One of my girlfriends just invited me to attend her wedding ceremony next month. In our short conversation, I learned that she and her husband have already moved into their brand new, three-bedroom condo (we barely have any detached houses, called villas, in China), purchased a new car, and will have three separate wedding ceremonies: in the groom’s hometown, the bride’s hometown, and the city where they currently live. Based on this description, you are probably picturing a couple in their late 30s who must hold high-paying respectable jobs.

But that assumption would be wrong. They are an average young Chinese couple in their mid-20s who’ve only just graduated from university a couple of years ago. However, what they are planning for their wedding is typical in China today.

So how can they afford all this? Even in go-go China, many in reality can’t afford, and increasingly some are eschewing, the wedding-related expenses.

But how did we end up in the first place with a situation where pressures force some Chinese couples to disappoint their families, their friends and maybe themselves? Why have the wedding game become so patently insane even for the relatively affluent.

To answer this question, we must first become familiar with some Chinese wedding traditions. Primarily when it comes to the cost of a wedding, the groom’s family is expected to provide accommodations for the couple and pay for the wedding ceremony, while the bride’s family provides what could be loosely referred to as a dowry.

For my parents’ generation (those born between 1955 to 1965), the above mentioned wedding traditions translate into:

- The newlyweds live with the groom’s parents after getting married. Since housing was provided by the state owned companies in the 1980s, and younger generations were expected to show their filial obedience through living with their parents, no couple would even consider having a place of their own.

- In respect that China was still going through an extreme resource insufficiency phase in the early 1980s, my mother’s dowry only consisted of two brand new red quilts.

- Wedding ceremonies usually took place in the courtyard where people lived. Good friends would come to help cook a “feast” for a relative handful of guests.

Wedding ceremony in the 1980s

Now, after the massive economic changes that have happened over the past two decades, these three wedding traditions tend to follow a somewhat different pattern:

- The new couple absolutely must have their own home. In most cases the groom’s parents pay for this housing. It does not matter whether it is a three-story villa or a 40 square meter (425 square feet) bachelor apartment, whether it’s brand new or 20 years old. The key thing is that the property be ready for the new couple to move into. Depending on the family’s financial status, they either pay the full amount or at least the down payment on a mortgage, with the ownership under the new couple’s name. To pay for this, parents usually start saving as soon as their son is born.

- The dowry given by the bride’s family is either in the form of a brand new car, a hefty deposit into the newlywed’s bank account, or payment of the cost of interior decoration for their new home (new properties in China are usually delivered as little more than a concrete shell).

- Wedding ceremonies are commonly held at the best hotels in town, often with about 500 guests in attendance. The guests will be seated at tables of 10, while the new couple spends most of the time standing on a stage in front. Chinese wedding ceremonies have shifted from pure traditional Chinese style to a kind of bizarre formality. It is neither traditionally Chinese nor Western and typically includes: wedding rings, glamorous wedding pictures taken at a professional studio, multiple dresses worn by the bride, a lavishly decorated dining room and reception area in the hotel, fancy cars to transport the newlyweds and their entourage, hiring a famous host (MC), a huge feast, copious quantities of alcohol, firecrackers, and party favors that include chocolate and cigarettes.

Modern wedding ceremony

Don’t feel surprised if you are feeling dizzy just glancing at the list, you are not alone. Newlyweds often start preparing for their wedding ceremony several months in advance. Whether decorating their condo or taking wedding photos, or huddling with the wedding planner about the details of the ceremony, there’s pressure to get everything ready for the big day. By the time they can go on honeymoon, most couples would rather just stay home and rest.

The reality is, everybody knows and complains about how tiring it is to organize a wedding, yet most couples still repeat the same motions. Are they sacrificing their efforts for tradition? Not at all. They do it because weddings have become a way for people to show off their social status.

For the newlyweds it is like a competition with their peers. For the parents however, a fancy wedding ceremony seems to have more symbolic meaning. Due to the fact that they barely had anything when they got married, and most families only have one child, this seems a chance to realize their fantasies in ways virtually impossible for them to achieve 25 years ago. It is also a perfect occasion to show their old friends what a great life they have now.

Yet, no matter how exciting a Chinese wedding might sound, we all have to face a cold fact: there are many people in China – even among those ensconced in the middle class – who cannot afford these new wedding traditions.

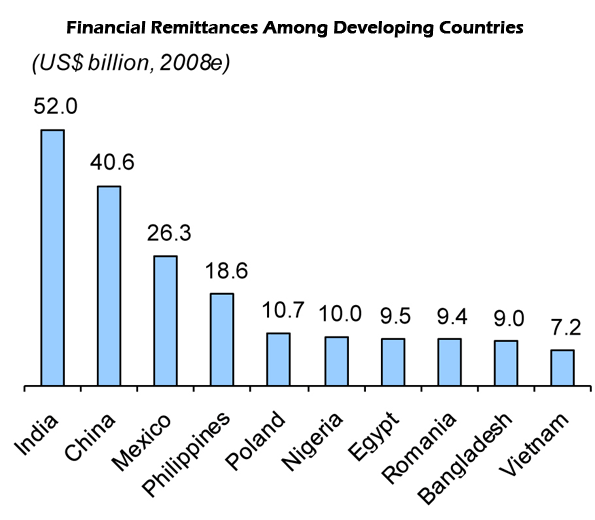

According to some unofficial calculations, in 2009 the total expenditure directly related to weddings was 600 billion CNY (92 billion USD). In 2010 the average wedding expenditure (excluding housing costs) for a Shanghai couple was 187,000 CNY (28,600 USD).

For people who do not have the luxury of being able to afford such tremendous costs, it is not uncommon for them to borrow from their friends and relatives in order to have an “unforgettable” ceremony.

Others see the problem from a different angle. If their daughter were to fall in love with a poor boy, some parents would not grant their permission for them to get married. At the same time, arranged marriages, blind dates and nationwide broadcast dating shows have started to pick up in popularity. The most frequently asked question for the involved parties is: do you have a house under your name?

Still others are attempting to break free from those so called social norms and traditions, by standing up and saying no to the modern social pressure.

A new word – “Luohun” (which directly translates as “getting married naked”) – emerged in 2008. It means that two people get married without buying a house, a car, wedding rings, having a fancy wedding ceremony or an exotic honeymoon. Instead, they spend only 9 CNY (1.4 USD) to get registered and obtain their marriage license from the state. Considering two people only get recognized in the community as a couple after their wedding ceremony in the old days, this represents a monumental shift in thinking.

Over the past 3 years, “Luohun” has won more favour, especially with those born after 1980. According to an online survey regarding marriage trends, 60% of those polled aged 20 to 35 indicated that they can accept this new concept. It’s a matter perhaps of re-adjusting to the realities of an economy that, while growing rapidly, has also become more expensive.

And there’s certainly some benefit in getting hitched without all the debts and encumbrances that are hard to bear for a young couple. After all, who wouldn’t want to get married naked?

Lisa Gu is a 26-year old Chinese national. She grew up in Yangzhou (Jiangsu) and lives and works in Nanjing (Jiangsu).

Photo by sheilaz413