Nobel Prize-winning economist Paul Krugman was quoted widely for saying that the official recession will end this summer. Before you get overly excited, keep in mind that the recession he’s calling the end of started officially in December 2007. Now ask yourself this: when did you notice that the economy was in recession? Six months after it started? One year? Most people didn’t even realize the financial markets were in crisis until the value of their 401k crashed in September 2008. Count the number of months from December 2007 until you realized the economy was in recession, add that to September 2009 and you’ll have an idea of when you should expect to actually see improvements in the economy.

Douglas Elmendorf, Director of the Congressional Budget Office (CBO), testified on “The State of the Economy” before the House Committee on the Budget U.S. House of Representatives at the end of May. CBO sees several years before unemployment falls back to around 5 percent, after climbing to about 10 percent later this year. Remember this phrase: Jobless Recovery; it happens every time we have a recession. Employment historically does not increase until 6 to 12 months AFTER GDP starts to improve. Even Krugman admits that unemployment will keep going up for “a long time” after the recession officially ends.

While some of us are worrying about stagflation – a stagnant economy with rising prices – the CBO report does a good job of describing why deflation is worse than inflation. Deflation would slow the recovery by causing consumers to put off spending in expectation of lower prices in the future. The risk associated with high inflation is primarily that the Federal Reserve would raise interest rates too fast, stalling the economy – similar to what Greenspan did to prolong the recession in the early 1990s. We think the real conundrum is this: how do you deal with an asset bubble without deflating prices? Preventing deflation now simply passes the bubble on to some other asset class at some future time.

CBO calculates that output in the U.S. is $1 trillion below potential, a shortfall that won’t be corrected until at least 2013. New GDP forecasts are coming in August from CBO. They say the August forecast will likely paint an even gloomier picture than this already gloomy report. Hard to imagine!

There are plenty of reasons that Krugman and others are seeing encouraging signs in the economy. Social Security recipients received a large cost-of-living adjustment, payroll taxes were lowered so that employees are taking home bigger paychecks, larger tax refunds, lower energy prices – all of these lead to an uptick in consumer spending in the first quarter of 2009. I checked in with Omaha-area Realtor Rod Sadofsky last week. He has seen an improvement in sales in the range of median-priced homes which he attributes to the $8,000 tax credit available to first-time homebuyers (or those who have not owned for at least three years). Along with an up-tick in that segment of the market, those sellers are able to move up to higher priced homes a little further up the range, further improving home sales. However, the tax incentive is scheduled to expire at the end of 2009. When the stimulus winds down…well, there will be no more up-ticks. CBO agrees with Rod and warns of a possible re-slump in 2010 when the effects of the stimulus money begin to wane.

CBO’s Dr. Elmendorf has a way to solve this problem: to keep up consumer spending, he suggests that people should work more hours and make more money. Duh! We think we hear Harvard calling – they want their PhD back! CBO seems undecided about which came first in the credit markets: problems in supply or problems in demand?

“Growth in lending has certainly been weak, but a large part of the contraction probably is due to the effect of the recession on the demand for credit, not to the problems experienced by financial institutions.”

“Indeed, economic recovery may be necessary for the full recovery of the financial system, rather than the other way around.”

We shouldn’t be so hard on Elmendorf. The report makes it clear just how difficult it has been to figure out 1) what happened 2) why it happened 3) what do we do about it and 4) what happens next. CBO seems to be reaching for answers while to us it is obvious they are missing the point by not even considering that manipulation has wrecked havoc on the markets. Whenever things don’t make sense to someone like the Director of the CBO, experience tells us there’s a rat somewhere.

Regardless of how overly-complicated financial products may become, the economy really shouldn’t be that hard to figure out. Still, no one seems to know how far down the banks can go – if banks don’t lend to businesses, businesses close, people lose their jobs, unemployed people default on loans, banks have less to lend, and banks can’t lend to businesses…Seems we are damned if we do and damned if we don’t: too much borrowing caused the crisis; too little spending worsens it. Do they want us to keep spending money we don’t have?

While Krugman is admitting that the world economy will “stay depressed for an extended period” CBO is reporting that “in China, South Korea, and India, manufacturing activity has expanded in recent months.” The other members of the G8, however, aren’t faring any better than we are: GDP is down 10.4 percent in the European Union, 7.4 percent in the UK and 15.2 percent in Japan. Canada – whose banks are doing just fine without a bailout, thank you very much – saw GDP decline by just 3.4 percent in the last quarter of 2008.

Undaunted by nearly 10 percent unemployment – after predicting it would rise no higher than 8 percent – President Obama announced today that the White House opened a website for Americans to submit their photos and stories about how the stimulus spending is helping them. If they can’t manage the economy, they can still try to manage our expectations about the economy.

Susanne Trimbath, Ph.D. is CEO and Chief Economist of STP Advisory Services. Her training in finance and economics began with editing briefing documents for the Economic Research Department of the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco. She worked in operations at depository trust and clearing corporations in San Francisco and New York, including Depository Trust Company, a subsidiary of DTCC; formerly, she was a Senior Research Economist studying capital markets at the Milken Institute. Her PhD in economics is from New York University. In addition to teaching economics and finance at New York University and University of Southern California (Marshall School of Business), Trimbath is co-author of Beyond Junk Bonds: Expanding High Yield Markets.

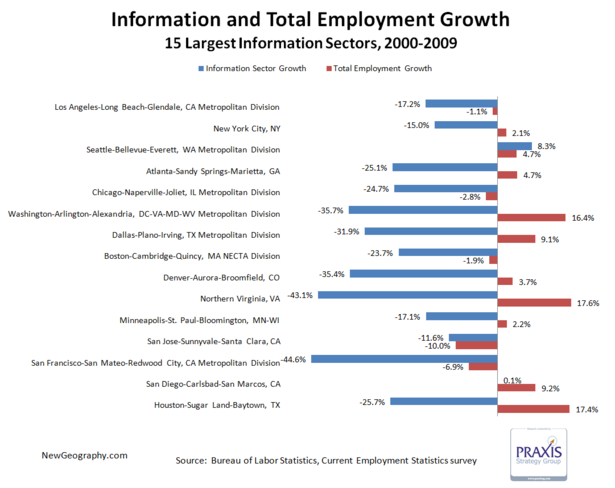

Using employment growth rates as the measurement criteria:

Using employment growth rates as the measurement criteria: