Is New York City helping or holding back Upstate New York?

Towards the end of times, when all of mankind congregates in a final purgatory to draw the main lessons of this grand adventure called Life, there will be special attention paid to the centuries’ long efforts at harmonizing individual happiness with the needs of the collective. There will be seminars on leadership and war. There will be a thick chapter on the blessings and dangers of science. There will be a long section, co-written by poets and undertakers, on the success of freedom and the failure of tyranny. There will be wonder and consternation about religion and the nature of the universe. And there will be, inevitably, extensive reporting on economic ideology.

Here, a slim primer on laissez-faire will easily outshine ponderous encyclopedic tomes on communism, socialism and other failed -isms. Capitalism, the word and the theory, will be presented as a zealous and perhaps unnecessary attempt at creating a code for laissez-faire, something that occurs naturally. Cronyism will be understood as the corruption and distortion of laissez-faire and the phrase crony capitalism will be dismissed as an oxymoron and an unwarranted amalgamation.

Finally, there will be a footnote on dirigisme, or the state’s effort at orchestrating and controlling economic growth by directing public and private funds towards its own selection of industries and businesses. Some will call it national industrial policy, or picking winners and losers. Others will deride it as a pretext for cronyism to assert itself under the guise of policy. There will be references to its various forms and intensities in France under De Gaulle, in Japan with MITI and in many other places.

It will be mentioned in passing by bemused Americans that it was also tried once upon a time in New York State and that it led to the same dead end of wasted resources and corruption. Among the evidence presented will be reports of public/private investments organized by the state’s government in the early 2000s and the uncovering of a scandal in 2016.

New York, Two States of Mind

Meanwhile, if we rewind and zoom in on present day New York, it is clear that there is no other state in the nation like the Empire State. It has New York City, a dynamic universal metropolis, and it has a huge land area Upstate that is demographically and economically stagnant. No other state is so economically polarized. In California, Texas and Florida, the population and wealth are less geographically concentrated.

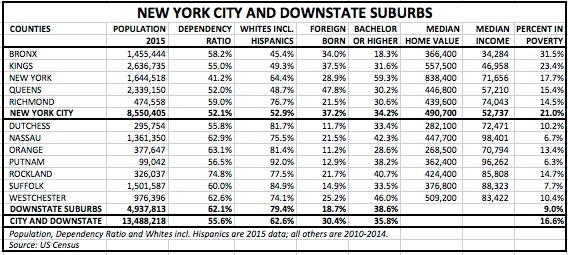

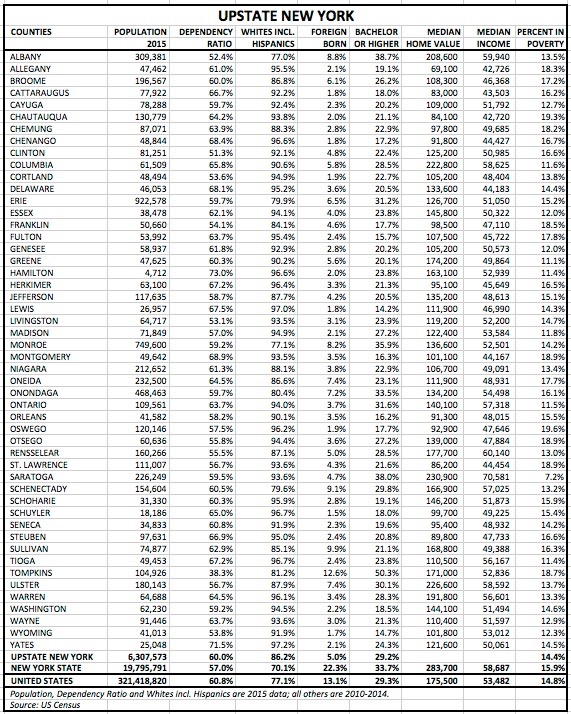

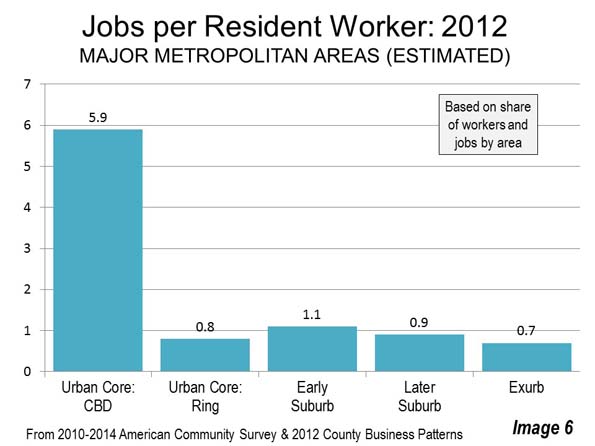

On many measures, New York City and State have little in common. Consider the following:

New York City covers less than 1% of New York State’s land area and is home to 43% of the State’s population. Including downstate suburbs, the New York City metro area adds up to 65% of the state’s population.

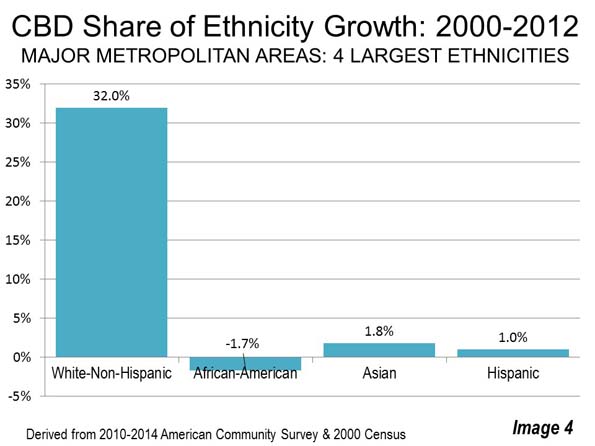

In the City, 53% of people are white (including hispanics) and 37% are foreign-born. Outside the City, 83% are white and 11% foreign-born. If you exclude seven downstate counties that are near the City (see tables), the percentage of the Upstate population who are foreign-born drops to 5%. By way of comparison, the entire US population is 77% white and 13% foreign-born. So New York City is less white and much more foreign-born than the United States. And New York State is more white and much less foreign-born.

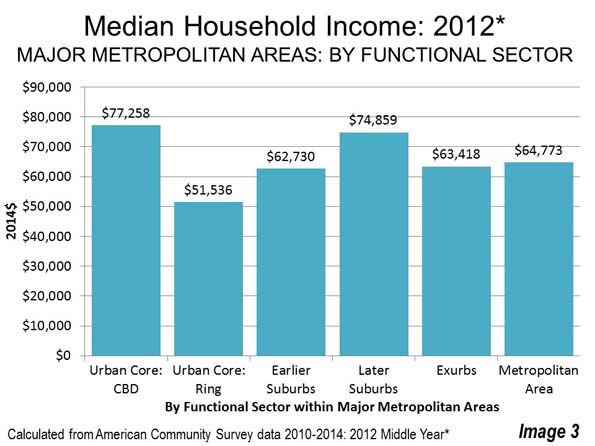

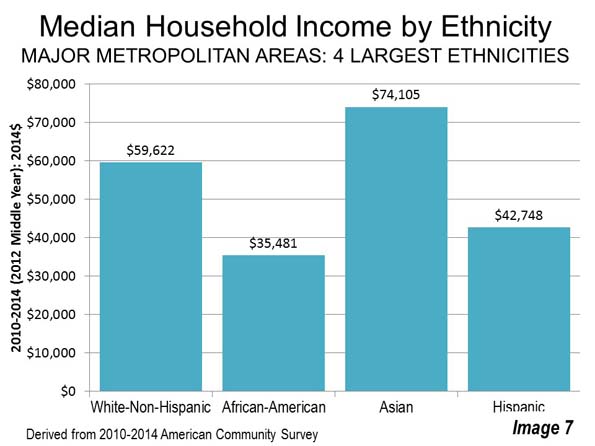

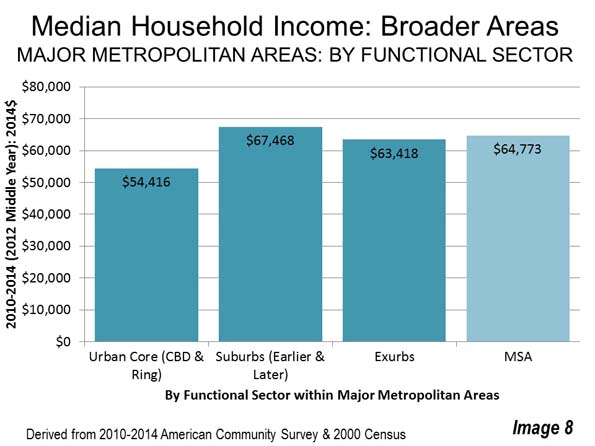

Because there is a higher percentage of poor people in the City, notably in the Bronx, the median household income at $52,737 is lower than the $58,687 for the state overall. However the average income is much higher in the City due to its high-paying jobs in law, media, finance and health care. The weight of the 1% or 5% highest earners would be more visible in the average than in the median. As shown in the table, the median income in the downstate suburbs is significantly higher than in the City or Upstate. The median household income in the United States is $53,482.

Home values are much higher in the City and surrounding counties than in the rest of the state. In the City, the median home value is $491,000 whereas a median home can be obtained in most counties Upstate for less than $200,000. The higher ratio of median home value to median income underlines the greater income disparity in the City.

In New York county (Manhattan), the median home value is $838,000 or 12 times the median household income of $72,000. This would be unsustainable if the average income did not deviate significantly from the median, or in other words, if there was not a small percentage of people earning large and very large incomes every year. In Manhattan, the average income of the top 1% is $8.1 million. And the average income of the bottom 99% is $70,468. The ratio of the first to the second is 116. (sources: Economic Policy Institute, howmuch.net).

By contrast, in Allegany county for example, the median home value is only 1.6 times the median income. The average income of the top 1% is $358,554 million and that of the bottom 99% is $25,595. The ratio of the first to the second is 14.

In the United States overall, the median home value is $175,500, or 3.3 times the median income. In 2013, the average income of the top 1% was $1.1 million and that of the bottom 99% was $45,567, resulting in a ratio of 25.

It is tempting to conclude from these figures that New York City is doing very well and that New York State is doing, depending on one’s perspective, as well or as poorly as the rest of the country. But on closer scrutiny, both the City and the state face some challenges that are unique to New York.

Stagnant Demographics

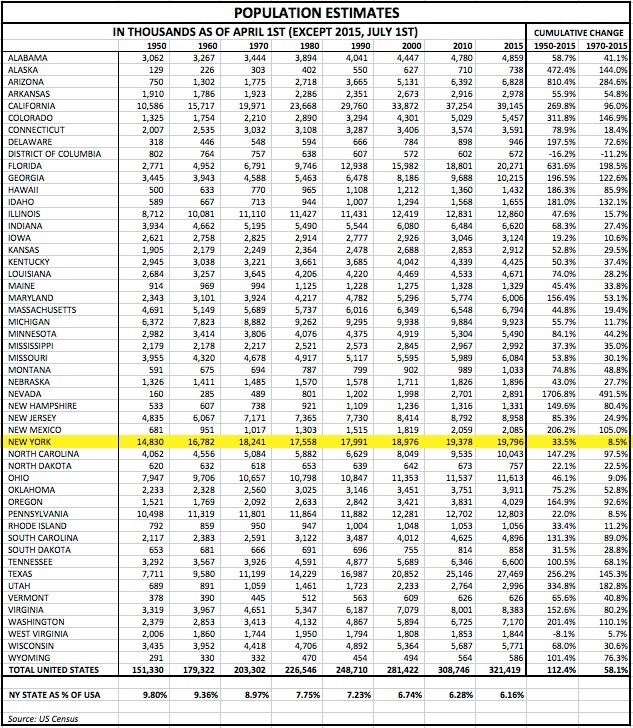

The most obvious is the fact that the size of New York’s population has barely budged in the past forty-five years except for getting older. In 1970, there were 18.2 million people in New York State and in 2015 only 19.8 million. This change amounts to an 8% cumulative increase over 45 years, a very low figure compared to the 58% growth in the US population over the same period.

If there had been instead a modest annual population growth rate of 0.5% due to new births, the cumulative growth over 45 years would have come to 25%. Further, because New York City is a magnet for new immigrant arrivals, one would expect that cumulative growth to have exceeded 25%. Instead, the 8% figure over 45 years means that there has been a steady large migration of New Yorkers towards other states.

New York State had 9% of the country’s population in 1970 and 6.2% in 2015. The state and City have not been choice destinations except for people seeking employment in specific industries or for recent immigrants looking for a social gateway into the United States via their own national communities.

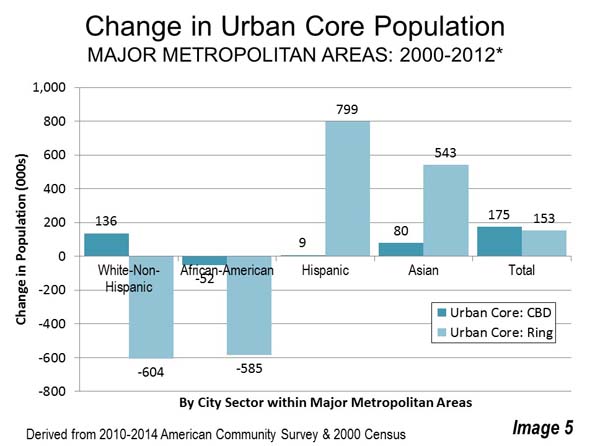

Also worth noting is the fact that the state’s entire population growth (800,000 people) since 2000 has been concentrated in the City and downstate suburbs. The size of the population Upstate has flatlined for years while getting older.

Of course, this stagnation is partly explained by the large migration over several decades of Americans heading to sun belt and mountain states in the West, South and Southwest. No doubt the invention of affordable air conditioning and the expansion of the interstate highway network facilitated this exodus from North to South.

Other legacy large industrial states like Pennsylvania and Ohio also show weak single digit growth in the period 1970 to 2015. But neither has a large universal metropolis like New York City and neither shows as great a divide between its largest city and Upstate region. Meanwhile the populations of California, Colorado, Texas and Utah have doubled or more than doubled in 1970-2015, as have those of Southeastern states like Florida, Georgia and the Carolinas. Arizona has quadrupled and Nevada grown six fold, albeit from a low base in both cases.

A closer to home comparison is only marginally more comforting. If New York State was a state on its own today, its demographics would compare poorly to those of its neighbors. Next door Vermont and New Hampshire have both grown smartly despite lacking a significant industrial base and large metro areas. The largest employers in both states are IBM and a collection of ski resorts, hospitals, colleges, retail stores and insurers/banks/asset managers. New Hampshire has also benefited from its proximity to Boston, with some tax-minded commuters choosing to declare residence in the southeastern corner.

Part of this may be a public relations issue. Both New England states have done a better job than New York in associating their names with autumn foliage, winter sports and summer boating even though New York has similar colors, ski areas and lakes.

Vermont or Upstate New York?

And compared to New England, Upstate is rarely showcased in movies. Wikipedia has long lists of movies set in New England and in New York City but no such list for New York State. In the 1987 movie Baby Boom, management consultant J. C. Wiatt (Diane Keaton) escapes New York City’s chaos and complexity, and dumps New York State without a thought on her way to a simpler life in Vermont that ends up delivering not only space, beauty and peace but also greater wealth and even romance.

Weather can also be an important factor. Some parts of New York State get much more snow and have many more overcast days every year than do Vermont, New Hampshire, Pennsylvania and Ohio.

Policies for Upstate

Nonetheless, if weather is the work of Providence, government policy is very much man-made and should be designed to capitalize on the state’s assets and to mitigate its handicaps. The empirical evidence so far is that policy has not done enough to improve conditions Upstate.

To the South and West, both Pennsylvania and Ohio have enjoyed a better economy than Upstate thanks in part to the shale energy boom while New York maintains a ban on fracking. It can afford to do so thanks to its large tax revenues coming from the City. According to a 2011 Rockefeller Institute study, in 2010 New York City contributed 48.7% of the state’s tax revenues. The downstate suburbs contributed an additional 23.6%, leaving a modest 27.7% coming from the rest of Upstate.

These revenue percentages don’t deviate significantly from the weight of the population in the various regions. But the same Rockefeller Institute study showed that expenditures are more favorably weighted towards Upstate which received 42.2% of the state’s spending while the City and downstate suburbs received 40% and 17.7% respectively. In other words, Upstate has not been self-sufficient in terms of tax expenditures vs. tax receipts and has been receiving funds from the metro area.

Some will allege that this is how a state should operate. Less productive areas receive assistance from more productive ones. But New York State could do better by making itself more tax-friendly to businesses and households. Our populyst state-by-state analysis shows that a median household in New York keeps 82.5% of its income after taxes, a percentage that places the state in the lowest quintile of all states on this measure. By contrast, a median household in Florida, Tennessee, Nevada, Texas or Washington State keeps over 88% of its income. The difference in after-tax take-home incomes would be even greater for higher earning households.

The table below shows total and per capita state government tax collections for fiscal year 2013. On a per capita basis, New York State is in the first highest quintile for all state taxes, and second only to Connecticut for individual and corporate income state taxes. Among states with large populations, it is comfortably first in both categories, higher than California, Illinois, Pennsylvania and Ohio, and much higher than low-tax Texas and Florida.

None of this may be a surprise, given that New York routinely ranks among the highest-tax states in the country. But instead of cutting taxes across the board and letting the market work its magic, the state has opted to launch a number of targeted public and public/private initiatives to reenergize the economy Upstate.

Start-Up NY offers tax free zones to research-oriented businesses. In order to qualify, a business must partner with a university and must operate in one of the sectors targeted by the program.

Judging by this recent announcement, the impact so far has been helpful on a local level but negligible in improving the state’s overall condition:

Governor Andrew M. Cuomo today announced that 18 new businesses will join START-UP NY, relocating or expanding their operations across the state through innovative tax-free zones associated with public colleges and universities. These 18 businesses have committed to create at least 135 new jobs and invest nearly $10 million over the next five years in Western New York, the Southern Tier, Central New York, the Capital District, New York City and Long Island.

and further:

START-UP NY now has commitments from 172 companies to create at least 4,175 new jobs and invest more than $229.2 million over the next five years in New York State.

That comes to an average of 24 jobs and an investment of $1.33 million per company, small figures in a state of 19 million people and a GDP of $1.4 trillion. Perhaps the choice of a few sectors and the required linkage to a college should be removed and a tax abatement should be offered to all startups.

Though its impact is small, Start-Up NY at least has the distinction of a hip dynamic name. By contrast, other initiatives that have a greater immediate dollar impact are encumbered by vaguely Soviet-sounding names such as the Regional Economic Development Council Initiative and the Upstate Revitalization Initiative.

In both of these initiatives, development funds are allocated to New York’s ten regions through a process of competitive applications. From the former’s website:

This year, the 10 Regional Councils once again competed for funding and assistance from up to $750 million in state economic development resources as part of Round V of the REDC competition. Additionally, the Governor established a new competition in 2015 – the Upstate Revitalization Initiative – to award a total of $1.5 billion to three regions, which will help to transform local economies by providing $500 million over the next five years to support projects and strategies that create jobs, strengthen and diversify economies, and generate economic opportunity within the region. Of the state’s 10 regions, seven were eligible for the URI competition: Finger Lakes, Southern Tier, Central New York, Mohawk Valley, North Country, Capital District, and Mid-Hudson.

A quick scan of the dollars awarded in these initiatives shows that many, though not all, are earmarked for marginal improvements or investments and are unlikely to lead to large economic returns.

The Inevitable

If this was the only problem with dirigisme, we might simply lament it as a well-intentioned but wasteful approach to economic growth. However, it is usually accompanied by an increase in cronyism and corruption. The fact that the state has been collecting a tax surplus in the City and diverting it Upstate created an opportunity for administrators to play favorites in awarding contracts and to contravene the rules of competition that usually prevail in a free market. When this kind of opportunity emerges, it is inevitable that someone will seize on it.

And so the scandal that has just broken with the charging of nine people in Governor Cuomo’s entourage should not come as a surprise. City Journal takes a similar view:

Eager to revive the depressed counties of New York’s heartland and Southern Tier, Cuomo lacked the courage to use his considerable influence with the Albany legislature to prune taxes and pare regulation. His solution was to bury the problem in tax dollars. This approach isn’t intrinsically criminal, but it does attract people of low degree, some of whom have recently been posting bail. And it betrays poor judgment on Cuomo’s part—in the policies he pursues, in the people he trusts, and in the electorate at large.

The New York Post is equally skeptical of government-orchestrated public-private investments:

The cloud of alleged corruption now surrounding billions of dollars in state economic development investments is an outgrowth of Cuomo’s highly secretive and centralized management style.

Compared to previous Albany-directed corporate-welfare binges, Cuomo’s approach has featured a uniquely close intertwining of government and corporate interests — complete with state ownership of the means of production.

To an outside observer, it may have seemed curious that development of a solar-panel factory in Buffalo [the case being investigated] was being guided by a state college administrator in Albany.

This free market distortion is primarily systemic at its root. It grows naturally from the state’s involvement in the economy. As noted by City Journal, bad systems have a way of empowering bad actors. It is likely therefore that more revelations will surface about more malpractice elsewhere in the state’s initiatives.

Now would be a good time to re-evaluate the overriding economic strategy. So far, the state’s initiatives have weighed in favor of a top-down set of targeted solutions instead of a blanket laissez-faire approach that would foster growth from genuine grassroots entrepreneurship. But this experiment with dirigisme has led to the usual distortions of cronyism and wasted or misallocated resources. The state should consider stepping back from its deeper involvement and instead moving forward with lower tax rates for middle-income households and with lower regulation for businesses.

New York City’s high paying jobs generate the tax receipts needed to meet spending needs in the rest of the state. But the surplus from City tax revenues can also be seen as the enabler of bad policy and as the reason why the state has not implemented the fiscal policies needed Upstate. The City is a huge asset for the state but it may be holding back the measures needed to reignite a demographic and economic revival in all of New York.

This at least could be the conclusion drawn when we look back from the future at our present predicament. But so far, the Governor has shown no inclination of changing course, stating after the charges surfaced:

I am more committed to western New York’s revitalization than ever before… We are not going to miss a beat.

Note: The dependency ratio in the tables is calculated as the sum of people aged less than eighteen and more than 65, divided by the number of people aged 18-65.

This piece first appeared at Populyst.net.

Sami Karam is the founder and editor of populyst.net and the creator of the populyst index™. populyst is about innovation, demography and society. Before populyst, he was the founder and manager of the Seven Global funds and a fund manager at leading asset managers in Boston and New York. In addition to a finance MBA from the Wharton School, he holds a Master’s in Civil Engineering from Cornell and a Bachelor of Architecture from UT Austin.