There are few more bankrupt arguments against suburbanization than the claim that it consumes too much agricultural land. The data is so compelling that even the United States Department of Agriculture says that “our Nation’s ability to produce food and fiber is not threatened” by urbanization. There is no doubt that agricultural production takes up less of the country’s land than it did before. But urban “sprawl” is not the primary cause. The real reason lies in the growing productivity of American farms.

Since 1950, an area the size of Texas plus Oklahoma (or an area almost as large as France plus Great Britain) has been taken out of agricultural production in the United States, not including any agricultural land taken by new urbanization (Note 1). That is enough land to house all of the world’s urban population at the urban density level of the United Kingdom.

America’s Spectacular Agricultural Productivity

Even with less land, agriculture’s performance has been stunning. According to US Department of Agriculture data, US farm output rose 160% between 1950 and 2008. Productivity per acre rose 260%. In particular , California’s farms – often cited as victims of sprawl – have done quite well. Between 1960 and 2004 (Note 2), the state’s agricultural productivity rose 2.3% annually and 3.0% per acre. By comparison national agricultural productivity rose less over the same period at 1.7% overall and 2.2% per acre.

According to the United States Department of Agriculture, from 1990 to 2004 (latest data), California’s agricultural production rose 32% and on less farm land.

Of course, there has been substantial reduction of farmland close to some metropolitan areas, but overall the impact of urbanization nationally has not been substantial. For example, since 1950:

- The farmland reduction in largely rural downstate Illinois has been four times that of the vast former rural areas of metropolitan Chicago, which is home to the world’s third most “sprawling” urban area, after New York and Tokyo (see photograph, above).

- The farmland reduction in the Phoenix metropolitan area has been 6 times the expansion of urbanization.

In addition, the nation’s agriculture is subsidized to the tune of more than $15 billion annually, which is strong evidence that more land is being farmed than is required. Subsidies increase the supply of virtually anything beyond its underlying demand. This can be illustrated by imagining how much less transit service there would be if it were not 80% subsidized. Suffice it to say, America is not threatened by “disappearing farmland.”

America has less farmland because it has not needed as much as before to serve its customers. Thus, considerable farmland has been returned to a more natural state. Generally, this has got to be good for the environment. Land that is left to nature does not require fertilization, for example. The same interests that have frequently claimed that farmland has been disappearing also decry the loss of open space. In fact, the withdrawal of redundant farmland has produced considerable open space – call it open space sprawl.

Repeat it Often Enough….

None of this has kept “disappearing farmland” from being a rallying cry among those who would construct Berlin Walls around the nation’s urban areas. Yet the extent to which Bonnie Erbe of Politics Daily and National Public Radio embraced the fiction was surprising. Her “Vanishing Farmland: How It’s Destabilizing America’s Food Supply,” was accompanied by “meant to indict” photograph of farm equipment next to new suburban housing.

Ms. Erbe’s principal source was a web page from the American Farmland Trust, which seeks to conserve farm land. In its California Agricultural Land Loss & Conservation: The Basic Facts, the American Farmland Trust argues for more “efficient” (i.e. denser) urbanization and claims that, “One-sixth…” (17%) “… of the land urbanized since the Gold Rush … has been developed since 1990.” That might be an impressive figure, if it were not that the state has added 7 million urban residents since 1990, which is one-fourth (25%) of all the urban population added since the Gold Rush and equal to the 1990 population of New York City.

It is worth noting that California has agricultural preservation measures already in place for farm owners and, finally, that no one can compel an unwilling farm owner to sell their land to a developer or anyone else (except perhaps a government agency through eminent domain).

In California, as elsewhere in the nation, urbanization has not been the principal cause of farm land reduction. According to the US Census of Agriculture, farmland declined in California from 2002 to 2007 by 2.2 million acres. That 5 year reduction in farmland is approximately equal to the expansion of all California urban areas over the 50 years between 1950 and 2000.

Most Development is Not Urban

In the same document, the American Farmland Trust indicates support for the radical urban land regulations. Policies such as in Sacramento’s Blueprint that raise significantly inflate the price of land, make housing less affordable. The agricultural, property and urban planning interests who would ration land for people and their houses have missed a larger targets such as ultra-low density “ranchettes” favored by a small wealthy minority who live in the country, but are not farmers.

According to the US Department of Agriculture, rural, large lot residential development (non-agricultural) covered 40% more land than all of the nation’s urbanization in 2000. These parcels represent “scattered single houses on large parcels, often 10 or more acres in size.” Further, since 1980, the increase in this rural residential development has been one-third greater than the land area occupied by all of the urban areas in the nation with more than 1,000,000 population.

Finally, if there is a serious threat to agriculture, it is from over-zealous regulation that has put farmers at risk. Water reductions in the San Joaquin Valley – mostly the result of environmental demands – likely have taken more land out of production than any sprawl-happy developer.

Declining Human Footprint: An International Phenomenon

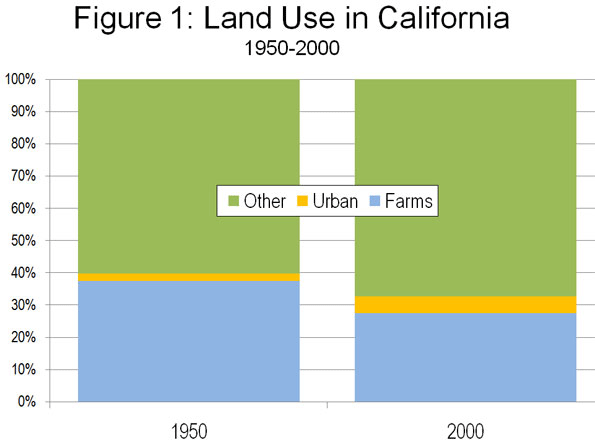

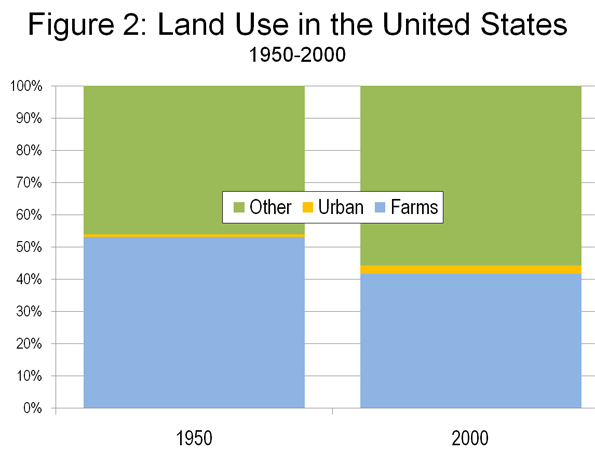

The human footprint, as measured by the total urban and agricultural land has been declining for decades, both in the nation and California, where the greatest growth has occurred (Figure 1 & 2). The same is also true of Europe (EU-15), Canada and Australia, where all of the urbanization since the beginning of time does not equal the agricultural land recently taken out of production. Even in Japan, the human footprint has been reduced. It may be surprising, but human habitation and food production has returned considerable amounts of land to a more natural state in recent decades, while America’s urban areas were welcoming 99% of all growth since 1950.

Note 1: This assumption represents the worst case, since not all land on which new urbanization was developed had previously been farmed.

Note 2: State data is available only between 1960 and 2004.

Photograph: Metropolitan Chicago, 2007 (Grundy County)

Wendell Cox is a Visiting Professor, Conservatoire National des Arts et Metiers, Paris. He was born in Los Angeles and was appointed to three terms on the Los Angeles County Transportation Commission by Mayor Tom Bradley. He is the author of “War on the Dream: How Anti-Sprawl Policy Threatens the Quality of Life.”