When we look at how the U.S. economy is performing, we usually focus on the largest metropolitan areas. But some 29% of non-farm jobs in the U.S. are in small and midsize metro areas. And since they tend to be less economically diverse and more volatile, these metro areas often are where we can more clearly see the fissures in the economy — the sectors that are growing, and which are shrinking.

In this year’s edition of our Best Cities For Jobs survey, 13 of the 20 metro areas with the fastest job growth are small (under 150,000 total nonfarm jobs) and medium-sized (between 150,000 and 450,000 total nonfarm jobs).

Many of the smaller places creating jobs at the fastest pace are located in booming regions like the Intermountain West, near college towns and in regions with attractive natural amenities. Meanwhile, times are turning tougher in West Texas and other energy-dependent areas.

The winners and losers also reflect demographic trends, notably the tsunami of downshifting boomers, that will shape our society and economy for years to come.

The Utah Superstars

As is the case with larger areas, it usually helps if a smaller region has more than one economic pillar. This is certainly true for our No. 1 city overall, St. George, Utah. The job count in this metro area has grown a remarkable 32 percent since 2010. Last year St. George’s job growth rate was 7 percent, roughly 3.5 times faster than the national rate, and one reason the area leaped 30 places in our overall rankings from last year.

Located in the scenic southwestern part of the state near the Arizona border, and a magnet for retirees and tourists, St. George has had a remarkable population boom, growing from fewer than 100,000 residents in 2000 to 155,600 people as of 2015.

This demographic surge can be seen where you would expect it, with rapid growth in construction sector jobs – up over 50 percent since 2010 — as well as leisure and hospitality, where employment expanded 37.8 percent over the same span.

Yet this is not just a sleepy retirement and tourist town. The metro area has a median age of 32, three years older than the Utah average, but well below the national average of 37.2. Despite this younger demographic, job growth has occurred in sectors that tend to employ older workers, such as manufacturing, up 40.9 percent since 2010, and professional business services, up 34.6 percent.

Not surprisingly if you want to find other local economies that reflect this kind of dynamic, the best place to look is elsewhere in the Beehive State. Our second-ranked area nationally, Provo-Orem has also achieved rapid job growth, with employment expanding 27.4 percent since 2010. Like St. George, this metro area has enjoyed strong growth in construction and hospitality, but also in higher-wage fields, including information, which has expanded employment 43.9 percent since 2010, and professional business services, up 34.3 percent.

Home to Brigham Young University, the Harvard of Mormondom, the metro area is among the youngest in the nation, largely due to large Mormon families. It’s also, according to Gallup, the most religious as well as one of the best educated: almost 40 percent of its population over 25 holds bachelor’s degrees and almost 5 percent have advanced degrees, just ahead of San Jose, Calif., and Nashville, Tenn.

Also placing highly from Utah is No. 15 Ogden-Clearfield, which rose 25 notches over last year. Employment has expanded 16.2 percent since 2010. Like St. George and Provo-Orem, this region has experienced strong expansion in its construction and hospitality sectors, but also boasts great economic diversity. Since 2010, manufacturing employment has grown 10.4 percent while professional business service jobs have expanded a healthy 31.3 percent.

The Amenity Regions

Of course, you don’t have to be a Latter Day Saint to have a successful small city. But it helps a great deal if you happen to be in a place that has standout natural and cultural amenities. This trend may be greatly enhanced by the movement of seniors, particularly affluent ones, to what may be called “amenity regions” throughout the country. Contrary to the urban mythology pressed by the mainstream media, Census data shows that seniors are not moving “back to the city” in great numbers but generally to smaller, less dense regions, if they move at all.

Being in a nice place, of course, is an asset for any city; after all, entrepreneurs and young families also like to live somewhere good times beckon. At the same time, some of these areas also benefit from a strong hospitality and second home market. Another critical advantage belongs to college towns which, by their very nature, usually offer more by way of arts, restaurants and entertainment than other places.

The highest ranked of these metro areas this year is Fayetteville-Springdale-Rogers, AR-MO, which comes in sixth on our overall list. It enjoys the benefits of being home to the University of Arkansas as well as close to the Ozark Mountains, one of the premier recreation areas in middle America. Since 2010, employment in the metro area has jumped 19.6 percent, or 40,000 jobs, with a 4.7 percent expansion last year. Like other top small cities, the areas has enjoyed strong growth in construction and hospitality jobs, up 37.2 percent since 2010, but also professional and business services, which expanded 38.2 percent over the same time period.

Some other of the fastest-growing areas metro are tourism and retirement destinations on the tech-rich West Coast. Five years ago, Napa, Calif., and Bend-Redmond, Wash., were mired toward the bottom of our ranking in 344th and 36rd place, respectively. But as the coastal tech economies have surged, so have they, rising to 13th and 14th place this year. Hospitality and construction have been the big job gainers for both, with some jobs added in professional services as well.

Losing Ground In The Oil Patch

As tech-linked areas ascend, many energy-producing towns are slipping, with oil and gas prices in the dumps and the coal industry racked by the government-guided transition to cleaner forms of power production.

West Virginia’s metropolitan areas have all suffered major declines on our list, with Wheeling dropping 54 places from last year’s survey to 396th on a 0.7 percent contraction in employment on the year. In Charleston, W.V., which has fallen to five spots from the bottom of our list, mining and natural resources employment declined 9.8 percent last year and is off 31.5 percent since 2010. Big job losses have occurred also in Wyoming, a major coal producing area, where Cheyenne dropped 82 places to 206th as mining and natural resources employment contracted 6.2 percent last year.

Many once red-hot areas in the oil patch have taken devastating hits. Former high-flyer Victoria, Texas, dropped from 24th place last year to 115th. But no place reflects the flagging fortunes of the West Texas energy economy more than Midland, which, just last year ranked first on our list; this year it’s at 139th after losing 14.7 percent of its natural resources jobs and 6.9 percent of its jobs overall. Odessa fell from third last year to 173rd this year on the back of an 8.8 percent contraction in employment, and 20.4 percent in the natural resources sector.

Several Louisiana metro areas have suffered steep job losses, including Houma-Thibodaux, down 183 places on our list to 325th after an 8 percent contraction in employment. Several smaller Oklahoma communities have taken serious hits, including Tulsa, which dropped to 222nd. Bismarck, N.D., a prime beneficiary of the Bakken oil boom, dropped 67 places from last year to 102nd as 6.8 percent of its natural resources jobs evaporated, while Bakersfield, Calif., one of the country’s largest oil producing areas dropped 70 places to 109th as natural resources employment contracted 11.5 percent.

The Rust Belt: Is The Bounce Back Over?

The picture is less uniform in the industrial sector than in energy. Some manufacturing-oriented areas are booming, such as No. 4 Gainesville, Ga., and No. 10 Columbus, Ind., home to Cummins. Nationwide manufacturing employment grew a paltry 0.3 percent last year, with some local declines that devastated the affected economies.

In the Midwest, the big losers include Midland, Mich., which dropped 75 places to 245th, Green Bay, Wisc., which fell 83 places to 286th, and Fond du Lac, Wisc., which lost 173 places to 293rd. In Pennsylvania, Scranton-Wilkes Barre-Hazelton fell 97 places to 373rd and Williamsport dropped an astounding 212 places since last year to 383rd, with manufacturing employment off 13.2 percent since 2010 and overall employment down 3.5% last year. And then there’s Johnson, Pa., in last place at 421st.

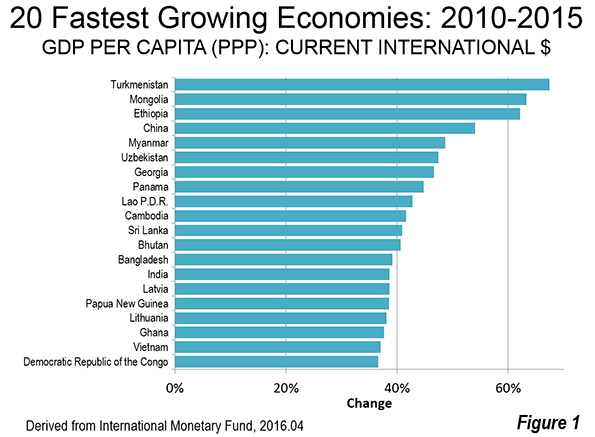

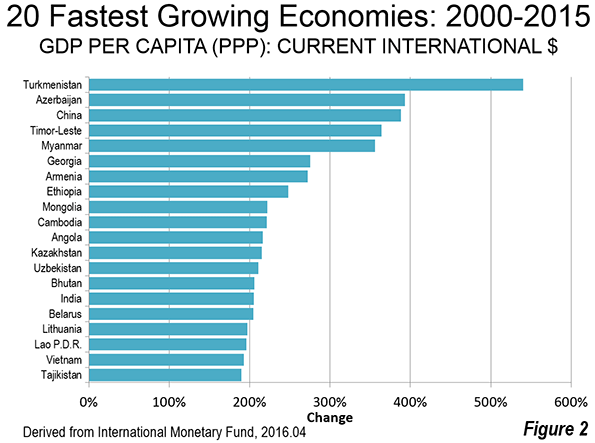

Like the energy economies, the industrially oriented metro areas are likely to stagnate for the time being as declines in global markets, the high dollar as well as lower demand from the energy sector take their toll. The International Monetary Fund predicts a modest 3.2 percent global growth rate for 2016, held down in significant part by a faltering Chinese economy. At the same time, OPEC overproduction and the addition of Iranian oil to global markets will likely keep the price below the $70-$80 per barrel range that energy producers need to start expanding energy investments again.

This means, for the time being at least, the strongest smaller cities will be those which attract people and companies from bigger places by offering better amenities, cheaper housing, better schools, growing populations and, in many cases, college campuses—all offering a better quality of life but in a smaller, usually more affordable place.

This piece first appeared at Forbes.

Joel Kotkin is executive editor of NewGeography.com. He is the Roger Hobbs Distinguished Fellow in Urban Studies at Chapman University and executive director of the Houston-based Center for Opportunity Urbanism. His newest book, The Human City: Urbanism for the rest of us, will be published in April by Agate. He is also author of The New Class Conflict, The City: A Global History, and The Next Hundred Million: America in 2050. He lives in Orange County, CA.

Michael Shires, Ph.D. is a professor at Pepperdine University School of Public Policy.

By UtahStizzle (Own work) [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons