Smaller, more nimble urban regions promise a better life than the congested megalopolis.

Most of the world’s population now lives in cities. To many academics, planners and developers, that means that the future will be dominated by what urban theorist Saskia Sassen calls “new geographies of centrality.” According to this view, dense, urban centers with populations in excess of 20 million—such as metropolitan Tokyo, New Delhi, Sao Paolo and New York—are best suited to control the commanding heights of global economics and culture in the coming epoch.

In fact, the era of bigger-is-better is passing as smaller, more nimble urban regions are emerging. These efficient cities, as I call them, provide the amenities of megacities—airports, mass communication, reservoirs of talent—without their grinding congestion, severe social conflicts and other diseconomies of scale.

Megacities such as New Delhi, Mumbai, Sao Paolo and Mexico City have become almost unspeakably congested leviathans. They may be seen as “colorful” by those engaging what writer Kennedy Odede calls “Slumdog tourism.” They may also be exciting for those working within the confines of “glamour zones” with high-rise office towers, elegant malls, art galleries and fancy restaurants. But most denizens eke out a meager existence, attractive only compared to even more dismal prospects in the countryside.

Consider Mumbai, with a population just under 20 million. Over the past 40 years, the proportion of its citizens living in slums has grown from one in six to more than half. Mumbai’s brutal traffic stems from a population density of more than 64,000 per square mile, fourth-highest of any city in the world, according to the website Demographia.

Many businesses and skilled workers already are moving to smaller, less congested, often better run cities such as Bangalore, where density is less than half that of Mumbai. Much of this new growth takes place in campus-like settings on the edge of town that take advantage of newer roads, better sanitation systems and sometimes easier access to airports. Companies like Alcatel-Lucent and Infosys offer their employees facilities more similar to those of Silicon Valley or suburban Austin than to Mumbai or Kolkata (formerly Calcutta).

Consider also Singapore and Tel Aviv, which are among the best models for the efficient cities of the future. At its founding in 1965 after independence from Malaysia, Singapore’s per capita GDP was about that of Guatemala and well below that of Venezuela and Iraq. Today it equals, on a purchasing power basis, that of most Western cities including London, Sydney and Miami.

The city-state bears no resemblance to the typical unsanitary and disorderly tropical metropolis. Singapore’s roughly five million citizens live under efficient (if heavy handed) government. With its modern port, airport and excellent transport network, Singapore consistently ranks as the No. 1 locale for ease of doing business by the World Bank. Over 6,000 multinational corporations including Seagate, IBM and Microsoft have a large presence in Singapore.

Tel Aviv represents a decidedly different approach to building the efficient city. With roughly two million people in its metropolitan area, this little dynamo produces the vast majority of Israel’s soaring high-tech exports, is home to a preponderance of the country’s financial institutions and has established itself as the global center of the diamond industry. Incomes in the region are as much as 50% above Israel’s national average.

Tel Aviv’s pleasure-loving denizens may differ markedly from more controlled Singaporeans—or the usually more religious citizens of Jerusalem—but they employ many of the key efficient city advantages: a sharp focus on business, a well-developed sense of place and a first-class communications infrastructure. The city’s tech industry includes firms such as Microsoft, Cisco, Google and IBM. It is home to Israel’s only stock exchange and most of the country’s resident billionaires.

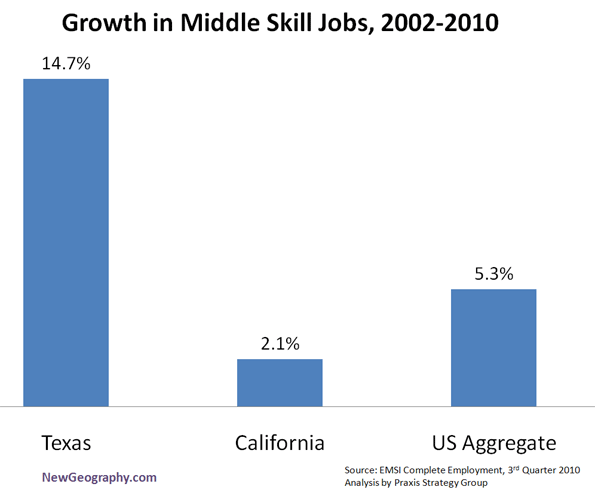

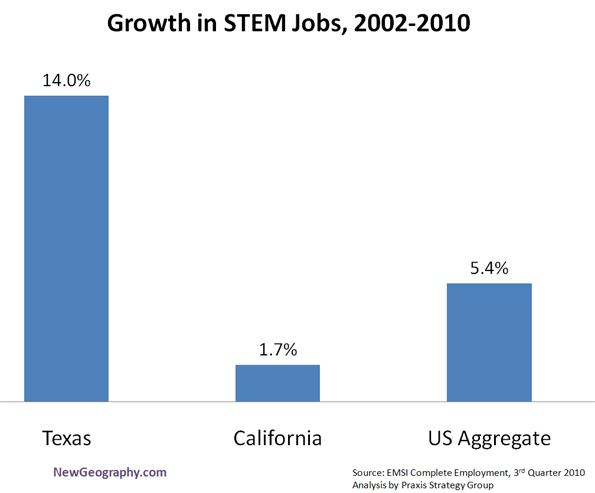

The U.S. is also embracing the efficient city. Between 2000 and 2008, notes demographer Wendell Cox, metropolitan areas of more than 10 million suffered a 10% rate of net outmigration. The big gainers were generally cities with 100,000 to 2.5 million residents. The winners included business-friendly Texas cities and other Southern locales like Raleigh-Durham, now the nation’s fastest-growing metro area with over one million people. You can add rising heartland cities like Columbus, Indianapolis, Des Moines, Omaha, Sioux Falls, Oklahoma City and Fargo.

Some of these—such as Austin, Columbus, Raleigh-Durham and Fargo—thrive in part by being college towns. Others like Houston, Charlotte and Dallas have evolved into major corporate centers with burgeoning immigrant populations. But they thrive because they are better places for most to live and do business.

Take the critical issue of getting to work. According to the American Community Survey, the average New Yorker’s daily trip to work takes 35 minutes; the average resident of the Kansas City or Indianapolis region gets to the office in less than 13 minutes. That adds up in time and energy saved, and frustration avoided.

The largest American cities—notably New York, Los Angeles and Chicago—also show the most rapid decline in middle-class jobs and neighborhoods, with a growing bifurcation between the affluent and poor. In these megacities, high property prices tend to drive out employers and middle-income residents. By contrast, efficient cities are where most middle- and working-class Americans, and their counterparts around the world, will find the best places to achieve their aspirations.

This article originally appeared at the Wall Street Journal.

Joel Kotkin is executive editor of NewGeography.com and is a distinguished presidential fellow in urban futures at Chapman University. He is author of The City: A Global History. His newest book is The Next Hundred Million: America in 2050

, released in February, 2010.

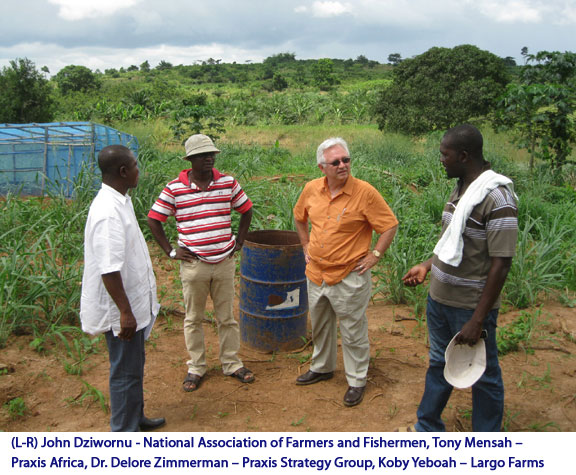

Today he is working on bringing about 200 acres into production on his farm. Over the past five years Koby has built roads, cleared land, accessed water and prepared for production. With a number of full-time villagers who are on the farm every day caring for crops and land, he visits the farm about three days a week, but his mind is on the farm every day. He is anxious for the day when he can bring all of his 850 acres into production and be able to spend seven days a week on the farm. Until then he continues his role as an education consultant recruiting students to schools in Ghana in order to support his family, while spending as much time as he can feeding his passion for farming.

Today he is working on bringing about 200 acres into production on his farm. Over the past five years Koby has built roads, cleared land, accessed water and prepared for production. With a number of full-time villagers who are on the farm every day caring for crops and land, he visits the farm about three days a week, but his mind is on the farm every day. He is anxious for the day when he can bring all of his 850 acres into production and be able to spend seven days a week on the farm. Until then he continues his role as an education consultant recruiting students to schools in Ghana in order to support his family, while spending as much time as he can feeding his passion for farming. Koby grows pineapple, maize, peppers, tomatoes and okra. In the near future he plans to add mushrooms, snail production, and has begun work developing a fish pond for Tilapia production. The diversification is impressive. He is also growing several different varieties of specialty potatoes in a custom greenhouse. His plans are to increase potato seed production for planting on his farm and to educate other farmers on growing these potatoes in hopes of expanding acreage around the region. He will seek and secure markets for the potatoes and work to build a reliable and effective means for the region to become a trusted supplier. It is upon the backs of individual farmers and small business operators that economic success will be built.

Koby grows pineapple, maize, peppers, tomatoes and okra. In the near future he plans to add mushrooms, snail production, and has begun work developing a fish pond for Tilapia production. The diversification is impressive. He is also growing several different varieties of specialty potatoes in a custom greenhouse. His plans are to increase potato seed production for planting on his farm and to educate other farmers on growing these potatoes in hopes of expanding acreage around the region. He will seek and secure markets for the potatoes and work to build a reliable and effective means for the region to become a trusted supplier. It is upon the backs of individual farmers and small business operators that economic success will be built.  Koby’s vision is to turn his farm into a key center of commerce for the village. When he puts out the call for harvest help 40 to 100 people arrive at his farm looking for work, forcing Koby to turn people away. But he has plans to grow and to create a solid source of continued employment for the villagers. His agriculture plan calls for planting dates staggered every six weeks, year round.

Koby’s vision is to turn his farm into a key center of commerce for the village. When he puts out the call for harvest help 40 to 100 people arrive at his farm looking for work, forcing Koby to turn people away. But he has plans to grow and to create a solid source of continued employment for the villagers. His agriculture plan calls for planting dates staggered every six weeks, year round.  The villages in rural Ghana are agrarian in nature, mainly for subsistence but also for commercial gain. There is available land, potentially productive but largely untouched in this region. There are also many able hands available in the nearby villages looking for productive work, but too often idled by lack of need for their assistance. Koby Yeboah sees an opportunity to make a difference for the region by setting a strong example for others and helping fellow farmers succeed. It is a sense of honor and commitment not readily found among your average 27 year old, but certainly not lost on this man.

The villages in rural Ghana are agrarian in nature, mainly for subsistence but also for commercial gain. There is available land, potentially productive but largely untouched in this region. There are also many able hands available in the nearby villages looking for productive work, but too often idled by lack of need for their assistance. Koby Yeboah sees an opportunity to make a difference for the region by setting a strong example for others and helping fellow farmers succeed. It is a sense of honor and commitment not readily found among your average 27 year old, but certainly not lost on this man. An example of his commitment to the region, Koby has created a “model farm” just outside the village of Gomoa Adumase. Here on one acre of land he has tilled and prepared the soil and is demonstrating advanced farming practices for raising pineapple. He is teaching other farmers and villagers in the region about the new farming practices so they can learn and produce on their own, and doing it in an entirely hands-on environment. (Photo)

An example of his commitment to the region, Koby has created a “model farm” just outside the village of Gomoa Adumase. Here on one acre of land he has tilled and prepared the soil and is demonstrating advanced farming practices for raising pineapple. He is teaching other farmers and villagers in the region about the new farming practices so they can learn and produce on their own, and doing it in an entirely hands-on environment. (Photo) The sense of community in the area is strong and Koby has grown to become an important part of it. Knowing that the villagers live on tight budgets he says, “I contribute all he can,” often purchasing school uniforms for a number of the children. But, the support doesn’t end there. Just outside the village lies the Gomoa Buduatta Orphanage, home to 16 beautiful young boys and girls who find a safe and secure place to live and go to school. Koby has taken on the incredibly honorable challenge of supporting the orphanage to the best of his ability. Again he says, “I contribute all I can” and you know that it is well appreciated.

The sense of community in the area is strong and Koby has grown to become an important part of it. Knowing that the villagers live on tight budgets he says, “I contribute all he can,” often purchasing school uniforms for a number of the children. But, the support doesn’t end there. Just outside the village lies the Gomoa Buduatta Orphanage, home to 16 beautiful young boys and girls who find a safe and secure place to live and go to school. Koby has taken on the incredibly honorable challenge of supporting the orphanage to the best of his ability. Again he says, “I contribute all I can” and you know that it is well appreciated.

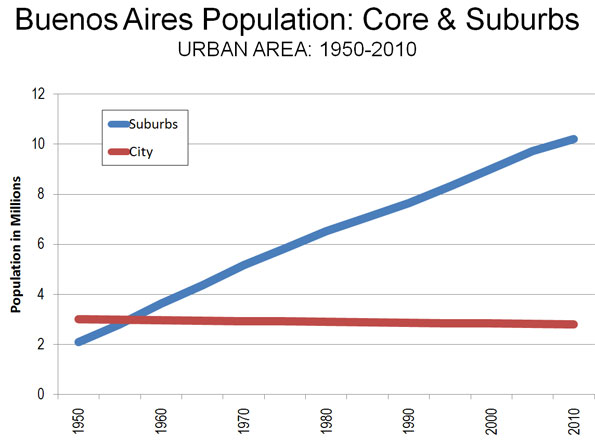

Population and Distribution: According to the last census (2001), the city of Buenos Aires had fewer people than in 1947,

Population and Distribution: According to the last census (2001), the city of Buenos Aires had fewer people than in 1947,

The suburban poverty is far more pervasive to the southwest and the southeast. Many neighborhoods look similar to modest suburbs in Mexico City, though without the pervasive informal settlements. More people live in informal settlements in the suburbs than in the city, with estimates putting the number at above 500,000.

The suburban poverty is far more pervasive to the southwest and the southeast. Many neighborhoods look similar to modest suburbs in Mexico City, though without the pervasive informal settlements. More people live in informal settlements in the suburbs than in the city, with estimates putting the number at above 500,000.