The October 29, 2009 issue of Time Magazine had an article titled “Why California is America’s Future.” I sure hope not. California is fast becoming a post-industrial hell for almost everyone except the gentry class, their best servants, and the public sector.

We only need a few numbers to demonstrate that California is clearly on the wrong track:

- California’s unemployment rate is over 12 percent, about a third higher than the United States.

- Only eight of California’s 58 counties have unemployment rates in single digits.

- California has lost jobs in four of the past six months for which we have data, while the United States has gained or had no change in jobs in each month over that period.

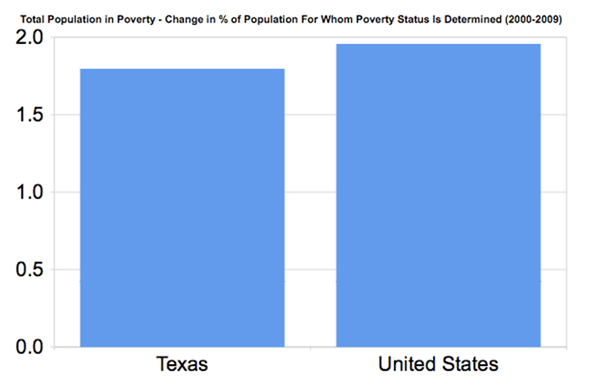

- California’s poverty rate is 16.1 percent compared to the United States 15.1 percent. The rate goes way up when adjusted for the cost of living. For example, the respected Public Policy Institute of California estimated that Los Angeles County’s 2007 poverty rate increased 11 percentage points from 15 to 26 percent, when adjusted for cost of living.

- Two California cities, Fresno and San Bernardino, are among the ten poorest American cities with populations over 200,000. In fact, San Bernardino’s 34.6 poverty rate is the second highest of these cities, exceeded only by Detroit.

- Unemployment among college educated is 34 percent higher in California than in the United States, while Los Angeles’s college educated unemployment rate is almost a whopping 80 percent above the United States’ rate.

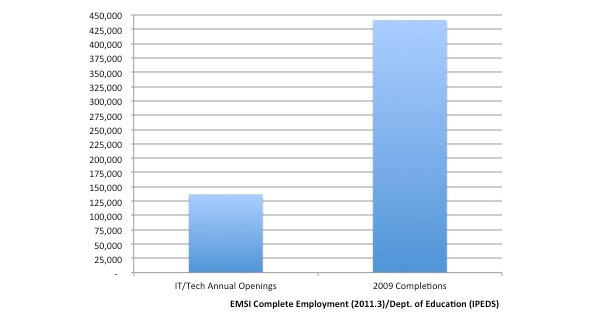

- According the California Department of Education, California’s public colleges and universities graduate over 150,000 students a year, while California’s Economic Development Department is forecasting less than 50,000 openings a year for jobs that require a college degree.

Of course, that’s not the future that Time was selling. Time’s future was a “dream state,” a magical place where enlightened pioneers, guided by their superior vision and funded by venture capital, would lead the world in innovation and environmental bliss. California firms, like Solyndra, would lead the competition to a competitive new green economy. No kidding, they named Solyndra:

"It’s (California) building massive power plants for utilities, as well as roof panels for big-box stores, complete subdivisions and individual homes. Prices are plummeting, and competition is fierce, most of it from California firms like BrightSource, Solar City, eSolar, Nanosolar and Solyndra."

Along the way to this brave new world, there would be a new, “green” gold rush “beckoning dreamers who want to cook Korean tacos or convert fuel tanks into hot tubs.”

That vision turned out to be about as real as Disneyland – but not as profitable.

Time wasn’t alone. Brett Arends had a similar piece, The Truth about California, in November 2010, and the ever-optimistic duo of Bill Lockyer and Stephen Levy had a December 2010 piece, California isn’t Broken.

Visitors can be forgiven for seeing California as a bit of paradise on earth. It is. I am a native myself who could not wait to return from my job at the Federal Reserve in Washington, DC. I remember going to Santa Barbara in October for my UCSB job interview. Santa Barbara was magical to me, after enduring weeks of dreary and increasingly cold East Coast weather. Santa Barbara was warm and sunny, and people were wearing the minimum legal requirements, and State Street was alive and vibrant with a happy energy I hadn’t seen since I’d left California for my East Coast job over a year before.

I wanted that job.

You can still have that experience in certain spots in California. There’s no doubt, California has abundant charms. It can seduce almost anyone.

But there is a lot of California that visitors don’t see. They don’t see the many communities in California’s central valley where unemployment rates of over 15 percent are typical, where people live in substandard housing and face the prospect of a lifetime in an ignored underclass.

Well, they are not exactly ignored. They receive food stamps and other subsidies, but they are denied opportunity, social mobility, or the confidence and pride that come with self-sufficiency.

You don’t have to leave Santa Monica or Santa Barbara to see poverty without opportunity though. Just blocks from Santa Barbara’s State Street or Santa Monica’s Third Street Promenade, over-crowded units , packed sometimes by several families, are the norm, because Coastal California’s housing prices are not related to the local economy. Statewide, 28 percent of California’s children live in crowded housing. This is the highest rate in the nation, tied only with Hawaii.

When you live here, you can’t avoid the signs of California’s decline. Beaches I walked with High School dates are no longer safe at night. Water lines in Los Angeles burst with alarming frequency. Our roads are approaching gridlock and are littered with potholes. Electrical cutbacks are common in hot weather. Water is increasingly scarce, except in very rainy years. Our primary schools are clearly in decline. Even California’s higher education system, once the envy of the world, has passed its prime. Places like the University of Texas or University of North Carolina are now real competitors.

It wasn’t always this way, and it doesn’t have to be in the future. When I started my career, California was a place of opportunity. One could have a career, own a home, and raise a family.

Not any more – not unless you have a trust fund or a secure pensioned public employee job.

That’s why California’s middle class is leaving, looking for opportunity and affordable housing. The evidence is in the migration data. Domestic migration has been negative for over a decade. Perhaps even more telling, only 23 percent of U.S. illegal immigrants are coming to California today, down from about 42 percent in 1990. Even the lowest skilled newcomers know there’s shrinking opportunity here.

California has a problem, and it’s high time the political class accepted the fact.

Two steps need to be taken before any problem can be solved. You need to recognize you have a problem. Then you need to identify the problem. Unfortunately, it appears that among Sacramento’s leadership, only Gavin Newsom even recognizes that California has a problem. Governor Brown gives lip service to jobs, but like Schwarzenegger before him, identifies the failed command and control policies of the green movement as the source of the new jobs. Solyndra has become the poster child for this fantastical policy failure.

California’s economic future is pretty grim, until Sacramento takes off the blinders and admits it has a problem. Until then, things are likely to get much worse before they get better.

Bill Watkins is a professor at California Lutheran University and runs the Center for Economic Research and Forecasting, which can be found at clucerf.org

Photo illustration by krazydad/jbum.