In recent years, homeowners have been made to feel a bit like villains rather than the victims of hard times, Wall Street shenanigans and inept regulators. Instead of being praised for braving the elements, suburban homeowners have been made to feel responsible for everything from the Great Recession to obesity to global warming.

In California, the assault on the house has gained official sanction. Once the heartland of the American dream, the Golden State has begun implementing new planning laws designed to combat global warming. These draconian measures could lead to a ban on the construction of private residences, particularly on the suburban fringe. The new legislation’s goal is to cram future generations of Californians into multi-family apartment buildings, turning them from car-driving suburbanites into strap-hanging urbanistas.

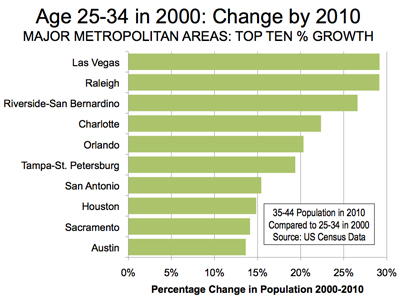

That’s not what Californians want: Some 71% of adults in the state cite a preference for single-family houses. Furthermore, the vast majority of growth over the past decade has taken place not in high-density urban centers but in lower-density peripheral areas such as Riverside-San Bernardino. Yet popular preferences mean little in a state where environmental zealotry increasingly dictates how people should live their lives.

Some advocates do cite market forces to justify their policies. Economists on the left and right have cited the recent housing bust as proof that homes are not great investments, suggesting people would be better off leaving their money to the tender mercies of Wall Street speculators. Some demographers also suggest that young people will choose to live in high-density regions throughout their lives and that as boomers age they too will opt out of suburbs for urban apartment living.

These “facts” may be more grounded in academic mythology than reality. Some widely quoted experts, like the Anderson Forecast at UCLA, cite Census information to say that demographics are shifting demand from single-family homes to condos and apartments, although the Census asked no such question. These experts also fail to address why condo prices have dropped even more in the major California markets than single-family home prices; the percentage of starts that come from single-family houses shifts from year to year, but last year’s number tracks around the same level as seen in the 1980s.

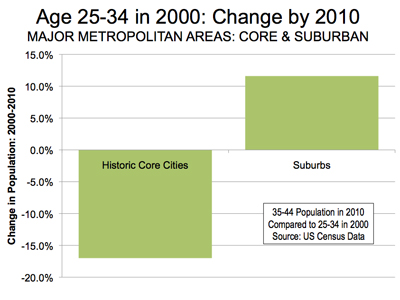

Perhaps the biggest weakness in the analysis lies with long-term demographic factors. As I wrote last week, many of the “young and restless” folks whom city planners try to court tend to move into suburbs and affordable low-density regions as they grow older and begin starting families. Similarly, the vast majority of boomers, according to AARP, want to remain in their old homes as long as possible. Most of those homes are located in suburban, low- to medium-density neighborhoods.

But who needs facts when you have religion? Take the Association of Bay Area Governments (ABAG) and Metropolitan Transit Commission’s (MTC) new “sustainable communities strategy,” a document designed to meet the requirements of the state’s draconian anti-greenhouse gas legislation.

This “strategy” seeks to all but reduce growth in the region’s lower-density outer fringe – eastern Contra Costa County as well as the Napa, Vallejo and Santa Rosa metropolitan areas — which grew more than twice as fast as the core and inner suburbs. Instead the ABAG-MTC projects a soaring increase in demand for high-density housing and its latest “vision” report calls for 97% of all the region’s future housing be built in urban areas, virtually all of it multi-family apartments, to accommodate an estimated 2 million residents

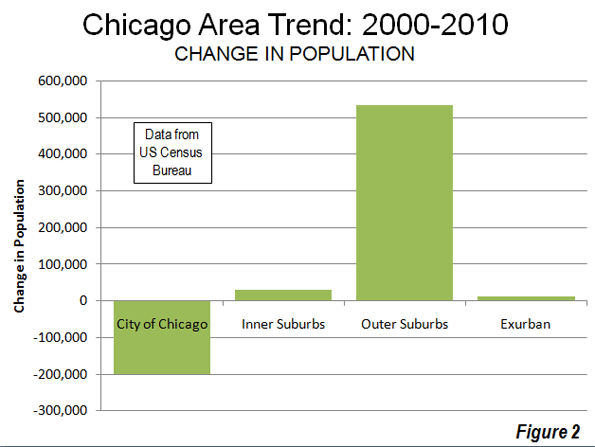

The projections underpinning ABAG’s strategy are absurd. Over the past decade the population of the region’s historic core cites San Francisco and Oakland — where much of the dense growth would be expected to take place — increased by 1.7%, compared with 6.5% for the suburbs. Overall regional growth stood at a modest 5.1%, roughly half that of the previous decade and just about half of the national and state averages.

Given this record, a more reasonable assumption would be population growth at something closer to 1 million, half the projected amount. Assumptions about the economy to support even this growth are also dubious. The ABAG report, for example, fantasizes that by 2030 the Bay Area will increase its employment by 900,000 — a neat trick for an area that overall lost 300,000 positions over the past decade.

So, why wage war on the house? Some greens seem to regard the single-family house as an assault on eco-consciousness. Yet in many cases, these objections are overstated. Research supporting higher-density housing , for example, has routinely excluded the greater emissions from construction material extraction and production, building construction itself and& greenhouse gas emissions from common areas like parking levels, entrances and elevators.

Further, higher densities are associated with greater congestion, which retards fuel efficiency and increases greenhouse gas emissions, a factor not sufficiently considered. Given that less than 10% of Bay Area residents take transit — and barely 3% in its economic engine Silicon Valley — higher density likely would create greater, not fewer, emissions.

The ABAG report also studiously avoids mentioning the potential greenhouse gas reductions to be had by expanding telecommuting, which is growing six times faster than the fervently pushed transit commuting in the region. The Silicon Valley already has 25% more telecommuters than transit users. Clearly, by pushing telecommuting, you could get big reductions in GHG without a “cramming” agenda.

Ultimately the density agenda reflects less a credible strategy to reduce GHG than a push among planners to “force” Californians, as one explained to me, out of their homes and into apartments. In pursuit of their “cramming” agenda planners have also enlisted powerful allies – or perhaps better understood as ”useful idiots” — developers and speculators who see profit in the eradication of the single family by forcibly boosting the value of urban core properties.

In the end, however, substituting religion for markets and people’s preferences is counterproductive. For one thing, people “forced” to live densely will find other places to live the way they like — even if it means leaving California. This is already happening to middle class families in places like San Francisco and may soon be true of California’s traditionally middle-class-friendly interior as well.

In the end, two markets are likely to grow in the Bay Area. One is low-end rental housing for students and an expanding servant class — after all Google millionaires need people to walk their dogs and paint their toenails. The other is luxury retirement facilities for the region’s growing population of aging affluents. Once a self-consciously “cool” youth magnet, Marin County, for example, is now one of the country’s oldest urban counties, with a median age of 44.5; San Francisco is headed in the same direction.

Developers can drool over the prospects of building high-end assisted living joints for all those aging hippies who made their bundle during the state’s glory days and settled into places like Mill Valley. After all, unlike young families, these affluent oldsters will be able to afford indulging in the state’s mild climate, natural food restaurants and brilliant scenery. And with easily accessible medical marijuana and a good sound system for playing Grateful Dead recordings, the gray-ponytail set could be in for a hell of a good time, at least as long as it lasts.

This piece originally appeared at Forbes.com.

Joel Kotkin is executive editor of NewGeography.com and is a distinguished presidential fellow in urban futures at Chapman University, and an adjunct fellow of the Legatum Institute in London. He is author of The City: A Global History. His newest book is The Next Hundred Million: America in 2050

, released in February, 2010.

Photo by Mike Behnken