By the time I arrived in Silicon Valley in 1986 California’s middle class economy was already being remade by globalization. Globalization’s dramatic impact on northern California hit me square in the face the moment I arrived at my first career expo later that year at the Westin Hotel in Santa Clara. There I found myself surrounded by a multitude of H‑1B workers from all over the world, excitedly speaking in a myriad of languages. I was staggered. Born in the U.S.A., I felt like a foreigner in the land of my birth.

In this new Pacific Rim "promised land," an American-born engineer residing in Palo Alto would need four or five times his annual salary to purchase the same home his father had gotten with only two. Valley infrastructure was not keeping up with the expanding population and the inevitable supply-demand dynamic was rapidly dividing the middle class into winners and losers. The winners would enjoy at least a 4-bed/3-bath/2-car home and early retirement; the losers would compete for tiny 1-bed condos. This trend has not only continued but is escalating across a variety of benchmarks—both in the Valley and all over America.

Now, let’s get close to the ground and see if we can find who’s been dropping under the radar.

Some Are Hot, But Most Americans (Particularly White Males) Are Not

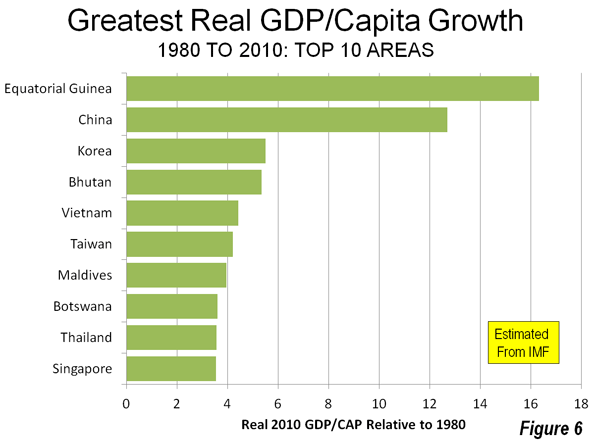

Half of Silicon Valley’s technology workforce is now Asian, and many come from abroad. This was already the case among software development engineers back in 1990 when I was working for Consilium. Hispanics, Latinos, and African-Americans are all losing ground, though not as quickly as whites.

US taxpayers have unknowingly funded a training program called JEEP to train foreign Asian students for jobs in some booming career fields such as offshore call centers that serve US businesses. As a result, according to Congressman Tim Bishop (D-New York), American workers have lost some five hundred thousand jobs in just five years.

Last November figures obtained from inside IBM seemed to indicate that for the first time more of the tech giant’s workforce would be employed in India than in the US. Of IBM’s total global workforce of 430,000 less than one quarter now work in the US. IBM benefits from the hefty difference in employee salaries, which can amount to as much as $100,000 per year.

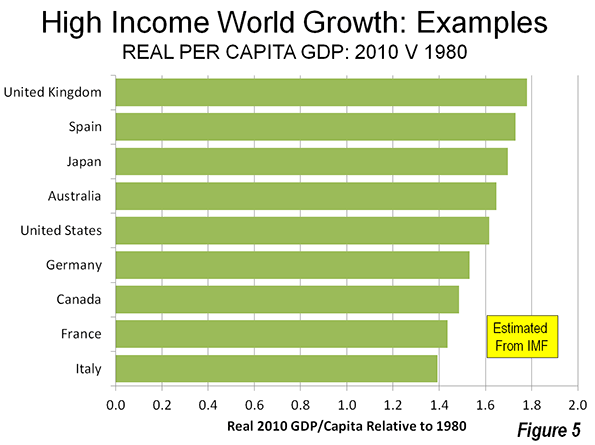

All this cost-cutting from H-1B work visas, outsourcing, and offshoring is having a leveling impact on US wages, including among technology specialists such as software development engineers and project managers—even though new technology developments continue at a breathtaking pace.

Age-Related Losers, Old and Young

When I arrived, you could see how youth-obsessed 80s Silicon Valley was. It still is, only more so. In her article Silicon Valley’s Dirty Secret: Age Bias, Sarah McBride details a number of cases of age-related bias that show how much tougher it is for the over-40 techie to find her next job than for the 20s person, even from another country. I know Age-bias first-hand. One day in 2002, while a technical writer for startup E2open, I was confronted by two young engineers: "What’s an over-40 dude doing here—aren’t you retired yet?"

It’s not just Silicon Valley anymore. A 2012 United States GAO report noted that "…long-term unemployment has particularly serious implications for older workers (age 55 and over). Job loss for older workers threatens not only their immediate financial security, but also their ability to support themselves during retirement."

Think you’re too young to worry about age? Think again. Even pretty young women might not be quite good enough in the brave new world. In 2011, clothing giant H&M reported that they are now using "perfect" virtual models—not real humans—for their online shopping site.

Globalization’s Broadband Impact on America

In The Slow Disappearance of the American Working Man, Bloomberg Businessweek Magazine (Aug. 2011) highlights the particularly devastating impact on the American male worker.

- "The portion of men who work and their median wages have been eroding since the early 1970s."

- "The portion of men holding a job—any job, full or part-time—fell to 63.5 percent in July 2012."

- "These are the lowest numbers in statistics going back to 1948."

- "Among the critical category of prime working-age men between 25 and 54, only 81.2 percent held jobs."

- "To put those numbers in perspective, consider that in 1969, 95 percent of men in their prime working years had a job."

- "After accounting for inflation, median wages for men between 30 and 50 dropped 27 percent"…putting them "back at their earnings capacity of the 1950s."

In Race Against the Machine (2011) MIT’s Erik Brynjolfsson and Andrew McAfee show how jobs formerly enjoyed by the median US worker are now being lost to cutting-edge technologies. Artificial Intelligence (AI) is to today’s white collar STEM worker what robotics was to many blue collar workers. We were already advancing this trend at Oracle in 1990 with the development of our SQL*Forms application generator, obviating the need for thousands of application developers.

A number of disturbing statistics indicate that US workers are now both producing and earning less.

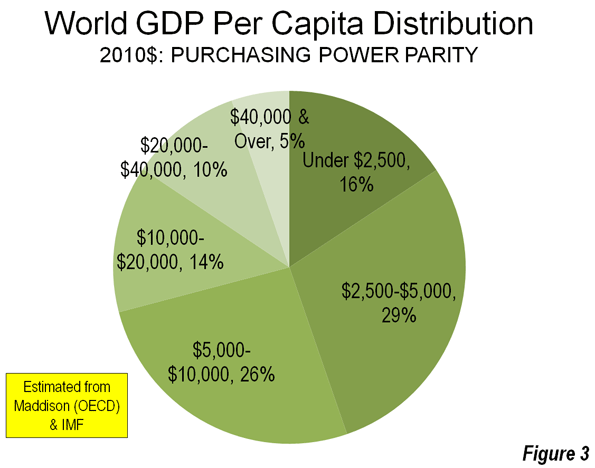

The Central Intelligence Agency World Factbook ranks the United States 11th in the world in GDP per capita. We used to be number 1. This figure indicates that while rich Americans keep getting ever richer, the middle class is producing less and less per capita. The US-born middle class worker keeps on sinking.

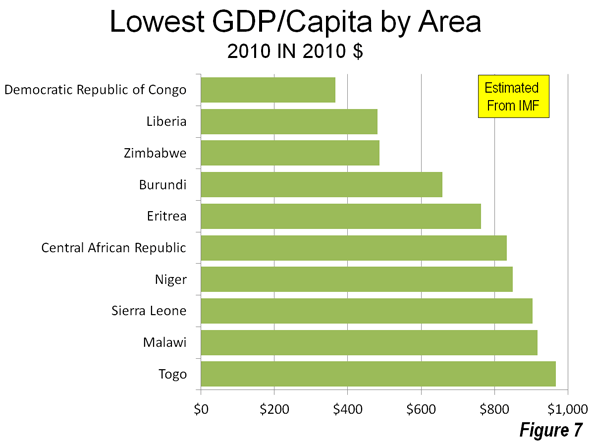

A recent National Employment Law Project report indicates that the current "recovery" continues to be slanted toward low-paying jobs, reinforcing the mounting inequality s. The fastest growing low-wage jobs include retail salespeople, food prep workers, waiters and waitresses, laborers and freight workers, office clerks and customer representatives, and personal and home care aides—mostly paying median hourly wages between $7.69 and $13.83 per hour. Is this America’s new path to "prosperity?"

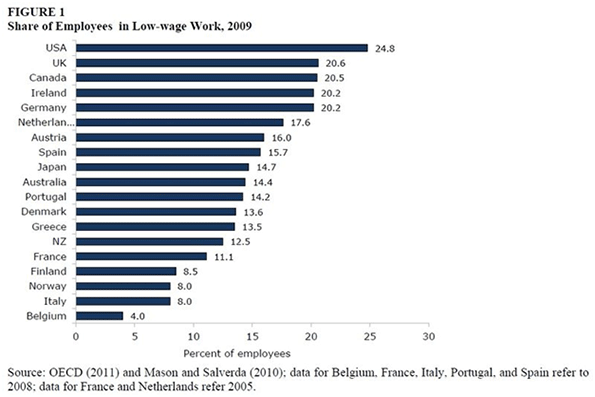

The Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) reports, amazingly, that the United States actually has a higher percentage of workers doing low-wage work than any other major industrialized nation:

The Future: Dimmest for the Brightest, Brightest for the Dimmest?

Last year a NY Times article covered the appalling plight of recent college grads. Half of today’s graduates are jobless or underemployed. They are more likely to be employed in jobs not requiring a college diploma—such as receptionists, cashiers and food-service helpers—than as engineers, physicists, or computer professionals.

And while Americans are busy paying for US corporations to move work to Asia, US federal employment accounts for the entire net increase in jobs since at least 2008. Washington’s cure to de-industrialization of the US has been to expand government payrolls. But is the creation of more and more "security" jobs and unnecessary bureaucracy the proper cure for persistent unemployment and swelling welfare rolls?

Where Do We Go From Here?

All of the benchmarks point to the unavoidable conclusion that ever more Americans are simply dropping under the economic radar screen. This includes some very broad downtrends for American workers of all races; "older" workers; young workers who perform work that robotics and AI are learning to do more cost-effectively; the American male workforce and middle income workers in general; and even recent college graduates. With neither the free market or government helping very much the message seems quite clear: globalization’s losers must get organized and work together for improved economic opportunity.

Rob Argento is a senior technical writer and project leader with a background in aerospace engineering and some 18 years in Silicon Valley with Oracle, Xerox, Microsoft, and Sony. His broad industry experience includes NASA, e-commerce, US Navy, Biotech, and PC Games. He has degrees in physics and theological studies.

Global population photo by Bigstock.