In the wilds of Louisiana’s St. James Parish, amid the alligators and sugar plantations, Lester Hart is building the $750 million steel plant of his dreams. Over the past decade, Hart has constructed plants for steel producer Nucor everywhere from Trinidad to North Carolina. Today, he says, Nucor sees its big opportunities here, along the banks of the Mississippi River, roughly an hour west of New Orleans by car.

“The political climate here is conducive to growth,” Hart explains as he steers his truck up to the edge of a steep levee. “We are here because so much is going on in this state and this region. With the growth of the petrochemical and industrial sectors, this is the place to be.” Already, some 500 people are working on the project. When completed in 2013, the plant—which is expected to process more than 3.75 million tons of iron ore a year—will create about 150 permanent jobs immediately. Another 150 are expected after a second development phase.

Nucor isn’t alone in coming to Louisiana, or to the vast, emerging region along the Gulf Coast. The American economy, long dominated by the East and West Coasts, is undergoing a dramatic geographic shift toward this area. The country’s next great megacity, Houston, is here; so is a resurgent New Orleans, as well as other growing port cities that serve as gateways to Latin America and beyond. While the other two coasts struggle with economic stagnation and dysfunctional politics, the Third Coast—the urbanized, broadly coastal region spanning the Gulf from Brownsville, Texas, to greater Tampa—is emerging as a center of industry, innovation, and economic growth.

The Gulf area long lacked industry. Even when the Spaniards and the French ruled it, the Gulf was a planters’ region, and its economy was largely dependent on exports of indigo, sugar, and cotton. The economy also relied on the slave labor that made such exports possible, a state of affairs that continued until the Civil War. After the war, the region therefore lost much of its economic influence as growth shifted to the rail-dominated east-west axis, though the construction of the Panama Canal eventually helped New Orleans and Mobile, Alabama, again become busy ports. Developing slowly, the Third Coast’s agricultural economy was dominated largely by tenant farmers, who in 1930 constituted more than 60 percent of the agricultural producers in an arc from Texas to Georgia.

The Gulf region also suffered from vulnerability to natural disasters. In 1900, more than a century before Katrina, the deadliest hurricane in American history all but destroyed Galveston, Texas. In 1927, the Great Mississippi Flood inundated a 27,000-square-mile area, much of it in Texas, Mississippi, and Louisiana. And then there was the hot and humid climate, especially miserable in those pre-air-conditioning days.

What Joel Garreau, in his landmark book The Nine Nations of North America, writes about the South as a whole—that it became a “region identified with stagnation—backward, rural, poor and racist, a colony of the industrialized north, enamored of an allegedly glorious past of dubious authenticity”—applied with particular force to the Gulf Coast, whose major cities, especially New Orleans, were seen as hopelessly corrupt and decadent. It’s no surprise that for much of the last century, the region exported people, particularly those with skills, to other parts of the United States.

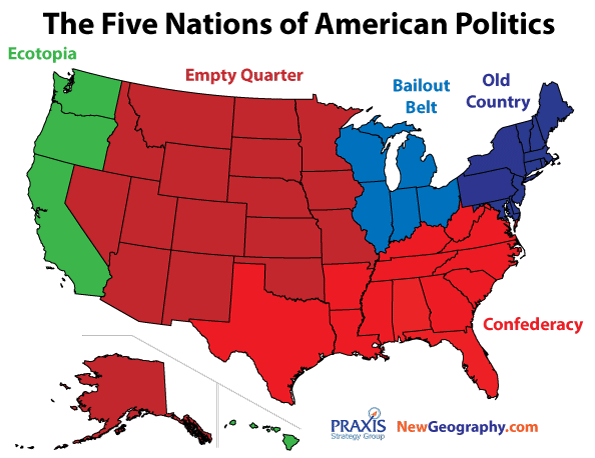

So it’s particularly striking that the region’s steady economic growth is now attracting so many people. Over the past decade, Texas and Florida have ranked first and second among the states in net domestic immigration, combining for a gain of roughly 2 million people. Together, Houston and Tampa have gained more than 1.5 million people over the course of the decade; in fact, in 2008 and 2009, net domestic migration to Houston was the highest of any major metropolitan area. An examination of migration flows to Houston, New Orleans, and Tampa by Praxis Strategy Group, where I work as a senior consultant, shows that many of their new citizens are coming from the East and West Coasts, especially New York and California. Also over the past decade, Houston has attracted as many foreign immigrants, relative to its population, as New York has—a considerably higher rate than in such historical immigration hubs as Chicago, Seattle, and Boston, though still lower than in San Francisco, Los Angeles, and Miami.

What’s more, the Third Coast is winning the battle of the brains. Over the past decade, according to the Census Bureau, 300,000 people with bachelor’s degrees have relocated to Houston. Between 2007 and 2009, as demographer Wendell Cox has chronicled, New Orleans—which had hemorrhaged educated people for the previous few decades—enjoyed the largest-percentage gain of educated people of any metropolitan area with a population of over 1 million. The New York Times reported in 2010 that Tulane University, the city’s premier higher-education establishment, had received nearly 44,000 applications, more than any other private school in the country. The largest group of applicants came not from Louisiana but from California, with New York and Texas not far behind.

Thanks to all this immigration, the population of the Third Coast has grown 14 percent over the past decade, more than twice the national average. The growth continued even when the Great Recession struck in 2008. Between 2008 and 2011, Houston grew by 6.7 percent, according to census estimates, while New Orleans expanded by 6.9 percent; over the same period, the nation’s population increased by only 2.5 percent. New Orleans, the biggest population loser in the first half of the last decade, is now the fastest-growing U.S. metropolitan region. Many smaller cities in the region—Brownsville, Gulfport, Lafayette, and Baton Rouge, for example—have also grown faster than the national average. Overall, the Gulf region is expected to be home to 61.4 million people by 2025, according to the Census Bureau.

Many of the region’s new arrivals are attracted by the low cost of living. The median home-price-to-income ratio in Houston, Tampa, and New Orleans is roughly one-half that of New York, Los Angeles, San Francisco, or San Jose. Over the last decade, Houston boasted the highest growth in personal income of any of the country’s 75 largest metropolitan areas.

The region’s most dramatic appeal, however, is its remarkable employment growth. Between 2001 and 2012, the number of jobs along the Third Coast, according to Economic Modeling Specialists International (EMSI), increased by 7.6 percent, well over three times the national growth rate. The vitality of the Third Coast persisted even during a brutal recession, with four metropolitan areas—Houston, Corpus Christi, Brownsville, and New Orleans—gaining jobs between 2008 and 2012, even as the nation’s job rolls shrank by 3.6 percent. Of the three states that have recovered all the jobs lost during the recession, two—Texas and Louisiana—are on the Third Coast.

The region’s job-creation engine is powered by the growth of basic industries: manufacturing, energy, and agricultural commodities. The region from south Texas to Florida now bristles with scores of new steel plants, petrochemical facilities, and factories producing everything from airplanes to canned food. Along with the Great Plains and the Intermountain West, the Gulf Coast has enjoyed a huge boost from energy and other commodity growth. Over the past decade, Texas alone has added nearly 200,000 oil- and gas-sector jobs, with an average salary of about $75,000. Thanks largely to expansion in energy, manufacturing, and engineering services, Houston now boasts a considerably higher per-capita concentration of STEM jobs—those relating to science, technology, engineering, or mathematics—than Chicago, Los Angeles, or New York, according to an analysis by EMSI.

The magazine Site Selection says that four of the Gulf states are among the nation’s 12 most attractive states to investors: Texas topped the list, with Louisiana ranking seventh, Florida tenth, and Alabama 12th. Texas and Louisiana also ranked first and third among the 50 states in terms of new plants built or being constructed. “There’s been a drastic change in the business climate here,” says Chris McCarty, director of the University of Florida’s Bureau of Economic and Business Research. “A lot of regulations have been moved aside, and there’s a big push by the state to get out of the way.”

Energy is the key driver. The Third Coast already accounts for roughly 28 percent of the nation’s oil and gas employment, despite the federal crackdown on offshore drilling after the 2010 Deepwater Horizon disaster. The region boasts new shale plays, such as those now being developed in northern Louisiana, and massive crude reserves, which follow the arc of the Gulf Coast from Brownsville to New Orleans.

The future for American energy is bright. According to the consultancy PFC Energy, the United States is on course to surpass Russia and Saudi Arabia as the world’s leading oil and gas producer sometime during this decade. With the Atlantic and Pacific coasts either banning or sharply curtailing energy production, the Gulf’s pro-business, right-to-work states have emerged as the likely staging ground for this energy resurgence. Here, unlike in California or New York, support for energy development tends to be highly bipartisan. Third Coast Democrats—such as Louisiana U.S. senator Mary Landrieu, New Orleans mayor Mitch Landrieu (her brother), and Houston mayor Annise Parker—can be as ferocious in their defense of the industry as any Republican. “Texas and Louisiana understand the oil business,” says Ralph Phillip, vice president of a Valero oil refinery located just a few miles from the rising Nucor steel plant. “They understand what this industry is all about and expect you to manage the risks. If you want to do a permit in California, they won’t return your call. But here they want everything to work.”

Not only does the energy industry employ people and pay them well; the effect works in reverse, too, with a growing pool of skilled workers offering companies like Nucor and Valero a compelling reason to expand into the Third Coast. “When you are building a petrochemical facility, you have a great need for skills in such things as maintenance and construction,” Phillip points out. “If you open up in another part of the country, you have to bring in people to run things. Here, the skills are all over the Gulf.”

Another important part of the region’s economy is exports, since trade patterns are shifting away from the Atlantic and Pacific coasts and toward the Gulf. Since 2003, the Third Coast’s total exports have tripled in value, and its share of total American exports has grown from roughly 10 percent to nearly 16 percent. Last year, trade reached record levels at the Port of New Orleans, says Donald van de Werken, director of the U.S. Export Assistance Center in that city. Louisiana has become a dominant player in the agricultural-export industry, with half of the nation’s grain exports going through the state’s ports. Houston now ranks as the top port in the United States in terms of total value of exports; New Orleans ranks fifth.

The trends favoring the Third Coast will accelerate further once the $5.25 billion Panama Canal expansion is completed in 2014, as I pointed out in Forbes last year. The wider canal will be able to accommodate Asian megaships, which are currently forced to dock in California. That will open the Gulf to more Pacific trade, since most northeastern and West Coast ports have been reluctant to make the necessary capital investments to capture it. China’s abandonment of the Maoist ideal of self-sufficiency and its growing willingness to rely on imports of food and other items represent a huge opportunity for the region.

When Garreau published Nine Nations 30-some years ago, he predicted that as growth kicked in, the Gulf region would “clot” into an archipelago of cities similar to the Boston–New York–Washington megalopolis, or to the band stretching from San Diego through Los Angeles and San Francisco to Portland and Seattle. If he proves right, Houston will be the hub of this new system, much as New York anchors the East Coast and Los Angeles the West.

The greater Houston metropolitan area is one of the fastest-growing in the country; its population, now 6 million, is expected to double over the next 20 years. Houston is also the nation’s third-largest manufacturing city, behind New York and Chicago. Over the past decade, the city and its surrounding communities have added almost 20,000 heavy-manufacturing jobs, the most of any metropolitan area in the United States. Further, Houston has the third-largest representation of consular offices, after Los Angeles and New York, and it hosts more Fortune 500 companies—22, as of 2011—than any city other than Gotham. Over the past half-century, says Federal Reserve economist Bill Gilmer, Houston has consolidated its position as the center of the global fossil-fuel industry. In 1960, Houston was home to just one of the nation’s large energy firms, ranking well behind New York, Los Angeles, and even Tulsa; by 2007, 16 such companies were headquartered in Houston, more than in those three cities combined.

The burgeoning health-care industry is also finding a home in Houston, especially at the Texas Medical Center—“the largest medical complex in the world,” its website boasts. Like so many things in Houston, this cluster of 48 nonprofit hospitals, colleges, and universities owes its existence largely to the energy industry. According to its chief executive, Richard Wainerdi, the center benefits from “probably the biggest confluence of philanthropy in the world, and a lot of it is oil money.” Every day, 160,000 people enter the vast campus, equal in size to Chicago’s downtown Loop; its office space, now over 28.3 million square feet, exceeds not only that of downtown Houston but also that of downtown Los Angeles. The figure is expected to surpass 41 million square feet by the end of 2014, making the center the seventh-largest business district in the nation.

Houston’s solid business climate empowers entrepreneurs. Between 2008 and 2011, according to a study by EMSI, the number of self-employed workers grew more quickly in Houston than in any other large metropolitan area. Greater numbers of educated workers are coming, too: Houston’s total increase in people with bachelor’s degrees over the past decade bested Philadelphia’s, was three times that of San Jose, and was twice that of San Diego. “I don’t get the pushback I used to get” from potential recruits, says Chris Schoettelkotte, who founded Manhattan Resources, a Houston-based executive-recruiting firm, 13 years ago. “You try to find a city with a better economy and better job prospects than us!”

Though Houston has always been a good place to do business, it continues to suffer from a bad cultural image. In 1946, journalist John Gunther described Houston as a place “where few people think about anything but money.” It was, he added, “the noisiest city” in the nation, “with a residential section mostly ugly and barren, a city without a single good restaurant and of hotels with cockroaches.” The miserable city that Gunther described no longer exists, but residents on the other two coasts have been slow to acknowledge that development, despite Houston’s first-class museums and lively restaurant scene. “Let’s face it, we have a bad reputation,” says L. E. Simmons, a legendary Houston energy investor. “But the good news is, it keeps the stylish opportunists out. It makes us kind of an urban secret.”

Houston’s cultural weakness—more perceived than real these days—has long been New Orleans’s strong suit. Yet the Big Easy’s long-standing appeal to artists, musicians, and writers did little to dispel the city’s image as merely a tourist haven, and a poor one at that. The problem, as Hurricane Katrina made all too plain, was a corrupt city plagued by enormous class and racial divisions and one of the lowest average wages in the country. The city’s urban core continues to endure one of the highest violent-crime rates in the nation.

Though energy is responsible for much of New Orleans’s recent economic growth, the city has also begun attracting the information industry. Since 2005, New Orleans’s tech employment has surged by 19 percent, more than six times the national average. And at a time when movie production has dropped nationally, Louisiana has nearly tripled its production of motion pictures, from 33 per year in 2002–07 to 92 per year in 2008–10.

East of New Orleans, Mobile has a different strength: manufacturing. Nearly 1.5 million cars and trucks are made within four hours of the city. In fact, the Third Coast, together with the adjacent southeastern manufacturing belt, is now competing with the Great Lakes as the center of the automotive industry. And Tampa, with robust population growth and Florida’s largest port—including a container terminal expanding from 40 acres to 160 acres—is poised perfectly to take advantage of any opening of Cuba, a country with which the city has had a long economic relationship.

The region’s ascendancy, however, faces significant impediments. Gilmer says that the greatest risk to growth comes from Washington, especially if a second-term Obama administration cracks down even more aggressively on offshore oil development. Federal regulators’ reluctance to let drilling resume in the wake of the BP oil spill ruined hundreds of New Orleans–area businesses. Potentially strict new controls on extracting gas by means of hydraulic fracturing could slow the energy boom further, which in turn would derail the expansion of petrochemical and other manufacturing facilities.

Perhaps more troubling are social problems, some the legacy of centuries of underdevelopment. Despite the influx of skilled and college-educated workers, Third Coast states continue to lag in college graduation rates and the percentage of their adult populations with college degrees. Of the 18 metropolitan areas across the Third Coast, only two—Tallahassee and Houston—have a higher percentage of college grads than the national average of 30 percent. When you rank states by their students’ proficiency in math and science, only one Third Coast state—Texas—sits near the middle of the list. Efforts to reform public education—notably, Louisiana’s new statewide voucher program and aggressive expansion of charter schools—offer some hope of addressing these weaknesses. In a new report, government efficiency expert David Osborne describes New Orleans’s reforms as a “breakthrough.” The results, he says, are “spectacular: test scores, graduation rates, college-going rates, and public approval have more than doubled in five years.” He adds, “I believe this is the single most important experiment in American education today.”

And the obstacles facing the Third Coast today aren’t so different from those that once confronted other American economic dynamos. In the nineteenth century, New York was seen as a hopelessly corrupt sewer. In the early twentieth century, Los Angeles was dismissed as superficial and equally corrupt, with only one industry: fantasy. Few would make those claims today.

It is much the same with the Third Coast. Weather, education, and, in some places, a legacy of corruption still present considerable challenges to its ascendancy. But if the region can surmount these challenges—and it appears to be succeeding at this—the Third Coast could become one of the major forces in twenty-first-century America.

Joel Kotkin is executive editor of NewGeography.com and is a distinguished presidential fellow in urban futures at Chapman University, and contributing editor to the City Journal in New York. He is author of The City: A Global History. His newest book is The Next Hundred Million: America in 2050, released in February, 2010.

This piece originally appeared at The City Journal.

New Orleans photo by Bigstock.

Joel Kotkin is a City Journal contributing editor and the Distinguished Presidential Fellow in Urban Futures at Chapman University.