europe has had intractable unemployment rates for decades and has been joined in recent years by the United States. More workers, of either sex, will require strong enough economic growth to generate sufficiently high paid employment.

Affordable Housing:One reason for lower birthrates may be the cost of housing. Many of the countries, and regions, with the most expensive housing also tend to experience the lowest fertility – Taiwan, Singapore, Hong Kong, and much of Western Europe. Across China, for example, it is generally agreed that apartment sales prices are exceedingly high relative to incomes (Pierson, 2011). In a number of places with considerable land for new development, like the United Kingdom, Australia and some metropolitan areas of the United States and Canada, researchers have connected substantially increasing prices and housing shortages with overly-restrictive land use regulation. Any strategy that would encourage greater fertility might need to address this issue. Further, the artificially higher house prices consume discretionary income that could be better put to encouraging economic growth by increasing the demand for other goods and services.

Economic Growth: Economic growth represents the best hope. Chinese-level GDP increases would better position to countries for demographic challenges than the Japanese or European rates of the last two decades. Clearly, economic expansion would ameliorate the pre-occupation with splitting the economic pie. It will also be important to pursue policies that minimize costs for households. If, for example, the cost of housing or food is less, more money will be available for necessary social programs (and there will be less resistance to funding them). In a sense, the difference between laggard and strong economic growth can make a huge difference. For example, economist Bret Swanson has shown that the United States could conquer its well-publicized debt burden with economic growth rates of 4 percent (Swanson, 2011).

This Issue Must be Addressed: No one can accurately predict the future, but it is necessary to focus on the issue of aging and declining fertility. In advanced countries, if the elderly retain their state benefits and economic growth continues to be modest or even stagnant, the pressure on economies will be severe. There will be, to put it simply, less money to go around. Those who primarily fund the state – the working population – will have to pay more and could see material reductions to their standards of living. Central Bankers could yield to the temptation to print enough money to seemingly hyper-inflate away the problem, but that could lead to a lower standard of living for all.

Overall our research suggests several possible solutions, including extending work and careers into the 70s; means tested benefits; greater incentives for having children; and measures to keep housing more affordable and family friendly wherever possible. But the ultimate issue will be maintaining economic growth.

The future of Xiao Ming and billions more will depend upon the result.

Emma Chen is a Senior Strategist at the Centre for Strategic Futures, Singapore. The views expressed within this article are solely her own. Publication does not constitute an endorsement by the Centre for Strategic Futures, Singapore.

Wendell Cox is a consultant specializing in demographics and urban issues, principal of Demographia and a visiting professor at the Conservatoire National des Arts et Metiers in Paris.

This project was supported by the Legatum Institute. Maps designed by Ali Modarres, chairman, Geography Department, California State University, Los Angeles.

REFERENCES

王霞. 2006. “第三次单身潮解析 (Analysis of Youth Single Phenomenon in the Third Bachelor Trend).”中国青年研究(China Youth Study) 2006(12).

杨燕明. 2011. “大家谈中国:第四次单身潮反映家庭婚姻危机 (Everybody Discusses China: Fourth Wave of Singles Reflects Family and Marriage Crises).” BBC News. Accessed September 19, 2011.

http://www.bbc.co.uk/zhongwen/simp/comments_on_china/2011/07/110720_coc_marriage_byyangminyan.shtml.

陈亚亚. 2011. “都市单身女性的生存状态考察 (Observations on the living status of urban single females).” 华人社会和谐家庭论坛暨第九届全国家庭问题学术研讨会(The Ninth National Conference on Family Issues, The Forum for Chinese Societal Harmony and Family), hosted in Guang Dong, 2011.

黄蓉芳 and 杨励潮. 2011. “中国将迎第四次单身潮 近4%的女性因性取向单身 (China Will Meet its Fourth Wave of Singles – Nearly Four Percent of Females are Single Due to Sexual Orientation).” Xinhua, July 19.

Anderson, Lisa. 2011. “Demystifying the Arab Spring.” Foreign Affairs May/June 2011 2-7.

Bajoria, Jayshree. 2011. “Demographics of Arab Protests.” Council on Foreign Relations. Accessed September 19, 2011. http://www.cfr.org/egypt/demographics-arab-protests/p24096.

Bennett-Jones, Owen. 2000. “Vietnam’s Two-Child Policy.” BBC News. Accessed September 19, 2011. http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/asia-pacific/1011799.stm.

Blechman, Andrew D. 2009. Leisureville: Adventures in a World Without Children. New York: Grove Press.

Bloom, David E., David Canning, and Jaypee Sevilla. 2001. “Economic Growth and the Demographic Transition.” NBER Working Paper Series. Accessed September 19, 2011. http://www.nber.org/papers/w8685.pdf.

Eberstadt, Nicholas, and Hans Groth. 2010, “Time for Demographic Stress Test.” Wall Street Journal, November 27.

Eberstadt, Nicholas. 2010. “The Demographic Future.” Foreign Affairs 89:54-64.

Feinberg, Lynn, Susan C. Reinhard, Ari Houser, and Rita Choula. 2011. “Valuing the Invaluable: 2011 Update – The Growing Contributions and Costs of Family Caregiving.” AARP Public Policy Institute. Accessed September 9, 2011. http://assets.aarp.org/rgcenter/ppi/ltc/i51-caregiving.pdf.

Fishman, Ted. 2010. Shock of Gray. New York: Scribner

Friedman, Benjamin. 2005. The Moral Consequences of Economic Growth. New York: Alfred A. Knopf.

Fuller, Graham E. 2003. “The Youth Factor: The New Demographics of the Middle East and the Implications for U.S. Policy”. Brookings Institute. Accessed September 19, 2011.

http://www.brookings.edu/~/media/Files/rc/papers/2003/06middleeast_fuller/fuller20030601.pdf.

Gorney, Cynthia. 2011. “Brazil’s Girl Power.” National Geographic, September.

Hvistendahl, M. 2011. “Young and Restless can be a Volatile Mix.” Science 333:552-4.

Hull, Terence H, “Formative Years of Family Planning in Indonesia,” in The Global Family Planning Revolution: Three Decades of Population Policies, edited by Warren C. Robinson and John C. Warren (Washington: The World Bank, 2007), 246.

Kuhn, Randall, and Josef Korbel. 2011. “On the Role of Human Capability in the Arab Spring.” Working paper, University of Colorado Boulder. Accessed September 19, 2011. http://www.colorado.edu/ibs/pubs/pop/pop2011-0011.pdf.

Longman, Phillip. 2010. “Think Again: Global Aging.” Foreign Policy. Accessed September 19, 2011. http://www.foreignpolicy.com/articles/2010/10/11/think_again_global_aging.

Longman, Phillip. 2011. “The World Will be More Crowded – With Old People.” Foreign Policy. Accessed September 19, 2011. http://www.foreignpolicy.com/articles/2011/08/15/the_world_will_be_more_crowded_with_old_people.

McCartney, Jean. 2009. “China Steps Back from One Child Policy.” Times, July 24.

Ohlemacher, Stephen. 2006. “3M a Year Leave Developing Countries.” Associated Press, August 17.

Pernia, Ernesto M., Stella Alabastro-Quimbo, Maria Joy V. Abrenica, Ruperto P. Alonzo, Agustin L. Arcenas, Arsenio M. Balisacan, Dante B. Canlas, Joseph J. Capuno, Ramon L. Clarete, Rolando A. Danao, Emmanuel S. de

Dios, Aleli dela Paz-Kraft, Benjamin E. Diokno, Emmanuel F. Esguerra, Raul V. Fabella, Maria Socorro Gochoco-Bautista, Teresa J. Ho, Dennis Claire S. Mapa, Felipe M. Medalla, Maria Nimfa F. Mendoza, Solita C. Monsod, Toby Melissa C. Monsod, Fidelina Natividad-Carlos, Cayetano W. Paderanga, Gerardo P. Sicat, Orville C. Solon, and Edita A. Tan. 2011. Discussion paper, University of the Philippines. Accessed September 19, 2011. http://www.econ.upd.edu.ph/dp/index.php/dp/article/viewFile/670/132.

Pierson, David. 2011. “In China, Having Children is no Longer a Given.” Los Angeles Times, September 2.

RAND Corporation. 2002. “Banking the ‘Demographic Dividend’.” Accessed September 19, 2011. http://www.rand.org/pubs/research_briefs/RB5065/index1.html.

Shahani, Lila Ramos. 2011. “Whither the RH Bill”. BusinessWorld Online. Accessed 19 September, 2011. http://www.bworldonline.com/content.php?section=Opinion&title=Whither-the-RH-bill?&id=38459

Schwartz, Stephanie. 2011. “Youth and the ‘Arab Spring’.” United States Institute of Peace. Accessed September 19, 2011. http://www.usip.org/publications/youth-and-the-arab-spring.

Swanson, Bret. 2011. “The Growth Imperative.” Presentation to the National Chamber Foundation, Washington D.C., May 24. Accessed September 19, 2011. http://entropyeconomics.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/05/EE-NCF-Growth-Imperative-05.24.11-v1.9.pdf.

The Family Planning Association of Hong Kong. 2011. “Family Planning Milestone.” Accessed September 19, 2011. http://www.famplan.org.hk/fpahk/en/template1.asp?style=template1.asp&content=about/history.asp.

United Nations Development Programme. 2010. “International Human Development Indicators.” New York: UN Human Development Report Office. Accessed September 19, 2011. http://hdr.undp.org/en/statistics.

U.S. Department of Homeland Security. 2010. “Table 20 – Petitions for Naturalization Filed, Persons Naturalized, and Petitions for Naturalization Denied: Fiscal Years 1907 to 2010.” Washington D.C.: U.S. Department of Homeland Security. Accessed September 19, 2011. http://www.dhs.gov/files/statistics/publications/YrBk10Na.shtm.

United Nations Development Programme. 2010. “International Human Development Indicators.” New York: UN Human Development Report Office. Accessed September 19, 2011. http://hdr.undp.org/en/statistics.

United Nations Development Programme. 2010. “International Human Development Indicators.” New York: UN Human Development Report Office. Accessed September 19, 2011. http://hdr.undp.org/en/statistics.

United Nations Development Programme. 2010. “International Human Development Indicators.” New York: UN Human Development Report Office. Accessed September 19, 2011. http://hdr.undp.org/en/statistics.

World Health Organization Regional Office for South-East Asia. “India and Family Planning: An Overview.” Accessed September 19, 2011. http://www.searo.who.int/LinkFiles/Family_Planning_Fact_Sheets_india.pdf

Yap, Mui Teng. 2003. “Fertility and Population Policy: The Singapore Experience.” Journal of Population and Social Security (Population) 1:643-58.

1: Based on personal history of a co-author