Germany likes to brag about its green credentials. It is a source of pride and it is justified to a certain extent. The country, which is located on the same latitude as Canada, had the largest number of installed solar panels as of 2007.

The key to growth clearly has not been abundant sunshine, but massive subsidies. Germany sponsors its solar industry with generous tax credits that take the form of feed-in tariffs, i.e. payment above the going market rate for energy from renewable sources like solar panels, it can run anywhere from twice to three times the market rate for a conventionally produced kilowatt. These tariffs can run high. They are being lowered slowly but perhaps a bit too slowly. As we have recently seen with the disasters impacting Spain’s renewable energy industry, dependence on subsidies can create a potential catastrophic downturn once the spigot is turned off.

Would a similar model be appropriate for sponsoring renewable energy in the US? Probably not, in large part the technology is already developed. The Germans and now the Chinese have already subsidized their industries. The legwork has been done and anti-greenhouse legislation will sustain the market without massive subsidization.

The first factor is that most of the investment in research and development has created the pre-conditions for grid parity within the next few years for southern countries. Even Germany will achieve it by 2012 according to the German business newspaper Handelsblatt. The economies of scale are sinking unit costs dramatically and production technologies like thin film are allowing solar cell manufacturers to produce ever more efficient panels with less and less silicon. Several silicon production plants are set to come on line in China soon.

The US, whose fiscal situation is parlous compared to China and even Germany, wants to waste years developing already available technologies from scratch. It could try the European approach but would probably be much better off to follow the same path that it followed with the automobile or the motion picture: allow other countries to get the basic technology in place and concentrate its exceptional energy on marketing and scaling up the technologies from abroad.

China’s entry into the market seems destined to create a dramatic collapse in the price of what was until a few years ago essentially a cost plus industry. China has low labor costs and inflation busting economies of scale. China’s entry into the silicon wafer market already has depressed prices for the once dear raw material. They are also working on a massive power plant with First Solar of the United States.

Some are predicting that China’s entry into the renewable energy market will have the same effect as its entry into the consumer electronics market, i.e. it will make the expensive affordable and then cheap. German solar cell production companies have suffered much like its chip producers but to the general benefit of the economy. China will drive production costs further down. Germany is still coming to terms with this.

A recent article in Die Zeit illustrates the growing discrepancy between renewable energy policy and the market potential. The feed-in tariffs have the perverse effect of making solar energy far more expensive than it actually needs to be. The government subsidies are essentially shielding domestic producers from China making the consumers pay the higher rates. Germany needs to focus on its traditional strengths in producing industrial machinery and carve a niche for itself. The US would be better off to maintain trade relations with China and let Adam Smith’s invisible hand work its magic. It would be far cheaper than trying to use protectionist measures to protect domestic manufacturers.

All this is predicated on the assumption that the price of oil will only increase in price in the coming decades as China and India motorize their masses. This in turn will drive up conventional power costs. Even at its current price of around $70 a barrel, oil is still 7 times more expensive than it was just a decade ago. Some are predicting that that last year’s prices of almost a $150 a barrel represent a taste of what will confront the world when the economy begins to grow again

This, however, will be a gradual process, based on undulating prices. The hysterical claims of Peak Oil have been delayed again and again by technological improvements. The latest finds off of Brazil and the Gulf of Mexico represent dramatic examples. Massive new gas reserves in North America represent another countervailing force. In the end, fossil fuels will be more expensive, but they will make renewable energy more competitive only at reasonable price points.

Politics will also play a role. Climate change and the perceived need to combat it has gained enormous currency among world leaders including German Chancellor Angela Merkel. Regardless of what one thinks of the arguments calling for action, we will probably see some sort of carbon tax in the future, whether it be cap and trade or some other means of increasing the costs of carbon emissions. Conventional fuels like coal, oil, and natural gas are only going to get more expensive for political if not economic reasons. The growing consensus, regardless of its veracity, is set to create huge costs for non-renewable sources of energy.

Over time, this will make renewable energy more attractive and unit costs will shrink as economies of scale start to kick in. The European cheerleaders of climate legislation are not doing it out of the goodness of their heart. They want to see a return on the billions spent on developing renewable technology. The US would be ill-advised to simply try to create technologies that are already up and running. Take the technology, commercialize it and thank the Europeans for footing the bill.

The US would be well advised to keep their renewable energy markets open. The Europeans will come and are coming. The solar energy trade fairs in Germany focus on the immense potential available in the US market. Several large German producers are expanding aggressively on the American market bringing with them the technologies that they have created. China will also start to flood the market with cheap silicon wafers and further reduce solar panel costs. The US does not need to subsidize this technology lavishly. It simply needs to allow the companies that have it to sell it on their market. The initial support provided by countries like Germany was more than enough to get the technology to the point where it is ready to survive on the free market.

Kirk Rogers resides in Bubenreuth on the outer edges of Nuremberg and teaches languages and Amercan culture at the University of Erlangen-Nuremberg’s Institut für Fremdsprachen und Auslandskunde. He has been living in Germany for about ten years now due to an inexplicable fascination with German culture.

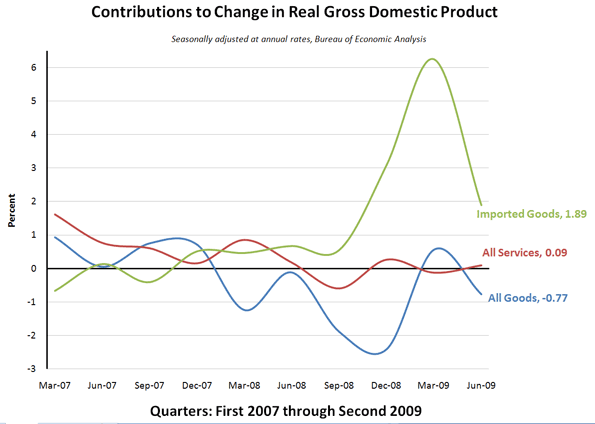

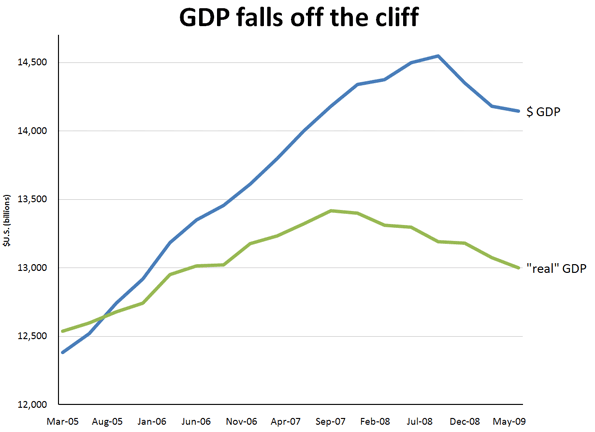

Data from Bureau of Economic Analysis; author’s calculations

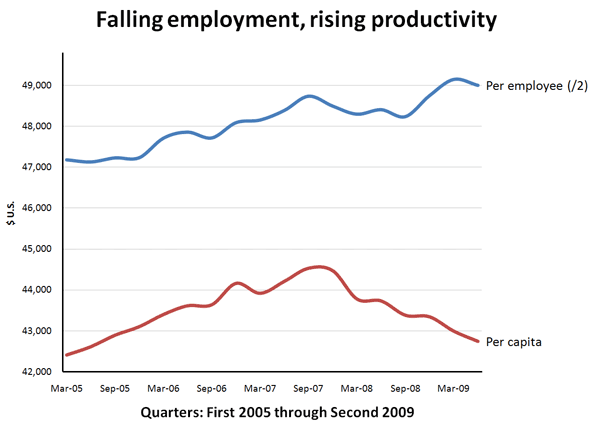

Data from Bureau of Economic Analysis; author’s calculations Data from Bureau of Economic Analysis and Census Bureau. Per employee divided by 2 for scale.

Data from Bureau of Economic Analysis and Census Bureau. Per employee divided by 2 for scale.