This essay is part of a new report from the Center for Opportunity Urbanism called “America’s Housing Crisis.” The report contains several essays about the future of housing from various perspectives. Follow this link to download the full report (pdf).

The public’s preference and the views of the social and intellectual elite has never been greater.

Journalists, urban and environmental activists and politicians tend to share a vision of a future in which generations-old trends toward the decentralization and dispersal of both production and population are reversed. In this view, densification will replace sprawl, and mass transit will grow in importance relative to personal automobile use, as Americans in growing numbers abandon suburban houses for smaller apartments and condos in mid- density and high-density cities.

“The New American Dream is Living in a City, Not Owning a House in the Suburbs,” Time recently declared. The Atlantic agrees: “More Americans Moving to Cities, Reversing the Suburban Exodus.” As for the preferred housing type, the Smithsonian informs us: “Micro Apartments are the Future of Urban Living.” In this world-view, even farming will be brought “back to the city” with the emergence of vertical urban farms. “The Future of Agriculture May be Up” according to The Wall Street Journal. National Geographic predicts that “we may soon be munching on skyscraper scallions and avenue arugula.”

In this dense city-centric world view, not only will cities feed themselves—in reality a practical and economic impossibility—but also there’s virtually nothing density cannot do, from calming the climate to raising (U.S. national productivity. “Double a city’s population and its productivity goes up 130 percent” asserts MIT News.

In the depopulated hinterland between downtowns, sleek high-speed trains will whiz past rows of elegant white windmills or gleaming solar panels. Economies of scale and large- scale manufacturing will be replaced by high-tech localism and the rebirth of walkable dense neighborhoods.

Each wave of technological innovation since the early industrial revolution has inspired hopes that an economy of small-scale producers and small local markets and walkable, village- like communities can be preserved or recreated, using the most advanced technology available at the time. In 1812, in a letter to General Thaddeus Kosciusko, Thomas Jefferson wrote of his hope that industrial technology could be reconciled with a society of small farmers: “We have reduced the large and expensive machinery for most things to the compass of a private family, and every family of any size is now getting machines on a small scale for their household purposes.” In the early years of the twentieth century, Lewis Mumford hoped that electrification would permit a reversal of the trends toward large- scale corporations and utilities and infrastructure grids and a renaissance of community life and pedestrian cities.

The third industrial revolution based on information technology has produced its own variants of this utopia, with Alvin and Heidi Toffler predicting “the electronic cottage.” With these earlier utopias, today’s techno-urbanism shares the same social ideal, a society in which production and population are reconcentrated and re-localized in dense communities, which may take the form of the low-rise pedestrian cities of the New Urbanists or Green and “sustainable” skyscraper downtowns. The persistence of this vision, in ever-changing forms, suggests that its appeal must be explained in terms of nostalgia for the less far- flung, less centralized, smaller-scale communities of the agrarian era and the early industrial period.

Something like this vision of the future American landscape has achieved the status of a near-consensus in the mainstream press about the alleged return to the city and the impending demise of the suburbs. But the story is wrong in every detail. In reality, the American people are not abandoning low-density housing for crowded and expensive urban cores, nor are they likely to do so in the future.

In fact, the immediate and likely mid-term future will look, in many ways, much like the recent past. Factories, farms and office parks will continue to be dispersed through suburbs, exurbs and the countryside. Information technology will consume ever more electricity, most of which, for the foreseeable future, will come from conventional utilities using fossil fuels, not from renewables like wind and solar power. The aging of the population and the growth of low- paying personal service jobs will increase the importance to the service-sector working class of personal automobile use in employment. Self-driving cars and trucks, along with telecommuting, may reinforce this trend and produce further decentralization of work, housing, shopping and recreation. The robocar, not the passenger train, should be the icon of the transportation future.

TECHNOLOGY AND DECENTRALIZATION

For generations, successive technologies have dispersed production and population even as they have radically reduced transportation, energy and land costs. The increasing speed and flexibility permitted by innovative modes of transportation, from the canal to the railroad to the automobile, truck and airplane, have slashed freight and commuter costs while allowing production facilities and residences to spread out. The decentralization of work, shopping and dwelling has been enabled by the long distance transmission of energy and increasingly cheap, sophisticated and reliable telecommunications grids.

Since the beginning of the industrial era, each new form of travel—the train, the automobile or truck and the airplane—has permitted higher speeds. From 1800 to the present, personal mobility in the U.S. has grown at an average of 2.7 percent per year with a doubling time of 25 years. Higher speeds allow longer commutes or business trips in the same amount of time. This has resulted in the expansion of urban areas to take advantage of cheaper land for the kind of housing people prefer, largely single family, and the simultaneous decline in their overall density. One study notes that the automobile has allowed cities to grow as much as fifty times larger than the typical pre-modern pedestrian city, which was limited to an area of 20 square kilometers. Today’s advocates of urban “densification” frequently denounce the automobile as the source of so-called “sprawl.” But the trend toward urban deconcentration began with the first industrial revolution, based on steam power. Rather than build urban mass transit around smoke-spewing locomotives, many cities built horse-car lines, something which was not practical until industrial technology made iron or steel rails cheap. In many places these were later replaced by electric trolleys or subways (early horse-drawn railways using wooden tracks had been limited to mines). The growth of suburbs began with horse-drawn omnibuses, trolleys, subways and commuter rail. The “pedestrian cities” of 1900, idealized by many of today’s urban planners, in fact were more dispersed than compact pre-industrial villages and cities.

Nor has it ever been the case in the industrial era that production facilities have been situated for the convenience of existing city residents, as an alternative to moving workers to production sites. Mills grew up first along the fall lines of streams and rivers, where falling water could be tapped for energy. When coal-powered steam engines replaced waterpower, factory towns tended to be located near coal seams, as in the British Midlands, the Ruhr, and Pittsburgh, or else along rivers or canals with access to barge-borne coal. Mill towns and factory towns alike tended to grow up around the production facilities, which began as “greenfield” sites, to use modern terminology.

The second industrial revolution, based on the electric motor and the internal combustion engine, accelerated the decentralization of manufacturing in the U.S. and other advanced industrial countries. Electric wiring and motorized power tools allowed large, flat, horizontal factories to replace earlier vertical factories in which waterwheels or steam engines had driven machinery on multiple floors by means of ropes and pulleys. To save money, the new factories were located on cheap land, which only later became dense as residences and

amenities for workers grew up around them, as in Detroit. Trucks enabled factories to be located far from both waterways and rail lines, and personal car ownership allowed workers to live in less crowded conditions at greater distances from where they worked.

Paradoxically, passenger air travel, by creating truly national corporations on a continental scale whose facilities could be visited by managers in a single day, allowed the centralization of functions in high-rise office buildings in a few headquarters cities, like New York City, and to a lesser extent, Chicago and, more recently, Los Angeles, Houston, Dallas and Atlanta. Satellite technology and the worldwide Web have enabled the further centralization of supervision over multinational corporations and global supply chains. The error of all too many modern urbanists is a failure to understand that the managerial and financial functions of such dense urban cores depend for their existence on supply chains and consumer markets in lower- density areas across the United States and the world. Only a small number of cities can specialize in these functions in the national and world economies, and these “global cities” like New York and Tokyo and Frankfurt cannot serve as models for most metro areas.

THE FUTURE OF PRODUCTION

Will the trend toward the decentralization of production and housing be reversed in the twenty-first century?

Although their contribution to national employment is dwindling because of automation and offshoring, traded sector industries such as manufacturing, energy, mining and agriculture remain important parts of an advanced economy, because of their multiplier effects and upstream and downstream linkages. According to the Bureau of Economic Analysis, every dollar in final sales of a manufactured good is responsible for $1.34 in input from other economic sectors, while a dollar of retail trade generates only 55 cents and a dollar of wholesale trade only 58 cents. These industries, by their nature, tend to locate their facilities in low-density areas and need extensive, state-of-the-art infrastructures to connect them with national and global suppliers and businesses and consumer markets with minimum friction and cost.

The decentralization enabled by trucks and cars and buses has converted the monocentric city of the railroad and canal era into what William Bogart, following Jean Gottmann, has called the polycentric city—a blob-like metro area with multiple smaller retail, office and recreation centers. For a while some older urban cores became specialized downtown business districts, housing the headquarters of firms whose factories, warehouses or back offices were located where land or labor or both were cheaper, in suburbs, small towns, and other states or other countries. But as headquarters have moved to suburban office parks and exurban campuses, many downtowns have reinvented themselves again as “playground cities” based around amenities enjoyed by a residential population of the rich and young professionals before marriage, as well as transient populations of tourists.

Production has moved back to its historic home, the countryside or the outskirts of town. The migration of production out of the city has been accelerated by municipal policies that penalize productive enterprises because of their side effects of traffic, waste or pollution. The real estate

interest in gentrification—turning former warehouses into lofts for affluent members of the gentry class or restaurants or offices for fashionable social media startups—has seized on this transformation, and in some places, with favorable economic results.

The mainstream press frequently publishes breathless articles about the alleged rise of urban agriculture— sometimes accompanied by striking illustrations of skyscrapers full of hydroponic gardens or covered with what appears to be kudzu. Most of these stories quote a single activist, Dickson Despommier, a retired professor of microbiology at Columbia University’s School of Public Health. Many articles convey Despommier’s claims about the alleged superiority of indoor, climate- controlled farming in big cities without raising any objections.

The most obvious objection is the price of land. Even if greenhouses and, in time, synthetic food laboratories were to contribute more to the diet of people in advanced industrial nations like the U.S., and even if consumers insisted on fresh food from nearby, most of these structures would be located on the periphery of expensive cities in low-rise suburbs or exurbs, to minimize the contribution of rent to the price. No matter what technology might be used, food grown in Manhattan will always be an expensive luxury because of land rent alone.

Nor is most manufacturing ever likely to return to densely-populated, expensive urban areas. The automation of factories is reducing the manufacturing workforce worldwide, even in China. As labor costs decline in importance as a factor in location, more firms may choose to site increasingly-robotic factories near consumer markets and supply chains. And rapid prototyping and other advances that enable customization and short production runs may reduce the benefit that large factories enjoy over smaller operations.

But high-tech home production of most appliances and high-tech versions of the village blacksmith will probably remain in the realm of science fiction. Economies of scale will probably continue to characterize even advanced manufacturing, to some degree. Most important of all, high rents, combined with municipal regulations, will make cities unattractive as sites for major factories, as distinct from small-scale artisanal shops. Neither agriculture nor large-scale manufacturing are likely to return to cities with high rents and property prices.

BERMUDA TRIANGLE URBANISM

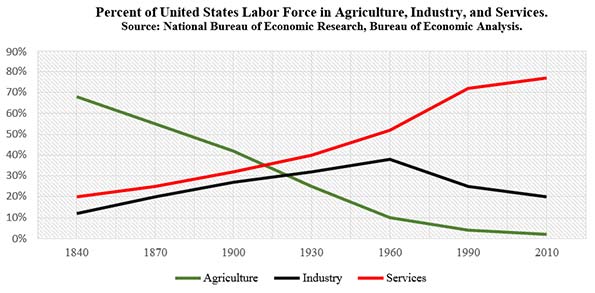

What about service sector jobs? As automation leads manufacturing and other productive sectors to shed labor, the greatest growth in absolute employment is found in domestic service sector jobs in health, education, retail, government and other industries that cannot easily be outsourced or automated. The Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) projects that in 2022 “services-providing” jobs will account for 80.9 percent of new U.S. jobs.

According to one influential view, the “new economy” is a post-material “knowledge economy” or “information economy” in which the production of immaterial goods and services is more important than material goods and traditional services. Adherents of this school often treat the most important activities in a modern economy as tech and financial services. This school of thought holds that U.S. productivity would be increased if more people were

added to a few U.S. metro areas that specialize in tech and finance, with help from “densification” policies such as transit-oriented development.

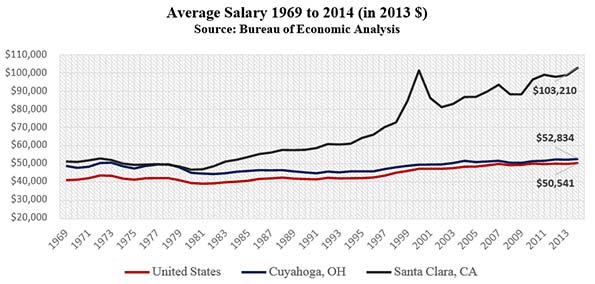

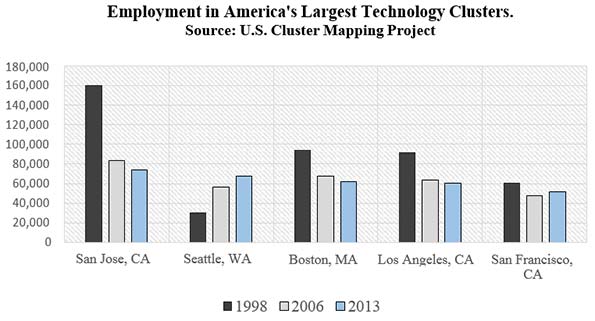

According to Chang Tai-Hsieh of the University of Chicago and Enrico Moretti of the University of California, Berkeley, the U.S. could be more productive if more workers could move from less productive cities to more productive cities, which they identify as, among others, San Francisco, San Jose, New York, Boston, and Seattle. They criticize land-use restrictions which prevent more high-rise apartments and high-rise office buildings to house the hordes who allegedly would boost their own productivity, and the nation’s as well, by moving from Bakersfield to San Jose. In short, massive densification would produce huge gains in productivity.

In all of this there is a grain of truth—but only a very small grain. It is true that, in certain industries, there are genuine agglomeration effects, leading to the dominance of one locale in that field, at least for a while: Silicon Valley for tech, Wall Street for finance, Detroit for automobiles, Hollywood for entertainment. These locations brought together workers, firms, capital, infrastructure and flourishing social networks facilitating the exchange of ideas. If you want to be a country music singer, it was a good idea to move from Tulsa, Oklahoma to Nashville in the old days and to Branson today.

But even these productivity effects are limited to particular industries with particular skill sets. You are more likely to improve your productivity and success as a country music singer if you move from Tulsa to Branson—but not if you move from Tulsa to Silicon Valley or Wall Street. Moretti and Hsieh admit: “The assumption of inter-industry mobility is clearly false in the short run. For example,

it would be hard to relocate a Detroit car manufacturing worker to a San Francisco high tech firm overnight. On the other hand, the assumption is more plausible in the long run, as workers skills—especially the skills of new workers entering the labor market—can adjust."

In spite of this concession to reality, Moretti and Hsieh argue for the mass relocation of much of the U.S. workforce to San Francisco, San Jose, New York and a few other big cities. As Timothy B. Lee notes in Vox:

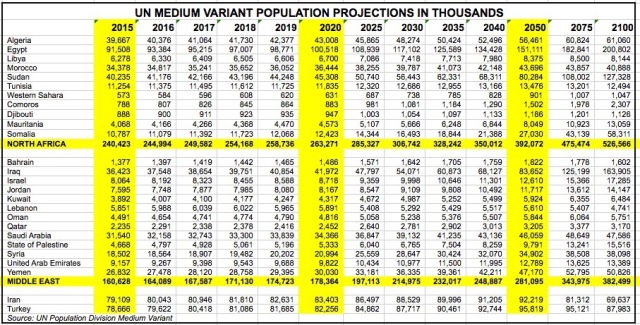

Hsieh and Moretti envision the New York metropolitan area becoming 9 times its current size, meaning that more than half the country would live there. The Austin metropolitan area would quadruple in size, as would the San Francisco Bay Area. Half the cities in America would lose 80 percent or more of their population. The population of Flint, MI, would shrink from 102,000 people to fewer than 2000.

This might be called Bermuda Triangle urbanism. Certain metro areas are like the Bermuda Triangle and other legendary zones in which the laws of nature are supposed to operate differently than everywhere else. These metro areas have the unique property of magically raising the productivity of human beings of all skill sets who cross an invisible force field into them.

Hsieh and Moretti argue that their favored coastal metro areas could rival Southern metro areas in growth by adopting the less restrictive land policies characteristic of growing Southern and Southwestern cities:

We find that three quarters of aggregate U.S. growth between 1964 and 2009 was due to growth

in Southern US cites and a group of 19 other cities. Although labor productivity and labor demand grew most rapidly in New York, San Francisco, and San Jose thanks to a concentration of human capital intensive industries like high tech and finance, growth in these three cities had limited benefits for the U.S. as a whole. The reason is that the main effect of the fast productivity growth in New York, San Francisco, and San Jose was an increase in local housing prices and local wages, not in employment. In the presence of strong labor demand, tight housing supply constraints effectively limited employment growth in these cities. In contrast, the housing supply was relatively elastic in Southern cities.Therefore, TFP growth in these cities had a modest effect on housing prices and wages and a large effect on local employment.

Advocates of “densification” have seized on Hsieh’s and Moretti’s work to argue for crowding more people into San Francisco and Manhattan by adding skyscrapers, legalizing micro-apartments and squeezing tiny houses into existing suburbs.xxvii But this ignores the fact that the growth of Southern and Southwestern cities has been driven in large part by the desire of middle-class and working-class Americans, as well as affluent Americans, to spend less while enjoying bigger homes and yards. According to demographer Wendell Cox, Census data shows that of the 51 metropolitan areas with more than 1 million residents, only three—Boston, Providence, and Oklahoma City—saw their core cities grow faster than their suburbs. (And both Boston and Providence grew slowly; their suburbs just grew more slowly. Oklahoma City, meanwhile, built suburban residences on the plentiful undeveloped land within city limits.)”. Similar preferences manifestly exist among younger generations of Americans. Between 2000–2011, the number of Americans aged 20–29 increased twenty times as much as the increase of their cohort in central business districts. To accommodate this desire for inexpensive space Southern and Southwestern cities have expanded horizontally, not vertically.

To their credit, Hsieh and Moretti acknowledge that transportation systems, by enabling longer commutes, can allow more people to live in a metro area that remains relatively low in density. But even here they play to the prejudices of the coastal and campus intelligentsia, by endorsing high-speed rail: “An alternative is the development of public transportation that link local labor markets characterized by high productivity and high nominal wages to local labor markets characterized by low nominal wages. For example, a possible benefit of high speed train currently under construction in California is to connect low-wage cities in California’s Central Valley—Sacramento, Stockton, Modesto, Fresno—to high productivity jobs in the San Francisco Bay Area.”

Hsieh and Moretti ignore how high-growth Southern cities—their putative models—actually grew. Cities in the South and Southwest in the last half century have expanded thanks to cars and trucks on adequate systems of streets and highways, and near-universal personal automobile ownership, not on the basis of a pre-automobile infrastructure of trains and trolleys and subways. People have moved there—and this appears to be true of educated workers—precisely not to live in high density and expensive areas.

The link between densification and productivity does not exist even in the so-called “knowledge economy” of the tech sector. Even the intellectual labor of R&D tends to be done in the low-density environments of university and corporate campuses like those of Silicon Valley, Austin and the Research Triangle. The expensive downtowns of skyscraper cities increasingly are home to rentiers with residual financial claims on the products of innovation, including investors and former innovators, rather than individuals and groups engaged in important technological innovation themselves.

THE NEW LANDSCAPE OF EMPLOYMENT

Access to cars for personal use will become more, not less, important for the majority of the American workforce in the decades ahead, thanks to the shifting composition of the workforce and the spatial deconcentration of service sector jobs. While better-paying service sector jobs like those in finance, law and business and professional services may remain downtown in corporate headquarters, an increasing number of lower-wage jobs involving personal care will be found in lower-rent suburbs and exurbs within metro areas. Particularly important among these will be jobs caring for the elderly, either at hospitals and medical centers and nursing homes, or in the homes of the elderly themselves. Between 2002 and 2022, health care and social assistance will have created more jobs than any other sector, growing from 9.5 percent of employment to 13.6 percent.

Overwhelming numbers of American seniors say they wish to stay in their homes as long as they can. Given the expense of residenial care, elderly Americans will try to remain home with the help not only of technology but also of personal services provided in their homes. These services, many of them paying modestly, will provide employment for nurses, health aides, food delivers, shoppers, drivers, and others providing in-home care or help. Because their clients will be dispersed through metro areas, personal vehicle ownership or access to a car will be a necessity for most of these in-home care-givers. And because few of these jobs are likely to pay well, members of the new service sector working class will economize on expenditures by living in low-cost neighborhoods and shopping at discount stores and dining in affordable restaurants that are located in low- density areas and do not pass on high rents to their customers.

What we are witnessing is the emergence of something not too dissimilar to European cities with gentrified downtowns becoming centers of high-status spending and employment while poverty is decentralized through the suburbs, particularly those in the inner ring while newer suburbs and exurbs generally do better.xxxiv This reversal of the mid-twentieth century pattern of downtown poverty and suburban affluence poses particular challenges to low-income workers without access to cars in suburbs and exurbs. Researchers at the Brookings Institute, studying data from hundreds of transit providers in numerous metro areas, discovered that, on average, workers reliant on mass transit cannot reach 70 percent of the jobs in their area in less than 90 minutes. Workers in low-income suburbs were even worse off. Only 22 percent of potential metro area jobs for which they were eligible were accessible in less than an hour and a half one way by means of mass transit.

According to a study of two federal pilot programs operated by the Department of Housing and Urban Development, Moving to Opportunity for Fair Housing and Welfare to Work vouchers, poor participants with cars lived in better neighborhoods and greater employment opportunities. Low-income workers who received Moving to Opportunity Vouchers were twice as likely to get jobs and four times as likely to stay employed. Even when mass transit is available it tends to consume more time than commuting by car. Another study, showing the superior outcomes available to poor people with access to private vehicles, concluded: “If we were most interested in increasing the mobility of the poor, we would subsidize car ownership.”

ROBOCARS VS. RAILROADS

In his 2011 State of the Union address, President Barack Obama declared: “Within 25 years, our goal is to give 80 percent of Americans access to high-speed rail. This could allow you to go places in half the time it takes to travel by car. For some trips, it will be faster than flying—without the pat-down.” This vision was encouraged by maps showing an imaginary continental network of high-speed passenger rail.

But the president’s high-speed rail initiative soon collided with reality. In 2011, the Obama administration proposed spending $53 billion on high- speed rail in the next six years. But from 2009-2014 the federal government has spent only $11 billion on high-speed rail. Governors in a number of states have blocked their states from accepting federal high-speed rail grants, for fear of escalating costs. California’s high speed rail project has been plagued by lawsuits and dwindling public support. Amtrak’s Acela, instead of travelling between New York and Washington in only 90 minutes as a true high-speed train might, takes nearly three hours to cover the distance. It would take a quarter century and an estimated expenditure of $150 billion to turn the Washington-to-New York route into a true high-speed rail route.

The fetishization by many opinion leaders of fixed-rail technology as a futuristic symbol is puzzling. Passenger trains, like passenger blimps, are an anachronistic technology. Most passenger rail in the U.S. was rendered obsolete by the development of automobiles and airlines in the last century. A nonstop cross-country flight in the U.S. usually takes no more than six or seven hours from airport to airport. Even if high- speed rail could compete on some routes, the number of destinations would be far smaller than those accessible by high- speed air. The displacement of passenger rail by air travel and automobile travel in the U.S. has led railroads to return to their original mission from the days of horse-drawn trams and canals—the efficient overland movement of freight.

The only part of the U.S. where inter-city passenger rail is significant is the Amtrak corridor through the Northeastern megalopolis from Washington, D.C. to Boston. But tickets are expensive, in spite of federal subsidies. In recent years, inter-city bus services have competed with Amtrak along its own route, with much cheaper tickets and only slightly longer travel time. Inter-city bus companies like Bolt have been able to lure away professional- class travelers with amenities superior to those that Amtrak offers for a fraction of the price. A 2013 comparison of Amtrak and bus service in a number of routes across the nation concluded that “the cost of providing scheduled motorcoach service is significantly lower than the cost of providing Amtrak train service. The cost difference ranges from a low of $17 per passenger (Washington, DC to Lynchburg, VA) to a high of more than $400 per passenger (San Antonio, TX to El Paso, TX).”

What about intra-city rail transit? Outside of a few dense urban areas like New York City, the future of fixed- rail seems bleak, notwithstanding the enthusiasm of urban planners for “light rail” transit projects, which have replaced skyscrapers and Seattle-style space needle towers as icons of progress and prestige in the imaginations of local boosters. As the technology of self-driving cars advances and regulatory systems adapt, the price of rides in robotaxis compared to subway fare will plummet because taxi fares need no longer support a human worker, only maintenance and energy costs and a modest profit. Single-mode, point-to-point travel will always be more flexible and efficient than fixed- rail transit which requires parts of the journey to be undertaken by foot, bicycle, or automobile, including taxi travel. In most American cities, buses and taxis and personal cars rendered trolley systems obsolete by the mid-twentieth century. By the mid-twenty-first century, except in a few cities or a few routes like airports to convention/hotel centers, robotaxis may put subways and light trail out of business.

Will robotaxis replace personal cars altogether? Many urbanist opponents of personal automobile ownership hope that fleets of robotaxis will roam the suburbs as well as dense urban centers, permitting suburbanites to dispense with garages and perhaps allowing “densification” of suburban neighborhoods, with houses built right up to the street. Like most fantasies of orthodox urbanism, this is unrealistic. Even if the costs of robotaxis fall radically, it is hard to imagine suburbanites repeatedly calling taxis during the day for different trips—to work and back, to drop off and pick up children and school, to go shopping and to go out to a restaurant for dinner. In the suburbs, if not in dense urban centers, garages are likely to remain—and they will house the family robocar.

What is more, the family robocar, like its human-operated predecessors— the station wagon and the minivan and the SUV—will be large enough to accommodate groups of people or large quantities of groceries or other purchases on occasion. And like today’s cars, it will be designed to operate both in cities and on highways. Visions in which individuals on a daily basis now choose tiny one-or-two passenger self-driving cars to commute and now rent spacious robot vans by the hour to go shopping are unlikely to be realized be realized if waiting times make it inconvenient to summon rental vehicles in low-density neighborhoods, as opposed to dense urban cores.

To the extent that the automation of automobiles and trucks reduces accidents, safety considerations as an incentive to purchase large, heavy vehicles may diminish, and there may be a trend toward somewhat lighter and smaller cars. Still, it is reasonable to predict that fully self-driving cars and trucks will broadly resemble today’s human-operated vehicles, if only because the spatial demands imposed by the dimensions of passengers and freight will remain the same. The street and highway infrastructure of tomorrow is also likely to be more or less the same for self-driving vehicles in the future as for today’s cars and trucks, although fixed signals like painted stripes may give way to virtual signals permitting more flexible road use.

Reflecting the anti-automobile bias of the gentry intelligentsia, the American press has trumpeted a recent finding that between 2007 and 2012 the number of households without a vehicle increased. But the increase was negligible, from 8.7 percent to 9.2 percent.xli Seventy-five percent of Americans drive to work, while ten percent commute to work by means of carpooling, a number that may have been enlarged by the hardships imposed by the Great Recession.

Personal care use may well expand, thanks to self-driving cars. The annual cost of upkeep of roads may increase, and it may be necessary to expand road capacity, if the automation of the automobile increases traffic by allowing the elderly and unescorted children to travel without having to drive or be driven by another person.

Flying as well as driving is on the verge of being transformed by robotics. The Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) may soon adopt regulations that permit the use of drones in the U.S. by civilian business.xliii The potential impact on industries and business models can only be imagined. Restaurant-to-door pizza delivery by drone is probably not in the cards any time soon. The most likely applications of commercial drones are in air freight transportation, warehousing, agriculture and photography, among other industries.

Meanwhile, increasing automation may make passenger air travel safer. It might also enable the rise of “air taxis”—small aircraft which can pick up passengers on a flexible basis, along the lines of the “free flight” envisioned by a recent NASA study.

ENERGY IN THE INFORMATION AGE: MYTH VS. REALITY

Like popular visions of a future American landscape based on urban density and mass transit, perceptions about the information technology and energy infrastructure of the future are equally at odds with reality.

The ICT (Information and Communications Technology) ecosystem is being transformed by a number of trends: the mobile internet, cloud computing, big data, the “internet of things” and “the industrial internet.” All of these trends together will translate into increased demand for both electricity and reliable wireless communications.

Because much of the infrastructure supporting ICT is not visible—fiber optic cable, remote data centers, wireless towers—it is easy for the users of modern technology to imagine that it consumes less energy and materials than old- fashioned appliances, and to believe that information-based industries somehow exist in cyberspace rather than the material world. But the alleged virtual reality of cyberspace is grounded in physical infrastructure.

Unlike windmills and high-speed trains, data centers are not part of the popular iconography of the imagined future. Indeed, for security reasons, many data centers are hidden from public view in nondescript buildings in remote complexes. The result, as a New York Times report notes, is the illusion that information exists in an immaterial world: “The complexity of a basic transaction is a mystery to most users: Sending a message with photographs to a neighbor could involve a trip through hundreds or thousands of miles of Internet conduits

and multiple data centers before the e-mail arrives across the street.”

In spite of their effective invisibility, data centers are the backbone of the digital economy. As these nodes in national and global communications networks grow in importance, they consume more energy. A modern data center uses 100 to 200 times more electricity per square foot than an office building.xlvi Some data centers consume as much energy as small towns. In 2013 U.S. data centers devoured enough kilowatt-hours of electricity—91 billion—to power twice the number of households in New York City.xlvii Gains in efficiency and productivity may be outstripped by increased demands made possible by falling prices.

And energy-hungry data centers themselves represent only 20 percent of ICT electric consumption, with the rest dispersed among hand-held devices, PC’s and other technologies. As one study notes, “Cost and availability of electricity for the cloud is dominated by same realities as for society at large—obtaining electricity at the highest availability and lowest possible cost."

Electricity to power increasingly sophisticated phones and computers and cloud computing centers as well as machine-to-machine communication and communication among self- driving vehicles will have to come from somewhere. Will the source be renewable energy? Many Americans have been persuaded that combating global warming will require a rapid—and relatively painless—transition from fossil fuels to renewables, identified in the popular imagination with wind power and solar energy. This vision is sometimes united with the idea of a “distributed” energy network, in which utilities buy

much of their electricity from rooftop solar panels or electric cars.

In reality, the reign of hydrocarbons in the energy mix is far from over. The U.S. Energy Information Administration predicts that in 2040 as much as 80 percent of primary energy consumption by fuel in the U.S. will originate with three fossil fuels—petroleum and other liquids (33 percent), natural gas (29 percent) and coal (18 percent). In their contribution to primary energy production, renewables are predicted to rise only from 8 percent in 2013 to 10 percent in 2040. As a share of electricity generation by fuel, renewables are predicted to account for only 15–22 percent in 2040, roughly the same as nuclear energy. Most of the renewable category is accounted for by hydropower and wind; only minor contributions will be made even in the best case scenarios for 2040 by solar, geothermal, and biomass.

FUTURE INFRASTRUCTURE: EVOLUTION, NOT REVOLUTION

The conventional wisdom of urban planners posits revolution, not evolution. It is widely assumed that the trend of decentralization of production, housing and shopping—a trend that has been reinforced by each new wave of technology, beginning with steam engines—will somehow be reversed in the near future, leading to the reconcentration not only of housing but also of much manufacturing and even “urban agriculture” in dense cities. And all of this is supposed to be accompanied by mass abandonment of personal automobile use for mass transit and a rapid transition from fossil fuels to renewable energy sources.

As I have sought to demonstrate, none of these assumptions is plausible.

The future American landscape will be characterized by evolution, not revolution. The desire to minimize costs will lead most businesses and households to avoid expensive, dense urban areas for low-density regions with cheaper land. According to Jed Kolko of Trulia, only one of the ten fastest-growing cities with more than 500,000 people, Seattle, is predominantly urban, while five—Austin, Fort Worth, Charlotte, San Antonio and Phoenix—are majority suburban.

Roads and highways will be important, as increasingly autonomous cars and trucks and buses render fixed-rail passenger transit even more marginal than it is today for passenger transportation (rail will retain its utility for freight transportation in the U.S.). Air travel will become more complex, with the addition to airliners of civilian drones and perhaps “air taxis” reshaping patterns of production, package delivery and commuting. Telecommuting and the gradual electrification of transport will make reliable electric grids all the more indispensable. And the displacement of coal by natural gas, and the evolution of a global market in natural gas, will necessitate more pipelines. Growing Internet usage will have to be matched by reliable high-speed connectivity via national and international grids and increasingly colossal data servers which, even if they are more efficient, will require immense quantities of energy for operation and cooling.

Far from reducing the quality of life of the working class/middle class majority in an aging America, “sprawl” or decentralization, if properly carried out, can benefit both the providers and consumers of personal services. Personal service providers with access to cars have a much greater market for their services— particularly if highways or expressways enlarge the number of sites or homes that they can visit. At the same time, low-cost, low-density housing in suburbs, exurbs and small-towns makes it easier for the elderly to age in place. Emergent technologies such as telemedicine and autonomous vehicles may make suburban life much less challenging for the elderly who can no longer drive. The greatest beneficiaries of an automobile-based service economy may be the low-income elderly and their modestly-paid caregivers.

This picture is at odds with the kind of urban futurism which envisions passenger trains whizzing past windmills and solar power panels on their way from one skyscraper metropolis to another. Certainly robocars, power lines, natural gas pipelines, and data centers are less striking and glamorous than fashionable icons of pop futurism like high-speed rail and imaginary farms inside skyscrapers. But a decentralized America built on the bones of high-capacity roads, power lines, pipelines, and airstrips can enjoy a growing economy while minimizing the de facto taxes imposed by congestion, high land prices, and other detritus of excessive density. The historic nexus among technology, decentralization and the quality of life, far from being rendered obsolete, is on the verge of being reinforced and renewed in the United States.

This essay is part of a new report from the Center for Opportunity Urbanism called “America’s Housing Crisis.” The report contains several essays about the future of housing from various perspectives. Follow this link to download the full report (pdf).

Michael Lind is the Policy Director of the Economic Growth Program at the New America Foundation in Washington, D.C., editor of New American Contract and its blog Value Added, and a columnist forSalon magazine. He is also the author of Land of Promise: An Economic History of the United States. Lind was a guest lecturer at Harvard Law School and has taught at Johns Hopkins and Virginia Tech. He has been an editor or staff writer at the New Yorker, Harper’s Magazine, the New Republic and the National Interest.