Last month I bought an old fixer-upper for $15,000 in Cincinnati. It was originally offered at $17,000, but I got the sellers down a bit. The place is a complete disaster. All the copper pipes and wires have been stripped out of the building. It hasn’t seen paint for decades. Every window and door needs to be replaced. The roof is shot. There’s no insulation of any kind. The yard is a mess. And there are plenty of similar houses in the neighborhood. So why exactly did I buy it? I’ll get to that in a minute.

But first I want to relate a conversation I had with a contractor this morning. He’s an older man who lives in the distant suburbs and has very definite opinions about the city. He spoke to me in a kindly grandfather voice. “Do you understand where this house is? Do you know what kind of people live there?” He used some colorful language which I won’t repeat. Let’s just say he’s a white guy of a particular generation from the South… He advised me to take the money I’m about to spend renovating the house and use it to buy a nice big new home on a good sized piece of land across the river in Kentucky instead.

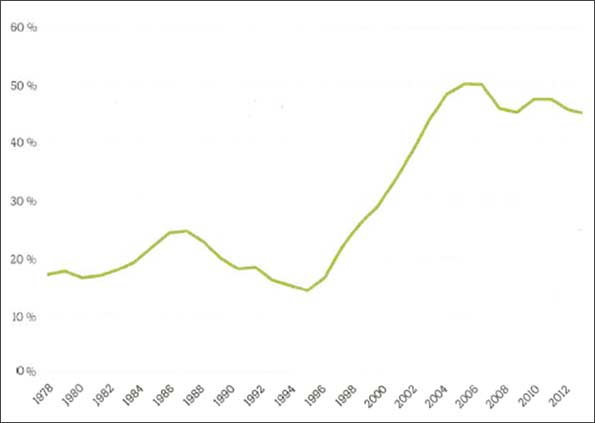

If this were 1980, or 1990, or 2000 this man’s recommendation would have been entirely valid from an economic perspective. Inner city neighborhoods all over the country were hemorrhaging population, jobs, and revenue for decades. It would have been a disastrous investment. But times have changed. Not everyone has noticed.

Here are some before and after photos of buildings in the immediate neighborhood curtesy of Google Street View. Since the Google van has driven by a few times in the last decade it’s possible to see the same buildings from the perspective of different years. People have consistently been buying up cheap run down properties, fixing them up, and incrementally improving the neighborhood. This is no longer a place of permanent decline and disinvestment. The area hit bottom a few years back and it’s already on the way back up. It’s not entirely there yet, but it’s well on its way.

In addition to recently renovated older buildings, vacant lots are sprouting quality new construction. These two homes are LEED certified for energy efficiency.

gantrylife.com / bayerbecker.com

gantrylife.com / bayerbecker.com

A few blocks away a larger vacant parcel is currently being redeveloped into a market rate multi-million dollar mixed use building by an out-of-state firm. I’ve noticed that local companies don’t always appreciate their own assets, but plenty of well funded ventures from other metro areas are taking advantage of the opportunities on offer in Cincinnati.

Right next door is the American Can Lofts building which was completely transformed in 2011 after siting empty since 1978. I arrived in Cincinnati for the first time a few years ago just as this building was having its grand reopened. That takes me to how a guy from San Francisco ended up looking at property in Cincinnati in the first place. Which takes me to why I think Cincinnati is such a great investment.

I have long time friends-of-the-family in Los Angeles. Their daughter graduated from university, got married, and promptly left California. She and her husband explored the country looking for a place to live that they both liked and could afford. (That ruled out nearly every inch of California.) They lived in Baltimore, Maryland for a while and then Portland, Oregon for a year before moving to Cincinnati. They could afford Baltimore and appreciated its gritty charm. But they really loved Portland – give or take the ridiculously high rent and real estate values. What they wanted was Portland at a Baltimore price.

And then they moved to Cincinnati. Ahhhhhh. They bought a charming century old four bedroom house in perfectly good condition for $50,000. It was the best thing any young couple could have done, both financially and in terms of their quality of life. If they had stayed in Los Angeles or Portland they would still be renting (with room mates) and just scraping by. In Cincinnati they became comfortably middle class home owners at the tender age of twenty five. Their mortgage is $400 a month. And they’ve had no trouble finding good work or like minded friends. They aren’t the only young people making this kind of move. Which is probably why out-of-state developers are investing in the city.

The odd thing about Cincinnati is that while the existing housing stock is very reasonably priced, good quality space is commanding fairly high rents. Apartments in the America Can building go for $610 for a one bedroom up to $1,480 for a three bedroom – and there’s a waiting lists. My inner capitalist sees a generous spread between affordable property and the potential for solid rent from solvent tenants. If I can provide a high quality building I believe I can find good people to occupy the space at a rent that’s reasonable for them and profitable for me. And I can do it without taking on debt and without being a slumlord. Try that in San Francisco and see how far you get…

I just hired a young local architect to help with the reconstruction. This is going to be a fun little adventure. And I’m really happy that old guy who was trying to give me advice lives in the distant suburbs. He’d be a terrible neighbor.

John Sanphillippo lives in San Francisco and blogs about urbanism, adaptation, and resilience at granolashotgun.com. He’s a member of the Congress for New Urbanism, films videos for faircompanies.com, and is a regular contributor to Strongtowns.org. He earns his living by buying, renovating, and renting undervalued properties in places that have good long term prospects. He is a graduate of Rutgers University.