As its economy bounced back from the Great Recession, California emerged as a progressive role model, with New York Times columnist Paul Krugman arguing that the state’s “success” was proof of the superiority of a high tax, high regulation economy. Some have even embraced the notion that California should secede to form its own more perfect union.

Pumped up by all the love, California’s leaders have taken it upon themselves to act essentially as if they were running their own nation. In reaction to President Trump’s abandonment of the Paris accords, Gov. Jerry Brown trekked to Beijing to show climate solidarity with President Xi, whose country is by far the world’s largest greenhouse gas emitter and still burns coal at record rates, but mouths all the right climate rhetoric.

At the same time California’s Attorney General is spending millions to protect undocumented workers and there’s legislation being proposed to transform the entire place into a “sanctuary state.” Sacramento also recently banned travel by government workers to Texas and seven other states that fail to follow the California line on gay and transgender rights.

Past performance and future trajectory

When progressive journalists, including those in Texas, speak about the California model, they usually refer to the state’s economic performance since 2010, which has been well above the national average. Yet this may have been only an aberrant phenomenon. Since 2010, Texas’ job count has grown by 20.6 percent compared to 18.6 percent for California. If you pull the curtain even further, to 2000, however, the gap is even bigger, with employment growing 32.7 percent in Texas compared to 18 percent in California.

The main problem is that California’s once remarkably varied and vital economy has become dangerously dependent on the Bay Area tech boom. Since 2010, the Silicon Valley-San Jose economy and San Francisco have been on a tear, growing their employment base by 25 percent. Job growth in the rest of the state has been a more modest 15 percent. “It’s not a California miracle, but really should be called a Silicon Valley miracle,” notes Chapman University forecaster Jim Doti. “The rest of the state really isn’t doing well.”

Tech starts to slow

Such dependency poses dangers. The tech economy is very volatile, and now seems overdue for a major correction. People tend to forget the depth of the tech bust at the turn of the century. If you go back to 2000, San Jose’s job growth rate is among the lowest in the state, less than half the state average.

Now tech is clearly slowing – job growth in the information sector has slowed over the past year from almost 10 percent to under 2 percent. Particularly hard-hit is high-tech startup formation, down almost half in the first quarter from two years ago; the National Venture Capital Association reported that the number of deals in the quarter was the lowest since the third quarter of 2010.

The growing hegemony of a few very large firms – chiefly Apple, Google and Facebook — has created a very difficult environment for upstarts. As one recent paper demonstrates, these “super platforms” depress competition, squeeze suppliers and reduce opportunities for potential rivals, much as the monopolists of the late 19th century did.

And as we found in our recent survey of the hot spots for high wage professional business services jobs, last year’s growth rates for this critical middle class sector in Silicon Valley and San Francisco lagged considerably behind those of boomtowns such as Nashville, Dallas, Austin, Orlando, San Antonio, Salt Lake City and Charlotte. Most other California metro areas, including Los Angeles, have languished in the bottom half of the rankings. These trends suggest that the state’s job performance will at least drop to the national average over the next two years and perhaps below, says California Lutheran University forecaster Matthew Fienup.

Rising inequality

California is home to a large chunk of the world’s richest people and particularly dominates the list of billionaires under 40. Yet, by one new measure introduced by the Census Bureau last year, the state also suffers the nation’s highest poverty rate; while a 2015 United Way study found that close to one in three Californians were barely able to pay their bills. No surprise then that as of 2015, the state was the most unequal in the nation, according to the Social Science Research Council.

As of 2011, nearly half of the 16 counties with the highest percentages of people earning over $190,000 annually were located in California but denizens of the state’s interior have done far worse. A 2015 report found California was home to a remarkable 77 of the country’s 297 most “economically challenged,” cities based on levels of poverty and employment. Altogether these cities had a population of more than 12 million in 2010, roughly one third of the state at the time. Six of the ten metropolitan areas in the country with the highest percentage of jobless are located in the central and eastern parts of the state.

What is disappearing faster than any state, according to a survey last year, is California’s middle class, a pattern also seen in a recent Pew study. One clear sign of middle class decline: California’s homeownership rates now rank among the lowest in the nation and Los Angeles-Orange County, the state’s largest metropolitan area, suffers the lowest level of homeownership of any major region.

Jerry’s Jihad and its consequences

State policies tied to Jerry Brown’s climate jihad have widened these divides. Inland Empire economist John Husing asserts that Brown has placed California “at war“ with blue-collar industries like home building, energy, agriculture and manufacturing. These jobs are critical for regions where almost half the workforce has a high school education or less.

Richard Chapman, President and CEO of the economic development arm of Kern County, an area dependent on these industries, complains that most polices promulgated in Sacramento — from water and energy regulations to the embrace of sanctuary status and a $15 an hour minimum wage — give little consideration given to the needs of the interior. “We don’t have seats at the table,” he laments. “We are a flyover state within a state.”

The recent legislation to raise the minimum wage to $15 an hour will have more severe ramifications for less affluent areas than San Francisco. As for climate policies, the state no longer even assesses the economic implications. Yet the state’s costly renewable energy mandates make a lot of difference in the less temperate interior when energy prices are 50 percent rise above neighboring states. A recent study found that the average summer electric bill in rich, liberal and temperate Marin County was $250 a month, while in the impoverished, hotter Central Valley communities, where air conditioners are a necessity, the average bill was twice as high. Some one million Californians, many in the state’s hotter interior, were driven into “energy poverty,” a 2012 Manhattan Institute study stated.

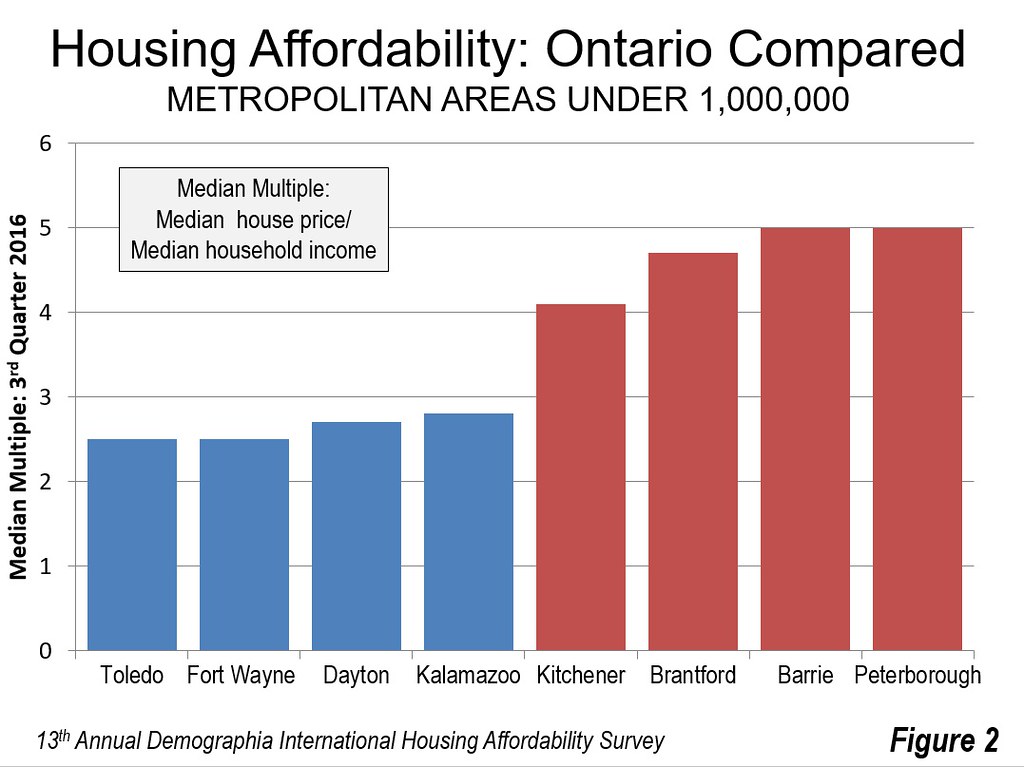

Housing has arguably emerged as the biggest force accentuating inequality. Environmental restrictions that have cramped home production of all kinds, particularly the building of affordable single-family homes on the periphery. The ever increasing restrictions have made the state among the most unaffordable in the nation, driving homeownership rates to the lowest levels since the 1940s. New “zero emissions” housing policies alone are likely to boost the already bloated cost of new construction by tens of thousands of dollars per home.

Demographic crisis looms

In much of California, particularly along the south coast, the number of children has dropped sharply. Since 2000, there has been a precipitous 13.6 percent drop in the number of residents under 17 in Los Angeles, while that number has remained flat in the Bay Area. In contrast, there has been 20 percent growth or better in the under 17 population in more affordable metropolitan areas such as Dallas-Fort Worth, Atlanta, Charlotte, Raleigh, Phoenix and San Antonio.

Housing prices, in part driven by state and regional regulation, are gradually sending the seed corn — younger workers — to more affordable places. Despite claims that people leaving California are old and poor, the two most recent year’s data from the IRS shows larger net losses of people in the 35 to 54 age group. Losses were particularly marked among those making between $100,000 and $200,000 annually.

Young people particularly are on the way out. California boomers, as we discussed in a recent Chapman University report, have a homeownership rate around the national average but the state has the third lowest home ownership rate in the nation for people 25 to 34, behind just New York and Washington. The drop among this demographic in San Jose and the Los Angeles areas since 1990 are roughly twice the national average and a recent San Jose Mercury News poll found nearly half of all Bay Area millennials planning to move, mostly motivated by housing and costs. The one population on the upswing in the state are seniors, particularly in the coastal countries, who bought their homes when they were much less expensive.

As long as home prices stay high, and opportunities for high-wage employment highly limited, the state will continue to suffer net domestic migration outflows, as it has for the last 22 of the past 25 years. Given that the state’s birthrate is also at a historic low and immigration from abroad has slowed, there’s a looming shortage of new workers. Between 2013 and 2025 the number of California high school graduates is expected to drop by 5 percent compared to a 19 percent increase in Texas, 10 percent growth in Florida and a 9 percent increase in North Carolina.

And for what?

Of course, many environmental activists generally prefer smaller families to cut greenhouse gas emissions; smaller families also serve the needs of developers of high-density housing, who might prefer that younger people remain long-term adolescents.

Sadly, many of these climate policies, which cause so much damage, won’t have much of an impact on the actual climate unless the rest of the country adopts similar measures. This stems from the state’s already low carbon footprint and the impact of people as well as firms moving elsewhere, where they usually expand their carbon footprint. Nor does densification make sense as a climate antidote, given the rising temperatures associated with “urban heat islands.”

The tech boom has been used to justify Sacramento’s crushing regulatory and tax regime. It has also made it possible for apologists to ignore some 10,000 businesses that have left or expanded outside the state, many of them employing middle and working class people.

Ultimately California’s growing class bifurcation will demand solutions. Hedge fund billionaire-turned green patriarch Tom Steyer now insists that, to reverse our worsening inequality, we should double down on environmental and land use regulation but make up for it by boosting subsidies for the struggling poor and middle class. Certainly the welfare state in California — home to over 30 percent of United States’ on public assistance as of 2012 — will have to expand if the state stays on its present course.

In the coming years the state’s business leaders fear an ever more leftist, and fiscally damaging, regime after the departure of the somewhat frugal Brown. There are increased calls in Sacramento for new subsidized housing, a single payer healthcare system as well as a big boost to the minimum wage already enacted.

Ultimately California will pay — demographically, economically and socially — from its current surfeit of good intentions. Those who already own houses will not suffer immediately, but the new generation, immigrants and minorities will face an increasingly impossible burden. With its unparalleled natural assets, and economic legacy, California may be able to survive this toxic policy mix better than most places, but even in the Golden State reality has a way of showing its ugly face.

This piece originally appeared on Forbes.

Joel Kotkin is executive editor of NewGeography.com. He is the Roger Hobbs Distinguished Fellow in Urban Studies at Chapman University and executive director of the Houston-based Center for Opportunity Urbanism. His newest book is The Human City: Urbanism for the rest of us. He is also author of The New Class Conflict, The City: A Global History, and The Next Hundred Million: America in 2050. He lives in Orange County, CA.

Photo by Neon Tommy, via Flickr, using CC License.