Canada is the largest high-income nation in the world without a comprehensive national freeway (autobahn, expressway or autoroute) system. Motorways are entirely grade separated roadways (no cross traffic), with four or more lanes (two or more in each direction) allowing travel that is unimpeded by traffic signals or stop signs.

The Economic Advantages of Motorways: Motorways have been associated with positive economic and safety impacts. For example, a synthesis of research by the American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials (AASHTO) noted the positive impact of US motorway system:

The Interstate Highway System represented an investment in a new, higher speed, safer, lower cost per mile technology which fundamentally altered relationships between time, cost, and space in a manner which allowed new economic opportunities to emerge that would never have emerged under previous technologies.

In particular, the AASHTO synthesis indicated that motorway

…investments have lowered production and distribution costs in virtually every industry sector.

It is a well known fact that motorways are by far the safest roads. We estimated that 187,000 fatalities had been averted due to the transfer of traffic from other roads to motorways between 1956 and 1996.

A World of Motorways: Truckers in Japan, Europe (the EU-15) and the United States can travel between virtually all major metropolitan areas on high quality motorways.

Further, motorway systems have and are being built in developing nations. By far the most impressive is China, which now has approximately 65,000 kilometers of motorway, not including motorways administered at the municipal level (as in Shanghai and Beijing). Only the United States has more, at approximately 85,000 kilometers. China’s plans call for the US figure to be exceeded within a decade. These roads are being built not only throughout populous eastern and central China, but also to the Pamirs at the Kazakh border and to Lhasa, in Tibet, across some of the most desolate and sparsely populated territory in the world. Mexico, a partner with Canada and the United States in the North American Free Trade Agreement also has an extensive motorway system.

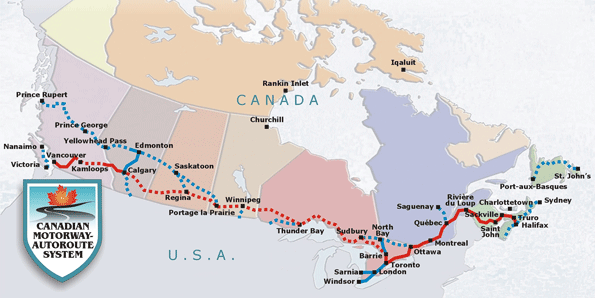

Motorways in Canada: Canada, however, is an exception. Only a quarter of metropolitan areas are connected to one another by motorways. Edmonton and Calgary are among the few metropolitan areas in the developed world that are not connected to comprehensive motorway systems (Vancouver is connected to the US system, but not to the rest of Canada).

For many trips between Canadian metropolitan areas, it takes less time to travel through the United States on its motorways than on the Canadian roads (such as between Winnipeg or Calgary and Toronto). The principal problem is the long, crowded, slow, two-lane stretch of roadway through the northern Great Lakes region between the Manitoba-Ontario border and between Sudbury and Parry Sound. There is also a long section of roadway in the British Columbia interior that a Calgary talk show host referred to as a “stagecoach” trail. Canada pays an economic price for this lack of a world-class highway system, both in terms of manufacturing and tourism.

However, parts of Canada are well served by motorways. Much of central and eastern Canada is connected by motorways, with routes from Windsor, Ontario, through Toronto, Ottawa, Montreal, Quebec to Halifax. This route includes only a short segment that is not motorway standard in the province of Quebec as it approaches the New Brunswick border.

Moreover, despite its reputation to the contrary, the largest Canadian urban areas have world class freeway systems. Few, if any, urban areas in the United States or the developed world have more kilometers of motorway or motorway lanes in relation to their urban area size as Toronto and Montreal.

A Canadian Autobahn: In cooperation with the Frontier Centre for Public Policy, we proposed a world class highway system for Canada. In a report entitled “A Canadian Autobahn: Creating a World Class Highway System for the Nation” we proposed:

- Upgrading the entire transcontinental route from Halifax, through Toronto to Vancouver to motorway standards. These improvements should be completed within 10 years and would cost approximately $28 billion (2009$).

- Upgrading other principal routes to at least pre-motorway standard, which would require “twinning” (four-lanes) and minimizing the number of grade crossings. The longest of these additional highways is the Yellowhead route: Edmonton and Calgary to the Canada-U.S. border; Ottawa to Sudbury; and across the island of Newfoundland. These improvements should be completed within 15 years and would cost approximately $33.5 billion).

The transcontinental route would provide a long overdue economic stimulus to urban areas such as Thunder Bay and Sault Ste. Marie. The improved Yellowhead route would provide far better access to the new deepwater, superport at Prince Rupert (British Columbia), which is the closest North American port with connections to major Asian markets. This could materially improve Prince Rupert’s competitiveness relative to larger ports on the US West Coast, such as Los Angeles and Long Beach (which have become much less competitive themselves in the last decade). The improved roadway would make it possible to effectively serve the markets of the US Midwest, South and East through a connection to I-29 in North Dakota.

The report was unveiled at a Calgary event on October 29 and was covered by media across the nation.

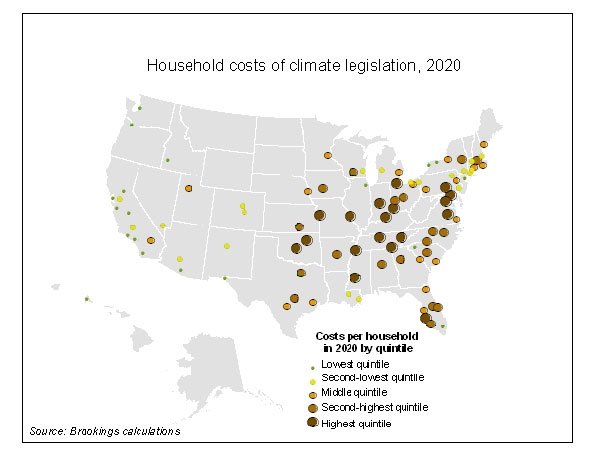

What About Greenhouse Gas Emissions: A question was raised about the advisability of expanding highways at a time that the world is attempting to reduce greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. Such a strategy would seem to be at odds with the popular perception that we shall all have to abandon our cars and move into flats in the central city. This perception presumes that people are prepared to return to the standards of living and lifestyles of 1980, 1950 or even 1750. In all of my presentations on similar issues I am yet to uncover any groundswell of support for the lifestyles of yesterday.

It needs to be recognized that the international commitment to reducing GHGs is based upon an assumption of minimal impact on the economy. GHG reductions will be achieved only if they are acceptable to people, which requires acceptable costs (research by the United Nations International Panel on Climate Change suggests an upper bound of $50 per ton). Cost effectiveness is necessary to not only prevent a huge increase in poverty, but also to allow continued progress toward poverty alleviation and upward mobility. In fact, as recent US research indicates, there is scant real world potential to reduce GHGs from reduced levels of driving.

Given the strong association between economic growth and personal mobility, there is a single realistic path to substantial GHG emission reduction: better technology. Fortunately, developments suggest that technology is, indeed, the answer.

The question, thus, comes down to whether jobs in the northern Great Lakes region (and elsewhere) are more important than strategies that are politically correct, but comparatively ineffectual with respect to materially reducing GHG emissions. It seems likely that people will place a priority on jobs.

Finance: Because of the importance of tying the nation together, it would be appropriate to spend federal and provincial funds on the Canadian Autobahn. User fees, such as a dedicated gasoline tax (as in the United States) or tolls (as in France, China and Mexico) could finance the expansions, using public-private partnerships or “arms-length” government corporations.

Wendell Cox is a Visiting Professor, Conservatoire National des Arts et Metiers, Paris. He was born in Los Angeles and was appointed to three terms on the Los Angeles County Transportation Commission by Mayor Tom Bradley. He is the author of “War on the Dream: How Anti-Sprawl Policy Threatens the Quality of Life.”