What comes to mind when you think about Orange County? Probably, images of lascivious housewives and blonde surfers. And certainly, at least if you know your political history, crazed right-wing activists, riding around with anti-UN slogans on their bumpers in this county that served as a crucial birthplace of modern movement conservatism in the 1950s.

Yet today, Orange County—or the OC, as locals call it—is becoming a very different place. Today close to half the population of this 3-million person region south of Los Angeles are minorities, primarily Latino and Asian, and the county’s future belongs largely to them.

These days you color the OC both ethnically diverse and politically purplish. The Republican share of the electorate has dropped from 55 percent in 1990 to under 40 percent today. Two of the seven people who represent the area in Congress are Latino, and a third is of Middle Eastern descent. Four of the 10 people the county sends to Sacramento are minorities, three Asians and one Hispanic. Asians, now 20 percent of the local population, represent the majority on the county Board of Supervisors. In 2012 Mitt Romney took the county with 53 percent of the vote; this year it may be far closer than that.

The cultural landscape is also changing. What was historically a land of hamburger dives (we still have some) and little Mexican restaurants (we have many) is now home to some of Southern California’s best restaurants—including two on the top 30 list ofLos Angeles Times food critic Jonathan Gold. The OC is also home to one of the country’s leading venues for new plays, South Coast Repertory. Alongside the ubiquitous malls have arisen some of the nation’s most innovative urban environments, some of them revived small town main streets, from Santa Ana’s 4th Street Market to Orange to Laguna Beach and Fullerton.

When urbanists talk about the future, they usually imagine an environment of dense buildings, connected by train transit and highly centralized workplaces. Yet the bulk of all the nation’s economic and population growth takes place in “post-suburbia,” a term first applied to the OC. Post-suburbia, noted two urban scholars in 1991, reflects a “decentralized, multi-centered area” that puts “into question the mainstream urbanist’s concept of central-city dominance.”

This new geography of urbanity—far more than the much-discussed recovery of the urban core—dominates our metropolitan life; since 2000 over 80 percent of all metropolitan area jobs and population have remained outside the urban core. Post-suburbia predominates among our most demographically and economically vital regions, including STEM-intensive regions such as Silicon Valley, the northern reaches of Dallas, the western suburbs of Houston, Johnson County west of Kansas City or virtually anything around Raleigh or Austin. Orange County’s STEM sector (PDF) has expanded at twice the rate of L.A. County, despite all the considerable hype about the emergence of “Silicon Beach.”

Post-suburbia was not designed to be a traditional commuter suburb, where people pile onto trains or the highways to get “downtown.” The vast majority of OC people work in the plethora of county worksites, and many others, particularly from the Inland Empire to the east, drive into the area for work.

What places like the OC sell is both work and quality of life. The area ranks 10th out of 3,111 counties in the U.S. for natural amenities, and even outpaces Los Angeles among cities for best recreation. The roads are less congested, and there’s more open space. Urban Los Angeles has 9.4 acres of parks and recreation areas per 1,000 residents; Irvine has 37 acres per 1,000 residents, meaning that over 20 percent of the city’s land is dedicated to parks, five times the national average. No wonder the Irvine city motto is “Another Day in Paradise.”

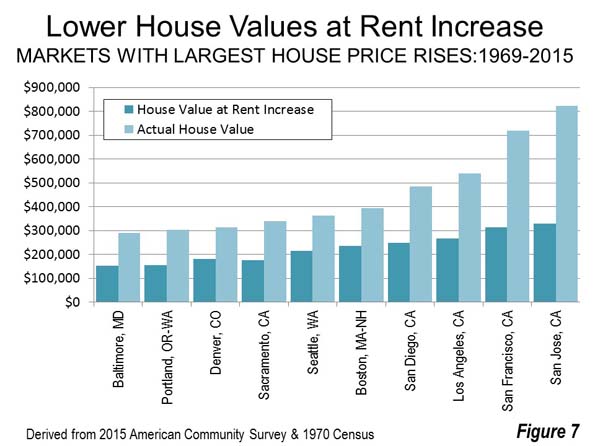

All changes are not for the better, of course, and one of the chief problems in today’s OC is the cost of housing. Irvine is a city of 236,000 people that was once a classic Anglo suburb and is now 40 percent Asian and less than half white. Housing, once distinctly middle class, now averages near $800,000, in large part due to purchases by Chinese investors. According to the real-estate information firm DataQuick, the 25 most common last names of homebuyers last year were Chen, Lee, and Wang.

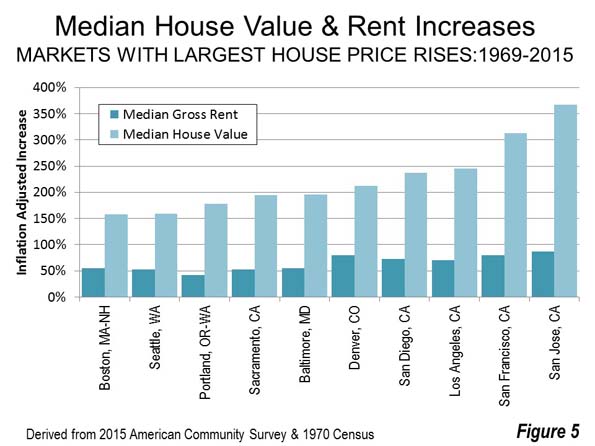

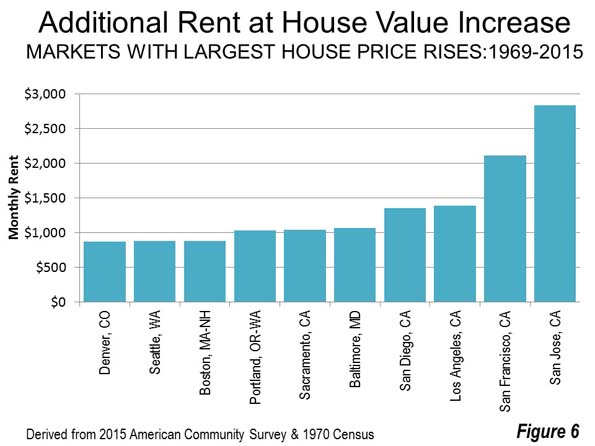

The landscape has also changed, with massive rows of multi-family houses crowding the wide boulevards of the city, clogging traffic and making “paradise” a little less bucolic. Since 2000, Orange County’s prices have increased 3.5 times that of incomes, one of the highest rates of increase in the country. The middle class who came to experience a Disneyland urban existence now finds the county largely beyond their means.

These price increases have benefited many older property owners, particularly along the strip near the Pacific Ocean—now among the most expensive places to live in the country—but have sent rents soaring as well. Santa Ana, right next door to Irvine, is home now to much of the county’sgrowing homeless population, now estimated at 15,000, in large part reflecting rents increasingly out of reach to the working poor. If one full-time worker rents a two-bedroom apartment in Orange County they can expect to spend over 40 percent of their income (PDF) on rent.

High prices are making the OC increasingly unaffordable for young families. Despite the assertions by density advocates, most millennials remain deeply interested in home ownership and generally move to places they can afford a house, which is usually somewhere else. This is one reason why Orange County, once an epicenter of youth culture, is going grey—and quickly.

Orange County’s old folks feel little reason to move, short of being carried out feet first. The OC’s perfect weather, coupled with Proposition 13 protections, keeps seniors in their homes long after their offspring have left. With grey ponytails common even among surfers, the OC by 2040 is on track to be the oldest major county in California.

The big hope may be the aging of millennials who by 2018 will on average be over 30. With safe cities and exceptional schools, the OC is a great place for “grownup millennials” looking to raise a family. Kina De Santis, CMO of the Orange County-based tech startup Motormood, calls it “very family oriented,” and Lee Decker, CMO at IGNITE Agency praises it for having the right environment for those with families who still want to focus on their startups, explaining, “As I prepare to get married to my kick ass and ridiculously supportive fiancé, I’m deciding to firmly root myself here in OC.”

In a famous scene from the play Hamilton, the future treasury secretary and his friend, Marquis de Lafayette, celebrate America’s revolutionary victory with the words—“immigrants, we get the job done.” As the OC evolves in the coming decades, the fast-growing foreign born population, and their offspring, will play the leading roles.

In 1970, 80 percent of OC residents were non-Hispanic white. Many feared new immigrants, with the OC Grand Jury—a body of 19 to 23 members impaneled for one year to investigate and report on both criminal and civil matters within the county—in 1993 calling for a three-year ban on all immigration. Since 2000, the area’s Latino growth rate has been roughly 50 percent greater than Los Angeles’s. By 2014, the non-Hispanic white population dropped to 43 percent of the population, while the Hispanic share rose to 35.3 percent.

The growth of the Asian population has been, if anything, more dramatic. One critical turning point was the arrival of the Vietnamese after the 1975 fall of Saigon, which turned Westminster from a sleepy town to one of the largest settlements of Vietnamese outside the mother country. More recently, Koreans and ethnic Chinese have arrived in significant numbers.

Since 2000, Orange County’s Asian population has been growing at roughly 3 percent annually, roughly 50 percent faster than Los Angeles County. The OC’s rate is roughly equal to that of such Asian migration centers as Santa Clara, San Francisco, and New York. Overall, Orange County is the nation’s fourth most heavily Asian county over 1 million, at roughly 20 percent.

Although they differ in appearance from the old OC denizens, these new OC residents are attracted by many of the same things that brought earlier immigrants to the area—single family homes, parks, and good public schools. They have created a dazzling series of ethnic “villages” from the heavilyVietnamese band from Westminster to Garden Grove, to the expanding “Little Korea” in the same area, the “Little Arabia” in Anaheim and the El Centro Cultural de Mexico, located in Santa Ana.

These newcomers and their kids are reshaping the OC’s culture, which plays a huge part in the area’s economy, employing well over 50,000 people; overall, the county lags only New York and Los Angeles in terms of the role of creative industries. In the past much of this was tied to the surfer culture, most notably serving as the fashion capital of the surf wear world—known to some Boomer adepts as “Velcro valley,” built around surf wear icons Hurley, Quicksilver, and O’Neill. The creative sector is adding jobs across a range of other industries such as architecture and interior design. Orange County is increasingly proving itself capable to draw the talent and support the lifestyle to compete with other creative powerhouses such as Los Angeles and New York.

Immigrants provide much of the impetus. Much of the best food in Orange County is produced by newcomers and their children. The immigrant reshaping of the OC also is reflected in the bustling ethnic shopping malls that dot the county, packed with shops selling groceries, clothing, travel packages, and videos to the increasingly diverse population. Even more important is the growing cross-fertilization of ethnic styles and tastes. Urban amenities such as locally owned restaurants, bars, and retail shops at Huntington Beach’s Pacific City, keep things interesting as people are increasingly looking to spend their money on regionally tuned experiences (PDF), rather than typical suburban chains.

Perhaps the most influential figure here is Shaheen Sadeghi, a Persian-American and former CEO of the surf wear line Quicksilver. Sadeghi’s company has taken a dozen sites, many of them deserted industrial and warehouse spaces, and converted them into exciting urban spaces. Perhaps his most impressive is the Packing House in Anaheim, a gigantic food court located in a former fruit-packing facility, which teems with ethnic food vendors.

Critically, Sadeghi’s vision goes well beyond the usual urbanist dreamscape of a culture dominated by hip singles and childless couples. He wants to appeal to families, just in an updated way. “The international community tends to be more family oriented,” he notes, “on the weekend at the Packing House you’ll see a family from Asia putting all the tables and chairs together.”

Building this new vision for OC will not be easy, he realizes, given the regulatory vise exercised by California regulators on small business. Yet he sees the area’s decentralization—epitomized by the county’s 34 separate cities—as providing consumers with greater diversity and choice. “Each city has its own identity, brand, and culture,” he suggests. “It’s like there’s more cookies in the cookie jar.”

Sadeghi is bringing the old OC model to the future, proving that post-suburban “sprawl” can coexist with diversity and culture. Like the visionaries who created Disneyland, Irvine and other earlier iconic expressions of the county’s past, innovators like Sadeghi are willing to buck models, urban or otherwise, in pursuit of a unique sensibility. The OC should not aspire to become another Brooklyn, he suggests, but exploit all its natural advantages, as well as its efflorescent diversity to reinvent itself. “After all,” he says with an inner reassurance those of us who live here tend to have, “we still have a couple of things no one else has—ocean and good weather. And they aren’t going away.”

Joel Kotkin is executive editor of NewGeography.com. He is the Roger Hobbs Distinguished Fellow in Urban Studies at Chapman University and executive director of the Houston-based Center for Opportunity Urbanism. His newest book, The Human City: Urbanism for the rest of us, will be published in April by Agate. He is also author of The New Class Conflict, The City: A Global History, and The Next Hundred Million: America in 2050. He lives in Orange County, CA.