Jerry Brown is supposed to be a different kind of politician: well informed, smart, slick, and skilled. While he has had some missteps, he’s always bounced back. His savvy smarts have allowed him to have a fantastically successful career while generally avoiding the egregious dishonesty that characterizes so many political practitioners.

So, I was shocked to read that he said that California’s poverty is a result of the State’s booming economy. Here’s part of the Sacramento Bee report:

Gov. Jerry Brown, whose pronouncements of California’s economic recovery have been criticized by Republicans who point out the state’s high poverty rate, said in a radio interview Wednesday that poverty and the large number of people looking for work are "really the flip side of California’s incredible attractiveness and prosperity."

The Democratic governor’s remarks aired the same day the U.S. Census Bureau reported that 23.8 percent of Californians live in poverty under an alternative calculation that includes the cost of living. Asked on National Public Radio’s "All Things Considered" about two negative indicators — the state’s nation-high poverty rate and the large number of Californians who are unemployed or marginally employed and looking for work — Brown said, "Well, that’s true, because California is a magnet.

"People come here from all over in the world, close by from Mexico and Central America and farther out from Asia and the Middle East. So, California beckons, and people come. And then, of course, a lot of people who arrive are not that skilled, and they take lower paying jobs. And that reflects itself in the economic distribution."

This is so incredibly wrong that I’m worried that Brown has lost his head and ability to reason. If he really believes what he said, he’s living in the past and he’s so ill informed as to be delusional. If he doesn’t believe what he said, I’m worried that his political skills have slipped. To my knowledge, he’s never said anything so clearly at odds with the truth in his career.

Here are the facts:

- California’s poverty is not where the jobs are, which is what we’d expect if what Brown said was true. Most of California’s jobs are being created in the Bay Area, a region of fabulous wealth. By contrast, California’s poverty is mostly inland. San Bernardino, for example, has the second highest poverty rate for American cities over 200,000 population, and no, it’s not because it’s a magnet. Most of California’s Great Central Valley is a jobs desert, but the region is characterized by persistent grinding poverty and unemployment. No one in recent years is moving to Kings County to look for a job.

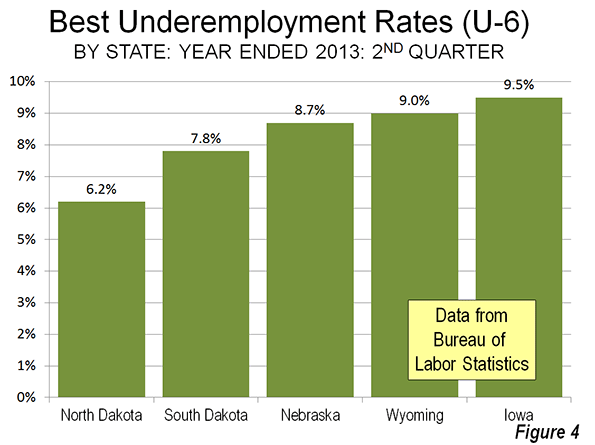

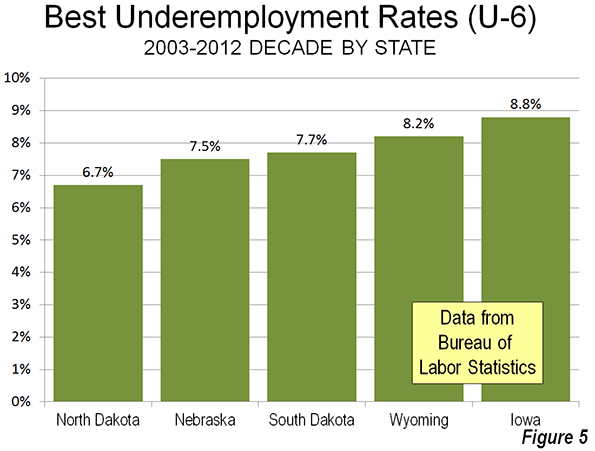

- States with opportunity have low poverty rates. North Dakota may have America’s most booming economy. According to the Census Bureau, North Dakota’s Supplemental Poverty Measure is 9.2 percent. That is, after adjustments for cost of living, 9.2 percent of North Dakotans live in poverty. The rate in Texas – a state with a very diverse population, and higher percentages of Latinos and African-Americans – is 16.4 percent. California leads the nation with 23.8 percent of Californians living in poverty.

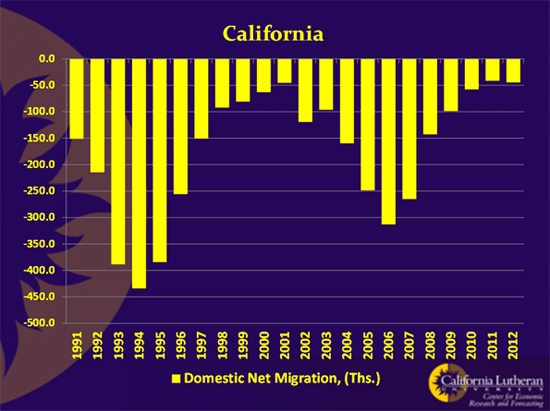

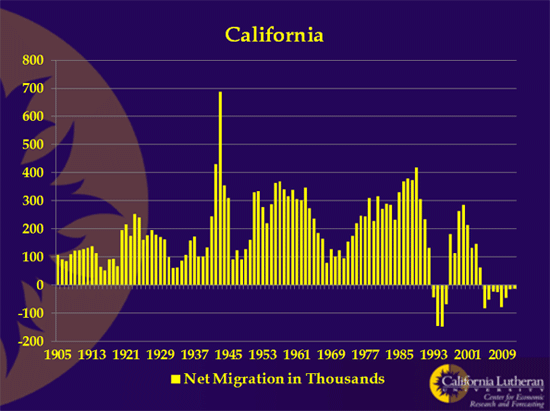

- According to the U.S. Census, domestic migration (migration between California and other states) has been negative for 20 consecutive years. That is, for 20 years more people have left California for other states than have come to California from other states. Wake up, Jerry, this is no longer your Dad’s state – or that of his successor, Ronald Reagan. This is a big change from when Brown was elected governor the first time. At that time, California was a magnet. It had a vibrant economy, one with opportunity. California was a place where you could have a career, afford a home, raise a family. It was where the American Dream was realized.

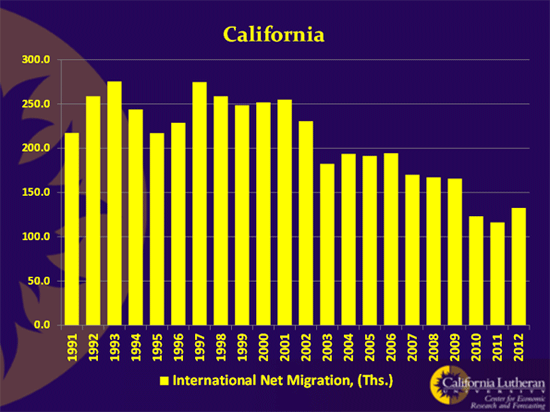

- How about the magnetic attraction for immigrants from all over the world? According to the Census Bureau, international migration to California is way down. The number of California international immigrants has been declining for a decade at least. Indeed, in recent years there have been about half as many international immigrants to California than we saw in the 1990s. Over the past decade, the number of foreign born increased more in Houston than the Bay Area and Los Angeles put together. Opportunity, not “attractiveness”, drives people to move.

- The result of negative domestic migration and falling international migration is the total migration to California has been negative in each of the past eight years. More people have left California than have come to California for eight consecutive years.

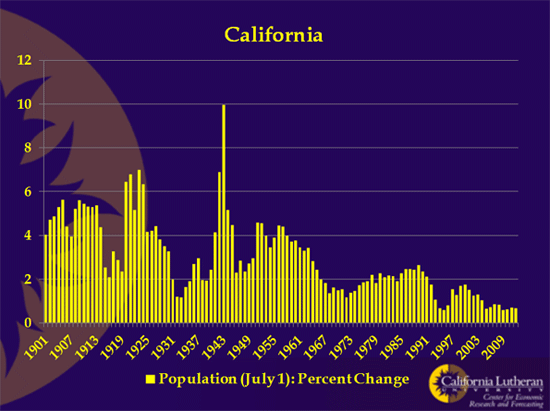

- California’s migration trends combined with falling birth rates has resulted in the lowest sustained population growth rates that California has seen.

The data are clear: Brown’s assertions have no basis in fact. California – with the exception only recently of the Bay Area – is not a magnet. California is not "incredibly attractive and prosperous." People are not coming from all over the world. California may beckon, but more are leaving, and those here are having fewer children. California’s seductive charms go only so far.

I don’t know if I’d prefer that Brown was delusional or lying. On the one hand, policy made from a delusional analysis of the world is sure to be bad policy. Brown, for example, may convince himself that Twitter, Google, and Facebook are the future of the California economy, without recognizing how few people, particularly from the working class or historically disadvantaged minorities, they employ. On the other hand, Brown is very skilled in the political arts. If someone as skilled as he has to resort to such outright misdirection, we may be in worse shape than I think.

Bill Watkins is a professor at California Lutheran University. and runs the Center for Economic Research and Forecasting, which can be found at clucerf.org.

Jerry Brown photo by Bigstock.