Demography favors Democrats, as the influence of Latinos and millennials grows. Geography favors the GOP, as the fastest-growing states are solid red. A look at America’s political horizon.

In the crushing wave that flattened much of the Democratic Party last month, two left-leaning states survived not only intact but in some ways bluer than before. New York and California, long-time rivals for supremacy, may both have seen better days; but for Democrats, at least, the prospects there seem better than ever.

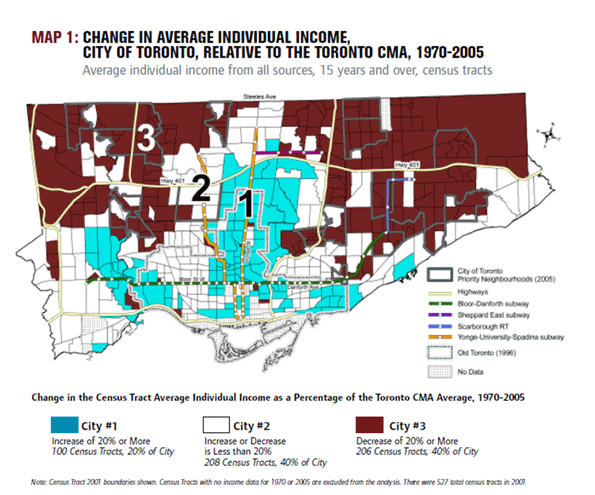

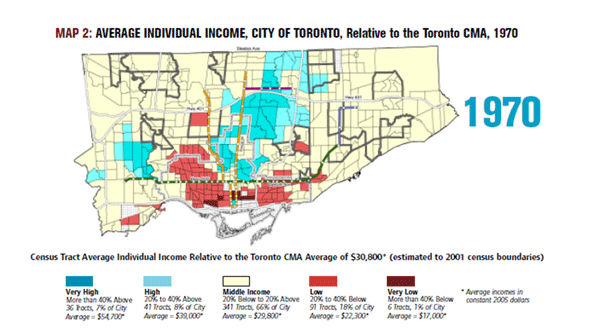

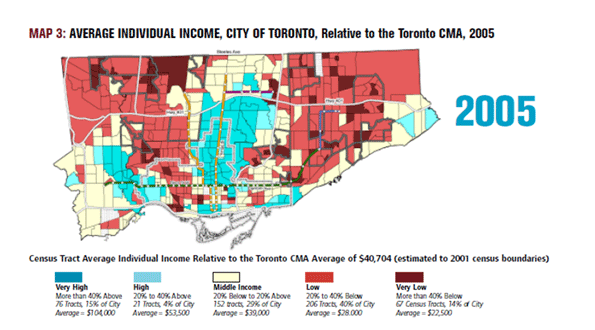

That these two states became such outliers from the rest of the United States reflects both changing economics and demographics. Over the past decade, New York and California underperformed in terms of job creation across a broad array of industries. Although still great repositories of wealth, their dominant metropolitan areas increasingly bifurcated between the affluent and poor. The middle class continues to ebb away for more opportune climes.

Each state has also developed a large and politically effective public sector. In both states, no candidate opposed to its demands won statewide office in 2010. At the same time, the traditional, broad-based business interest has become increasingly ineffective; instead, some powerful groups such as big developers, Wall Street, Silicon Valley, and Hollywood, became part of the “progressive” coalition, willing and able to cut their own deals with the ruling Democratic elite.

In New York, Republicans did capture a handful of seats in rural areas that have historically been friendly to the GOP, but in California the Republicans made no headway at all, even in rural areas. The difference here can be explained by demographics. In New York, the rural population is overwhelmingly Anglo; in California, much of it is Hispanic, a group that is both growing and, for the most part, tilting increasingly to the left.

Can the New York and California models be replicated in other states and yield political gold for Democrats? The answer depends on how these two economies perform over the coming decades.

Another state model competes for supremacy. It can be found in Texas, the Southeast, and parts of the intermountain West. The hallmarks are fiscal restraint and an emphasis on private-sector growth. If these free market-oriented states can produce better results than the coastal megastates, with their emphasis on government they could own the political future.

Demographics: The Democrats’ Best Hope

Right now, demography is the best friend Democrats have. Over the next four decades, the two groups that will increasingly dominate the political landscape are Hispanics and millennials (the generation born between 1983 and the millennium). Both groups tilted leftwards in recent elections. This trend should concern even the most jaded conservatives.

The Latinization of America, even if immigration slows, is now inevitable. Only 12 percent of the U.S. population in 2000, Hispanics will become almost 25 percent by 2050. As more Latinos integrate into society and become citizens, they are gradually forming a political force. Since 1990, the number of registered Latino voters swelled from 4.4 million to nearly 10 million today.

Anglos—60 percent of whom supported Republican congressional candidates in 2010—are beginning to experience an inexorable decline. In 1960, whites accounted for more than 90 percent of the electorate; today, that number is down to 75 percent. It will drop even more rapidly in the coming decades, with white non-Hispanics expected to account for barely half the nation’s population by 2050.

California and New York are laboratories of the new ethnic politics. In New York, Latinos represent roughly 12 percent of the voters, while the overall “minority” vote has risen to well over 30 percent. California has, by far, the nation’s largest Hispanic population and Latinos are now roughly 24 percent of eligible voters. Overall, non-whites constitute well over a third of the electorate.

The growth of the Latino vote works to Democrats’ advantage. Until the GOP-sponsored passage in 1994 of the anti-illegal alien Proposition 187, Latinos in California routinely voted upwards of 40 percent Republican (and even did so for Governor Arnold Schwarzenegger in 2006). This year, barely one-third of California Latinos supported Republican candidates Meg Whitman and Carly Fiorina.

The Republican embrace of what is perceived by Hispanics as nativism has clearly alienated Latinos. This applies not only to California but also in Arizona, where Latino voters are now 18 percent of the total; in Nevada, they represent 14 percent and played a critical role in re-electing Majority Leader Harry Reid.

This shift is all the more remarkable given the fact that many Democratic policies, on both social issues and regulations squashing economic opportunity, are at odds with Latino social conservatism and aspirational instincts.

Of course, Latino voters are not the same in every corner of the country, and Republicans can do well with Hispanic voters if conditions are right. For example, Latinos in Florida and New Mexico support Republican candidates far more than in California or New York. Texas Republicans picked up two predominately Latino house districts along the Mexican border this year. And several recently elected high-profile Latinos—Florida Senator Marco Rubio and Governors Brian Sandoval in Nevada and Susan Martinez in New Mexico—earned strong Hispanic support (Rubio won more than 45 percent of Latino voters in a three-way race). Latino Republican candidates also won in Washington State and, of all places, Wyoming.

The elevation of such emerging leaders could eventually turn the Latinos into a successfully contested group. But there is also a distinct possibility that emboldened nativist-oriented Republicans (backed largely by their older, Anglo base) could embrace policies, such as abolishing birthright citizenship, that seem almost calculated to alienate Latino and other immigrant voters.

Millennials: Growing Up, Staying Left?

Latinos and minorities are not even the GOP’s biggest demographic challenge. Millennials, the so called “echo boomers,” constitute a growing percentage of the electorate. They also tilted heavily Democrat. In 2008, millennials accounted for 17 percent of the nation’s voting-age population; by 2012, that share will grow to 24 percent. By 2020, they will account for more than one-third of the total population eligible to vote. Their power will wax while the seniors’, who broke decisively for the GOP this year, will inevitably fade.

Millennials and generation X, their older brothers and sisters, constitute the majority of self-professed Democrats, note Mike Hais and Morley Winograd, authors of the forthcoming Millennial Momentum: America in the 21st Century. Last November, they supported Democratic candidates 55 percent to 42 percent, although their turnout flagged compared to what it was in 2008. They can be expected to turn out in bigger numbers in the 2012 presidential election.

A connection exists between the Latinization trend and millennial voters. Boomers were 80 percent white; among millennials, at least the younger cohorts, the majority are from minority households.

More critically, on a host of issues—from the environment to gay rights and economic re-distribution—this generation appears well to the left of older ones. One hopeful note for libertarian-minded Republicans: almost half believe that government is too involved in Americans’ lives (in this sense, their views are similar to those of older generations).

Can millennials and generation X-ers be turned toward the center? History suggests this is at least possible. Boomers started off relatively left of the mainstream, notes political scientist Larry Sabato (although as Hais and Winograd suggest, Boomers were never as “left” as their louder, and often better-educated, generation “spokespeople”). In 1972, their first appearance at the ballot box, they split between Richard Nixon and George McGovern while older voters went overwhelmingly with President Nixon. In 1976, they helped put Jimmy Carter in office.

But, over time, Boomers clearly shifted to the center-right, and eventually tracked close to the national averages. They supported Ronald Reagan in 1984, Democratic Leadership Council standard-bearer Bill Clinton, and George W. Bush. Politically, Sabato notes, “the boomers have become their parents.”

Will today’s younger voters follow a similar arc? The key lies with how Republicans deal with critical issues, such as gay rights and the environment. It should be sobering for Republicans that a popular conservative like Senator Jim DeMint—the putative godfather of the Tea Party—lost overwhelmingly among South Carolina millennials by 54 to 46 percent against a marginal Democratic candidate.

“This doesn’t say that the millennials will necessarily be Democrats forever and could never vote for Republicans,” notes Hais, who surveyed generational dynamics for Frank N. Magid Associates, an Iowa- and Los Angeles-based market research firm. “Obviously, the Democrats will have to produce, especially in the economy. But, I think that for millennials to begin to vote for Republicans, it is the Republicans and not millennials who will have to do most of the changing. The Republicans will have to come up with a way to appeal to an ethnically diverse, tolerant, civic generation—something they haven’t done very well to date.”

Geography: The Great Republican Advantage

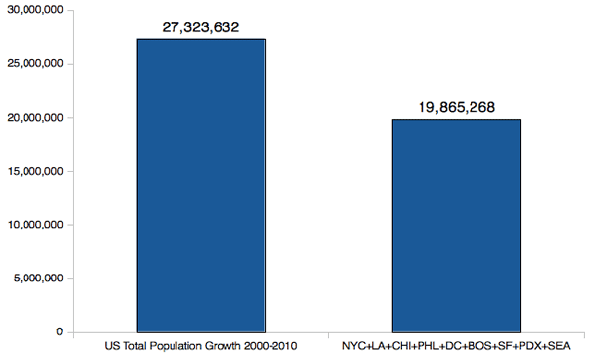

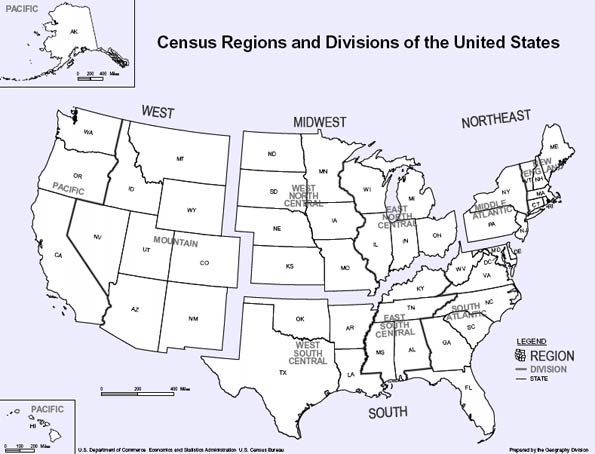

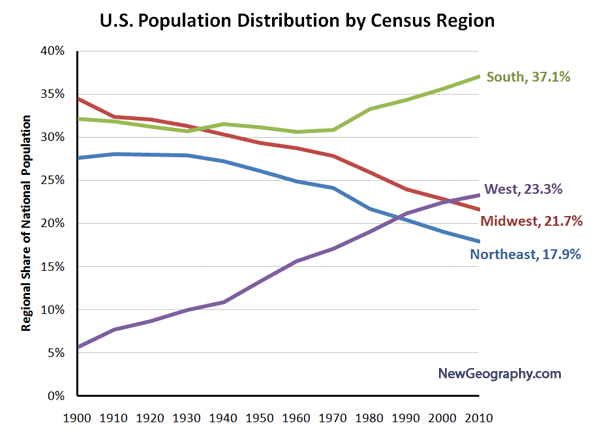

Demographics may seem a long-term boon for Democrats, but geographic trends tilt in the opposite direction. Actually, Republicans did exceptionally well in the country’s fastest-growing places, both within metropolitan areas and by state. Democrats won the urban core, winning it by almost two-to-one in an otherwise disastrous year for them. But this is not where population growth is concentrated. Out of the 48 metropolitan areas, notes demographer Wendell Cox, suburban counties gained more migrants than core counties in 42 cases over the past decade. Overall suburbs and exurbs accounted for roughly 80 percent or more of all metropolitan growth.

Suburbs and exurbs, where a clear majority of the country lives, are where American elections are determined. Dominated by the automobile single family houses, these areas shifted heavily to the Republicans this year, voting 54 to 43 percent for the GOP. Unless there is a startling economic development or the unlikely imposition of density-promoting national planning policy, the periphery is likely to remain the ultimate “decider” in American politics for the foreseeable future. The next generation of homebuyers, the millennials, note Hais and Winograd, also identify suburbs as their “ideal” place to live—even more than their boomer parents.

Immigrants also are demonstrating a strong preference for the suburbs. Since 1980, the percentage of immigrants who live in the suburbs has grown from roughly 40 percent to above 52 percent. They also remained the preferred home for most boomers as they age.

Republicans also dominate the fastest-growing states: Virginia, Utah, Florida, North Carolina, and, most importantly, Texas. Over the past decade, more than 800,000 more people moved to Texas than left the Lone Star State. In contrast, New York suffered a net migration loss of over 1.6 million, while California, once the nation’s leading destination, lost almost as many. Texas, Florida, and Virginia will gain congressional seats while New York will lose seats and California, for the first time in its history, will add none.

More important still are the reasons driving this migration: job growth, cost structure, taxes, and regulation. While the highest earners in Hollywood, Silicon Valley, or Wall Street may still flourish in the two big blue states, jobs are evaporating for many middle- and working-class residents.

For the vast majority of middle- and working-class people, the growth states are increasingly attractive places for relocation. Over the past decade, states like Texas, Virginia, North Carolina, and Utah, according to a Praxis Strategy Group analysis, enjoyed faster growth in middle-income jobs than in the deep blue strongholds. Texas, for instance, has increased middle-income jobs at seven times the rate of California over the past decade.

This job growth extends beyond low-wage jobs at places like Walmart. Over the past decade, Texas has increased its number of so-called STEM jobs (science, technology, engineering, and mathematics related jobs) by 14 percent, well over twice the national average. Virginia and Utah performed even better. In contrast, New York and Massachusetts grew high-tech jobs by a paltry 2.4 percent, while California lagged with a tiny 1.7 percent increase.

Jockeying for the Future

In its first two years, the Obama administration tried to reverse these geographic trends by steering funds into universities, mainly those located in big cities and along the Northeast and California coasts. This tilt was natural for an administration which one Democratic mayor from central California described as “Moveon.org run by the Chicago machine.”

The Obama administration’s “green” policies are also designed to favor major dense urban areas, with large increases in transit funding, high-speed rail projects, and grants for pro-density “smart growth” policies. But with the resounding defeat in November, the drive to force the population into dense and normally democratically inclined cities seems certain to ebb. The demise of the fiscal stimulus will put increased pressure on states like New York and California to cut down their public-sector growth, further threatening their weak recoveries.

In the coming years, budget-constrained states will have to focus on private-sector jobs and growth. Given the likely tight job market over the next decade, particularly for minorities and millennials, Republicans could do well to demonstrate the superiority of their pro-enterprise model.

Currently, red-leaning states top the list of states with the “best” business climates. Texas, North Carolina, Tennessee, and Virginia topped a recent survey by Chief Executive Officer magazine. In contrast, the bottom rungs are dominated by New York and California, as well as by longstanding Democratic bastions Michigan, New Jersey, and Massachusetts.

To succeed, Democrats will need to prove capable of something other than a reverse Midas touch. They will need to develop a pro-growth, job-oriented program, something that they have not done well since the Clinton era. The decline in the numbers of pragmatic, business-oriented Democrats at the state and federal levels could make that job tougher than ever.

It is still possible that, as millennials and Latinos flock to the suburbs, blue state demographics could overwhelm red state geography. In a decade, for example, Texas will likely be more far Latino than Asian; by 2040, according to demographer Steven Murdoch, the overall minority population, could be three times that of Anglos. At the same time, surging high-end employment will bring more educated, socially liberal people to the state. If these groups continue to favor the Democrats, Texas and other deeply red states could turn purple if not blue.

In the long run, each party has strong cards to play. Demographic shifts favor Democrats, while geography tilts to the Republicans. Ultimately, the winner will be the party that offers a successful strategy for economic growth—but without culturally alienating the demographic groups destined to hold the balance in the political future.

This article originally appeared at The American.

Joel Kotkin is executive editor of NewGeography.com and is a distinguished presidential fellow in urban futures at Chapman University. He is author of The City: A Global History . His newest book is The Next Hundred Million: America in 2050

. His newest book is The Next Hundred Million: America in 2050 , released in February, 2010.

, released in February, 2010.

Photo by Eric Langhorst

. His newest book is The Next Hundred Million: America in 2050

, released in February, 2010.